Posted by Jim Allen on 01-23-2008 11:18 AM:

The Tekke Experience

The following is a small part of a new paper I am working on. I think it is

appropriate to bring up a few possibly new issues so I can attempt to answer the

question asked about the "high points" of Tekke aesthetic achievement.

After obtaining their annual supply of the best wool dyed with the

richest colors the Turkomen would weave sumptuous carpets and utilitarian

objects for their own use and for trade. O’Donovan went into this aspect of

their economic existence at length. They needed pots and pans, salt, rifles, and

a few other “necessities” to make their lives more comfortable. What does being

a rich Khan mean if it doesn’t mean being more comfortable than others who are

less well off?

It goes without saying that almost every weaving created

by the Turkoman people was for sale, at one time or another, depending on the

vicissitudes of nature and their own productivity. Perhaps the question of

whether or not all Turkoman weaving’s were created for trade or sale should be

addressed here.

First let’s consider the difference between those

objects woven for trade versus items made for sale. This difference basically

depended on who their trading partner was. For instance, salt was traded between

Turkoman tribes and perhaps the medium of these exchanges was wool, dyed or not.

It is my opinion that even small lots of the most vivid and colorfully dyed wool

was highly valued by the various tribes as it was used as a special decoration

in dowry weaving's.

Many if us have noticed very small amounts of lac

dyed wool or silk in very old Yomud weavings. I propose that small lots of lac

dyed wool or silk were obtained through trade between the Salor and Yomud tribes

in the early 18th century. This would have occurred before the Yomud defeated

the Salor and the Tekke around 1750 AD at Khiva.

Nomadic societies all

over the planet trade salt for value added objects or materials. This occurs in

the Bolivian highlands as well as in the para Caspian Sea regions. Lac was by

far the most expensive dye stuff on Earth in the 18th century. Nobody knows for

sure why the Salor were the main purveyors of lac dyed wool and silk in central

Asia but their weaving's show by far the greatest amount of this dye stuff.

I doubt seriously that fine pile technique Turkoman rugs were ever used

strictly as utilitarian objects. I believe this because their potential value in

trade was too great. The only exceptions would have been those culturally

important icons of power and prestige, and even those objects must have been

considered as trade material in the worst of times. I suppose that the usual

floor coverings in any Turkoman yurt would have been felt, the same material

that covered their yurts. If a pile technique carpet was used in the yurt I am

sure it was placed on top of a felt “pad”.

In all likelihood the only

Turkoman pile technique woven artifacts made strictly for personal use were

their small utilitarian dowry objects such as Ok Bosh, torbas, mafrash, spindle

bags, etc. I suppose the line between tradeable and untradeable artifacts was

drawn according to their relative value. For instance, what value would a

Turkoman torba have had to merchants in Meshad or Bukkara in the early 19th

century? I am sure they had insufficient value to justify their use in any sort

of trade or exchange for “city goods”.

Rugs of any size would have had

utilitarian value to civilized people so these objects probably had culturally

important uses as well as economic value. Bags and camel decorations would not

have had much or only very little value to “city” people and thus, in all

likelihood, were seldom traded for civilized ‘goods’. In this regard consider

the role Navajo weaving' served in their culture. As soon as trading posts were

established in Navajo territory their weaving's became the currency of exchange

between these two societies.

Turkoman main carpets were the most

valuable artifacts created by any tribe. I suspect that in classical times main

carpets were only produced for the elite or Khans. It is most probable that

these carpets were produced by at least two or three weavers. I suspect this

weaving (labor) was done for the Khans as a result of debts incurred through the

circumstances of life. In lean times poor people must have needed to borrow from

the rich. I can’t imagine a better way of repaying such debts than through the

labor of hands and hearts.

Jim Allen

Posted by Steve Price on 01-23-2008 11:39 AM:

Hi Jim

Although you posted this as a reply in the thread entitled

"Tekke Main Carpet", I've taken the liberty of splitting it off as a new thread.

The other one has gotten badly sidetracked and disrupted, and I think the ideas

you've presented here are much too interesting to keep on a back

burner.

Thanks.

Steve Price

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-24-2008 01:17 AM:

Hi Jim

That is very fascinating, trying to understand the everyday

life under which the rugs where produced certainly gives depth to the objects.

And very interesting that you think the main carpets even in classical time were

partly produced for "export" to city people. What importance would you give

silver, raiding and slavery in this economic ? Perhaps its overrated.

And

I think its interesting that artistic qualities set aside the main carpets seems

rather "democratic". They are almost same seize, the layouts basically

identical, the material and colors are of course of different quality - but it

is not like there suddenly would be a Tekke main carpet in silk and gold or even

one in double seize ?

One thing I would like to get an understanding of

is the amount of time it involved to produce a main carpet. Of course there are

many factors regarding the quality and specific circumstances which may have

varied in time and place.

In the previous tread Filiberto posted a link to a

text : http://www.richardewright.com/0807_mamonova.html#ftn2 which

has this passage regarding the weaving time in late 19th. "..in a week one

weaver is not able to weave more than 1 ½ square arshins. [12 sq. ft.] " I

suppose there must something wrong with the math, or else one person could weave

a main carpet on 50 sq. ft in a little over 1 month ? That cant be correct

?

regards Martin

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-24-2008 03:20 AM:

Perhaps one should try to make a clear distinguishing between historical

periods. Something like: a nomadic period, a period of half settlement, and a

Russian period ? And I suppose the written historical material is only valid for

the Russian period ?

regards Martin

Posted by Steve Price on 01-24-2008 08:16 AM:

Hi Martin

Concerning the amount of time it takes to weave a carpet. This link,

which is likely to be reliable, includes a statement to the effect that a

skilled weaver can make 20 pile knots per minute. This amounts to 1200 knots per

hour. For a 60 hour week (I don't think 19th century Turkmen weavers had a very

strong union, so they probably worked long hours), this totals 72,000 knots per

week. If a Tekke main carpet has around 125 knots per square inch, a skilled

weaver can tie enough knots to generate about 576 square inches (4 square feet)

per week. At that rate, a 50 square foot carpet would take between 3 and 4

months to complete.

This seems reasonable to me. It would take less time

to make a less finely knotted carpet, of course, and I've ignored every part of

the production process except actually tying the knots. For a rug woven in a

home environment by a woman weaving in her "free" time, fewer hours would

probably be spent at the loom each day, so the production would be slower. And

for the Tekke, at least, smaller items were often much more finely woven - 300

to 400 knots per square inch isn't unusual. A juval with a knot density of 400

per square inch would take about as long to produce as a main carpet with a knot

density of 125 per square inch.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Marty Grove on 01-24-2008 09:09 AM:

Time for Mains

G'Day all,

I do like the idea that Turkmen Main carpets were accorded

the respect of being a strong unit of currency within the nomads economy, by the

people themselves. That would fit well with the respect we ourselves give to the

more finely woven mains we are lucky enough to approach.

It is also

possible to imagine that the main carpet weavings which were fabulously rich in

colour, magnificent in execution and finish, of extreme fineness, the knotting

being of the most luxurious wools would be afforded a much greater value than

one of similar size which may have most of the above, with the exception that

rather than being 250 knots to the inch, it was done with 56 knots to the

inch.

We acknowledge the best Tekke pieces to demonstrate phenomenal

skills in knotting fineness, wools and colouring and therefore a greater time to

manufacture than say an equivalent size Ersari, though both are recognised to be

of Turkmen origin, so as we value them today, the finer and better they are, the

more valuable they be.

I suppose now we have to accept that carpets being

what they are, then those made from before the 1850's are of greater

significance with regard to this question of trading value because we know that

once the Western world had been introduced to them, then any former usage and

cultural meaning was altered dramatically by market forces.

But this

doesnt alter the fact that it was very likely also that as has been suggested,

that mains have always had that especial cachet of value by all the Central

Asians themselves, always being a strong item of trade or sale, before being

sought after by pickers from the West.

And from this we can also assume

that, having always been regarded as special, then it was also likely they have

survived as a direct result of having been not treated with the same vigor as

felts or lesser quality weavings, regardless of size. It might have even been

disrespectful for them to be layed directly onto the ground, floor, kang or dias

- that they always had a lesser covering beneath them.

Of course this

applies also to the best of the Yomuts, Salor, Saryk, Ersari groups and all

others which could be considered of the Central Asian pantheon, including the

Kirghiz and Uigurs of East Turkestan - they all wove at some time large main

carpets, although doubtful of the same quality that the Tekke

demonstrated.

My words are nothing new to us really, it really is just

the acceptance of Jims theory, added to what we can surmise from all the

information flowing from the writings of recent carpet ethnologers, historians

and examiners.

There is not a one of us who doesnt indulge ourselves with

having a Turkmen main or at least the desire to possess one, regardless whether

it is of superior quality or otherwise, providing it is old and

real.

Thanks Jim, I personally am very closely in agreement with your

theorem.

Regards,

Marty.

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-24-2008 09:51 AM:

Hi All

Regarding the economics of a main carpet : In addition to the

weaving time then there is of course the preparation of the wool, the spinning

of the yarn, the coloring, the preparation of the loom, the cost of the imported

colors, and the fact that a production first would be started after all the

basic necessities for surviving had been taken care of.

This is only

pure speculation, but perhaps one could estimate the total production of a main

carpet to 1 persons work in 1,5 year ? If that's not far off, I would think that

at least in the period of half settlement, were the families could put up a more

permanent large loom, a main carpet in every yurt is not unthinkable. A family

of say 10 persons should in a period of say 20 years be able to accumulate the

economic surplus equaling 1 persons work in 1,5 year.

If the main carpets

were the ultimate prestige object in the culture, and if there were no social

restrictions connected to owning one, I suppose every family would strive to get

one. Of course in varied qualities.

In the pure nomadic society the value

a main carpet may have been much higher, and perhaps there only for the elite

?

regards Martin

perhaps I should note that I do have a tiny bit

of practical experience with wool, plant coloring, spinning, twinning an so on

(but not weaving)

Posted by Jim Allen on 01-24-2008 03:14 PM:

Tekke Qualities

Tekke mains very seldom exceed 150 KPSI. Knotting density is not a good yard

stick to evaluate Tekke quality with. Many of you must have handled Pakistani

rugs with seemingly high knot counts that felt wimpy and insubstantial in your

hands. Similarly late Tekke work was often compacted with a hammer and comb to

inflate their knot counts, resulting in a very stiff fabric prone to splitting.

The quality of any Tekke weaving only becomes apparent when held in your hands

and there are great tactile differences between them. The best Tekke weavings

are both extremely supple and finely knotted. Wool quality is a measure of both

tribal strength and seasonal climate. Strong tribes occupied the best pastures

and in good years produced simply fantastic wool. I have worked with S. Batarov,

a Tekke gentleman from Turkmenistan, for many years on cartoons emulating

classical Tekke designs. We eventually got the designs right but he never could

acquire the wool or dye qualities needed to accurately reproduce anything

approaching a classical Tekke weaving. In fact nobody can and this is why truly

convincing Tekke reproductions have never been produced. The only way to learn

this subject is to handle the material. I have visited museums all around the

world looking at and handling Turkoman weaving's in their possession. Looking at

pictures in books then going out and buying pieces that one thinks are similar

is simply a recipe for disaster. Unfortunately many museums have become less

responsive to such endeavors but a well crafted and sincere letter of

introduction along with a request to examine any museum’s collection is still

the best way to learn about what I am trying to describe here.

Jim

Allen

Posted by Steve Price on 01-24-2008 09:53 PM:

Hi Martin

Considering only the actual weaving time, I estimated that a

Tekke main carpet requires about 4 person-months of labor. Factoring in all the

other things that go into the production, you estimate about 18 person-months of

labor. If our estimates are both right, the actual weaving only amounts to about

one-fourth to one-fifth of the total labor required.

I have no

experience with producing carpets, but have the impression that the weaving is

the major part of the labor involved in doing so. I don't know where that

impression came from, but it doesn't matter very much. Would you agree, then,

that the actual weaving accounts for less than 25% of the total labor

involved?

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-25-2008 01:52 AM:

Hi Steve

I certainly may have overestimated the non-weaving parts of

the production in trying to get a picture of the carpets relative economic

value. And originally I would also have estimated the weaving time to be at

least 3 times more then what your link suggest. But all the factors in the

productions of the wool (which should also include the taking care of the

sheeps), the collecting of plants and their preparation for the coloring, the

spinning and the twinning and so on of course must have been very time

consuming.

But I suppose that my point is that the relative economic value of

the carpets in the time of their production (even if you try to be conservative

about the figures) didn't make them totally out of reach for ordinary people.

regards Martin

Posted by Steve Price on 01-25-2008 05:44 AM:

Hi Martin

It does appear from your analysis that a main carpet was

probably within the means of many, maybe most Turkmen families. Apportioning

costs other than weaving becomes a little complicated because some of the costs

can't be exclusively assigned to producing a carpet. Raising and tending the

sheep, for example, generates wool, but also generates sheepskin, milk and meat.

I have no idea how much labor it takes to produce and apply the dyes to color

the wool used in a single carpet or to spin enough wool for the carpet. A full

analysis of the labor input in creating a Turkmen main carpet would be

interesting. I don't know of any published sources for this, but there probably

are some in the Russian literature.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-25-2008 10:50 AM:

Hi All

Of course the economics of the pure nomadic society is even

more speculative, but I suppose the relative value of the carpets in a less

specialized economy could have been exceedingly higher, and the main carpets

there as Jim suggest only for the elite.

On the other hand one could wonder:

If the carpets were the result of the elites accumulated wealth in the nomadic

society, what then became of that accumulation in the more specialized economy ?

Normally the rich get richer, and the poor get poorer when economies get

specialized. Where are the extra-extra ordinary carpets from the 19th ? The

carpets that would be the elites way of setting themselves aside ? Would this

differentiation be expressed only in the wool and coloring qualities? In our

days rich people are not that subtile in their bragging :-) But perhaps it all

went up in warfare, as Jim suggested in the previous tread. Importing firearms

must have been expensive.

And I hope that Jim will follow up on his

thoughts in the previous tread on categorizing the differences of the main

carpets. I understand that it is probably problematic doing it only on design,

and that it certainly aren't just something like "Chemshe gul group 1, Gurbaghe

gul group 2".

But still there are obvious a great variety in the main

carpets, and any attempt on categorizing them would be extremely interesting and

surely heroic :-)

regards Martin

Posted by Richard Larkin on 01-25-2008 05:03 PM:

Hi all,

I am following this discussion with great interest and not a

little fascination. I certainly don't want to spoil the fun, but I wonder where

it is going. The seminal statement is Jim's summary from the paper he is working

on. A careful reading of that post indicates to me that most of what he is

saying is surmise based on opinion, analogy to other cultures, induction,

speculation, etc., all of it apparently leavened with some data from O'Donovan

(a work to which I do not have access just now). Thus, I wonder how it is

possible to conclude from this foundation what the collective attitude or

approach of the tribes was to the weaving of main carpets or any of the other

standard items in their repertoire. I suppose it would be necessary to have a

much more comprehensive understanding than we have of the daily lives of nomadic

Turkoman peoples to know just where in their hierarchy of priorities the weaving

of carpets or other trappings fell. I mean in terms of how much of their

available time and effort they devoted to the actual weaving, and whether they

gave any special place to the weaving of special items, such as main carpets, as

contrasted with (presumably) more mundane items.

All that said, I

emphatically agree with Jim that the best (presumably early) Turkoman work

demonstrates a carefully considered approach to the weaving in terms of the

employment of specific weaving techniques or practices in to obtain a specific

character in the resulting fabric. I don't have the expertise in weaving to list

these choices, but they involve weight and quality of materials and their

spacing and handling in the weaving process. I'm sure I haven't handled the

number of examples Jim has, but I have handled a few. I particularly recall some

early Salor rugs. There was an exquisite quality about them that, it seemed, had

to have been understood in advance and planned. It contrasted with most other

handwoven rugs, in which one had the impression the secondary weaving decisions

had been made somewhat arbitrarily, and the qualilty of the resulting fabric was

more an accident than an achievement.

Posted by James Blanchard on 01-25-2008 10:38 PM:

Hi all,

For what it's worth, I have had experienced Central Asian rug

repairers (based in Peshawar now) tell me that by far the most difficult rug to

repair is a good old Tekke (I am not sure whether they have tried Salor). They

said that it is almost impossible to match the wool and colour unless they have

a fragment of comparable age and quality. I think this speaks to Jim's statement

about how difficult it is to reproduce a good old Tekke.

James.

Posted by Jim Allen on 01-25-2008 11:22 PM:

Tekke mains

In my opinion Tekke mains whose designs are entirely regular and

uninterrupted are commercial and in all probability late. Culturally important

Tekke mains have interruptions in their border renditions and tertiary field

ornaments. We have already mentioned in a previous thread the singular

appearance of a single chuval gull in the border of some old looking Tekke

mains. I have examples of other odd insertions in Tekke mains archived on my

hard drive. In conclusion it seems to me that these tertiary field additions and

variations in the main border decorations are indicative of culturally important

Tekke mains. The differences in quality between a commercial circa 1880 Tekke

main and say an 1850’s Tekke main are not qualitatively apparent. In other words

there is very little appreciable difference in their physical quality. The main

periods of Tekke main production fall into four main periods. The earliest

examples any of us are likely to ever see are from the first half of the 18th

century. Tekke weavings went seriously down in the second half of the 18th

century and their borders were not traditional. In fact Tekke work of all kinds

from this period show borders strongly influenced by Yomud iconography. One also

encounters poor muddy dyes such as reds with darkish residues lacking clarity in

this period. The reason is simple. The Tekke were not in possession of the best

pastures or good clean sources of water during these years because they were

secondary to the stronger Yomud. Just after the turn of the 19th century the

Tekke again became strong again and in control of better pastures and water and

here we see the brilliant arterial red we all love so much in their work. In

these first half of the 19th century rugs the number of gulls found on Tekke

bags increased and in fact I believe the same applies for these early 19th

century Tekke mains. You can see examples of these high gull count rugs in Elmby

and in some German museum collections. After the Tekke were run off from the

Caspian sea coast region they fled to the Merv Oasis. Tekke mains from this Merv

period are of course much more numerous and these are the ones with red and blue

stripe kilim ends and the 4X10 arrangement of gulls. The quality of these rugs

was outstanding and important pieces were “personalized” by the asymmetric

additions mentioned earlier. After about 1880 Tekke mains were still made of

very high quality materials but their individuality was lost and replaced by a

bald uniformity. This subject would require thousands of words to adequately

describe but this is the general outline that I use to judge these rugs by.

Jim Allen

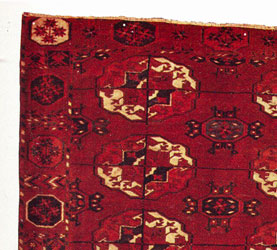

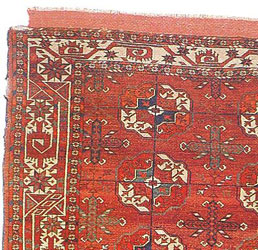

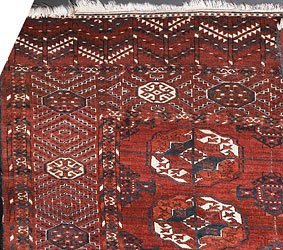

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-26-2008 05:20 AM:

Hi All

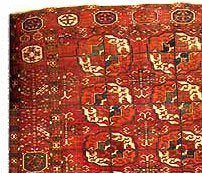

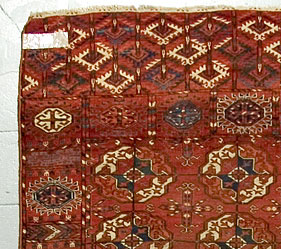

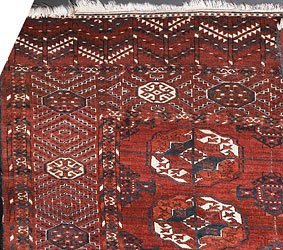

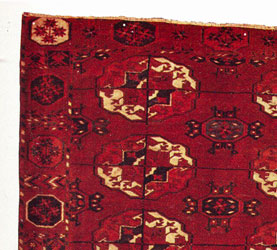

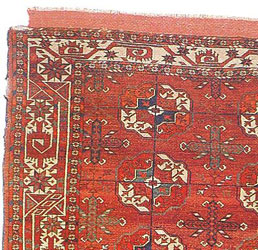

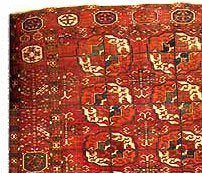

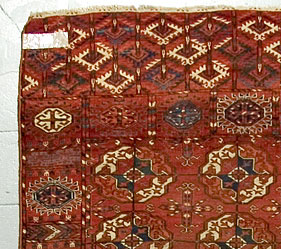

I take the liberty of an attempt on illustrating Jims timeline

with material from previous treads (copy paste is one of the qualities of the

net )

)

a. Azardi,

Turkoman Carpets. According to Azardi pre-18th century

b. Yomut

border influence ? Mr. Reuben's article in Hail 145.

c.

Elmby.

d. Pietros carpet from previous tread

e. Later

commercial rug ?

The borders are of course one of the must

obvious place to look for variations in the layout of the carpets. The star

& octagon border seems to be accepted as the oldest border layout ? (I do

think that I have seen very late carpets with the star & octagon border, but

in these matters there seems to be no rules without exceptions).

I suppose

the tekke main gul is still the primarily design identification of a Tekke main

carpet. And I think it is interesting that there in the articulation of these

main guls also seems to be some rather significant aesthetical variations,

variations which are not only related to the flattening of the layout which is

generally seen as a decline in carpets design.

Unfortunately I haven't been

able to find a copy of Hail 145 were Mr. Reuben has an article on the main

carpets, I will try to order once more from Hali's back catalogue. I suppose

that there is some relevant information in that article ?

Then there is

the whole matter of the quality of the wool, the structure and the colors.

Issues which are of course are totally essential to the history and presence of

the carpets. And these qualities are hardly describable in neither literature or

photos. I certainly do have a 100% respect for Allen's and others direct

experience in these matters.

regards

Martin

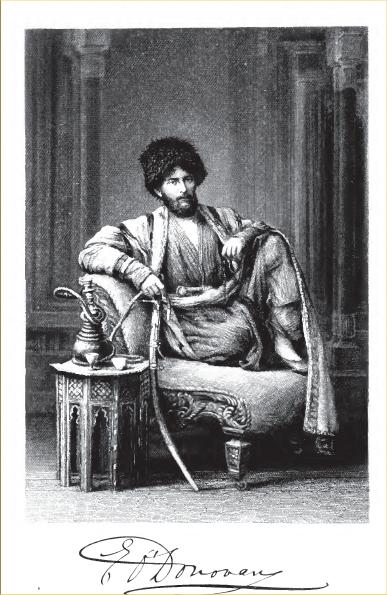

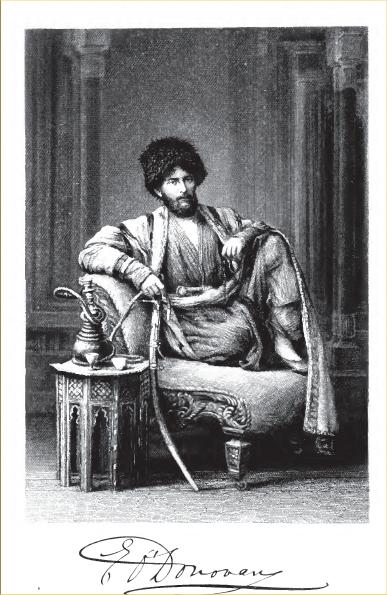

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 01-26-2008 07:14 AM:

For all interested in O'Donovan’s book “Merv, a story of adventure and

captivity (1883)” : you can download it from this web site:

http://www.archive.org/details/mervstoryofadven00odoniala

I downloaded a 11 MB B/W PDF version of it… It will go in my looong

waiting line of books that I still have to read

Warning: since it seems that

there are no images in the book but this one:

You could spare yourself

the hassle of a long download and go for the 639 KB text–only

file.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Jim Allen on 01-26-2008 11:48 AM:

O'Donovan

O’Donovan was a 19th century British secret agent comparable to the semi

mythic James Bond of recent literature. An ex-military man who had served among

the horse mounted Indians in the American Southwest he was uniquely qualified to

be the Queen’s man in Central Asia. His job was to scout out the Turcoman tribes

who existed in the vast hinterlands separating the Russian southern expansion

from the British northward expansion. Two earlier British agents, Connolly and

Smith, had been beheaded by the Afghans in the 1830’s at Bukhara. O’Donovan was

a superb observer who used his spy glass and pocket watch to great advantage in

his information gathering. In my opinion there isn’t one single other book in

the world giving a more realistic look into the reality of nomadic life among

the Turcoman. By the way I downloaded the 24 MB version via Comcast cable in

less than one minute. What I do not understand is why there are only some 380

pages? My first edition has about 800 pages and is in two volumes.

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-26-2008 12:26 PM:

How Long Is Long?

The working looms I saw in Turkey had two or more women making a single 5x8

or so carpet. They worked very quickly and could probably make a rug in a couple

of months or so. A larger Tekke main carpet may have taken longer, but could

have been completed during a seasonal stay at one location. And with several

women working at the same time (like a barn-raising in the old west) the work

could go rather quickly. Also, with several women working together, the style

would stay quite similar over several carpets they worked on together over time

- along with the dyes and wool.

On the other hand, we were treated to a

talk by Richard Isaacson at our recent Seattle Textile And Rug Society meeting.

http://www.seattletextileandrugsociety.org/

He thinks that

it would take from one to three years to make a single mixed-technique

tent band.

There is speculation that these may have been made by

"specialists" and sold to the family of the newly married couple, although there

is no proof of this as yet. It would be rather difficult to have more than one

person weaving a tent band only a foot wide by 45 feet long.

There is a lot

of gnashing of teeth, fisticuffs and scuffles regarding the origin of Turkmen

rug motifs, but it is extremely difficult to determine the provenance of many

tent bands due to the dissimilarity of the motifs (and technique of tent band

construction) compared to the more distinct tribal differences in their carpet

designs.

The fact that the trellis tent used by these peoples was developed

thousands of years ago, and way before any of the extant main carpets were

woven, it is possible that many of the tent band designs (the tent band was a

structural component of the tent - some of them actually provide support so the

tent does not fall down) pre-date the evolution of main carpet designs.

Here

is a statement from the Jozan.net site about the exhibition and book from

Richard:

"A Central Asian tent band is typically one foot wide by 45 feet

long – an imposing scale. Because of the large size, a tent band would be woven

in one piece on a narrow horizontal loom placed on the ground outside the

trellis tent, rather than inside the shelter of the tent. It could take one to

three years to complete a single tent band."

http://www.jozan.net/2006/tent_bands_of_central_asia.asp

All

of this argues for a society stable enough that a project which took three years

to complete was even possible. Almost as long as it will take Filiberto to

finish reading those books.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Sophia Gates on 01-27-2008 01:47 AM:

On the topic of valuable things: I saw a Turkoman double-faced silk velvet

rein for a horse at a Rug Society meeting several years ago.

I suspect

that objects like this were those "really special" things that showed great

wealth and status.

It was probably one of the most sumptuous objects I

have ever seen or touched. I think it was Tekke, it had the touch of the silk

details in my old ak chuval, delicious and soft and fine.

It was a deep

teal as I recall. Absolutely amazing.

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-27-2008 05:37 AM:

Hi All

It seems to be accepted that smaller fine objects like

Asmalyk's, Torbas and perhaps the small (wedding-) rugs, where a part of the

dowry, objects which the coming bride made herself. Apart from the specifc and

complicated cultural and symbolic implications, that could have been a way of

her bringing valuable objects to the new home, and at the same time an

affirmation that she would be able to produce valuable objects for household in

the future. I would think it would be reasonable that these objects woven by the

married women (and their children ?) would have been larger and even more

valuable objects like the main carpets or perhaps tent bands, and perhaps

objects with trade value? The tent bands may of course have been very time

consuming, but I suppose there is no specially technical reason why they

shouldn't have been produced in a house hold ? I suppose the fabric was rolled

up while being produced, or did they require a permanent loom in their full

length ?

It is of course a mixture, but what I am trying to figure out is

in what degree the carpets and woven objects were utilitarian or artistic

luxury.

It is of course more easy to ask a lot of questions in these

matters then it is to answer them. The hierarchic structure and the women's role

in the society seems to be basic for an understanding of the rugs. And there is

probably no way around a lot of reading

Are there any recommendations on

relevant anthropological/sociological literature regarding tribe culture in the

area ? Perhaps on the Khirgiz, who as Paul Smith suggest remained nomadic up in

history ?

regards Martin

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-27-2008 07:24 AM:

Hi Sophia Gates

Is it possible you could post pictures of the

double-faced silk velvet rein for a horse, or a similar piece ? I haven't seen

something like that, and it sounds very interesting.

regards Martin

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-27-2008 09:38 AM:

annual wool shipments to Tekke weavers

O'Donovan's observation that the Tekke received their materials in annual

allotments is interesting. Was it being returned to the Tekke weavers, after

having been processed elsewhere? Was it purchased from a distributor of rug

supplies originating, possibly, in many other places, in an as yet unknown chain

of manufacture?

Certainly Tekke flock's wool of later times, when

photography had been invented, had nothing to do with classic era Tekke rugs.

O'Donovan's observation, in this thread, at least, is not clear enough about

what he saw. Was the annual shipment dyed in the wool? Did the annual shipment

arrive already spun into yarns? Sue

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-27-2008 01:23 PM:

Hi All

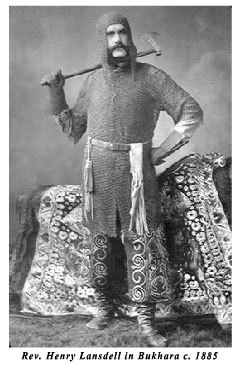

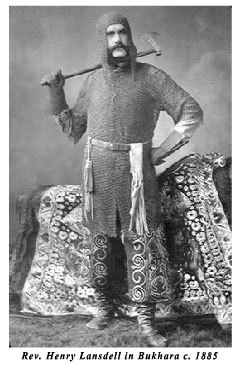

I cant help posting this picture taken from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Geok-Tepe

It is supposed

to be from before the defeat to the Russians at Geok Tepe in 1881. It gives

perhaps an image of what kind of scary guys O'Donovan was up against. Quite a

contrast to the beauty of the rugs. And what on earth are they wearing ?

flatwoven iron ?

Martin

Posted by Lloyd Kannenberg on 01-27-2008 01:57 PM:

Hello Martin and all,

It looks like they are wearing chain mail

outfits. When I was in Georgia (Caucasus, 1980) I was told that the Khevsurs

used to wear chain mail, with crosses no less, because their ancestors had been

Crusaders. I had no way of verifying that!

Best wishes,

Lloyd

Kannenberg

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-27-2008 02:23 PM:

Martin, That is defensive armor. Chain mail. Sue

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-27-2008 03:48 PM:

Don't Break The Chain!

Paul,

Could be Halloween costumes.

Either that or they didn't want

to get sunburned.

It looks like chain-mail protective covering taken to an

extreme. In the middle ages, a knight wore chain-mail shirt and leg coverings,

but with a helmet. Here the helmet is replaced by more chain mail.

Notice

that they all have a rifle, but also a shield, sword and the chain-mail. Most of

the fighting was done hand-to-hand.

If you ever visit a museum with old

hand-to-hand combat weapons, there were some very bizarre things made to inflict

mortal damage to flesh.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-27-2008 05:00 PM:

Hi All

Then chain mail it is. I was just completely baffled by the

combination of firearms, iron armor and the year 1880.

Iron armor can´t have

been very effective against the Russians. But I suppose it make sense as the

Tekke didn't only have the Russians as opponents.

The four men are

uniformed exactly the same way, and that gives the impression of an, perhaps

strangely equipped, but still rather well organized army. And an organized army

(with imported equipment ?)certainly is an indication of a rather hierarchic

society.

I love the photo, it totally turns my own notions of the Turkmen

- imagining these four guys sitting on a main carpet

And now I better understand

the front page on http://www.richardewright.com/ :

I actually thought it

was some kind of opera picture.

regards Martin

Posted by Richard Larkin on 01-27-2008 06:11 PM:

Hi all,

Anybody care to analyze that carpet behind the Rev. Lansdell?

Is it an embroidered felt?

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 01-28-2008 07:56 AM:

Hi Martin,

That’s a Wikipedia mistake: those are not Turkmen but Khevsurs

from Northern Georgia (Caucasian Georgia, I mean  ).

).

This is a Wikipedia page about

them, with another interesting picture:

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khevsureti

And this is a link

to another similar photo:

http://www.arco-iris.com/George/images/khevsurians_02.jpg

The

swords are Georgian anyway, and the daggers (kindjals) are typically

Caucasian.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Martin Andersen on 01-28-2008 08:27 AM:

Hi Filiberto

Thanks for the correction. I will leave the link to

Wikipedia but remove the picture (so it doesn't attracts to must

attention).

Sorry for the digression of the tread.

regards Martin

Posted by Marty Grove on 01-28-2008 09:45 AM:

Digression again

G'day all,

For Filiberto (another for your future pile) and those who

like to read about the historical country which produced the weavings we love,

here is another book I can recommend as an absolutely fascinating and

spellbinding read about the Caucasus 'Sabres of Paradise' written by Lesley

Blanch I forget when, and its main protagonist (Shamyl - the Lion of Daghestan)

against the Russian invasions of the Caucasus region.

The people and

country described in this book are often extremely tough, fervent even maniacal

Muslims living in some of the most impossible eyries it is possible to imagine,

in a climate which certainly would not suit me, and of a particularly

bloodthirsty nature, and armed to the extreme with a variety of weapons, one of

which is their knife, tied by custom but not literally, to their manhood. These

people kill in very unpleasant ways! (And the women are often

fiercest).

Regards,

Marty.

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 01-28-2008 11:37 AM:

Well, thanks Marty: another book to add to my waiting list (this one goes in

the wish list as well).

Filiberto

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-30-2008 11:33 AM:

I don't yet have Richard Isaacson's book on tent bands but it is on my long

''to buy'' list. I have serious doubts, though, for many technical reasons, that

these tent bands were woven on horizontal ground looms. I think they were more

likely woven on rather low tech specialty looms.

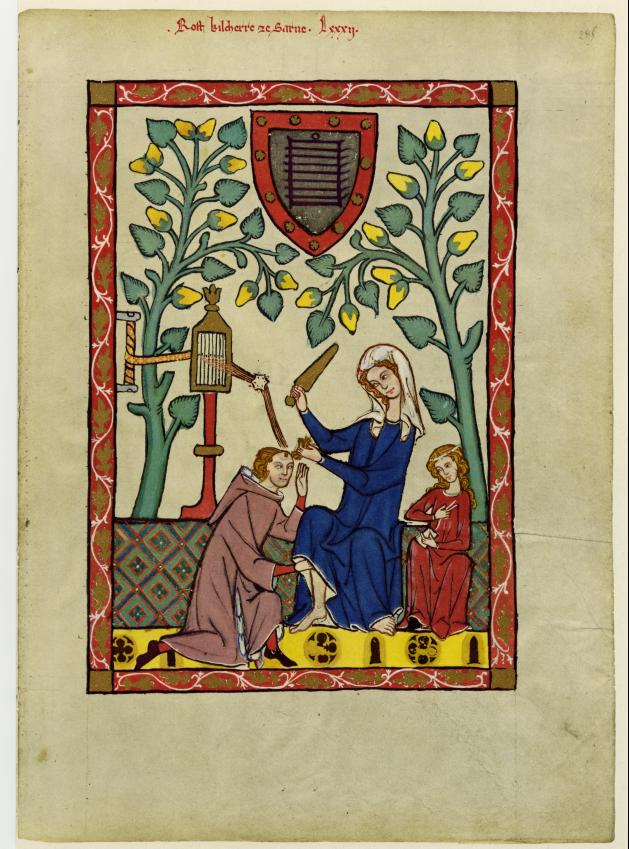

I have emailed Steve two

jpegs of looms which I think Turkmen band looms may have fit somewhere

in-between. One of the pictures is of a modern low tech band loom. The other is

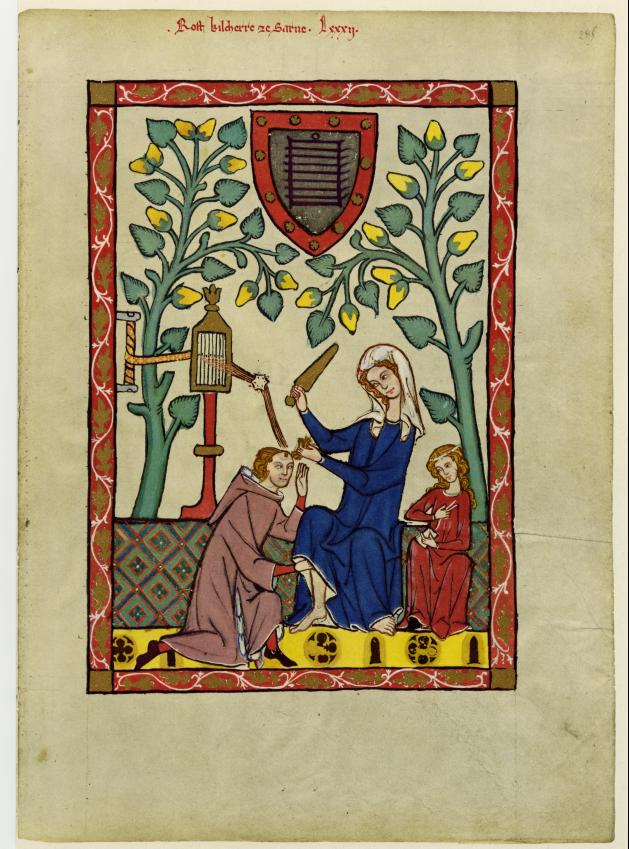

an illustration from the Codex Manesse, 1305-1340 AD. I am sure there are other

possibilities of band loom configurations I am not yet aware of that would have

served, too, far less problematically than horizontal ground looms. Portable,

too. I haven't done any tests yet in this area yet, though. I intend to get to

that sometime soon. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 01-30-2008 11:42 AM:

Hi Sue

Only one link to an image arrived. Here's that

image:

I agree that ground looms 50 feet long seems unlikely.

Steve

Price

Posted by Steve Price on 01-30-2008 01:05 PM:

Hi Again

Here's the second image that Sue sent:

Steve Price

Posted by Jim Allen on 01-30-2008 05:22 PM:

Tent Band Looms

I believe the tent bands were done outside horizontally on the ground. The

looms were quite simple; the top warps were tied together and these small

bundles were staked out into the ground. The weaving was unwound to the first

open warps, I am assuming the weaving is well underway, and then one would

unwind a length of warp threads and tie them off, at whatever length required,

and stake them into the ground. I am assuming they tied a loop knot in an

unbroken thread. They probably used a special slip knot for this job. The

tension was applied by inserting a log or something similar underneath the

already woven section to raise it up off the ground pulling up on the staked out

warp threads. This way the effective loom size was kept relatively short and

required the absolute minimum of materials. In fact all the materials needed

could be produced on site just about anywhere they would go. They only carried

spindles, combs, wool, dye stuff, and actual weaving's in some state of

manufacture. You can just about bet that this work went on year round with

dyeing and spinning taking up far more time than you probably think it did.

Jim Allen

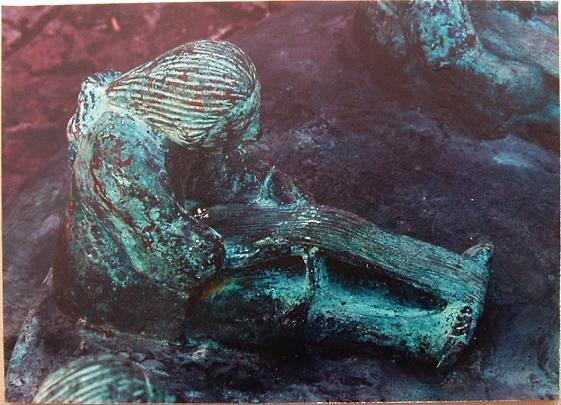

Posted by James Blanchard on 01-30-2008 05:45 PM:

Simple looms...

Hi all,

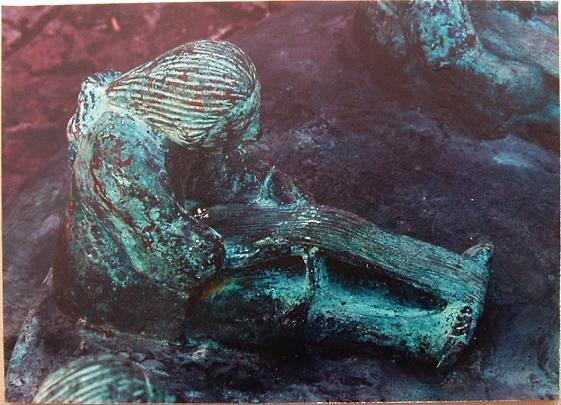

Speaking of simple looms, here are a couple of photos from the

National Minorities Museum in Kunming (Yunnan, China). These are from bronze

figures dated to the Western Han Dynasty (c. 200 BCE to 45 AD). Of course, the

socio-cultural context was different and the weaving process for pile weaving

would differ, but I was struck by how rudimentary the process was. Also, note

the presence of a "weaving supervisor/teacher".

James.

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-30-2008 06:53 PM:

I've been reading the 639kb version of the O'Donovan book which Filiberto

linked. There are no answers to the questions I've asked about his wool

observations there. I suppose if he had any good Tekke textile information

someone would have found it by now.

He didn't seem too interested even in

the Tekke weavings he was given. He felt obliged to accept these gifts but was

really more concerned they would overburden the horses. And the one thing you

can be sure of, after reading what he has to say, there was no way he would have

left his tea and sugar behind instead of carpets, if it came down to either/or.

I'm ok with that. He had other things on his mind.

What I am not ok with is

his totally pedestrian and historically ignorant trashing of Akhal Teke horses.

I cut O'Donovan the same slack in that as in textiles, though, but this is a

thread on the Tekke experience and these horses need defending. They had a

central and important place in the Tekke experience. Read this link and judge

for yourselves. Sue

http://www.equiworld.net/uk/horsecare/Breeds/akhalteke/

Posted by Richard Larkin on 01-30-2008 07:35 PM:

Hey Sue,

Heck of a link!

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Jim Allen on 01-30-2008 07:36 PM:

The Merv Oasis

The unabridged first edition of O'Donovan's book had many pictures and maps

and twice the information as it had twice the pages. This condensed version

lacks just about all the pertinent details. Jim

Posted by Steve Price on 01-30-2008 09:56 PM:

Hi People

I live in Virginia's horse country, lease pasture land to a

neighbor for his horse, and can often see three or four horses by looking out a

window. Despite this, I know next to nothing about the animals except that they

are pretty cool to watch. But I suspect that if I showed that article to any of

my horse loving neighbors, they'd get some laughs out of it. It doesn't read

like an objective description of Akhal Teke horses. I suspect that there's more

than a germ of truth in it, but an awful lot of romanticized hype as

well.

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-31-2008 09:32 AM:

http://www.silk-road.com/artl/maslow.html

Posted by Marla_Mallett on 01-31-2008 10:41 AM:

Here’s

the type of loom used throughout the majority of the Turkic areas of Western and

Central Asia for medium-width warp-faced bands made for jajims and tent bands.

(It’s a photo of a NW Persian Shahsevan weaver from Jenny Housego’s book, TRIBAL

RUGS.) The primary shed is formed with a shed stick, and the counter shed by a

heddle rod—in this case, a single heddle bar suspended from above. In other

versions, the counter shed is formed within an open primary shed, as is done

typically by Kurdish kilim weavers who stake their warps to the ground. This is

all that would have been needed for full-pile tent bands. The mixed-technique

bands that combined flat-weave areas and pile would have needed the capability

of opening four different sheds, and that could be accomplished by suspending

four heddle bars from above (most likely in two counterbalanced pairs). These

bands required more specialized skills. As for general loom type, the critical

factor is the extreme tension under which the very closely spaced, sticky warp

must be held. The length of the warp is irrelevant. If necessary, the unused

warp can be temporarily gathered into a large knot at any point and staked down

to the ground at that point. Rolling up the finished portion of the band is also

possible if there are space limitations. Narrow pack bands and belts (perhaps 1

to 4 inches in width) are often made with other loom arrangements - cards, rigid

heddle, or multiple harness arrangements. My website pages on tent band

construction explain the reasons why I think the mixed-technique bands were very

likely produced by specialist weavers: www.marlamallett.com/bands.htm. There is also a photo of a

Goklan weaver on that page - using a ground loom for a band.

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-31-2008 01:35 PM:

I think the extreme length of time needed to weave wool pile tent bands,

along with the yarn stress from the constant lifting and lowering of the unwoven

warp length, done for each and every row of weaving, would fatigue the warp

fibers down to their microstructure. That is not good idea. In 40 foot warp

faced weaving, an especially bad idea, unless repairing and burying the evidence

of an awfully lot of broken warps, probably all in the same areas, is ok. Better

to expose small amounts of warp to stress as the weaving progresses and let the

rest of it rest.

I think weaving pile tent bands was a weaver's specialty

because of the good idea someone had to use specialty looms. Not quite as low

tech as horizontal ground looms but still pretty low tech. Now if all of these

tent bands are just loaded with broken warp repairs I might change my mind. I

don't know whether or not that is the case. I've not had the opportunity to see,

even one, in person. However, I have never seen bad horizontal loom selvages on

any tent band photos yet. Has anybody else? Seeing evidence of that type might

change my mind, too. Sue

Posted by Marla Mallett on 01-31-2008 03:50 PM:

Sue,

Up and down movement of the warp yarns occurs only in FRONT of a

shed stick, or lease sticks if no shed stick is used. The remainder of the

warp—no matter how long—is stationary, and subject to no stress at all.

Marla

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-31-2008 08:58 PM:

Marla,

Are you saying that in a continuos fine yarn warp, under

extreme tension and manipulation for a very long time, stress doesn't travel

through the yarn? Sue

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 01-31-2008 11:01 PM:

Wefted, not warped

Sue,

The warps in a mixed technique tent band are sinuous, the wefts

are taut. This means that the warps do not need to be under tension during the

entire weaving process.

Patrick Weiler (under tension)

Posted by Marla Mallett on 01-31-2008 11:01 PM:

Sue,

None of the warps used for the warp-faced Western or Central

Asian tent bands and jajims are “fine yarn warps.” They are invariably composed

of combed, long staple wools that are tightly overspun and then plied so that

they are sturdy, strong and elastic. Especially, for the tent bands! After all,

these yarns are spun and plied for girths intended to help hold up lattice

tents! There are no problems with such yarns withstanding stress during the

weaving process.

Marla

Posted by Marla Mallett on 01-31-2008 11:21 PM:

Pat,

You are right that the individual warp yarns in a warp-faced

structure do indeed take on a sinuous course in the finished fabric, with wefts

that are straight. The warps do, however, have to be held under quite strong

tension throughout the weaving process. Wool warp yarns that are closely crowded

for these bands are “sticky”, i.e., they tend to cling together. Only if they

are held under quite strong tension is it possible to keep changing the sheds.

Thus elasticity (created by overspinning) is perhaps the most critical yarn

characteristic for such warps.

Marla

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 02-02-2008 09:04 AM:

tent bands

Patrick,

What Marla has explained to you tells the tale of shrinkage. In

other words a 50 foot tent band could have been ll over 60 feet before it was

cut from the loom. Just to give you an idea of the warp tension involved in

weaving these mixed tehnique wool tent bands. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 02-02-2008 09:17 AM:

Re: tent bands

quote:

Originally posted by Sue Zimmerman

... a 50 foot tent band could

have been ll over 60 feet before it was cut from the loom.

I own a Turkmen tent band, and I think it would tear from

stretching long before it's length extended by 20%. I've also handled tentbands

of various kinds, and none had anything approaching that level of elasticity. I

tire of asking you this question so often, but apart from the fact that it

occurred to you to say it, do you have any evidence that tentbands shorten

significantly (I'd call 5% significant) when removed from a loom?

Steve

Price

Posted by Sue Zimmeran on 02-02-2008 09:28 AM:

tent bands

Steve,

Marla know about shrinkage. I did not make it up. Just ask her.

She will tell you about it better than I could.

Marla,

I classify

a 2py worsted warp yarn with a diameter of 1 mm or less as a ''fine yarn warp''.

Do you have a different definition? Sue

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-02-2008 02:28 PM:

I’m afraid that this discussion has become a bit absurd—from several

perspectives.

First, I can’t imagine a 60 foot tent band shrinking to 50

feet unless it were plopped in a kettle of boiling water. A SLIGHT shrinkage

when a band is no longer under tension is inevitable, but it would be

negligible—especially when knotted pile is included in the structure. The

“elasticity” of the overspun warp yarns merely allows for easier manipulation

during the weaving process and prevents warp breakage.

Second, these

bands are not “cut from the loom.” Rods are used to stake the warp to the

ground, and these are merely slid out of the warp loops. Lengths of unwoven

warps at the two ends serve as ties on the bands’ ends.

Third, anyone

who speaks of “worsted” warp yarns when speaking of tent bands surely has no

familiarity with the overspun wools used for the warp-faced bands and jajims of

Western and Central Asia. Worsted yarns, used for wool suiting, are worlds apart

in their characteristics from Central Asian rug and tent band warps, with little

in common other than their use of combed long-stable fibers.

Fourth, I

can’t imagine what is meant by “the extreme length of time needed to weave wool

pile tent bands”? How would this affect the choice of loom type? Asian tribal

weavers are extremely efficient and in their weaving communities have adapted

equipment over the years to best suit the processes, structures and products

involved as well as their living and working arrangements.

Fifth, it

seems odd to reiterate the belief that some other kind of loom must have been

used when faced with photographs of band loom setups in actual use by Azeri

Turkish and Goklan (Yomut Turkmen) weavers. What does the statement “the good

idea someone had to use specialty looms” mean? What specific features would

represent an improvement? “Low tech” tells us nothing. The case for another kind

of loom is hardly bolstered by a European Medieval drawing of a narrow rigid

heddle/card loom being used for a narrow strap (artistic license and a fantasy

itself, as there is no reason for the two devices to be used together) and a

flimsy band loom with tiny rollers that would never accommodate the huge rolls

of a long tent band with either full pile or partial pile. The uneven buildup of

a partial pile band on a roller beam would quickly create uneven tension in the

warp. Furthermore, the two heddle bars on the band loom in the photo are much

less practical than the shed stick/heddle bar arrangement used throughout

Western and Central Asia for wool warps held under severe tension. It would

certainly be impractical for a weaver seated at the SIDE of this loom in order

to operate the two treadles, to tie knotted pile across the width of a band! To

hypothesize the use of “specialty looms,” one needs to describe specific loom

features that would improve the process.

It is easy for Western weavers

to speak condescendingly of “low tech” looms. But most would very quickly find

their fancy jack, counterbalance or contra-marche looms unsuited to the high

levels of stress produced by pile carpet weaving. Most do not understand the

logic of a secondary shed opened WITHIN a primary shed—and that the conventional

shedding arrangements they are used to using are almost impossible with a wide

carpet warp. Thus most Western writers who have explained Asian looms actually

get it wrong.

Marla

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 02-02-2008 04:01 PM:

Very Helpful

Marla,

You note that the warps of a tent band, while under

construction, need to be held under quite strong tension.

Does this indicate

that the loom could not be disassembled and moved during the entire weaving

process, which according to Richard Isaacson could take more than a year?

Our

romantic, western notions describe a typical nomadic weaver either making an

entire piece during a stay at a particular stop, or assembling and then

disassembling the loom when moving to other locations.

And thanks for

reducing the level of absurdity. I sometimes attempt to interject a lighthearted

comment, but I try not to enter the realm of the absurd except for comic

relief.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Richard Larkin on 02-02-2008 04:11 PM:

Hi Folks,

Among the many and oft documented sins of the traditional

rug lilterature, it seems, is the fact that (in my estimation) there is a lot of

offhand discussion and ill-informed description of what the weavers are doing

and how they are doing it. Yet, in reading Marla's comments (here and

elsewhere), one has the impression the whole process is highly technical, even

in rustic weaving. There's no substitute in knowing what you are talking aboput

if you are going to get into these issues.

Posted by Steve Price on 02-02-2008 04:31 PM:

quote:

Originally posted by Richard Larkin

There's no substitute in

knowing what you are talking about if you are going to get into these issues.

Making authoritative pronouncements without taking the trouble

to find out whether they even make sense is arrogant, self-aggrandizing, and an

imposition on those who read them. There's one rug site virtually dedicated to

the practice. This isn't it.

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 02-02-2008 06:01 PM:

Marla,

I have a 1850s Tekke torba. It has a sett of 24 wpi. The warps

are worsted-spun and are less than 1 mm in diameter. Each of it's two plys

averages 28 fibers.Thanks to moths, I know that the final two ply yarn has 28

twists per inch. In it's 16 inches of weaving there are 8 warp breaks. In just

16 inches of weaving. And it' s uneven.

I am a spinner. For those who

don't know, good spinning is about spinning to specification. Spinning to

specification is what spinning is about. I am capable of replicating my torba's

warps to specification. For singles of 28 fibers I use a 10 gram spindle and

overtwist the yarn to 42 twists an inch because a third of that twist is unspun

in the plying process. It takes 45 minutes, on my 400 dollar combs, to properly

process 1 ounce of fiber at these specifications, and only a third of that is

suitable for warp yarns of my torba's specifications.

I only have low

tech looms and have probably more respect and understanding of the efforts that

went into these tent bands than most. I would like to make a sample with my own

designs because that is what artists do. I cannot afford to buy a tent band to

analyze yarns and there is no structural analysis or measured photos suitable

enough for that undertaking. From my own testing, experience, time, money, and

fiber, mixed technique wool tent bands and horizontal ground looms is a way to

risky investment. I am sure I will not be the first to have to invent a better

solution to that problem. I'll figure it out. Sue

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-02-2008 08:18 PM:

Pat,

With “ground looms” such as those shown in my two photos, it’s a

very easy matter to simply pull up the stakes securing the rods at the front and

back ends of the warps. The weaver merely rolls up the warp and puts it on her

horse. It helps to keep the loose, unwoven warp in order if a cloth is rolled up

along with the warp, or if a series of sticks are inserted at intervals. The

whole bundle can be wrapped in a cloth to keep it in order. Alternately, the

loose, unwoven warp can be tied tightly at intervals with cords, and the whole

long length “chained” (pulled through successive loops). A heddle bar, such as

shown in the Azeri (Shahsevan) photo, can simply be detached from the tripod

frame and rolled up inside the bundle along with the warp (with heddles still in

place), and the tripod collapsed. It’s surely the easiest of all “looms” to

transport. It would require a couple of extra hands to get the warp staked down

again properly at the new location.

I can’t imagine any tent band

requiring a year’s worth of weaving time. With a full pile band, it should be

easy to figure the total square footage, and compare that with the time needed

for comparable knotted-pile carpets. The warp-faced “mixed technique” bands

(with warp-faced plain weave and knotted pile), while requiring a much greater

level of skill and experience (if you don’t believe this, please read my website

pages on band construction), should require a fraction of the time, since much

less of the surface is knotted.

As for the TOTAL TIME required, I think

few people realize how terribly time-consuming wool preparation, i.e. wool

cleaning, sorting, and carding or combing is. Or how time consuming spinning is.

Add to that the time spent in collecting and processing dye materials, and the

work that proceeds the actual weaving is immense! The old formula I always heard

during my weaving days (here where most handweaving was other than pile

knotting) was that it required five spinners to keep one weaver furnished with

yarn, and it required five carders to keep one spinner supplied with roving

ready to spin! Now, when we see “hand spinners” in Turkey, for example, anyone

who has prepared and processed their own fleeces is giddy: those Turkish village

spinners invariably have nice neat rolls of uniform machine carded roving ready

to go! Even if they have their own sheep, those spinners now can take their wool

to town where it can be run through carding machines.

Richard,

Re “technical” matters: If it’s possible to make generalizations, I

think it’s fair to say that usually the more “primitive” the equipment, the

higher the level of weaving skill required. Our fancy jack and contra-marche

looms with multiple harnesses, roller beams, and fine-toothed ratchet controls

solve many of the technical problems that inventive tribal weavers have to work

out in creative ways. In other words, it’s much easier for American “hobby

weavers” to turn out a satisfactory product than for the skilled and experienced

Asian nomad weaver with much more primitive equipment.

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 02-02-2008 09:00 PM:

Let's see, where did I leave my horse?

Marla,

Oh, great. Now I need a horse, too. And 25 carders and

spinners.

That

certainly explains why we see a lot of younger girls and older women spinning

wool in their spare time. So it would be ready when they had the time for

weaving.

Then the more experienced girls and women do the weaving. Your

explanation certainly puts the process into proper perspective. And it also

explains to some extent why many families kept the best of their weavings for

many generations.

I have a lot more appreciation now for the tribal trappings

that are hanging around the house.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Martin Andersen on 02-03-2008 04:04 AM:

Hi All

Just putting some numbers on Marla Mallett's 1:5:5 formula.

Regarding a fictive main carpet that could be 4 months weaving, 20 months

spinning, 100 months carding. That's a 124 months working time just with the

basic weaving and the wool. Then clearly the rugs must have been extreme luxury

objects in their time of production. Our own culture certainly doesn't produce

many artistic objects involving a time like that

regards Martin

Posted by Steve Price on 02-03-2008 06:28 AM:

Hi Martin

Marla's formula translates to 1 weaver + 5 spinners + 25

carders. That places the weaver's labor contribution at about 3% of the total. I

can't help wondering about the accuracy of what she was told. It doesn't seem

reasonable to me; although that doesn't prove much.

Also, it was for

flatwoven textiles, not for pile. Inserting, tying and cutting knots is all in

addition to and very much slower than running warps back and forth across the

loom. I don't know the extent to which it changes the relative amounts of time

taken for the various labor inputs, but it has to be a significant increase in

weaver time relative to the others.

Hi Sue

Vis-a-vis your 1850s

Tekke torba: color me skeptical. It's less than two weeks since you revealed

that Turkmen carpets were designed for the tribespeople by by classically

trained mathematicians and only a day or two since you told all of us about a

20% elastic recoil when tentbands were relieved of the tension they had on the

loom. And those two are just what's still on the active discussions.

Steve Price

Posted by Martin Andersen on 02-03-2008 07:08 AM:

Hi Steve

Your are right. The flat weave contra the pile weave of

course must change the ratio, and be lowering the total time of production. I

will stop trying to figure it out. Its not rocket science, but its complicated

Someone with valid

practical experience should be able to give a rather precise estimate.

Someone with valid

practical experience should be able to give a rather precise estimate.

Regards Martin

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 02-03-2008 09:16 AM:

Hi all,

Aside from simple observation (try to stretch a tent band),

some consideration of function will lend additional creedence to Marla's

statements regarding excessive stretching, which I think would be no more than

about 1-2 percent under a load.

Most of these items were constructed for

light industrial use, and their properties were well known to both users and

creators. The technology fitting a requirement for long narrow morphology with

significant elastic behavior under long axis stress has been know for eons; it

is called rope. Specifically, laid rope - rope made of twisted plied strands of

twisted plied strands.

The stretching property of laid rope is the basis

of its heavy use on sailing ships - the masts and sails required limited amounts

of free motion, with the property of returning to their original geometry when

the stress was removed from the system.

However, that same property also

has been a headache for users of laid rope for eons. The component materials are

not perfectly elastic - some of the stretch becomes permanent. Laid rope

elongates over time and eventually breaks as the component strands fail.

Handling heavy materials with laid rope has always been a problem precisely

because of its resonant elastic behavior - stuff starts to bounce.

That

elastic behavior is sometimes helpful for mountain climbers who take a fall -

ropes that do not stretch (modern, "kernmantle" climbing ropes stretch far less

than laid rope) will snap your back. But I can tell you from personal experience

that laid rope can stretch too much while accomodating a long fall and you can

still hit the local hard flat spot - several times - as you bounce around wating

for the rope to cease its elastic behavior.

One would certainly want to

get away from such elastic behavior when attaching enormous overloaded sacks of

grain, and/or huge mafrashes, to camels and donkeys. Otherwise, your stuff would

be falling off the animal at inconvenient moments. And yurts are designed to

accomodate elastic requirements with the frame, not the frame constraint bands.

Stretchy bands = house collapsing on your head.

I own several of each

type of band, and I observe the same things Steve does - these bands would fail

long before a 5-10 percent stretch is accomodated.

Regards,

Chuck

Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-03-2008 11:32 AM:

Please don’t worry too much over my carding-to-spinning-to-weaving ratio and

take it too seriously. It would NOT apply to pile-rug knotting. It would apply,

roughly, to production of the plain-weave, striped weft-faced rugs that fill so

many Turkish, Kurdish and Persian village houses—the ubiquitous furnishing

objects that most collectors never see, pieces that rarely reach the

marketplace. I mentioned the old saw mainly to emphasize the part of the textile

production process that most people aren’t even aware of. In Western and Central

Asia, often an entire family is involved in the wool preparation processes. Work

on the loom is the tip of the iceberg—the part that’s relative “fun.” Wool

cleaning, sorting, and carding or combing is pure drudgery, spinning a bit more

enjoyable, but still time consuming. As I mentioned, in recent years, as carding

machines became available, the whole process was shortened immeasurably. I must

admit that I don’t know when that option became available to nomads or villagers

in various places.

Marla

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 02-03-2008 11:44 AM:

tent bands

Chuck,

You probably know that those fishing nets, due, in part, to

their morphology, would roll up side to side and be useless in the water if

there was no compensation made for the forces they had to overcome built into

their design--as I recall they were hawser-laid. Is there any evidence of an

equivalent design compensation in your tent band selvages? I guess it could be

called hawser-plyed. Sue

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 02-03-2008 01:04 PM:

Hi Sue,

In fact, the bands don't have much of a selvage at all. My

Qashqai malbands (camel/horse/donkey packstraps) have a more decorative than

functionally constraining selvage. The Uzbek and Turkoman bands have

none.

And, none of them exhibit much of a tendency to curl - either at

the edges, or across the width of the band as a whole.

Here is a link to

thread in an archived Salon by Fred Mushkat - my bands are toward the bottom.

Note that the malbands appear to have weft yarn that is much thicker than the

warp yarns - this may have a significant contribution to do with lateral

stability.

Fred Thread

Regards,

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-03-2008 07:36 PM:

Sue,

I just read your notes describing the warps in your Tekke torba, and

wonder why that kind of object is relevant to a discussion of mixed technique

tent bands and the kind of looms used for them. I presume that it is your

professed concern about "broken warps." For me, a Tekke torba is not an

appropriate comparison, for the following reasons:

1. The warp yarns for

warp-faced, mixed technique tent bands are heavier, more substantial yarns, spun

to provide a satisfactory warp-faced surface as well as to provide the strength

of a sturdy tent girth.

2. Roughly twice as many warps are crowded into

the same width: a range of 18 to 28 warps per inch is typical for a Tekke torba

or mafrash, while around twice that many are used in a typical Tekke tent band

(usually fewer in Yomut and other bands).

3. The knotting is spread out

over at least twice as many warps in the tent band: i.e. with a torba of 24

warps per horizontal inch, there are 12 knots tied on those warps per horizontal

inch--a knot on every pair of warps. On the tent band, knots are tied only on

ALTERNATE warps (because they are tied only on the top layer of warps, with a

shed open). In other words, for every 48 warps per horizontal inch, there are

only 12 knots per horizontal inch.

4. On the tent band, knots are tied on

different sets of warps in successive rows. Thus in areas of solid pile, only

half of the warps are used.

5. On most of the mixed technique tent bands,

usually less than half of the surface is knotted pile. In the older bands, far

more than half of the surface area tends to be open plain weave or

brocading.

5. When constructing any knotted-pile piece, including a

knotted pile torba, the most stress on the warp yarns occurs NOT with the

changing of the sheds, but with the knotting process itself--the constant poking

of the weavers' fingers into the warp, the grasping of those warps and pulling

them forward in pairs to wrap them with the pile yarns and then tugging on the

pile yarns to tighten the knots. When the number of knots tied on each pair of

warps is reduced significantly as in the mixed-technique tent bands, and the

pile areas are scattered about, there is obviously much less wear and tear on

the warps--and significantly less potential damage. The work is much faster, as

well.

Marla

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 02-04-2008 01:07 PM:

Chuck,

Thanks, but your bands and these Turkmen ones with pile are whole

different animals. I'm sorry if my post of the cardwoven band confused. I meant

just to show that unused warp could be wrapped up. Your other loom woven band is

way different, too.

Marla,

Thanks for the added structural info. If

I'm understanding it correctly, the tent bands were double warped, with 2 warps

to each heddle loop. One of the sheds within a shed you spoke of was used to

separate the paired warp yarns where knots were not needed. The pairs would stay

together, with the shed within a shed unused, in areas where pile knots were

needed. This would account for too many thicker warps than should fit, and also

the odd look of the warps from the back.

But if that is the case, wouldn't

there have been some sort of twill patterning shed within a shed, for wefts

used, either in front of or above the bands, to keep the separated warp pairs in

the none pile areas, on the front of the bands, orderly? Sue

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-04-2008 07:37 PM:

Sue,

No, the tent bands are not "double warped with 2 warps to each

heddle loop." Each warp needs to operate separately.

What I have called

a "shed within a shed" is the way that virtually all West and Central Asian

carpet looms are set to operate. A ground loom setup for a band with knotted

pile can operate in this same fashion, and indeed, the Goklan weaver in my

website photo appears to be set up in this way. Alternately, such a loom can

operate with a heddle bar that lifts as apparently is the case in the Shahsevan

loom photo. The basic difference is that in a carpet-loom setup the heddles form

a primary shed that is held open permanently, while the shed stick moves to a

position within the heddle space to open a secondary shed. (This kind of

setup--for both vertical and ground loom setups--are diagramed in my book on

page 25.) In either case, with the mixed technique bands, knots are tied WITH A

SHED OPEN, ON JUST THE RAISED WARPS. The knotting arrangements for these bands

are explained on a website page: www.marlamallett.com/bands-htm . This seemingly odd

construction allows for twice the number of warps to give a band extra

strength.

On the back of a mixed technique tent band, we can identify

EACH warp position, although sometimes not clearly: Each warp is either enclosed

by a pile yarn or it lies BEHIND a knot in the pile sections. In the plain-weave

areas we see every separate warp.

I was careless and misspoke when in my

initial remarks I said that four different sheds were needed for the

pile/flatweave bands. I had in mind some of the more complex warp-patterned

bands and jajims that are made with the same kind of staked-to-the ground loom

set-up. The flat-weave/pile bands use just two sheds, but display knots tied on

FOUR DIFFERENT SETS OF WARP PAIRS. The all-pile bands are constructed just like

a pile carpet, thus are inferior in terms of practical use. It's not surprising

that they are more rare.

Marla

Posted by Marla Mallett on 02-04-2008 07:50 PM:

Let me correct one sentence in the above, in my description of the back of

the pile/flatweave bands: Each warp is either enclosed by a pile yarn or it lies

BEHIND or BETWEEN a knot in the pile sections.

Marla

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 02-05-2008 12:52 PM:

Marla,

OK. Now I get it, two sheds. So what I thought was warp

shrinkage behind the knotted pile areas was just warp displacement which would

have been there on the loom. And the thinning of the wefts behind the knotted

areas is just due to stretching from the knots being beaten in.

So then, if

I'm getting it right now, these bands have much in common with Chuck's warp

faced band except in the knotted pile areas. If warps broke their repair ends

could be hidden easily in the shed with the weft. And, there would have been

less tension on the loom than I was envisioning.

Then, still just assuming I

get it, not only would a horizontal ground loom be good enough, but the time

these bands spent on the loom would be drastically less than what I was thinking

it would be.

This aha/duh moment has an additional bonus for me. I can use

those extra sheds I thought I'd be needing and put them to work in my project's

unpiled areas for a little bit of subtle warp patterning duty. It's starting to

sound fun again. So, thanks again. Sue

Posted by Jim Allen on 02-06-2008 01:38 PM:

Qualitative Limits

There are limits to warp tension imposed by the tensile strength of hand spun

woolen warp threads and their length. As I understand it the upper limits of