Posted by R. John Howe on 09-22-2006 08:39 AM:

Classical 16th-17th Century Persian Rug Fragments at the TM

Pieces of a Puzzle

Classical Persian Rug Fragments from Khorasan

Daniel Walker, TM Director and exhibition curator

September 1, 2006 through January 7, 2007

Daniel Walker has curated a second exhibition at Washington, D.C.’s Textile

Museum since his appointment last year as the Museum’s director. Fitting, nicely,

into one of the upstairs galleries at the TM, this exhibition offers nine fragments

of Persian Khorasan carpets all, with one exception, estimated to have been

woven during the 16th and 17th centuries.

Walker conducted a “walk-through” of this exhibition on Saturday, September

16, 2006. What follows is my write-up of my notes taken during it and another,

a week earlier, by a member of the TM curatorial staff.

(I am also indebted to the TM and especially to Cyndi Bohlin, its Communications

and Marketing manager, for the images, gallery labels and press release. I have

used all three in what follows.)

Walker said at the start of his walk-through that there are several things indicated

by the “Pieces of a Puzzle” title of this exhibition.

First, since the exhibited fragments came from larger pieces, a degree of reassembly

may be possible. Many of the designs in these fragments are repeats. This permits

at least graphic reconstruction of larger areas. We may be able to glimpse a

bit of what the whole likely was. Second, these fragments all come from one

area of historic Iran, Khorasan.

A further general meaning of the title is that the fact that the pieces are

fragments of manageable sizes permits comparisons among them that are more feasible,

certainly more convenient, than would be the case between the whole rugs some

of which were arguably of gigantic palace size.

`

Additionally, it is sometimes possible to learn things from a fragment that

are important for puzzling out some aspect of the whole (about which more below).

Walker added that these fragments are also undeniably beautiful in their own

right despite their fragmentary and often worn condition. They can still command

our aesthetic attention.

It might be good to begin by listing the indicators that suggest that all of

these pieces were woven in historic, Persian Khorasan [the area indicated on

the TM map includes areas now in Pakistan and Turkmenistan (including in the

latter case, Merv)].

Khorasan indicators include:

o Use of the jufti knot in larger areas of a single color

(two versions of the jufti were used both asymmetric,

open left)

o Use of lac red (but also used in India in the same time

period)

o Outlining in red

o Use of distinctive orange and a blue-green

The use of the jufti knot is particularly distinctive since this usage in Khorasan

seems to be traditional and not employed, as in other areas of Iran, as a labor-saving

strategy.

Walker made the point that in the period of interest Khorasan was a very large

area. It contained at least four major weaving centers. Some variation in usage

should be expected. Not every piece will have all of the Khorasan indicators.

Note: In what follows I will in each case present an image of one of the fragments

immediately followed by the TM’s caption for it.

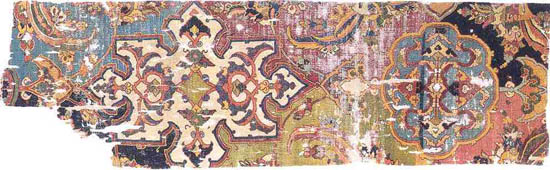

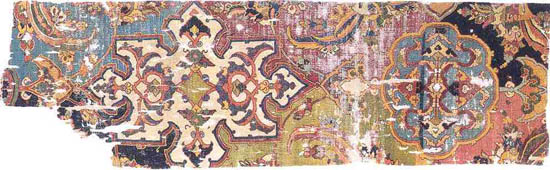

The first piece, Walker drew attention to, is one of two 16th century fragments

in the exhibition.

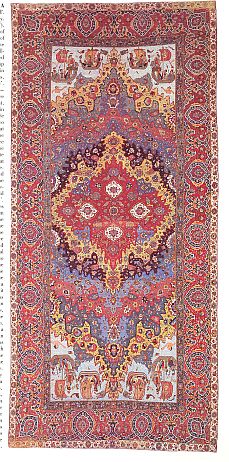

Image caption:

Fragment of a carpet with compartment

design

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period

2nd half of the 16th century

knotted pile; wool, cotton, silk

The Metropolitan Museum of Art,

Fletcher Fund, 1991

A little closer look at one of the medallions on this piece.

It was purchased by Martin, the famous collector and rug book author, in Istanbul

in 1898 together with another fragment from this same rug. It appears in Martin’s

book. The second fragment from this rug was apparently sold in Europe. This

one went to a private collector.

Walker knew of it when he was at the Cincinnati museum and got it there on extended

loan. He got permission to take it with him when he moved to the NYC Metropolitan

and when the owner decided to sell it, it was purchased by the Met. It is here

on loan (as are eight of the pieces in this exhibition).

Walker said that we know this piece is 16th century primarily because of the

style of drawing on it. It has complex blossoms and sickle leaf forms that are

of an identifiable Persian style employed in the second half of the 16th century.

And many of its devices have framing outlines, sometimes in as many as four

colors. This is a typical Khorasan usage.

Interestingly, the weaver changed the ground colors used in this piece from

one area to another, increasing the complexity of the design.

The warp is cotton and the wefts alternate between wool and silk (not intertwined).

We will see that the other 16th century piece in this exhibition was arguably

made for a Turkish client, but this piece has a definite Persian style throughout.

It was purchased by Martin in Istanbul and might have traveled there as an ambassadorial

gift (such gifts from Iran to Ottoman Turkey are documented for the period in

question).

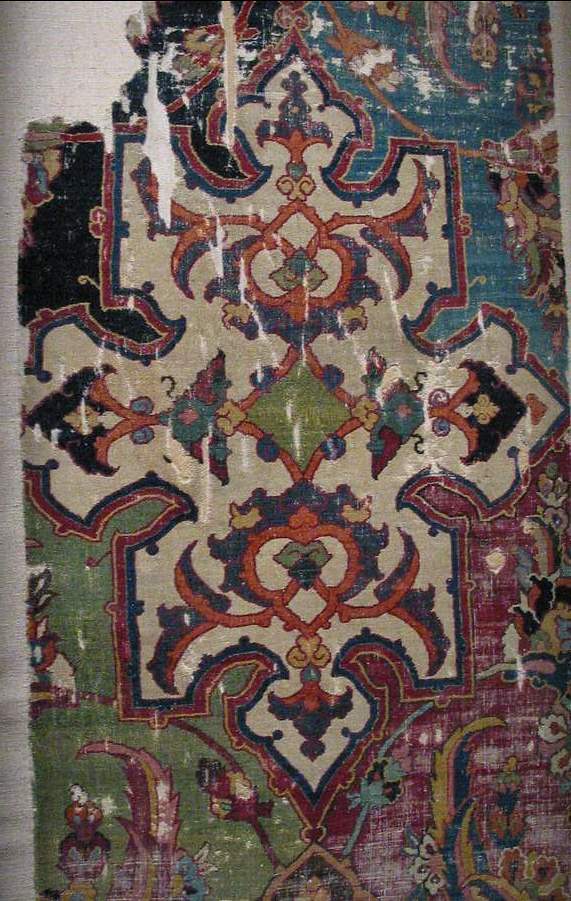

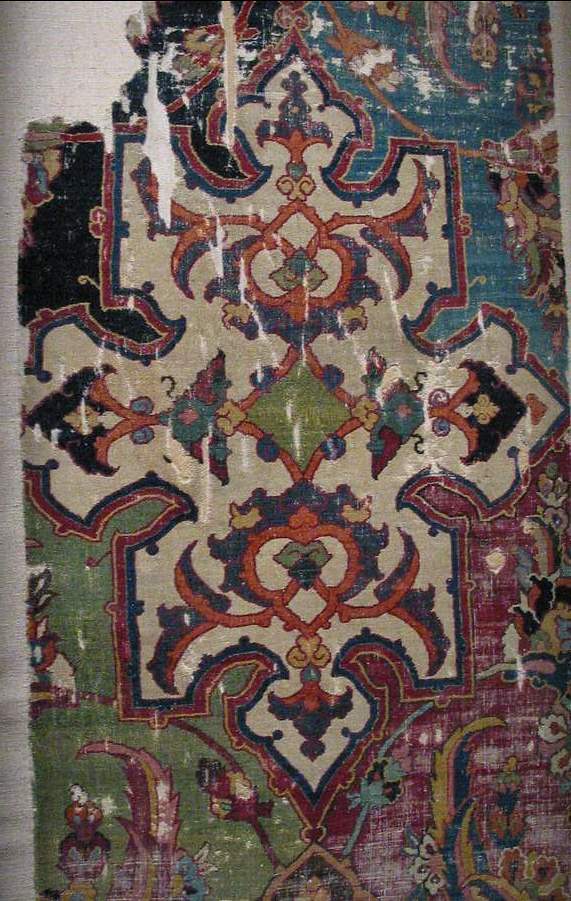

Walker walked into the exhibition to treat the second 16th century example that

is presented in three fragments that fit together.

Image caption:

Fragment of a multiple-medallion

carpet

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period

2nd half of the 16th century

knotted pile; wool, cotton, silk

The Textile Museum R63.00.17

Acquired by George Hewitt Myers in 1956

This first fragment, of a three-part assemblage, displays part of the field

on which medallions are placed in a spacious way on a red ground. On the right

there is a strip of border.

A second field fragment (below) is scalloped on its top edge in a way that exactly

matches that on the lower end of the TM piece (it’s difficult to see because

this fragment is attached to a red backing).

Caption:

Fragment of a multiple-

medallion carpet

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period

2nd half of the 16th century

knotted pile; wool, cotton, silk

Collection of Marshall and

Marilyn R. Wolf

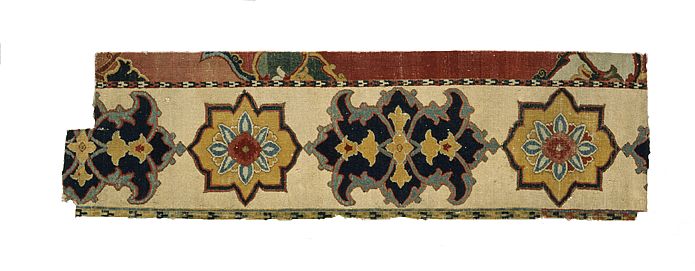

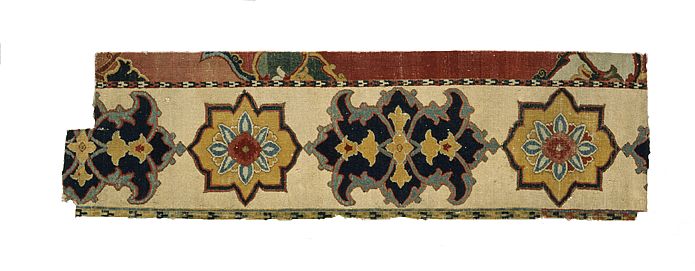

The third fragment (below) is a border only (in some ways the most spectacular

piece in the exhibition) that fits perfectly into the lower end of the border

on the TM piece and is clearly the border for the right hand side of the second

field-design-only piece.

Caption:

Fragment of a multiple-

medallion carpet

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period

2nd half of the 16th century

knotted pile; wool, cotton, silk

The Metropolitan Museum of

Art, The Page & Otto Marx Jr.

Foundation Gift and Rogers

Fund, 2001

This assemblage has all of the Khorasan indicators, but is Turkish rather than

Persian in the “feel” of its spacious red field embellished with occasional

medallions.

The second, field only, fragment in this assemblage has another feature that

suggests strongly what the large piece was like. The left side has no border

but close examination has revealed that it is finished (that is, the wefts circle

the far left warps and return). This raises the question of why is there no

border on such a finished side. More, some medallion forms that occur on the

left side of this piece are exactly half of full medallions that appear further

out in the field. This has led to the suggestion that this largish fragment

is part of one panel of a very large “palace-type” carpet made in multiple panels

to be fit together to decorate a very large space. The reason for making such

palace rugs in panels is likely that no single loom could accommodate the size

needed.

This Persian Khorasan rug seems likely to have been made on order for a Turkish

customer.

Walker treated the three of the four 17th century pieces in the exhibit together,

but also separately.

He said they are all repeat patterns, but each one is different. In some cases

there are borders but one of them is field only. Two are lattice designs, one

is a sickle-leaf field only.

The first of the lattice design fragments is perhaps the vaguest of the pieces

in the exhibition.

Caption:

Fragment of a carpet with

lattice pattern

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period, 17th century

knotted pile; wool and cotton

Private collection

Despite lost of wear and bare white cotton wefts getting fuzzy, it has some

wonderful colors and drawing.

The second lattice design fragment is larger. It is one of two fragments from

this rug, the other residing in a German museum.

Fragment of a carpet with

lattice pattern

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period, 17th century

knotted pile; wool and cotton

Private collection

Walker noted that its drawing is a little stiffer than that of the 16th century

pieces. But the range of color and complexity of devices is still visible. I

thought that one yellow palmette at its center top is a possible antecedent

to the central devices in the “eagle Kazak.”

Walker said that this piece has been lost for twenty years, but appeared at

auction recently, was recognized by a few, purchased and will join its mate

in the German museum after this exhibition.

The sickle-leaf field design fragment is only the only fragment of this piece

known.

Caption:

Fragment of a carpet with

sickle-leaf design

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period, 17th century

knotted pile; wool and cotton

Private collection

It has a green ground and despite being 17th century retains the curvilinear

drawing of the previous century.

The remaining 17th century fragment is a “tree” design.

Caption:

Fragment of a carpet with

tree design

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Safavid Period, 17th century

knotted pile; wool and cotton

Private collection

This piece has branches some with flowers and others with fruit on them. One

branch has recognizable pomegranates.

The last piece is 19th century and has a different look altogether.

Caption:

Carpet fragment

Iran or Afghanistan

Khorasan Province

Early 19th century

knotted pile; wool and cotton

Lent by H.M. Keshishian

This fragment is composed almost entirely of borders. It has a different palette,

mostly red and blue, and shows some real conventionalization, primarily that

the border designs are butted rather than resolved. Walker described it as baroque,

even roccoco. Despite its lateness, this piece exhibits some clear Khorasan

features. It is has areas of jufti knotting, red outlining, some lac red and

the characteristic Khorasan orange. Moreover, it is known, independently of

these indicators, that the piece from which this fragment was taken was woven

in Khorasan in about 1820.

Toward the end of this walk-through Walker commented that sometimes rugs as

old as those in this exhibition are more accessible by price than one might

think. One of the 17th century pieces in this exhibition was purchased recently

at auction for approximately the price of a small, new car.

Walker has burgeoning duties as the TM’s director, but one is grateful that

he has been able to justify curating two recent TM exhibitions. He is likely

one of the few people in the world who could identify this important group of

pieces and manage to assemble them side by side in one place.

This exhibition will be an important feature of the upcoming Textile Museum

symposium to be held October 20-22, 2006.

Details of the symposium are available on The Textile Museum's site at: http://www.textilemuseum.org/symposium.htm

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-22-2006 12:13 PM:

Resolved vs Butted Borders

Dear folks -

As I reported above, Dan Walker, emphasized the "butted" borders on the 19th

century Khorasan fragment as one indicator of conventionalization in its design.

I meant to ask him, but the questions from others became too numerous for me

to intrude without displaying bad manners, whether there are some older Khorasan

pieces that include resolved borders.

His comment would seem to indicate that there are.

I have noticed butted borders on some otherwise quite sophisticated pieces.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-22-2006 10:01 PM:

"Portugese" Carpet Fragment

Dear folks -

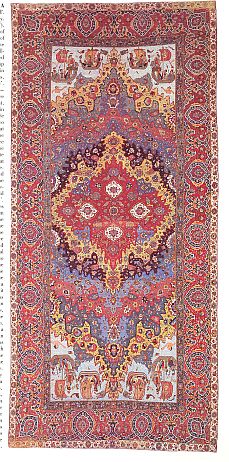

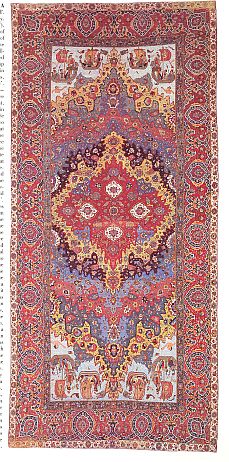

As one enters this exhibition the first Khorasan carpet fragment is on the right.

And one is facing a panel on which a rug very similar to the one below (it may

be the same piece) is printed.

The image above is taken from Hali, 31, page 15 and is captioned there as:

The Vienna "Portugese" Carpet

Khorasan, possibly Herat

late 16th century

3.13 x 6.80m (10'3" x 22'4")

The reason for this juxtaposition is that this first fragment is from such a

rug, historically called a "Portugese" rug, in part in ignorance of the the

characteristics of Khorasan weaving, but also because the spandrels contain

pictorial areas on which there are sailing ships and human figures.

Not only are the figures in western dress, but Charles Ellis (who analyzed the

known existing examples of the Portugese rug group) suggests that the ships

resemble Portugese caravels.

An alert person in the walk-through group asked, why such scenes should be displayed

on Khorasan rugs, since this area is entirely land-locked.

Walker responded that the Khorasan area was on the path of frequent trade and

that these scenes may well have been encountered on, and copied from, such things

as 16th century maps which often contained similar drawings.

This first fragment is the only piece in this exhibition seen to have been part

of such a "Portugese" carpet.

To have such obvious western imagery on a 16th century Khorasan carpet demonstrates

that western influence has been visible in Persian rug design for a very long

time.

Different subject: this Portugese carpet is also an example of a Khorasan carpet

with resolved borders and thus answers my question about that above.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Stephen Louw on 09-23-2006 01:33 AM:

Dear John - thanks for a wonderful presentation, appreciated especially by

those without ready access to the TM. I enjoyed your last comment about western

influences on Khorasan carpets - this really brings home the fact that carpet

weaving traditions have always been as much a reflection of long-standing often

change-resistant endogenous beliefs, customs and conceptual vocabularies; and

the ever intrusive influences of outsiders. These latter, I suspect, found a

ready audience for reasons that have as much to do with the pressures of commerce

as they do with the curiosity and creativity of the artists in question. Ships

on rugs produced by weavers in a landlocked country before the age of mechanical

production being a good case in point!

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-23-2006 09:47 AM:

Dear John,

I agree, this is a truly great post. Thanks so much for putting this together.

I like the first Khorasan carpet fragment the best. Would love to see a computer-simulated

reproduction of it. In the close-up (second image), did the black areas got

dropped accidentally? What looks like black in the first image is white in the

second.

The change of ground colors is what makes this carpet magnificent. None of the

ground colors border directly on each other even though the round and star medallions

do not seem to touch each other at first sight. And four different ground colors

must provide a satisfying contrast to each medallion.

I don’t understand the connection to the "Portugese" carpets group though. These

carpets all have similar designs, including the characteristics boats, which

is very different from the Khorasan carpet fragment above. Furthermore, I thought

the origin of these "Portugese" carpets is still very much in doubt.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-23-2006 03:06 PM:

Tim -

You said in part:

"...Would love to see a computer-simulated reproduction of it. In the close-up

(second image), did the black areas got dropped accidentally? What looks like

black in the first image is white in the second..."

Me: There is a computer simulation of the field suggested by this fragment in

the exhibition. It does not include the spandrel areas with the boats and human

figures or the borders. Perhaps this is known to be part of a "Portugese" because

some other instances have similar fields.

You also question whether it is known that "Portugese" rugs are Khorasan.

The Hali article I cited indicates that there are some rugs with these sailing

scenes that do not have Khorasan characteristics. Some of them are seen likely

to have been woven in Azerbaijan.

But the piece I have shown from Vienna has Khorasan characteristics, notably

a jufti type asymmetric knot open to the left. For Portugese rugs with this

structure there seems not much question.

Glad you and Stephen have said that you liked the post. It did take a little

effort.

Regards.

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-23-2006 03:22 PM:

Hi John,

This is not exactly what I meant. I questioned the attribution of the Khorasan

carpet fragment to the "Portugese" carpets group, as I see no connection betwen

the two. If I understand the literature correctly, the Portugese label refers

to a particular design type. The piece from Vienna surely falls into that category,

but I don't see how the Khorasan carpet fragment could.

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-23-2006 03:43 PM:

Hi Tim -

As I said in part:

This fragment "...does not include the spandrel areas with the boats and human

figures or the borders. Perhaps this is known to be part of a "Portugese" because

some other "Portugese" instances have similar fields."

I'm not sure what makes you suspicious. If you look at the image of the complete

"Portugese" carpet you can see that one could take a section out of its field

that would give little hint of its overall design, including its pictorial spandrels

or its borders.

Classical period Persian rugs from Khorasan are part of Daniel Walker's field

of scholarly specialty (look at his "Flowers Underfoot" catalog, if you want

to get a sense of his erudition within it). I doubt that he would make such

a claim without basis.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-23-2006 04:18 PM:

Hi John,

I'd also be surprised if Mr. Walker made a mistake here. However, the Khorasan

carpet fragment seems to be inconsistent with the way other rug scholars describe

the "Portugese" carpets group. It is not just the boats in the spandrels, but

also the main field design that is characteristic.

For example, Spuhler writes in his book "Oriental Carpets": "The ten to fiften

known 'Portugese' carpets form a uniform group, as they are based on the same

design concept and vary only slightly in drawing."

I found images of "Portugese" carpets (or fragments) in five of my books, and

all of them are similar to the Vienna piece. The Khorasan carpet fragment, however,

is completely different. That's why I am curious why Mr. Walker put them together.

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-23-2006 08:38 PM:

Tim -

I don't know more than I've indicated. If I have a chance to ask Dan Walker

about this, I will.

If you want to investigate further, Steve has given me the volume (left of colon),

page indications for the Hali treatments of "Portugese Carpets."

4/3: 257

31:15

34:44

46:34

61:127

68:127

72:126

89:92

108:67

114:9

114:76

119:81

I've only looked at the first two, since what I wanted was a color image of

the Vienna Carpet.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-24-2006 12:15 AM:

Hi John and Steve,

Thanks for the list of Hali references. I have only one of those issues (#61),

and scanned the image below.

.jpg)

It seems to be a right corner, and the irregularly drawn blue leafy thing at

the bottom indicates it is also of the Vienna type.

Maybe others have access to the other Hali issues and could provide scans.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-25-2006 04:09 PM:

Apparently No "Portugese" Pieces in this Exhibtion

Dear folks -

I went back the the "Piece of a Puzzle" exhibition to check what is actually

said about Portugese rugs in the gallery information.

I have to admit that Tim Adam's suspicion is well-founded. There is no claim

that any of these fragments is from a "Portugese" carpet. The references to

Portugese rugs seem entirely restricted to the panel on which the "Vienna" Portugese

example is pictured.

My error was in wrongly interpreting something that Walker said during his walk-through.

We were standing between the panel with the Vienna piece on it and the first

fragment in the exhibition and I asked Walker a question about "Portugese" carpets.

He carefully replied that this label applied "only to this one."

My mistake was to think that he was referring to the first actual fragment in

the exhibition. I think now he was likely referring to the pictured carpet only.

Sorry for the reporting error and high marks to Tim for hanging in there with

his suspicion.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-25-2006 05:03 PM:

Hi John,

This situation now reminds me of an experience I had in my Latin class back

in elementary school. I was never a good student, but once I received an A-

in an exam. The teacher returned it to me with the words, "Auch ein blindes

Huhn findet einmal ein Korn." (Even a blind chicken finds a grain once in a

while.)

Anyhow, I am glad you brought up the topic of Portugese carpets. I learned something.

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-26-2006 11:51 AM:

Dear folks -

On the "travel" board Jeff Krauss has made a post that is relevant both to his

recent travel and the pieces in this exhibition.

I have take the liberty of copying Jeff's post into this thread as well.

"I should point out that this carpet fragment in Berlin

and this fragment now on display at the TM

are evidently fragments from the same carpet, and I understand that the TM piece

will be sent to Berlin after the current exhibition closes."

Dan Walker indicated during the walk-through that what Jeff says about this

piece in the TM exhibit eventually going to join its mate in Berlin is true.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-26-2006 01:42 PM:

Hi John,

Given that there are several different fragments, and each one of them interesting

in their own right, I'd turn this thread into a salon.

Regarding the fragment of a carpet with lattice pattern from the Safavid period,

I believe it is not from the same carpet as the one in the Berlin Museum. The

two pieces are very similar, no doubt. But a few details seem inconsistent.

Take a look at the borders. They seem to have slightly different coloring schemes.

Another indicator may be the white flowers next to the large c-shaped leaves.

They are of different proportions in the two fragments.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-26-2006 08:08 PM:

Tim -

It is true that putting up a series of pieces in a linear thread has disadvantages

but I think we're stuck with that format for this one.

Coloring differences can readily be the result of different photographs, different

reproduction methods, even different monitors.

I don't know what to say about the design differences you mention, except that

these fragments seem often to be from very large carpets and there is room for

variation within them.

What Jeff and I have reported is our understanding of what has been asserted:

that these two fragments are seen to have been from a single rug and that they

will both be part of the Berlin museum's collection after the "Pieces of a Puzzle"

exhibition ends.

I think that there was indication that the piece in the TM exhibition recently

surfaced in an auction.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-26-2006 09:34 PM:

Hi John,

The TM piece was sold at Rippon Boswell last spring, and Mr. Maltzahn mentioned

during the auction that this fragment belongs to the Berlin carpet fragment.

However, I happen to know someone in the textile division of the Berliner museum,

who disagreed with this statement. Now I wonder whether the purchaser and Mr.

Walker never bothered to actually compare the two fragements closely?

The auction catalog has a much better color reproduction of the TM fragment

than the one you posted. The catalog image is also much closer in color to the

Berlin fragment. So, comparing those two images I started to get some doubt,

because I also agree with you that in large carpets there is room for variation.

However, another thought occured to me about the total length of the carpet.

The Berlin fragment is already 4 meters long. Given the design of the TM fragment

and preserving symmetry of the overall design, I think the total length would

have to roughly double to 8 meters. That sounds a bit large, although not impossible.

The V&A museum also has a carpet of this design. Maybe the TM fragment belongs

to that one? Anyhow, I find this detective work fascinating.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-26-2006 09:44 PM:

Hi everyone,

I just stumbled across another fragment that is almost identical to the Khorasan

carpet fragment shown above. The color reproduction is much different, however.

It's from Spuhler "Oriental Carpets", plate 75, and attributed to the 1st half

of the 16th century. Spuhler writes that it is likley from Central Persia (Kashan

or Isfahan), but South Persia is also possible.

Tim

Posted by Tim Adam on 09-26-2006 09:59 PM:

And as a post scriptum to the "Portugese" carpet story: Weavers in the Caucasus

have copied the Portugese design. Here is an example (reduced in length) from

the Shirvan region from the late 18th century. Spuhler writes, it is further

evidence that classical Caucasian designs were based on Persian models.

Tim

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-27-2006 02:13 AM:

Hi Tim,

The fragment from "Oriental Carpets", plate 75 was exhibited at 'Le Ciel dans

un Tapis' at the Institute du Monde Arabe in Paris last years. Its reproduction

is also used as the cover of the Exhibition’s catalog (and it’s also in the

book, plate 33).

That reproduction is also much darker of the plate you present; if you want

I can scan it so you can compare the colors.

Louis Dubreuil visited “Le Ciel dans un tapis” and kindly sent me some photos.

There’s also a close-up of that fragment. Here it is, rotated of 90 degrees.

The colors rendition in Louis’ picture are in the middle between your scan and

the catalog. Once again, it shows that typographic reproduction must not be

taken as necessarily faithful to the original.

Regards,

Filiberto

P.S. This fragment belongs to the Berlin Museum für Islamische Kunst and it

was bought by F.R. Martin as well, in 1898. So, this is the second fragment

mentioned by Walker as "apparently sold in Europe."

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-27-2006 07:42 AM:

Dear folks -

Good research on finding some of these other pieces and the information provided

about them.

Just to be clear, all of the images I have presented from this exhibition, excepting

the one of the "Vienna" Portugese rug, are not from scans that I made but from

a CD that the TM kindly sent me.

It seems to me that there is some variation in the colors in these images as

compared to what one sees standing in front of the pieces in the exhibition,

but the images the TM has provided me come from some very carefully taken photographs.

There are lots of potential sources of color difference between the TM negatives

and what appears on your monitor (e.g., the TM CD images were very large and

in TIFF format and had to be resized), but none of these originate in my scanning.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-27-2006 06:42 PM:

Am I to take it that it's R.I.P. for structural analysis? What's happened?

Was it but a passing fad in rugdom--gone before even the most primary things

about textile structures were learned adequately by most? That seems to be the

trend, doesn't it? Why? I don't get it. Sue

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-28-2006 01:26 AM:

You are absolutely right, Sue.

This is the structural analysis provided by the catalog of 'Le Ciel dans un

Tapis' for plate #33:

Warps: white cotton Z4S

Wefts: white or yellowish silk, three shots

Knots: wool (Z) asymmetric Persian knot, some jufti knots, 1224 knots/dm2

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-28-2006 02:47 PM:

Thank you, Filliberto.

According to the TM's blurb on their website technical analysis of textiles

has been in use since the 1970s. If the TM takes the subject seriously enough

to tout it in their own description of this exhibit shouldn't the results of

their endeavors in this regard be considered noteworthy enough to be printed

in their descriptions? After all, it is they themselves who point out that this

particular approach has led to significant advances in recent years. Is the

strange lack of technical analysis of the exhibited fragments simply a correctable

mistake? Did these "most significant" puzzle pieces just fall on the floor unnoticed?

If so can they be retrieved and given the prominence we are told they are worthy

of?

As things stand I am sure I am not alone in being left to wonder if there is

anyone at the NYC Met or the TM qualified to utilize and record the results

of these "new" analysis skills on these fragments which have come into their

hands. If the structural analysis of these exhibited fragments has been undertaken

beyond the level of descriptions of what might be expected of placards at a

children's petting zoo should not this information be most prominently displayed?

It will be interesting to see if any technical analysis of substance will be

forthcoming now that what I will assume are but crucial overlooked boo-boos

at the TM have been pointed out here. I hope the TM PR people are on their toes

on this one. We shall see what we shall see. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-28-2006 03:22 PM:

Hi Sue

I disagree. I don't see any more reason to include the technical details of

carpets (or carpet fragments) exhibited in a museum than there is to include

comparable technical details on, say, French impressionist paintings, Japanese

screens, or medieval European armor in museum exhibitions.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-28-2006 04:11 PM:

Hi Steve,

What you or I think on the subject of structural analysis has no bearing whatever

on the point I am making. I think your and my vastly different ideas on the

subject have coloured your perception of what I have said and therein lies your

misunderstanding of that. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-28-2006 05:13 PM:

Hi Sue

I must have misunderstood your last post. When you said, If the TM takes

the subject seriously enough to tout it in their own description of this exhibit

shouldn't the results of their endeavors in this regard be considered noteworthy

enough to be printed in their descriptions?, I interpreted it to mean that

you were objecting to the fact that structural detail was not included in the

descriptions on each rug in the exhibition. Now that I know that this wasn't

your meaning, what is it that you meant?

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 09-29-2006 01:04 AM:

Hi Steve,

Why was structural analysis touted as a useful tool in the TM blurb for this

exhibit? There clearly is no evidence it was used. Can you not tell that from

the descriptions? The descriptions given are unenlightening and worse than some

I've seen printed earlier than the those from the 1970s. It is in this manner

the TM leaves the whole idea of structural analysis to dangle in a void as if

knowledge in rug studies is going backwards and not advancing. From what they

say in the exhibit blurb the impression it seems they were trying to make is

that rug studies are advancing. This purpose is not well served by such careless

handling of the subject in the descriptions. If they are serious they can correct

this. Do you understand the concept now? Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 09-29-2006 06:05 AM:

Hi Sue

You wrote, ... your and my vastly different ideas on the subject have coloured

your perception of what I have said and therein lies your misunderstanding of

that.

We obviously have different ideas about what constitutes a reasonable description

for an object on display in a museum. But my understanding of your previous

post - that you were disappointed that the TM didn't include structural analysis

in the labels in this exhibition - was correct. It appears that we have a difference

of opinion, and that it isn't based on my failure to understand your words.

Such things happen.

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-29-2006 08:35 AM:

Dear folks -

I think Sue's criticism is that detailed structural analysis of each piece is

not included in the gallery labels for "Piece of a Puzzle" exhibition.

I'm not sure why that is the case, although all but one of these fragments was

borrowed and that information needed to be conveyed.

I do know that Walker was VERY familiar with the structural details in these

pieces.

I think the decision not to give great structural detail might have been based

on the fact that the basic structure in these pieces is the same. They all use

one of two versions of a "jufti" asymmetric knot open to the left in areas of

a single color. There is, in fact, in one part of the exhibition, a panel that

shows drawings of these two jufti knot variations as compared to more usual

"over two warps" version. So that structure is very explicitly treated.

And if you look closely at my report on the first fragement you will see that

at one point in his walk-through Walker notes that "the warp is cotton and the

wefts alternate between wool and silk (not intertwined)," clearly indicating

that he is closely familiar with the technical details in these pieces.

And in my summary of Khorasan characteristics that Walker reported is not just

the use of the jufti knot but of lac dyes for red areas. Lac was also used in

India, but not with the jufti structure.

So there are clear indications both in the exhibition and in Walker's walk-through

comments that structural and other technical features of these fragments were

not neglected.

I think Sue's complaint is that they are not reported piece by piece in the

gallery labels as they are sometimes in rug books. Even there one sometimes

sees omissions (for example most writings on Kurdish weaving give warps and

wefts and color pallette and design but omit knot after a summary mention because

use of the symmetric knot is general).

Sue is right that the technical details of these pieces are not reported in

the gallery labels, but her inference that this suggests that structural and

technical concerns have been jettisoned moves too quickly to that conclusion.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sue Zimmeran on 09-30-2006 04:14 PM:

These fragments speak more to me of the ever perennial tradition of low end

mass marketed production than any other tradition. While I could expound on

why this is until the cows come home I don't think anyone cares to read about

that from me so I will contain myself on the subject unless there is any serious

interest expressed. Sue

Posted by Jeff Krauss on 09-30-2006 04:51 PM:

quote:

Originally posted by Tim Adam

The auction catalog has a much better color reproduction of the TM fragment

than the one you posted. The catalog image is also much closer in color to the

Berlin fragment.

After looking at the TM piece this morning, I agree that the image from the TM

web site is too cold (blue-greenish tint) and the real color is closer to the

warmer color I captured in my (flash-less) photo from berlin.

Posted by Steve Price on 10-01-2006 06:17 AM:

Good Morning, All

I just blocked a post in the moderator queue for its ad hominem content.

As with all posts blocked for this reason, the complete text is available to

anyone upon request. The writer agrees with Sue's belief that the structural

details provided in the exhibition labels are inadequate for the viewer's understanding

of these carpet fragments.

The style and content initially led me to believe that the author was Cassin,

but now I doubt it. The "exhibition" of Turkmen trappings on his co-called weaving

art museum includes no structural information at all; he obviously sees this

issue the same way I do.

Anyway, I add this in order to let everyone know that Sue's position on the

inclusion of structural details in exhibition labels has some supporters. The

author was silent about whether the pieces are examples of low end mass marketed

production, another point on which Sue and I see things differently.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-01-2006 07:24 AM:

Dear folks -

Walker made clear that "commericial" influences are visible in these 16th-17th

century fragments. The clear "Turkish" feel of the large red-ground piece and

the boats and human figures in western dress are two such indicators.

Walker also said that the Persian Khorasan carpets are the last Persian group

to be studied closely and there may well be things still to be learned about

them.

But to jump quickly to a conclusion that what the rug scholarship to date suggest

is erroneous (simply because the technical information is not included on the

gallery labels) seems a pretty large generalization and would need some basis

of its own.

Walker gave some clear indicators that are used to suggest that these piece

were (excepting the one 19th century fragment) woven in the 16th and 17th centuries.

I don't think I want to hear Sue go on for hours about anything but she owes

a serious curatorial effort like this more than her own impressionistic response.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-01-2006 07:31 AM:

Hi John

Just a word or two to clarify my previous post. When I said that I disagreed

with calling the pieces in this exhibition low end mass marketed production,

my disagreement is primarily with the words low end (what was the high

end?), secondarily with the words mass marketed (were these sold in 16th/17th

century Wal-Mart or Ikea?).

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-01-2006 10:36 AM:

I think the Vienna "Portuguese" carpet is a perfect example that commercial

weavings should not necessarily be frowned upon. The central design reminds

me of a super nova, and the amount of life and movement in this carpet is incredible.

It's a real masterpiece.

Maybe what matters is the skill of the weaver (that’s for sure) and the sophistication

of the client.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-03-2006 05:52 PM:

Of course, the other commercial piece, the multiple-medallion carpet with a

Turkish feel, is breathtaking too. It would be great if someone could put the

three fragments together and produce a computer image of the whole thing. Would

this be possible in Photoshop, or would one need more specialized software?

John, to test the "no single loom could accommodate the size needed"- hypothesis,

it would be useful to know the dimensions of these fragments. Is this info available?

Do you know of any Persian or Turkish analogs to this carpet?

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Richard Larkin on 10-03-2006 06:04 PM:

You say low end, I say high end

Folks:

Low end, high end, commercial, I don't know anything about that stuff. I will

say that I always took the the people in the boats to be sort of goofy, non

sequiturs, as it were. Or I should say Goofy, as it seemed like putting

him, or Mickey Mouse, into the rug. Just one man's impression.

Wonderful thread, John, as usual.

__________________

Rich Larkin

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-04-2006 04:23 AM:

Commercial or not commercial may have a meaning when we speak about

tribal weaving, not in this context.

These pieces were obviously made in workshops, were very expensive and were

made to sell. The only non-commercial instance (as not-made-for-sale) I can

think about are the products of workshops working for the Shah’s Court.

In any case, the people who made these pieces weren’t working on their own,

they were employees, so what’s the difference? The carpets were made for other

people anyway.

When Walker speaks about “commercial” influence I guess he means the adaptation

of design to Western specification and taste for export to the West - as opposite

to the use of a more local style and taste.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-04-2006 07:17 AM:

Tim -

As you can see in the gallery labels no measurements of these fragments are

provided.

I do think the "complete" width of the red-ground fragment with the medallions

and a "Turkish" feel to it can be measured pretty accurately.

The top of it is this piece which has a border on the right.

The next piece fits into it in a precise way indicated by the steps on its lower

right and the top right of this second piece.

This second piece is the one with traces of a finished selvege on its left side.

So the width from the right hand border on the top piece to the finished selvege

on the second one could be measured.

I do not know what loom width limits existed in the 16th century or whether

there are other instances of such "multi-panel" pieces but there are in the

literature stories of very large pieces indeed.

I don't think Walker said what maximum loom width might have been when this

piece was made. His comment about loom width was more in the context of offering

an explanation for why a piece like this might have a border on one side and

a finished selvege without a border on the other. This selveged but borderless

side interrupts the field pattern at precisely the halfway point in some of

the field medallions providing another possible hint of multiple panels of this

type.

Filiberto et al -

I am not sure that Walker actually used the word "commerical," but he did indicate

that he felt the Portugese rugs were made for sale and that the red ground fragment

was a Persian Khorasan rug likely made for a Turkish customer since the "feel"

of its design is Turkish rather than Persian. So the clear sense of commercial

was there in his remarks.

Murray Eiland has, of course, argued for years that the "commercial/non-commercial

distinction cannot be made with any reliability and he seems not to exclude

more "tribal" weaving from that claim.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-05-2006 01:04 PM:

Hi John,

If the left side of the second fragment has traces of a finished selvedge, shouldn't

the left side of the first fragment have the same? Would you remember roughly

the width of the first fragment from when you saw it at the TM?

Filiberto, I agree that if you look at specific periods and carpet types that

the distinction between commercial / non-commercial doesn't make sense, as more

or less everything was woven for sale. But I think it also makes sense to look

at commercial products over time. And there we can witness a tremendous decline

in quality. The question is why? Is it because the weaving skills mysteriously

declined, or is it because clients became less sophisticated (my previous point),

or is it because economic thinking became increasingly important so that the

cost did not justify the product?

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-05-2006 03:10 PM:

Hi Tim -

The two larger pieces of the red-ground carpet (there is also a separate border

piece that fits in on the right side) seem approximately the same width when

viewed.

It is only on the second (lower) piece that this partial selvege finish apparently

remains. (I don't think you can get close enough to look at it but I'll look

next time I'm in the gallery.)

My own sense of why commerical pressures began to affect quality is that this

began to occur once cost became a concern.

In traditional societies, time is often not seen or experienced in the terms

that we now see it.

In his account of his long stay among the Turkmen at the Merv oasis, O'Donovan

talks about the his experience trying to get the Turkmen to talk about historical

events. He found that they could not estimate historical time very accurately.

Similarly, many time-intensive modes in traditional societies were unavoidable.

There were no alternative ways of doing some of them. But once time and cost

become real concerns, and if an alternative way to do something emerges (e.g.,

synthetic dyes), then historical qualitative aspects gives way.

It seems likely that some of this has happened in every age. If you recall the

arguments of the Met curator, whose book I bought, he and his peers felt that

there was a great dimunition in the quality of rugs produced after the 17th

century.

But there are very complex fabrics (two sets of warps and elaborate looms and

multiple weavers) made in Italy, Ottoman Turkey and Persia in the period from

the 14th through the 17th century that were not economic to continue to make

once princely patrons stopped buying.

That happened once in 15th century Persia when one Shah became devout and shunned

the artistic world. One effect of that was that some skilled Persians returned

with an exiled Mughal leader to India and helped establish a formidable Mughal

textile tradition.

Nowadays, we often hear the artistry of 18th century rugs extolled and some

see a real "cliff" of quality about the middle of the 19th century. This, of

course, coincides with industrialization and the rise of machine methods.

Until about 1830 high quality furniture in the U.S. (and elsewhere as well)

had to be constructed with "hand-methods." But about then machines began to

affect things such as the fastenings, the carvings, the thickness of veneers,

even the more basic construction. You can still buy a shield-back Heppelwhite

style chair made with 18th century tools, but it will cost you about what a

similar 18th century chair would. You can do a lot better on price with modern

furniture, but often have to give up quite basic things....like wood. That's

what making time and cost central (and the develpment of new methods) have done

to quality.

But you knew all this.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-05-2006 06:05 PM:

Hi John,

Having been through the exhibition with Dan myself, I recall this:

On lower 2 feet or so of the left side of the larger fragment, the selvedge

remains intact. It is simply missing from the upper portion of the left side

and is missing entirely from the right sides of the field fragments as well

as the separate border fragment.

It is possible that the selvedge represent the center of what would have been

a large carpet pattern consisting of two pieces laid alongside one another.

It is also possible that there was once a third width section or even a fourth.

We don’t know the size of the area that was covered by these pieces. Dan’s belief

is that no loom was wide enough to produce a rug to cover the intended area.

Thus, sections were woven almost like wall to wall carpet.

It is unknown whether the one attractive border is the primary or a secondary

border. However appealing it may be, its scale is small for the size of the

rug, so it may have been secondary. The small guard border warrants comment

in another thread.

Wendel

Posted by Jack Williams on 10-05-2006 08:53 PM:

commercial decline

One point of the book I read, "The root of the Wild Madder," was this...commericial

pressure started when rugs were still woven "in the wild." However, the selling

and marketing of rugs was usually a man's job, whereas the weaving and creation

was a part of a womans life.

When men returned from the marketplace and started telling women what was selling

and what kind of rug was needed to sell, market forces were injected into the

woman's creativity. The rug being woven was no longer a mystical part of a woman.

Posted by Steve Price on 10-05-2006 10:58 PM:

Hi Jack

With all due respects to the author, the notion that in days of yore a rug that

she had woven was a mystical part of a woman seems like a romanticized view

of an unknown history.

The hypothesis that the woman's mystical connection to the rugs she wove was

destroyed when men discovered that rugs could be converted into money (and,

I suppose, from that into guns and horses and other immoral and repressive manly

things) sounds like feminist zealotry. It's probably closer to the truth to

believe that women did the weaving because it was yet another productive activity

that they could pursue while conducting the affairs that were gender-specific

to females in the society, of which bearing and caring for children was probably

high on the list.

We have some anthropologists and sociologists who participate; perhaps they

can clarify this issue.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-06-2006 02:30 AM:

Hi Jack,

Better don’t mix the concept we have about tribal/rustic production with city/workshop

production.

In the first we know that the weaver decided the design (sometimes copying or

reinterpreting it from outside sources) and at least some of the production

was intended for the weaver’s own use.

In the latter weavers worked generally on cartoons prepared by specialized artists

and the production was either for a specific client or for the market in general.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-07-2006 11:32 AM:

Hi John,

I fully agree when you write, "But once time and cost become real concerns,

and if an alternative way to do something emerges (e.g., synthetic dyes), then

historical qualitative aspects gives way. It seems likely that some of this

has happened in every age." Some altruistic person comes along and creates

a new product/idea/etc., which, over time, is copied for purely economic reasons.

The inevitable decline in quality ensues. Economic thinking can never produce

art – a downfall of economics.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Jack Williams on 10-07-2006 12:02 PM:

true

Steve and Filiberto:

True...the author of the book that I mentioned was speaking about a nomadic-tribal

product, not village or workshop weavings which were market oriented early on...

...that book is worth reading if you can get past the "author is such a wimp"

undertone. The author traveled extensively in Persia and west Afganistan in

the 2002-2003 time period...and writes about rugs, weavings, weavers, dyes,

changing sociology etc., in a crummy mealy-mouthed manner, but manages to covey

a surprising amount of fresh information from an area that has been relatively

off limits to western rug affcianados for 25 years.

His observations about the current state tribal products, manufacture, sociolgy,

etc., of is especially interesting, including Turkmen, Baluch, Khorrasan area,

and QuasQuai.

I also would like to comment on how the western view of what is "beautiful"

and "collectible" changes with time. The line of this post is unusual in that

it is about the only line I've seen that deals with classical persian-ornate

palace-type rugs. Just about everything else has been tribal-nomadic oriented

with the most praised items being those thought to be the most authentic tribal-nomadic

(often confused with being a function of age).

I have the distinct impression that 100 years ago, collecting tribal rugs was

somewhat quaint. These were regarded as crude and utilitarian while true "collectors"

were after the abridil carpet type weaving, incredibly complex, with many colors,

exact symetry, ornate.

Now, however, who on this board looks twice at a sufi-influenced, Ishfahan curvilenear

medalion symetric perfect weaving, regardless of intricacy? If such a rug were

presented for comment here, a loud silence would follow...

......or the usual trolls would be popping off with pseudo knowledgable one-liners,

sniping about bad dyes (it is almost an absolute that even experts cannot accurately

distinquish a chemical dye yellow from a natural dyed yellow, in person much

less from pictures...many natural yellows being quite "loud") It is amusing

to me to see so many people who think that to be seen as an expert, they have

to pan about everything posted, even if they are uninformed about that genre.

Or they default to posting comparisons with some totally dissimilar rug that

they happen to own.

The preception of "beauty" in rugs has probably changed significantly in the

west...just as it did in paintings when impressionism was introduced. But what

may not have changed that much is how nomads view "beauty" in their own rugs.

I see this disconnect on here fairly frequently...especially in those with little

feel for what a compartively basic life style entails. This is where the book

I mentioned can be enlightening. The view of what constitues artistic worth

from a yurt may not translate very well into a 21st century, suburban backyard

patio, good-scotch afternoon salon...

...Which may be why so many garish bad products are being mass produced...the

"producers" cannot quite understand what the western view of "beauty" is now,

and have abandoned certain endearing qualities of their own heritage in pursuit

of western commerciality.

Perhaps I ought to write a review of that book. I find myself being influenced

by the content of it...despite initially being put off by the tone.

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-07-2006 01:19 PM:

I find Jack William's between-the-lines attacks on the people of this discussion

board unbearable. Since his last post also does not have much to do with the

17th century classical carpet fragments discussed in this thread, I suggest

to move his comments to a new thread.

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 10-07-2006 02:17 PM:

Hi Tim

Perhaps I'm a little slow and insensitive, but I don't see any attacks on our

participants in Jack's post, while I do see one in yours. Folks, you don't have

to like each other, but you do have to tolerate each other on this forum.

Jack, if there were digs at others that I just missed, please be a good guy

and stop doing it.

Also, to Jack: I'm guessing that the author of the book has a name, even if

it's just a pen name. I think the author's name is a relevant piece of information,

although his personality is rarely as interesting or important to us as the

book's contents.

Thanks

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-07-2006 02:44 PM:

Hi Steve,

I thought it is relatively obvious, but here are the phrases I had in mind.

......or the usual trolls would be popping off with pseudo knowledgable one-liners,

sniping about bad dyes ...

It is amusing to me to see so many people who think that to be seen as an expert,

they have to pan about everything posted, even if they are uninformed about

that genre.

The view of what constitues artistic worth from a yurt may not translate very

well into a 21st century, suburban backyard patio, good-scotch afternoon salon...

The first two refer to Jack's previous experiences on this discussion board,

while the third characterizes Turkotek in general, in my opinion.

Tim

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-07-2006 03:39 PM:

Hi Tim.

You bring up an interesting, close to home, point when you say "Economic thinking

can never produce art--a downfall of economics".

My father majored in economics in grad school but used all that to eventually

own and run companies some of which were advertising agencies in the East and

Midwest. Having me, an artist, as a daughter was a major problem for him from

the time I was very young. He thought I would be doomed without his intervention.

He was probably right.

The gist of the thought behind his incessant training was a view, from the other

side, sort of, of what you say and can be boiled down somewhat to "Artists are

notoriously incompetent at business and marketing. If you are going to be an

artist you MUST learn the principles behind business and the skills for dealing

with what manifests from that quarter. Knowing these factors and their inextricably

linkage with art were not optional for me, in other words, and I actually grew

to enjoy learning about economics and business related stuff as much as learning

about art. This is mainly why this Khorisan production caught my attention.

It seems a most striking example of big business genius at work I've not read

about but knew must have existed since I first looked in on rugs. My assessment

and curiosity leading to further research was based more on the glimpse into

the times afforded by Persian miniatures more than rugdom's, quite frankly,

because the brains in artdom at the time were based in court and beyond rugdom's,

it seemed, and seems still, to me, invisible bullet proof glass doorless walls.

What looks to me like a well oiled almost turnkey business machine with a footprint

spanning about a third of Persia is breathtakingly awesome way beyond the scope

of what remains of the products manufactured there.

There are some people I think would appreciate such things as much as I do and

I'd like to point some things out to them. But, unfortunately for me, they are

all long dead. Hopefully someone will pick up the trail in the future. I've

got other plans. Sue

Posted by Steve Price on 10-07-2006 04:14 PM:

Hi Tim

Sorry, but an ad hominem remark has to be much more direct than that

to exceed our limits.

Having said that, let me add, for Jack's benefit: Those of our participants

who irritate you will be here for as long as they choose to be (as long as they

remain civil).

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-07-2006 04:44 PM:

Sorry, Steve. I think you completely misunderstood what I wrote. I have never

said that Jack made ad hominem remarks, rather that he made "between-the-lines

attacks on people." I have also not asked for any sort of censoring him, as

your last post seems to imply. I have merely stated my irritation with his remarks,

and suggested to move his post to a new thread as it has little to do with the

subject at hand. -- Tim

Posted by Jack Williams on 10-08-2006 02:07 AM:

information on the book

Steve et. al.

The Root of Wild Madder: ...Chasing the History, Mystery and Lore

of the Persian Carpet (ISBN: 0743264193) by Brian Murphy, Simon & Schuster,

2005.

I thought I had previously posted the reference to this book in this line. My

mistake, I must have posted it elsewhere. From this book came an extensive quote

about an Afgan refugee, his family's carpet woven by his grandmother, the guls

that were woven into it, why it was important to him, and his willingness to

part with it for dire need, that I posted in another line.

As I said, I was initially a bit put off by the tone. But I found myself checking

it out of the library a second and third time, finding more interesting eyewitness

information and observations on the carpet craft in Iran each time I read it.

Because he poor-mouths his carpet knowledge, I may have discounted his commentary

the first time. It is worth the read

I believe my comments were germaine to this line and were a summary of some

thoughts that have been germanating for a while. They were not directed at an

individual, but at a certain style of posting that often seemed to me to ignore

some important points of nomadic-tribal society and carpets, in favor of western

collector values. It was intended to be a comment on artistic interpretation,

which was a subject under discussion.

Posted by Steve Price on 10-08-2006 09:08 AM:

Hi Jack

Thanks for the followup info on the book. Looks like a good read.

I understand that there are people on this forum who irritate you; there are

some that irritate me, and every participant probably has a little list of folks

who'd never be missed if they vanished from our boards. But public expressions

of frustration will sometimes generate responses from the people who are irritated

by you. In the end, they accomplish nothing, bring latent hostility to the fore,

and can lead to situations in which Filiberto and I are forced to referee duels.

Neither of us wants to add that to our list of (unpaid) tasks. For this reason,

I ask that you keep your annoyances to yourself or use private e-mails to transmit

them.

Tim, I'm sorry for misunderstanding what you were trying to say. The subject

of topic wandering comes up fairly often, and we generally put up with it as

long as it isn't terribly abrupt, since it's part of normal conversation.

Thanks

Steve Price

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 10-08-2006 02:03 PM:

Hi Jack, and Everyone,

In today's world amongst my serious professional female artist peers who, at

times, sell to the public face to face, I cannot recall any conversation touching

on anything like the notion "art as a mystical part of a woman".

Of course my circles are not the only ones. I have overheard conversations,

engaged in by people who's work can be described as "decorator stuff", discussing

what industry has deemed to be the next season's hot colors but that is because

their livelihood depends on using them. They know that their work won't sell

on it's own merits. I realize this might sound egotistical but it really isn't.

Just as within any profession it is generally known by pretty much everyone

who are the artists in the field and who are the mechanics.

If you add to what Filiberto has posted to you on the subject, which is accurate,

that is how it still is today if you change his word "cartoon" to "after a fashion"

or, in the ever less polite but real artspeak, "plagiarized hack work" I don't

see things as having changed much other than in that the "cartoons" were probably

paid for.

At the risk of some readers taking offense I'm going to tell it like it is for

those who would like to know. Those who's work falls in, let's say, politely,

the "mechanic" category love opportunities to speak about their work. Anthropologists,

sociologists, gallery guys, the press, or whoever comes along with a notepad

and pencil. This is not the case with real artists.

The visual artists I know, and have known, and count myself and am counted amongst,

would rather face a squadron of ET's fully armed with high-tech laser beam surgical

equipment approaching their sanctuary than anthropologists, sociologists, gallery

guys, or the press making their way towards the door. I'm not kidding. Sue

Posted by Tim Adam on 10-09-2006 12:08 AM:

Wendel mentioned that the small guard borders of the Khorasan fragments with

the "Turkish look" deserve comment. As a reminder, here is the fragment again.

I'd agree that the choice of this type of guard border looks odd, and I was

looking for analogs in the literature, but couldn't find anything. Wendel, did

you have a particular comment in mind?

However, in my search I came across another fragment that has a very similar

design as the one here: a blue medallion on a plain red ground (Spuhler: Oriental

Carpets, plate 127). The main difference is that the medallion is wider horizontally,

which might suggest that it is from a different carpet. An interesting piece

of information, however, is that Spuhler attributes this piece to India.

Regards,

Tim

.jpg)