Hi All

If one reduces the beshir motif to

red curves + red dots, then there might be some funny speculative

connections in the following.

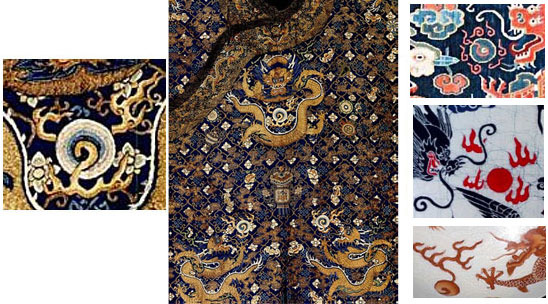

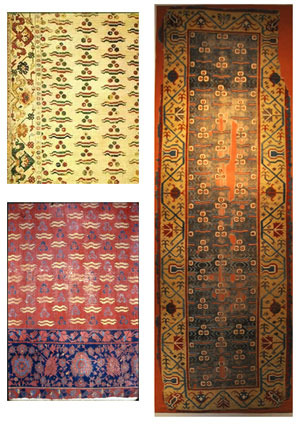

The Ottoman tulip on the kaftan I

posted earlier is designwise related to the very interesting "Cintamani"

pattern.

cintamani. kaftan detail

cintamani. kaftan detail

The cintamani is in

itself an enigmatic motif which surely has travelled along the silk road.

The origin of the cintamani motif is complex - and probably in itself of

course multi sourced.

This motif was by the Ottomans called

cintamani which is Sanskrit suggesting a direct connection to India and

tibetan/chinese Buddhist tradition and iconography,

From wikipedia:

"a wish-fulfilling jewel within both Hindu and Buddhist

traditions.....In Buddhism it is held by the bodhisattvas, Avalokiteshvara

and Ksitigarbha. It is also seen carried upon the back of the Lung ta

(wind horse) which is depicted on Tibetan prayer flags. In Tibetan

Buddhist tradition the Chintamani is sometimes depicted as a luminous

pearl and is in the possession of several of different forms of the

Buddha.

Within Hinduism it is connected with the gods, Vishnu and

Ganesha. In Hindu tradition it is often depicted as a fabulous jewel in

the possession of the Naga king or as on the forehead of the Makara." (Naga is a multi-headed snake, Makara a composite of elephant,

crocodile and sometimes peacock-tail, also known in China)

The

circles are the jewel(s) or pearl(s). The number of 3 jewels is Buddhist

tradition (triratna). The curves I have seen interpreted as Buddha's lips,

which I somehow find bit unlikely. Flames or flaming cloud bands seems

more appropriate, probably depicting glowing holiness:

Triratna

TriratnaI am not quite sure but these Afghan

Buddhist stone carvings are also said to represent the cintamani: The

curves here doesn't look like flames, perhaps rather waves, which of

course also makes sense as pearls and ocean, and is also in accordance

Buddhist religious concepts:

Footprint of Buddha + Triratna. 1st century,

Gandhara

Footprint of Buddha + Triratna. 1st century,

GandharaThe Tibetan wind horse, carrying the flaming

cintamani. In the corners, representing the corners of the world we have

traditionally the peacock, the dragon, the lion, the tiger:

The flaming

pearl seems to generally be an attribute of Chinese / Tibetan dragons. In

following 19th Chinese robe the central dragon is accompanied by Buddhist

emblems, in the center the flaming pearl (and the dragon itself almost an

flaming cloud band):

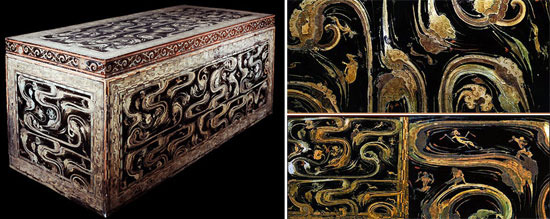

The dragon motifs from

Mawangdui, Lady Dais coffins and the silk banner depicts complex

mythological and cosmological material, where the relation between cloud

band and dragons play a prominent role - and the visual articulation of

the sun as a red circle + the red circular dots around the right dragon is

striking:

Painted silk

banner. Mawangdui (c. 168 BC)

Painted silk

banner. Mawangdui (c. 168 BC) The coffin of

Lady Dai. Mawangdui (c. 168 BC)

The coffin of

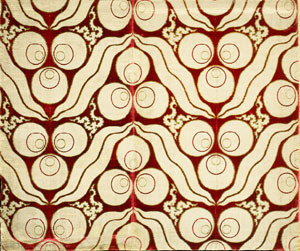

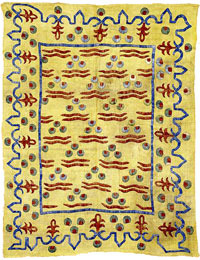

Lady Dai. Mawangdui (c. 168 BC)The David Collection in

Copenhagen (which by the way holds the finest collection of Islamic art in

Scandinavia

http://www.davidmus.dk/en ) has this Ottoman velvet with

the cintamani motif:

I quote

from their description:

"The chintamani pattern is most often

associated with the art of the Ottoman Empire, but it is older and

probably originated with the Central Asian Turkic peoples. It has been

convincingly interpreted as a combination of the tiger’s stripes and the

leopard’s spots, and as such refers especially to manly

courage."Would be interesting to see the source for this

interpretation, but I suppose its obvious that leopard and tiger skins

must have had extremely high prestigious and symbolic value in Turkic

nomadic culture:

Ceremonial yurt with

leopard skins, mongolia

Ceremonial yurt with

leopard skins, mongoliaHere we have a dotted lion and a

striped tiger - both apparently desperately fighting cloud bands:

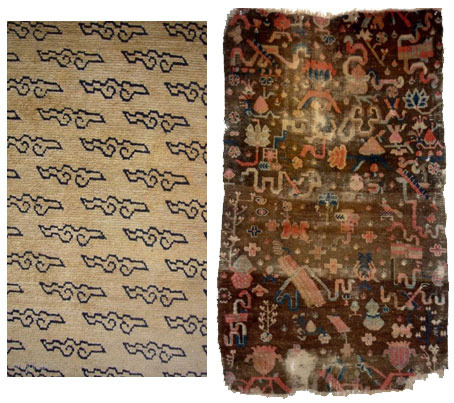

I haven't

really found any textiles or chinese/mongolian images where i definitively

could say it were leopards (The lion above is the closest I can get),

Tigers are a bit easier, and we have the Tibetan tiger rugs. Even though

most Tibetan tiger rugs aren't very old (the oldest existing perhaps

19th?) they seem to represent a very old tradition as ceremonial gifts to

Lamas:

The

tiger stripes above seems very directly related to the cintamani. And

interesting to se that tiger stripes and cloud bands in Tibet can turn out

very much alike. And the same goes for dragons and cloud bands:

And then back to

the Anatolian rugs where the cintamani also is a main field pattern, here

even with cloud band and tulip borders

:

And surely this pattern and

layout travels back the silk road, here ending up upon an Uzbek

embroidery:

The cintamani is also a

very important and almost one of the emblematic ornaments of ottoman Iznik

tiles and ceramics. It is fascinating to see this motif used and

transformed in the limited colour scheme of ottoman ceramics, where of

course the red colour is very important:

The

cintamani motif certainly gets used as a floral pattern (also intertwined

with the tulips).

But it seems like

its origin in pearls and clouds is parallel alive for the ottomans. In the

tall vase we see the cintamani pearls transformed into sails on ships (and

perhaps the cloud band into red waves). At the last plate (probably not

very old) we se the pearls in the sea:

Actually

it would be rather strange if the ottomans didn't have some kind of

concepts regarding "meaning" of a pattern with such a strong visual

impact, especially if worn by Sultan and court. Even if they had adapted

the pattern without knowing anything of its original symbolic content, I

would think they would have had to invent some kind of explanatory notions

around it.

Another motif connected to the cintamani - perhaps

symbolic inherent, perhaps invented by the ottomans - is its connection to

the peacock:

The

gigantic byzantine columns, which original probably have been brightly

coloured, must have been impressive when the ottomans conquered Byzans.

With the right colours they must have looked very much like the peacock

feathers. They could have played a role in how and why the cintamanti

became an emblematic motif in Istanbul:

But anyway the cintamani pearls

are visually easily transfigured into the eye on the peacock's feather.

And that's rather fascinating: if the cloud band represent the dragon and

the pearls the peacock, then the ottoman cintamani can be seen as a hyper

stylized version of the ancient conjunction of phoenix and dragon. The two

mythological figures representing either astrological constellations, the

sun and the moon, or the male and female as in taoist yin and

yang:

This connection

is of course speculative. But even if the cintamani were just a beautiful

decorative pattern for the ottomans, then I still find it fascinating as

an example on how symbolic iconography surely have migrated through asia,

perhaps as abstract intermingled echoes - all the way from ancient China

to ottoman Anatolia. Be it phoenix and dragon, tiger and leopard or Buddah

and pearls.

And of course the town Beshir / Bashir and the Amu

Darya is geographically placed literally in the middle of this, right on

the Silk Road routes.