Dear Joel and all,

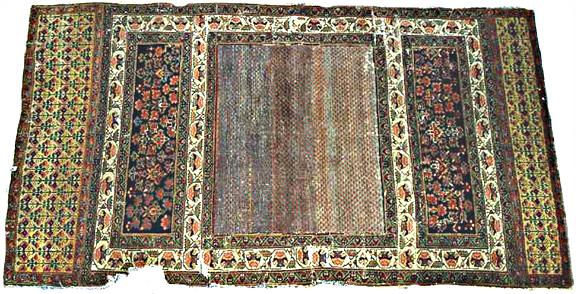

Here are a few

supplemental images. The first shows the stripes in the ACOR example,

which the owner brought to the session after long, long exchanges with me

as to its use. The stripes remind me of the backs or bottoms of certain

bags, areas generally not seen.

Next is an image

of how the owner displays it., simulating what it might have looked like

on a horse. I cannot speculate how the pieces were used in relation to the

saddle.

This is an image of the back, quite similar to

Joel’s.

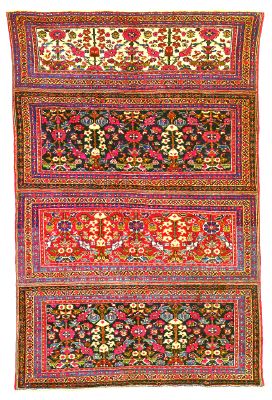

Next is an image (from a German auction long ago) of two

pieces that were cataloged as being part of a Senneh saddle set. They’re

differently shaped than the ones brought to the ACOR mystery rug section,

but may have served a similar purpose.

Now, some final

comments. First, it should not surprise anyone that there are paneled pile

weavings that serve a variety of functions but are clearly not composites.

Here is a box cover that I showed on Turkotek a long time ago and has been

referred to several times and then one posted to Turkotek by Stephen Louw.

These box covers are not well represented, if at all, in the

literature.

In addition, Turkotek has seen many, many discussions of

bags with panels. The ACOR set is as woven and Joel’s piece seems to be as

well.

I don’t feel that the word “faux” is at all applicable and,

Joel, I don’t think that you should feel that you have “a non-functional

copy of a bygone era saddle-set”. Horse covers and saddle sets were still

used in Persia in 1925 (when these may have been, +/- a few years). Cotton

was the foundation of choice for the exquisite horse covers and saddle

rugs of Senneh, Ferahan and Bijar. For long term function, felt next to

the horse might be preferred, but many of these sets saw limited use in

ceremonies and then were displayed in the homes.

Last, the size is

certainly not too large for a horse. It may be a few inches longer than

the average horse cover from nape to rump, but it’s not oversized for that

function.

We all have to realize that we there are still

discoveries to be made. I don’t know how one could find in the literature

a set similar to those being discussed here, but I’m sure they still exist

in Iran and maybe are still being used.

Wendel