I thought Turkotek readers might be interested

to see some example of the actual goddess figures excavated at Çatalhöyük

and Hacilar:

http://picasaweb.google.com/hughrance/CatalhoyukHacilar

Many people have chipped in to the debate on Mellaart and his

discredited account of connections between wall paintings he claimed to

have seen (but not photographically recorded) from Çatalhöyük with motifs

in Anatolian kilims. My memory from the time and from recollections of

discussions with Max Mallowan was that Mellaart became a persona non grata

and excavations were stopped by the Turkish government because of

accusations of misappropriation of archaeological finds. However, the

excavations themselves have left a remarkable legacy and record of what

was possibly the first settled agrarian Neolithic civilisation in

Europe.

Clearly there was an ancient tradition of producing mother

goddess figurines in the region in the Neolithic era and of placing them

in niches along with other figurines such as bull heads for ritual or

religious (in the wider sense) purposes. This tradition was by no means

confined to Anatolia and a more ancient tradition goes back at least to

the Paleolithic era and direct comparisons can be made with figurines from

other parts of Europe, the Middle East and Indian subcontinent. One

interesting aspect of a more recent find from the current series of

excavations (see the latter photos in my link above) is the discovery of a

“goddess” figurine which exhibits features of both pregnancy/fertility and

perhaps death through the depictions of emaciated limbs and skeletal

protrusion. There are also parallels here with figurines from other

cultures.

Personally I have not be influenced in any way by

Mellaarts reports, contrary to the unfounded assertion by Steve in his

post following my last contribution. I have however taken the time to read

his excavation reports and study some the actual finds made, along with

other earlier Paleolithic figurines in the British Museum, thanks to being

in the right place at the right time while studying at University College

London in London in the 1970s and 80s. I have however been influenced in

my own work and my understanding of ancient cultures by the remarkable

finds he and others have made, particularly the sculptures. Incidentally,

most of the Neolithic female figurines from Anatolia exhibit a hands on

breasts posture although a few do show a hands on hips or thighs posture.

Whatever one wants to make of them and however one might interpret them,

they are remarkable figures in their own right.

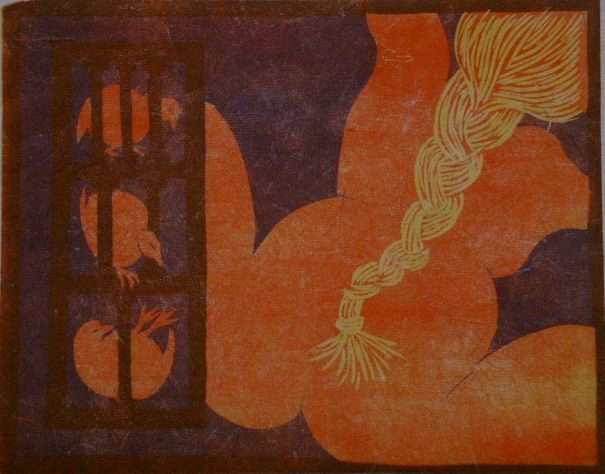

To give a little

more insight into how the creative process works, here is a woodcut I made

having studied one of the figurines from Çatalhöyük. The point of sharing

this image is to show how an artist may be inspired by and copy or borrow

from other work, but at the same time give birth to a new element which

may contribute a different perspective on even a fresh insight into the

original. I am not making any claims for my own woodcut and this isn’t

about the merits or otherwise of the image, I am trying to explain the

process. So, having taken one of the Çatalhöyük figurines as a starting

point other elements added themselves. There was no conscious intention in

producing the I II III cage-like structure with birds, nor any conscious

intention to depict the birds in any particular way. Indeed, at the time I

had no idea these images would even become birds.

So, having

started with the bare idea of the female form and having cut the woodblock

quite spontaneously without any predetermined outcome, it presented itself

with what now appear to be symbolic birds tied into a numeric cage. What

does this mean? On one hand it is just a picture or illustration, on the

other it appears to have a meaning. Who is to say exactly what that is.

One may speculate about sexuality, fertility, childbirth, time, death,

etc. all of which might be construed from an intellectual analysis of the

combined elements in the woodcut. One might also just enjoy it and if

consider whether an image we look at has its own way of communicating with

us subliminally, bypassing the often rigid intellectual and judgmental

filters that we impose on our consciousness. If we are open to the

possibility that meaningful images might affect us then this becomes a

possibility. If we are closed to the possibility, then clearly this can

never happen.

As the Chinese Zen Master Rinzai said:

“When

you meet a master swordsman,

show him your sword.

When you meet a

man who is not a poet,

do not show him your poem.”

Perhaps I

should have taken his advice?

P.s. Thank you Yaser Al

Saghrjie for your attribution of the origin of my kilim that started off

this thread.

p.p.s. Anyone interested in reading an in depth study

of how motifs have developed over the millennia in different tribal

cultures would be interested to look up the life work of Carl Schuster:

http://www.tribalarts.com/people/schuster.htmlHis

work "Social Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art, a record of tradition

and continuity" was published in 12 volumes by the Rock Foundation in 1988

and I was very lucky to find a set a few years ago in an NY bookshop. It

is available in some university libraies and a few public libraries but is

available in an abridged one volume edition "Patterns That Connect: Social

Symbolism in Ancient & Tribal Art." (1996) published by Harry N.

Abrams.