Posted by R. John Howe on 08-13-2006 11:22 AM:

Oriental Rug Aesthetics in 1910

Dear folks –

For most of my early life, until age 12, I lived in a

very small town in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna Valley, Avis by name. Going to

school we used to walk by a small, white clapboard Church of Christ one block

off Main Street.

Two weeks ago while traveling I discovered that this

church has, for no reason I can discern, become a sizable used book store full

of shelves 10 feet tall. In it I paid a little too much for an interesting rug

book.

Its simple cover belies the contents of this volume. It is a

“Catalogue of a Loan Exhibition of Early Oriental Rugs” that opened in New York

City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art late in 1910. Its 41-page introduction was

written by Wilhelm Valentiner, then the “Met’s” Curator of Decorative Arts. My

copy is one of 1,000 printed.

Mr. Valentiner’s views seem likely to

represent those of those who saw themselves as the foremost experts on oriental

rugs at this time. He says some interesting things.

First, he says that

the exhibition had to draw on loaned rugs mostly in private hands because in

1910 “no institution in this country has as yet a collection of old rugs equal

in any way to the collections in nearly every large European museum, especially

those of London, Paris, Berlin and Lyons.” The Textile Museum here in

Washington, D.C. was not to be founded for another 15 years.

http://www.textilemuseum.org/about/history.htm

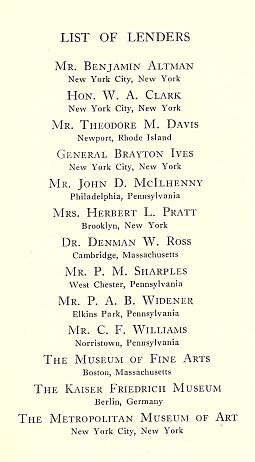

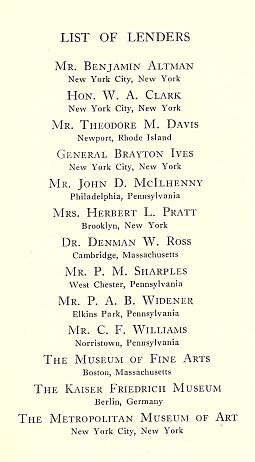

The list

of lenders to this 1910 "Met" exhibition contains some names with which many of

us are familiar.

Second, Mr. Valentiner has strong views about what rugs are

“worthy” of consideration by folks serious about them. Here are a few passages

(they are too good not to quote at length):

He says (and claims that

Bode, Martin and Sarre agree with him) that “three centuries are especially

distinguished by their excellence in rug weaving, namely, the fifteenth,

sixteenth and seventeenth.” Valentiner says that the “superiority” of the rugs

of these centuries is “distinguished by their infinite varieties of pattern,

their clarity of design and wonderfully rich harmonies of color.”

Sadly,

Valentiner goes on, the superiority of 15th, 16th and 17th century weaving “is

not yet recognized by the educated public.” They seem not to see that “seemingly

old types such as Ghiordes, Ladik, Meles, Kula, Bokara and other fabrics which,

as a rule, are not older than 1750 and usually show a lack of clearness in

design and a weak sense of color relations typical of periods of

decadence.”

I love "decadence." A real rug world "swear word," signaling

something likely more general and even worse than

"degeneration."

Valentiner quotes Martin on this point: “It is

incomprehensible that collectors who know splendid oriental carpets can be so

fond of such poor work as the Ghiordes and Kula carpets which one sees now in

almost every collection.”

Valentiner allows that there may be some 18th

and 19th century rugs that might serve as “appropriate and charming floor

decoration, but they never stand comparison with those made in the earlier

periods.”

He goes on “The eighteenth and nineteenth century rugs of

different manufacturies repeat the same pattern over and over again; a pattern

which is generally a misunderstood imitation of a design of the sixteen or

seventeenth century, and one that has often lost the meaning of the older

conventionalization of natural forms. Every old rug, on the contrary, has a

marked individual character showing a design that has never been exactly

repeated and is alive with the personal quality of every great work of art. In

more modern types it is seldom possible to determine the meaning of a single

motive, to know whether flowers, animal forms or purely geometric designs were

intended. It is even difficult to decide which is the ground and which is the

pattern, and in what connection the border stands to the centre field, or, in

fact, even where the border begins. The pattern is always overcrowded, lacking

in the noble simplicity which is characteristic of the old rugs as it is of all

really great works of art. And the modern color-schemes are as restless as the

designs; they lack the power and sobriety of the old rugs of the fifteenth and

sixteenth centuries or the subtlety and delicacy of such fabrics of the

seventeenth century as the so-called Polish carpets.”

Valentiner and his

fellows are particularly exercised about collectors choosing eighteenth and

nineteenth century rugs over older, more worth worthy ones because “It is seldom

a question of price, as the sums paid for Ghiordies rugs and other weaves of the

late eighteenth and early nineteen centuries are often greater than those paid

for good Asia Minor rugs of the fifteenth and sixteen centuries, which belong to

a period of the highest artistic feeling.”

So such purchases were not

only aesthetically impoverished, they were financially inexcusable as

well.

Now it is hard not to smile at these words since in 2006, rugs

woven in the 19th century are the center of those seen as worthy of collection

and a collector who owns a rug that was demonstrably woven in the 18th century

is likely display that fact in a prominent way. But a late 19th century rug was

essentially “new” in 1910 and fifteenth, sixteenth and seventeenth century rugs

were, apparently, not only available, but priced (if Valentiner is to be

believed) at levels accessible to those who could buy a Ghiordies at that

time.

But is seems clear that the arguments being made by Valentiner and

his fellows are mostly aesthetic and are very similar to those being made

nowadays to distinguish pieces woven in the 20th century from the more

meritorious ones now said to have been woven in the eighteenth and first half of

the nineteenth century. This similarity demonstrates to me again how subjective,

or at least socially constructed, the aesthetic values of a given age seem to be

and make me smile about the certainty with which many experienced folks in the

rug world believe that they (and perhaps only they) have “a good eye.”

I

am not sure we will want to pursue this issue much in this thread, but one could

attempt to collect some images of rugs from the 15th, 16th and 17th centuries

and to compare them with similar pieces from the 18th and 19th centuries to see

if we can discern the differences that so exercised Mr. Valentiner and his peer

experts in 1910. The catalog itself provides some 50 examples, but they are all

in black and white photographs.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 08-13-2006 12:29 PM:

Hi John,

Thanks for demonstrating what the French say: plus que ça

change, plus que c'est la même chose.

On the other hand, I wonder how

good my collection will be considered in a couple of centuries.

Well, let’s

make three centuries, to be on the safe side.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Tim Adam on 08-13-2006 06:19 PM:

Hi John,

Thanks for posting excerpts from this book. Fascinating! And

the comparisons you suggested are very worth while, in my opinion. Some of my

books I purchased exactly for this exercise. I am not sure, however, if I agree

with your conclusion.

quote:

But is seems clear that the arguments being made by Valentiner and his fellows

are mostly aesthetic and are very similar to those being made nowadays to

distinguish pieces woven in the 20th century from the more meritorious ones

now said to have been woven in the eighteenth and first half of the nineteenth

century. This similarity demonstrates to me again how subjective, or at least

socially constructed, the aesthetic values of a given age seem to be ...

Design deterioration is a continuous process into the 20th

century. It doesn't stop in the late 19th century. Or, maybe I misunderstand

your point.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-13-2006 07:52 PM:

Hi Tim -

I would not hold that there is not such a thing as an ugly

rug or that conventionalization cannot be noted and evaluated.

What I

object to is the seeming conviction by Mr. Valentiner and his peer experts that

they have discerned the basis for determining what rugs have aesthetic

merit.

Take conventionalization, for example. Sometimes (often?) it can

have results that are not pleasing, but not always. Jerry Silverman spoke up

recently about a Caucasian rug precisely to indicate that, for him, the

conventionalization of the design elements had moved to a very lean position

indeed. His seemingly approving description suggested that, for him at least,

there can be Mondrian-like versions of some rug designs that are very

pleasing.

My own take on Valentiner and his expert peers is that they

seemed to be "hooked" generally on "old" and are insisting, not always

consistently, that there was a kind of aesthetic "cliff" in about the 18th

century and the world of rugs went roughly to hell then, and that the only

viable solution is to go back to the "golden" years of the 15th, 16th and 17th

centuries.

Now it is easy, and a bit unfair, to pick on their language,

so I am going to take the assertion of Valentiner and his expert peers seriously

and put up images of some of the sorts of pieces they seem to recommend (I have

also found at least one example of a dreaded Kula). This may permit others to

offer counter examples from later periods that they feel have real merit in the

aesthetic world.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-13-2006 08:36 PM:

Hi John:

I think I understand that you are going to post some excerpts

from the catalog. Excellent. It seems that some of the reasons for which

Valentiner damned the 19th century rugs, e. g., ammbiguity between what is

background and what is design, or the repetition of motives where the original

design was forgotten, are some of the reasons for which connoisseurs today prize

the same rugs.

Given Valentiner's comments, are there any rugs shown in

the catalog that you were surprised to find there? Anything we would today call

13th or 14th centuries, or earlier? Seldjuk, as contrasted with

Ottoman?

By the way, I see him invoking the term "decoration," to be

contrasted, presumably, with "art." The use of the phrase, "decorative carpets,"

usually damning them with faint praise in order to exalt "artistic" carpets, was

always a pet irritation of mine.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Tim_Adam on 08-13-2006 11:10 PM:

Hi John,

Is it not generally accepted among carpet scholars that the

16th and 17th centuries were the high points in carpet manufacture, which has

declined since then? Based on your quotes, I think this is basically what

Valentiner is saying.

He may be a bit too dismissive about 18th and 19th

century weavings, but if the comparison is with the most accomplished carpet

achievements he has a point I think. The reason why most collectors would

proudly show off their 18th century rugs is because the point of reference

nowadays is mostly 19th century.

The only pharse I find objectionable is,

"Every old rug, on the contrary, has a marked individual character showing a

design that has never been exactly repeated and is alive with the personal

quality of every great work of art." To say that every old rug is great is

probably a bit too strong. Similarly, it would be too strong to say that every

rug of the 18th and 19th century is inferior to older rugs, and I would expect

Valentiner would agree. I think he is talking about gerneral

tendencies.

Tim

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 07:45 AM:

Tim:

I don't suppose John has much quarrel with Valentiner's opinion

as to the superiority of the older rugs. The remarkable thing is his near

contempt for the 18th and 19th century rugs that are so prized today.

We

do have to concede Valentiner's point about the vogue of certain Turkish prayer

rugs in that time. They went on a kind of "tulip madness" binge, if I've got it

right. And I think some of the highest fliers weren't even the best examples.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-14-2006 08:17 AM:

Dear folks -

Valentiner presents and describes in this catalog rugs

from each of the centuries that he and his expert peers see as the "worthy"

ones. For the 15th century he cites rugs from "Asia Minor and Syria," this

include classical Turkish rugs and what we now call "Mamluks" from Eygpt. His

examples from the sixteen century seem to center on Persian pieces and those

from the seventeenth feature the Persian "Polish" rugs and some

Mughals.

If you look again at Valentiner's list of lenders you will see

that a Mr. Williams is among them. Williams' rugs eventually came to the

Philadelphia Museum of Art and were analyzed and published in color by Charles

Ellis. So we have some color images of rugs in the Valentiner exhibition. I will

supplement that with images I have found in other places that seem to be similar

to other rug types included in this 1910 exhibition.

And I want to

acknowledge before I begin that Valentiner and his peers have called attention

to some very beautiful rugs. My objection to their thesis is that that they seem

to suggest that there are not similiarly meritorious pieces woven after the 17th

century.

I have turned most of the following images on their sides in

order to use the shape of our monitors, but that is not the orientation in which

most of these pieces are presented when published and you may wish to print off

an occasional piece in order to see it in a more advantageous

orientation.

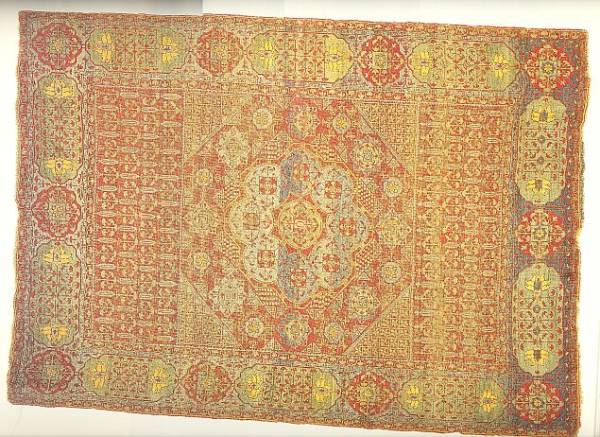

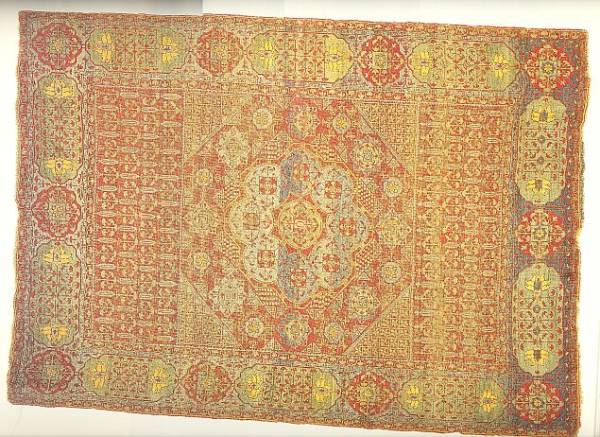

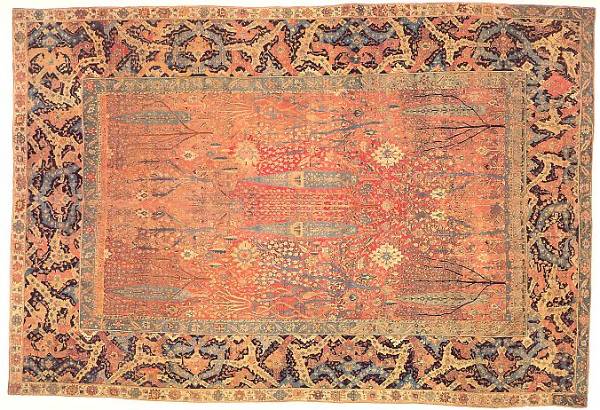

Let's start looking at 15th century rugs with a Mamluk rug

that was in this exhibition.

Despite the fact that the

Mamluks have a clear link to Central Asian they have not usually been among my

favorites. They have a narrow color palette and while their designs show great

intricacy and discipline, they often seem simultaneously busy and vague to

me.

But I think this is one of the most unusual and interesting Mamluks

of which I know. I think the variations in the design and the use of

cross-panels and cartouches is graphically very effective.

Here are some

Anatolian examples from the centuries Valentiner admired. It is not always clear

what century each of these pieces is assigned to, but they are all 17th century

or earlier. (Ellis dated some of these rugs later than they had been previously

seen to be. None of the redated rugs I will present here are seen by Ellis as

later than 17th centiry. I will not tussle with whether given rugs are 15th or

17th century, but simply include them as examples within the claimed meritorious

period.)

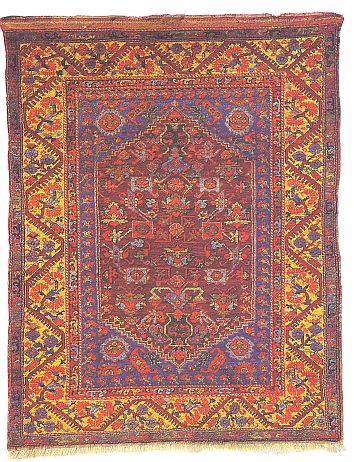

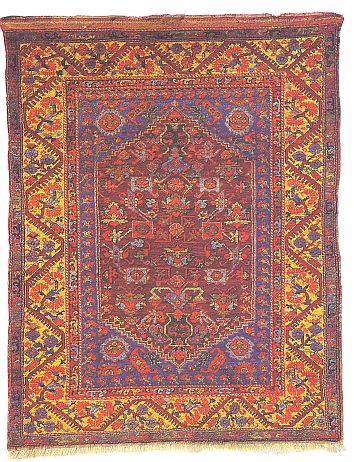

The first is a "Holbein" rug from the Williams collection that

was in the Valentiner exhibition. Ellis sees it as 17th century.

It unquestionably has

great graphics and color.

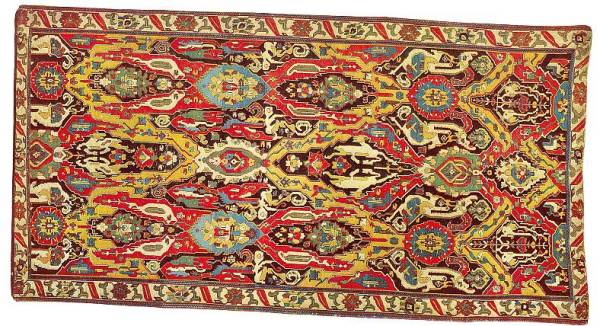

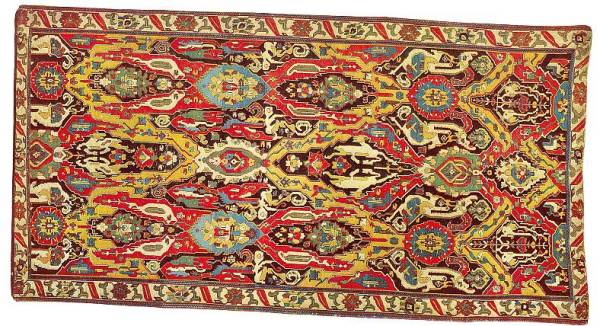

A second Analatolian piece (below) is not one

from this exhibition but is instead what we now call a "Turkish village rug,"

this one from the Christopher Alexander collection and estimated to have been

woven in Konya in the 15th century.

It has wonderful stark and

powerful graphics and a blue that has retained its vividness in an impressive

way. I think from their description of "Asian Minor" pieces from the 15th

century that Valentiner and his expert peers would admit it to their group of

worthy rugs.

The Anatolian piece below was not in this exhibition. It is

from the McMullan collection and when published was described as an "extremely

rare variant of the 'Lotto' group. (I have not included a number of the more

frequent classical Anatolian designs that could be cited as examples: the

Lottos, the momumental Usaks, etc. but have tried to give you for the most part

more unusual examples from these three centuries.)

The colors are intense and I

find the large scale of the devices in the wide borders interesting and

effective.

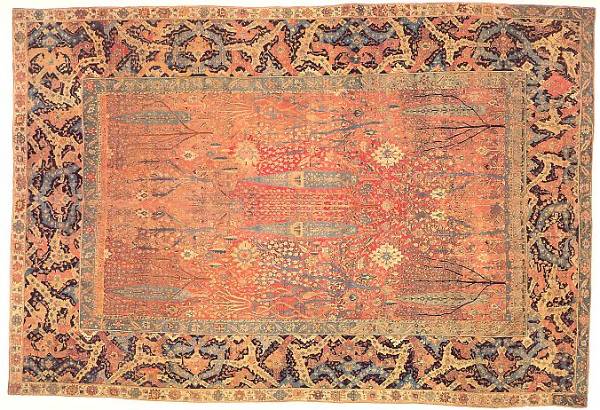

Now let's look at two Persian examples. The first, below, does

not seem to have been included in this exhibition but was part of the Williams

collection donated the the Philadephia Museum.

Ellis calls it "one of the

best known and highly respected examples of the classic era of Persian weaving

in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For me the spacious elaborateness of

the wide framing boders, the subtle, detailed drawing of the field and the very

skillful use of color make this a truly great rug.

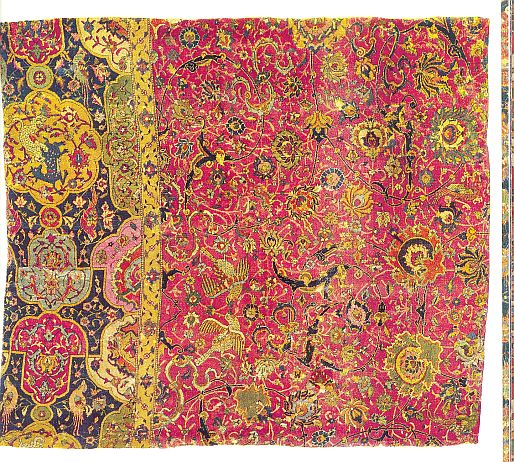

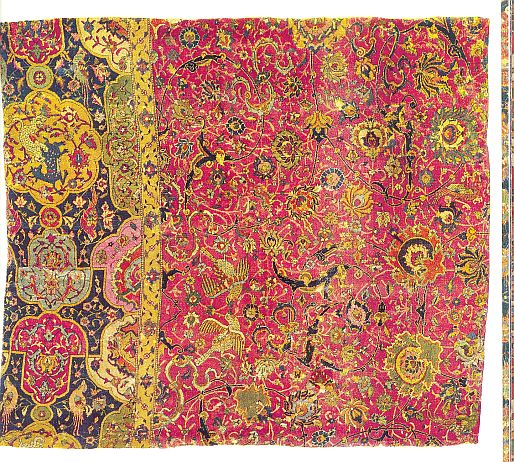

The fragment of a

classical Persian carpet below was not in this exhibition but is another that

was part of the published McMullan collection. It is described as one of the

16th century designs of the highest level of sophistication, complexity and

nervous energy" that have "survived."

Among it merits are the fact

that "The basic expression of the field is secured by placing one series of

forked arabesques over another. Either system in itself is a complete and

satisfactory design. However, the blending of two such arabesque designs is an

outstanding achievement." The description of the virtues of this piece goes on

in considerable additional detail, but despite having to acknowledge the design

virtuosity this fragment exhibits, I do not personally care for it. I find its

colors unpleasant. But it is clearly within the group that Valentiner and his

fellows recommend.

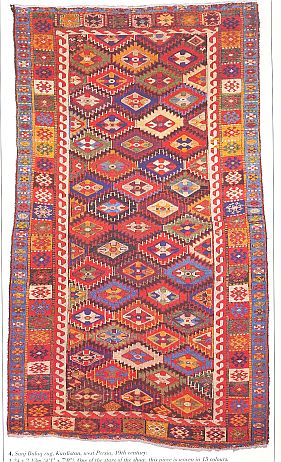

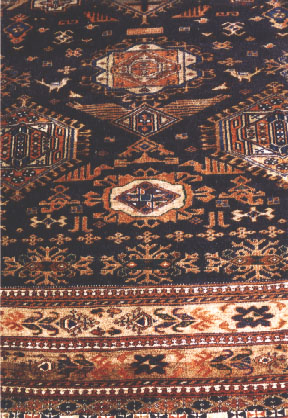

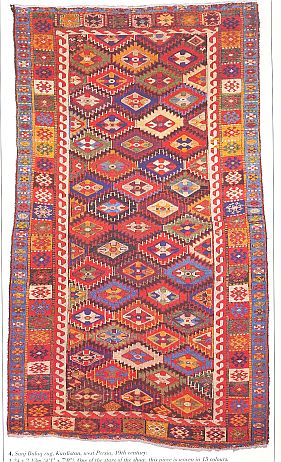

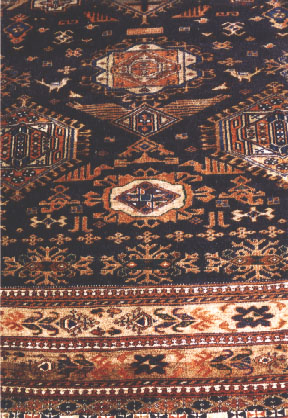

As a kind of aside, I am not sure that Valentiner and

his fellow experts would admit a Kurdish rug to their recommended group but

there were some that might meet their age criteria. The piece below is all I

could scan of a detail of another rug in the McMullan collection. The

description says that rugs with such designs were produced from the 17th through

the 19th centuries.

This is the sort of Kurdish rug that demonstrates what Kurdish

weavers are capable of with regard to adaptation of classical Persian designs

and their very talented use of saturated colors.

The last rug I want to

show you in this first series is a very dramatic example of a "Caucasian" dragon

rug. Again from the McMullan, such rugs are now dated from 17th century forward.

Valentiner did include some "dragon" rugs in this exhibition,

designating them "Armenian" and estimating them as early as 14th and 15th

century.

Now I need to consult another book or two to give you some

Mughal examples or some good Polonaise pieces, but I think you ge the idea.

These are the sorts of rugs that Valentiner and his expert peers felt should be

collected.

They are certainly objects of great beauty. My only dissent is

that I think there are things produced in the 18th and 19th centuries that are

of different, but equal aesthetic worth. This, speaking in 1910, they would not

allow.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 08-14-2006 08:36 AM:

Hi John

One thing worth bearing in mind is that these guys were

writing and collecting about 100 years ago. The 19th century stuff they saw

included the mediocre, which was most likely the vast majority (98% of the rugs

are not in the top 2% for their period). The older pieces probably had few of

the original mediocre group - they would have nearly all been

trashed.

Fast forward to today. Most of the mediocre 18th and 19th

century stuff is gone, some of the very best of it remains. So, 18th and 19th

century rugs look pretty good to us. Nearly all of the mediocre mid-to-late 20th

century pieces are still around (if you don't think so, browse eBay for a little

while). While some modern things are very good, indeed, the trash hasn't been

discarded yet. For that reason, most contemporary (say, less than 75 years old)

rugs aren't as good as most antique rugs are. But, wait 100 years or so, and the

remaining late 20th century rugs will include a small proportion of trash and a

large proportion of good stuff.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by James Blanchard on 08-14-2006 08:38 AM:

Hi all,

While I would not argue with the very general rule that "older

is better" in terms of rugs, I think that we should consider a couple of issues.

First, it would depend on which weaving groups are being compared across

time. Many of the rugs that we appreciate today are "tribal" Turkmen, Kurd,

Baluch, S. Persian, etc. Rugs from these weaving groups have developed a

following over the past several decades, in some cases rather recently. Perhaps

it is because of availability, but it might also be due to changes in aesthetic

sensibilities. In any case, based on my limited knowledge I have doubts about

whether the authors were referring to 15th to 17th century examples from these

weaving groups. Still, I think many of us still find that within these groups,

older is often better, though we seldom are able to look earlier than 150-200

years ago.

Second, I still wonder if there is a possibility of "survival

bias" in rug appreciation and collecting. Current practices suggest that many of

us are participating is the selective preservation of better examples of rugs

made in the past 75 to 150 years. For example, a pedestrian Jaf Kurd or S.

Persian bagface with poor colour is less likely to be preserved on a wall than

an exemplary version. Similarly, I expect that the relatively small percentage

of rugs that survive 200-300 years are not a representative sample of all rugs

woven in their time. Has anyone else noticed how often the versions of old rugs

that are depicted in paintings (i.e. from the 15th to 17th century) often seem

simple and uninteresting in their design and proportions (Gantzhorn is a good

reference for this)? Perhaps the painter didn't spend as much time focusing on

reproducing the rug or carpet, but if they are accurate then many of the painted

examples look like cartoons compared to the real, preserved examples. Could it

be that there were also less inspired examples of rugs and carpets woven during

those eras as well?

Just some scattered thoughts from the "peanut

gallery".

James.

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 08:59 AM:

Hi Steve,

Do you think the visible range of 19th century rug

production was significantly, or perhaps qualitatively, different in 1910 than

it was in, say, 1975 (when some of us fossils were looking around)?

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Steve Price on 08-14-2006 09:13 AM:

Hi Richard

Unless we have some reason to believe that people are just

as likely to preserve the worst as the they are to preserve the best, the

average quality of the surviving pieces from any period has to improve with

time.

So, I guess the short answer to your question is

yes.

Regards

Steve Price

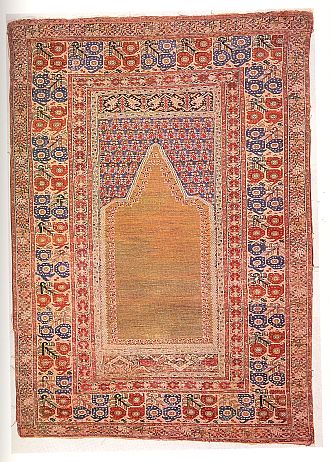

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-14-2006 10:43 AM:

Dear folks -

Two of the types of rugs that Valentiner and his expert

peers complain about collectors purchasing are the Ghiordies and Kula

varieties.

Here to give you a concrete picture of what they are talking

about are one of each of these types.

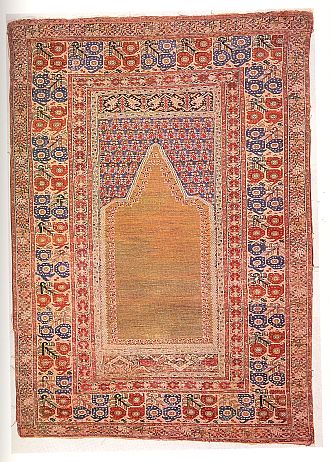

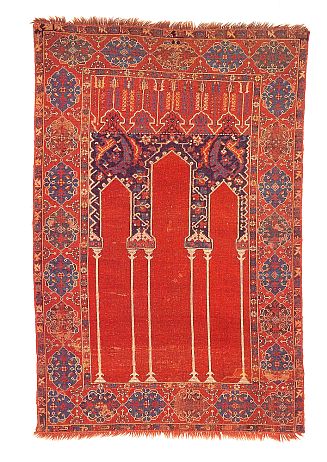

First, a Ghiordes niche format from

the Smith collection in Springfield, MA.

I heard, when I first began

to collect rugs, that there was a time when a rug collection was not considered

"complete" unless one had at least one Ghiordes. The Smith catalog referred to

above places two Ghiordes niche format pieces at the beginning of its Turkish

section.

Ironically, this is one type about which the views of

Valentiner, etc. have ultimately held sway. Ghiordes prayer rugs are not seen

nowadays as particularly desirable, although there are lots of niche format

pieces that are, for example, those in Kaffel's volume on Caucasian prayer

rugs.

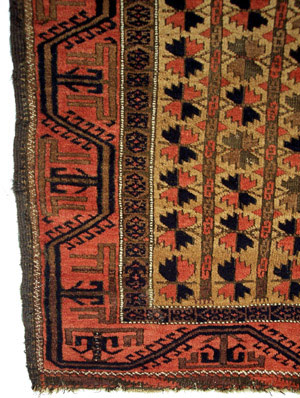

A second type objected to in 1910 was the Kula. Now in truth it may

be that the particular Kulas being pointed out then might have been those that

resembled the Ghiordes prayer rug or other niche formats with columns in their

design. Here, though, is a 19th century Kula of a different sort from a

Brausback catalog.

I personally don't find either of these pieces particuarly

attractive.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by rich larkin on 08-14-2006 12:01 PM:

rugs come and rugs go

Steve:

Of course, you're right. Still, I wonder whether the difference

as perceived at that time was such, per se, as to compel a fundamental

difference among the observers about what was worthy and what was not. I wonder

whether Valentiner was familiar with, say, what we would consider the very best

of extant Turkoman main carpets. I am thinking of something like the excellent

Yomud kepse gul carpet in the collection of the Textile Museum, or other things

of that standard. I have a feeling he was disposed at a basic level to disregard

weavings of this kind, or perhaps one should say he was indisposed to accept

them as meritorious. They would be OK to put on the floor.

As James

mentioned, we are looking at changing aesthetic sensibilities. Valentiner seems

to have been unable to take seriously certain classes of rugs his succesors in

connoisseurship now covet. I was saying in another thread that latter day New

England farmers were overlooking the artistic merit in a handmade

pitchfork.

On a side note, three cheers for the Kurdish weavers of the

world. John's example is my idea of a good looking rug.

"...[T]heir very

talented use of saturated colors." I should say so!

I was a little hurt

by his comments about the Kula, as I happen to have one. It's double or so the

length, and pretty beat up, but it's old, I own it, and there you go. (i'd put

some sort of smilie in here, but they don't seem to be available on this screen

for some reason.)

Posted by Steve Price on 08-14-2006 12:21 PM:

Hi Rich

I notice that your post indicates that you are a "Guest". That

means that you weren't logged in, which is why you didn't get the smilies

option. Your user name is Richard Larkin, so if you enter "Rich Larkin", it

treats you as a stranger.

I'm sure changing taste is important. Somebody

(maybe you, I don't recall) pointed out that Belouch rugs were uninteresting to

collectors until about 30 or 40 years ago, and collector interest in Turkmen

weavings, especially the bags and trappings, didn't enter the mainstream until

after World War II.

The fact that Valentiner, et al., actually objected

to collectors buying things of which they disapproved is an arrogance that some

people never seem to outgrow. One moron has spent more six years trying to

muzzle our insistence on discussing things of which he doesn't approve, and even

opened a website that he's maintained for more than four years devoted largely

to that end. I am mystified by the notion that one form of the collector

neurosis is morally or intellectually superior to all others.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 01:22 PM:

Steve

Steve:

Thanks for the heads up. I've typed up two somewhat lengthy

responses that have been lost in space. The system seems to be telling me I

don't know my password, so I'm trying another one.

Rich Larkin

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 01:33 PM:

Steve:

How frustrating. Not your fault. I won't recreate the pearls of

my earlier responses that didn't make it. I explained ad nauseam what I

had done about trying to post images by emailing them (I think) to you and

Filiberto. One point was that the first try (to you) included very large images,

then I learned (from John, I believe) that you preferred small. So I emailed (I

think) smaller versions to Filiberto. Am I getting anywhere on

this?

Sorry for the trouble, and to be cluttering up the main pages with

this. I'm not even sure I'm emailing to the right places.

Rich Larkin

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 08-14-2006 01:40 PM:

Hi Rich,

I didn't receive anything.

Click here to email

me

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 08-14-2006 01:48 PM:

Hi Rich

I don't recall receiving anything from you in the past 24

hours, but my memory for such things is pretty bad.

The image files that

we post seldom exceed 100 KB, and are seldom wider than about 550 pixels. When

they come to me (or Filiberto) bigger than that, we resize them before putting

them into the server. We prefer to receive them already appropriately sized,

because that makes less work for us. Filiberto loves to work, but I'm incredibly

lazy.

You can send e-mail to me at this

address.

I can set your password to anything you like, and you can

then change it through User CP (button on left side of screen, just below the

introductory paragraph) to something I don't know.

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 04:31 PM:

Hey Steve:

Whew! I'm almost ready to yell, "Uncle!" How pathetic on my

part. I'll try to resend from home shortly. Sorry for the

trouble.

Filiberto: I'll try emailing to you again, too. I don't mean to

make more work than necessary for you and Steve. Thank you for your

patience.

Rich Larkin

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-14-2006 05:04 PM:

Richard -

I've lost things in cyber-space too, trying to do something

long directly in the Turkotek post program. In fact it happened to me

today.

What I'd recommend is if you have a long post, compose it first in

Word and paste a copy into the Turkotek posting area. That way you always have

the original.

It's very discouraging to lose something you've worked an

hour on. I'm not even going to try to redo my lost post from earlier today.

Fortunately, the conversation has moved on a bit and western civilization is not

breathless over what I might have said.

And I have password

problems too. Just ask Steve and Filiberto.

Regards,

R. John

Howe

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 05:38 PM:

John:

Maybe not breathless, the whole of Western Civilization, but a

good chunk of it is very interested. If you settle down and reconsider, let's

hear it.

As for my password, I mixed them up, but I've regained my

composure on that. Thanks for the encouragement. And the ever fertile postings.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Tim Adam on 08-14-2006 07:36 PM:

Let's be fair

Hello all,

From Valentiner’s quotes that John posted I do not infer

that Valentier regards all of 18th and 19th century rugs as inferior to

earlier ones. He first states that the high point of rug manufacture was reached

in the 15th-17th century. Then he says that collectors do not seem to recognize

this fact, as they tend to prefer collecting rugs from later times. He does not

write that later rugs are all bad. He writes that they “usually show a

lack of clearness in design and a weak sense of color relations.

Then he

goes on to argue that there is no design innovation in rugs during the 18th and

19th centuries. Instead, later rugs merely repeat already known designs.

Valentier again uses words like “generally” or “seldom,” indicating that he does

not dismiss all later rugs.

His most exclusive statements are that 18th

and 19th century rugs “never stand comparison with those made in the earlier

periods,” and that “Every old rug, on the contrary, has a marked individual

character …” Here I would disagree. But as these statements are inconsistent

with his other statements, I would discount them somewhat and not infer that

Valentier dismisses all later rugs.

BTW, Valentiner does not use

the word decadence to describe rugs, but to describe a general attitude of

people. So, I think it is not fair to label this as a rug “swear

word.”

Regards,

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-14-2006 08:31 PM:

Hi Tim -

Well, you're a scholar and capable of close distinction, but

I think you're WAAAY too easy on these folks. For me, they are making the

argument that only they can discern truly great aesthetics and that both the

"educated public" and most collectors are to be pitied for not seeing what they

see and as a result buying less worthy material.

It's still going on

today, only the dates have changed. The arguments are identical and the

confidence of aesthetic experts is breathtaking.

My root argument is that

since it seems that there is no objective basis for any theory of aesthetics so

far (the formalists claim we're "hard-wired" but we're obviously not; we tested

it modestly once a bit, way back http://turkotek.com/salon_00011/salon.html ), there is no

reason why any of us should treat seriously the aesthetic judgments of any of

the rest of us. Too often, "it is good" is indistinguishable from "I

like."

I think the reigning aesthetics in any field are socially

constructed and therefore manipulable (and manipulated) by the dominant elites

of the time.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 09:09 PM:

Tim:

You are cutting the man plenty of slack by emphasizing his

qualifiers in those statements in which he essentially dismisses 18th and 19th

century rug production. Then, in those places where he comes in with the punch

line, unqualified, you discount the statement as inconsistent with his other

comments. Don't we have to concede that he has little or no regard for the later

rugs, for whatever that's worth?

John:

Ooh! I took a look at that

"aesthetic" link. I didn't know about that. It looks like it's going to be fun.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-14-2006 09:13 PM:

John:

Of course, I know that salon is ancient history.

Rich

Larkin

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Patrick_Weiler on 08-15-2006 04:13 AM:

John,

I see that the Holbein you showed, just under the Mamluk, has a

box-type border of serrated leaves surrounding a diamond design. Quite a while

ago (decades in computer years, but probably only a couple of years ago) I

suggested here that the ubiquituous leaf-and-wine-glass border found commonly in

Caucasian and also often in SW Persian tribal rugs was possibly derived from a

box of this type. If this box is sliced in half, then you have the leaf and wine

glass.

Just to speculate even more, it would seem likely that an old rug

with the box border may have lost several columns of knots along the selvages

and several inches of length, producing a leaf and wine glass border.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 04:27 AM:

Hi Pat -

I think the thrust of your observation about the "wine glass

and leaf" border is correct.

In fact, Wendel Swan made a presentation at

an ICOC conference a few years ago in which he held that many devices that we

see or interpret as representational are in fact instances of a largely

geometric Islamic design tradition. This particular border was one of his

examples.

I don't think we have to resort to "knots wearing off" to

suggest a source for the "wine glass and leaf" border. Even more likely, it

seems to me, is that a weaver somewhere decided to use only half of this broader

one.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 05:44 AM:

One Example of Design Change Over Time

Dear folks –

In 2002 Walter Denny, the UMass-Amherst rug scholar,

curated an exhibition at The Textile Museum here in Washington, D.C. entitled

“The Classical Tradition in Anatolian Carpets.” Denny also wrote and the TM

published an associated full-color catalog with the same title.

Denny’s

chief strategy in this exhibition was to take some key types of Anatolian

carpets and to provide various interpretations of these designs over time. He

used the “Holbein” varieties, the “star” and “bird” Ushaks and several others in

this way.

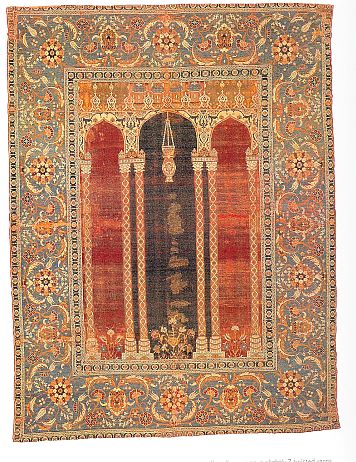

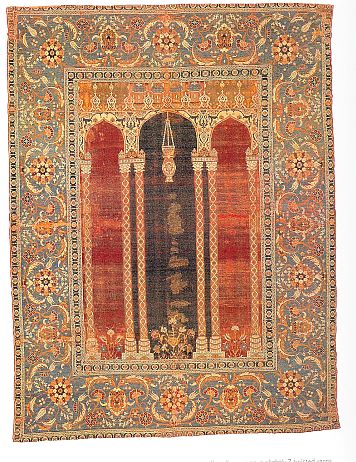

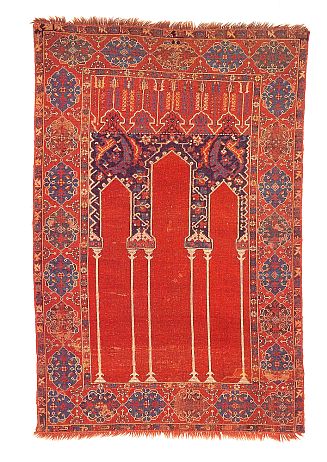

One of the classical designs that Denny selected was the niche

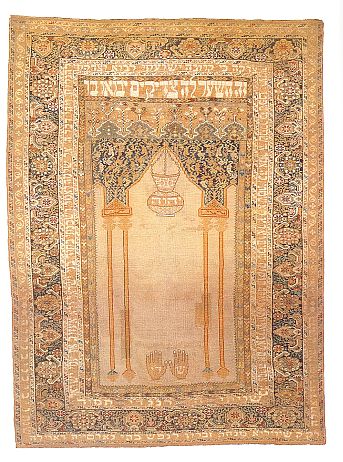

format carpets with “coupled columns.” He began with the one below:

This rug is among

the most famous of its type. It came from the Ballard collection, has a silk

foundation and the twist of its wool suggests that it was woven either in

Istanbul or Bursa rather than in Cairo. It is dated to the second half of the

16th century.

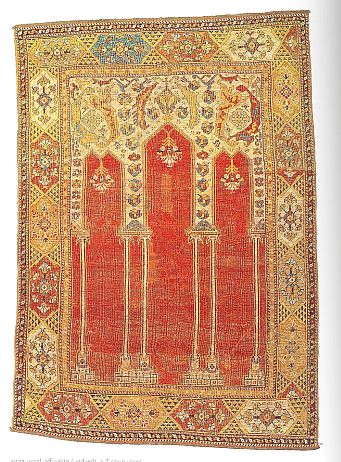

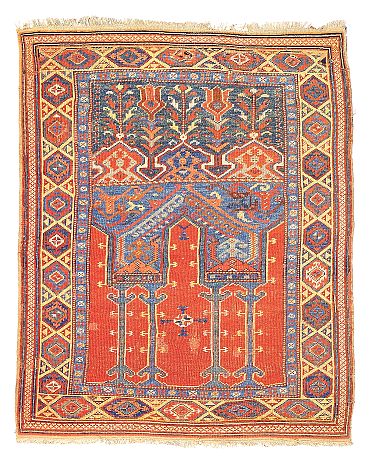

Another example is the piece below thought to have been

woven in western Anatolian in the mid-17th century.

Denny asks that we note the

changes that the area above the niches have undergone (they have become a kind

of “fish” design) and the fact that the curvilinear nature of the border in the

fist piece has been entirely lost.

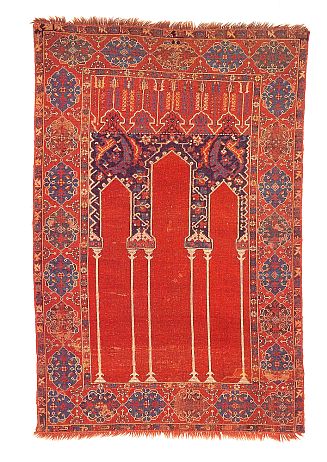

A third example is from the TM’s own

collection and is said to have been woven in central Anatolian in 18th

century.

Denny points to the fact that the “flowers of the parapet have

been doubled, the spandrels exhibit a regularized border design in their lower

parts and the columns are very simple stripes with identical capitals and bases.

But he also says that the use of color in this third example give it a “presence

and liveliness lacking in many early examples” of the same design.

Denny’s next example, below is coupled-column torah curtain woven

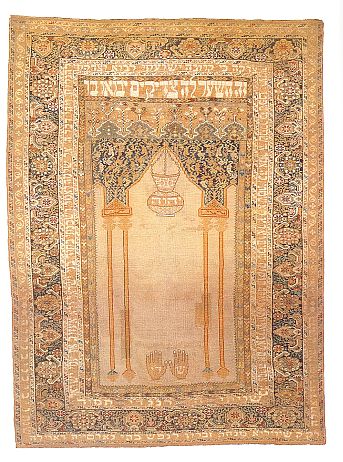

Ghiordies, western Anatolia in the 19th century. (Denny has a thesis that this

coupled-column design likely originated in Spain in the 15th century because the

architectural shape of the arches in the first example occurred only in Spain at

that time. He feels it likely that Spain’s Jewish weavers, driven out of Spain

by the Inquistion, but welcomed by the Ottomans, brought this design with them

often in their torah curtains.)

Denny said that this is the

most lavishly inscribed torah curtain of this type that has survived. He notes

that the fine Ghiordes weave has permitted the design here to echo and retrieve

some aspects of the first rug (the border, for example, is closer again to the

curvilinear) but that “the bases of the columns now float weightlessly in the

field.”

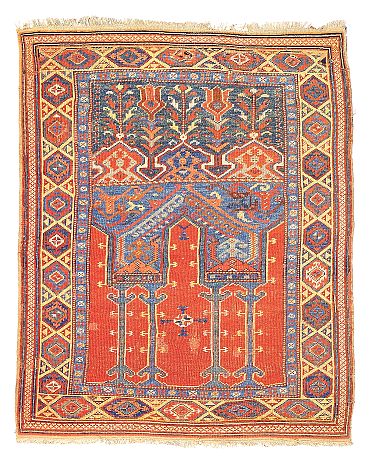

Denny’s next example, below, is an Ushak rug from the 19th

century.

He describes it as a coarsely woven, simpler, more

color-dominated version of the original in which the area above the niche has

become more prominent and the columns have become “an almost insignificant part

of the design.”

Denny next presents a fragment from a coupled column

saff.

Likely woven in Ushak in the 18th century, it exhibits large

scale arabesques in its spandrels, niches with cusps and alternating red and

blue fields. The plain columns have capitals but no bases.

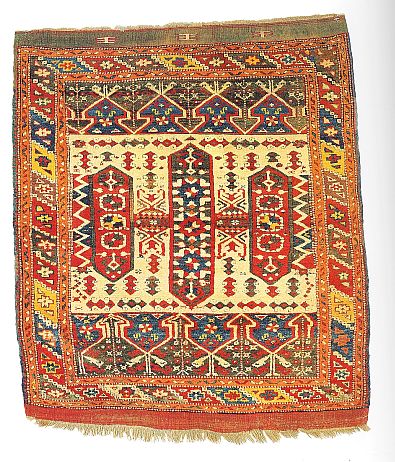

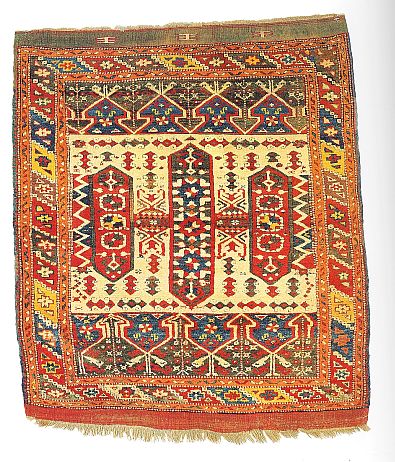

Denny

describes the piece below (19th century, northwestern Anatolia) as the “ultimate

evolution of triple-arched and coupled-column ‘sajjadah.’” The parapets have

been reflected vertically and the columns have disappeared entirely.

Denny says “The

artistic result is as beautiful a village rug as one could imagine; a work of

art that combines striking originality of design and color with a design

tradition which can be traced back almost four centuries.”

A final piece,

below, is described by Denny as completing the “circle,” since now the reflected

parapets have been moved into the field of a niched design.

Denny describes this 19th

century fragment as “free and spontaneous, if not exactly precise and

well-planned…” Again color draws one to this piece.

So there are some

versions over time of a basic classical design. What do you think? Does

aesthetic excellence reside only in the first two examples in this sequence? Has

the influence of Ghiordes been visibly pernicious? Does color use weigh with

design complexity and articulation? Do the last four examples simply not weigh

with the first one? I leave it to you.

I will say that this was a fairly

large exhibition with several other design types included. Denny volunteered

during his walk-through that if he could take only one piece home from this

exhibition it would be this one.

Valentiner and his expert

peers would cry.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 08-15-2006 06:14 AM:

Hi John,

The examples you posted show not only the evolution (or let’s

call it development) of a classical design over time, but also its transfer from

an urban workshop to an increasingly rustic milieu.

I bet that Valentiner

would have considered the 19th specimens above as decadent and degenerated. I

find them charming.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 08-15-2006 06:54 AM:

Hi John

I think the notion that designs of the two village rugs are

evolutionary descendents of the older ones is an interesting speculation, but

that it isn't supported by very compelling evidence. An awful lot of what appear

to me to be ad hoc assumptions are involved in the

argument.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 08:40 AM:

Hi Steve -

I have stepped out of one argument into another momentarily

to show how Denny presented different versions of what he sees as a particular

type Turkish classical design.

Although, he does make at least one

seeming evolutionary reference in his description of the next to the last

example, for the most part his discussion is taxanomic.

I am with you

that we are not usually in position to say really whether a given design is

based on another. What we can, I think, say is that particular designs resemble

one another and then point out the differences as well.

Gayle Garrett, a

local rug specialist who presents sometimes at the TM, entirely objects to any

evolutionary or developmental language when talkng about rug designs, saying

that we should talk only about differences. She also rejects any evaluative

language in talking about these. I don't go quite that far.

Her argument

sometimes looks like that of an interested party because she is active in the

DOBAG project, but it is likely still basically sound.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 08-15-2006 09:05 AM:

Hi John

I think what led me to believe Walter was saying that this is

an evolutionary sequence was this,

Denny describes the piece below (19th

century, northwestern Anatolia) as the “ultimate evolution of triple-arched and

coupled-column ‘sajjadah.’”

This was reinforced in my hopelessly

linear mind by

... described by Denny as completing the “circle,”

...

I share Gayle Garrett's misgivings about talking in terms of

design evolution, at least about doing so without explicitly recognizing the

speculative nature of the topic. This is not to deny that it provokes thought

and is kind of fun. I am bothered by Denny's analysis mostly because it involves

so much moving things around, adding elements and deleting elements to get from

one point to another. If you do enough of that, you can get from any design or

motif to any other design or motif, whether they are historically related or

not.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-15-2006 11:04 AM:

Garrett

John:

You wrote that Gayle Garrett "...objects to any evolutionary or

developmental language when talking about rug designs, saying that we should

only talk about differences." I'm not sure I appreciate what that means. Could

you elaborate? Also, she rejects evaluative language. I don't get that

either.

How is her approach essentially different from Walter

Denny's?

Thanks.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 11:25 AM:

Richard -

It's always a bit dangerous to make someone else's argument

for them, but since I share some of her position, here goes.

A great deal

of the literature on oriental rugs is taken up with describing either how the

designs in older rugs change as they come forward in time or with arguments for

the likely sources of particular more modern designs. You can find the former in

almost any old rug book you pick up. Christine Close, provides an example of the

latter in her analysis a few years ago of the likely sources of the central

devices in the "eagle" Kazak. Much of this analysis is presented in the language

of "evolution," of "development," and there are often comments alleging "design

degeneration."

The problem with making evolutionary arguments is that we

do not know the weaver's intent. We can cite similarities and point out seeming

conventionalizations, but the real connections between two similar designs are

not made in this way, excepting through inference.

So some have suggested

that we drop the claim that we know much about evolutionary paths of rug design

and restrict ourselves to what we can in fact do: taxonomy.

So that is

the first part of what I see as Ms. Garrett's argument. Give up any suggestion

that we know much about the "development" of designs because it is likely that

we do not.

But she seems to go further. The old rug books often

denigrated newer versions pointing out what has been lost in

conventionalization. Ms. Garrett will admit to "differences" but not to language

that suggests, for example, that more simplified versions of seemingly similar

designs are lower on some aesthetic dimension than the older, more elaborated

ones. She objects to any suggestion of either aesthetic "development" or

"degeneration" in description of differences between rug designs. She will only

acknowledge "differences."

I hope that is clearer...and

accurate.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-15-2006 11:55 AM:

Thanks, John. Very helpful, and very interesting.

I know Walter Denny

has been making the arguments for design development in Anatolian carpets much

along these lines for quite a few years now. Certainly, there is some connection

between, for example, the first two examples in your post. But as you say, we

only know that through inference.

Are you impressed with the observation

that the weaving medium, operating as it does on vertical and horizontal lines,

enforces a straight line geometry that weavers (collectively over time) tire of

fighting? In other words, curvelinear designs are achieved by a special

discipline, and angularity is ultimately self-fulfilling.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 01:57 PM:

Richard -

I can't say I've heard that particular thesis, but as you

say it it seems plausible. I'm sure you have heard that some more restrictive

techniques tend to produce particular sorts of designs.

I do know one

collector who is impressed with the notion of being able to "circle" the basic

rectilinear character of weaving. He is an actuary and so a pretty good math

student and has said repeatedly that one thing that drew him to oriental rugs

and that continues to attract him is the small "miracle" of producing

curvilinear designs on a rectilinear grid.

It is not an accident that he

collects only silk rugs, since their high knot count makes it possible to draw

quite "smooth" curves, even circles, on such a matrix.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 08-15-2006 02:09 PM:

Hi John

Circles and smooth curves are almost always the result of

weaving from a cartoon. That's why you hardly ever see them on rustic or tribal

weavings. Your friend's silk rugs, like most silk rugs, are probably urban

workshop products made from cartoons that show the placement of every knot.

Don't tell him this - let him enjoy the illusion that the weavers were

performing miracles that he now holds in his hands.

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 05:13 PM:

Steve -

Oh, he's quite aware. He's not naive about what he is

admiring. He's an astute enough mathematician to see clearly how the "miracle"

is achieved.

And he is under no illusion that he is buying pieces woven

from memory. The "perfection" of the silk rugs is another thing he admires, so

cartoon-based designs do not diminish his enjoyment.

And he is not put

off by a rug being new either. There are some very nice silk rugs being woven

these days. The Chinese are sometimes doing so well that some Turkish weavers

are buying Chinese rugs, weaving a "Hereke" designition into them and trying to

sell them as Herekes.

Some experienced collectors don't approve of his

collecting, but he's steadfast in what he is about.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Doug Klingensmith on 08-15-2006 06:07 PM:

Thanks John for posting that great sequence of rugs. Walter Denny also wrote

the little Smithsonian sponsored book on oriental rugs- they must have printed

lots of them as they are available for $5.00 at the usual on line book sellers-

I include a copy along with every weaving I give to somebody.

regards,

d.k.

Posted by Steve Price on 08-15-2006 07:04 PM:

Hi John

Oh, I wasn't expressing disapproval. In fact, I own a silk

Hereke prayer rug, circa 1960, that I like very much. I just had the impression

that he thought the weavers who could make circles must have been technical

masters.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 08-15-2006 07:44 PM:

Hi Doug -

Yes, Denny's little Smithsonian "chestnut" you mention is an

ideal "give-away" book for someone new.

Another is Preben Liebetrau's

"Oriental Rugs in Color," which not only has a handy size and lays out the

typology that Jon Thompson popularized in his own basic book, it has remarkable

color for a book first published in the U.S. in 1963.

And for some reason

you often find the dust jackets still intact on the Liebetrau

volume.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 08-15-2006 08:30 PM:

Dear John,

I wasn't aware of Gayle Garrett's argument, but I like

it.

I've gotten to much the same place in a slightly different manner.

Evolution (or devolution as is sometimes claimed) requires knowledge of what

came before. So if an atelier produced rugs over a period of time and made V1.0,

V1.1, V1.2, V2.0, etc. of a similar design, evolutionary tendencies could be

confirmed. But that's not the way it worked. We're sitting here hundreds of

years and thousands of miles away comparing one rug from one place with another

probably made somewhere and somewhen else - and then stringing them together in

a design evolution.

In science this is called "dry

labbing".

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-15-2006 09:57 PM:

Hi John:

That Liebetrau book was the first one I got when I initially

contracted the disease. I had the impression back then it probably covered about

60% of known production. Turned out I was mistaken.

P. S.: The dust

jacket's still on it. Must be a good grade of paper.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Tim Adam on 08-15-2006 11:18 PM:

Hi John,

Thanks for posting the coupled columns niche format rug

sequence. Very interesting, indeed. Among the first five rugs the choice is

obvious (based on just the digital images). The first piece is truly

outstanding, and I am surprised by Denny's decision to go for the third one. But

he presumably saw all pieces in the wool, and we have only the digital

images.

The comparisons with the last two village rugs are more

difficult. The difficulty is to disentangle quality from personal taste. I might

go for the last one, because of my personal preference, but I'd still consider

the first rug as the most accomplished one.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-16-2006 09:09 AM:

Hi Steve,

On the matter of weaving curved lines from cartoons. Some

rugs we consider tribal, such as certain Qashgais, show some fairly

sophisticated (and well drawn) designs. There are some in a pretty elegant

version of the herati pattern, even some of the boteh we were recently looking

at on one of these threads. Would you think they are drawn from cartoons? Or are

you referring only to the more elaborate designs modeled after Persian and

classical carpets, etc.?

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Steve Price on 08-16-2006 09:19 AM:

Hi Rich

I wasn't thinking of Qashqa'i when I wrote, and would call

them exceptions to the rule. I left a little wiggle room for exceptions in my

text. Note the hedging in the boldface type (added for emphasis

here):

Circles and smooth curves are almost always the result of

weaving from a cartoon. That's why you hardly ever see them on rustic or

tribal weavings.

My momma didn't raise no dumb boys.

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by R._John_Howe on 08-16-2006 11:19 AM:

Richard, Steve -

It's remarkable how well some weavers can draw

credible circles on pretty coarse weavings. I've seen some Ersari examples that

can't have been much beyond 60 KPSI. And some of those might well have been

woven from memory.

And one of the real technical achievements of the

Indians who "wove" the Chilkat dancing blankets is that they learned how to

combine species of braiding with weft twining to make circles on flatwoven

fabrics done on a warp-weighted loom.

So there's a lot a weaver ingenuity

that's been applied over the years to circle drawing.

(By the way, I put

the term "wove" in quotes above because folks like Marla Mallett do not see weft

twining as a species of "weaving." It does not meet their standard for

"interlacing" of the warps and wefts, since no shed is involved. Just an

aside.)

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 08-16-2006 11:38 AM:

Weavers of Chinese rugs were masters of making curved lines and circles with

<30 kpsi. Look at some pictures of "wheels", lotus blossums, or clouds in old

Chinese rugs.

Posted by Wendel Swan on 08-16-2006 12:22 PM:

Hello all,

Whether one calls it evolution, devolution, degeneration,

transition, development or Garrett’s meaningless “differences,” various

processes of copying are at the heart of weaving and design proliferation. Any

pattern that is repeatedly copied is going to vary, change, devolve or evolve

(you pick the verb).

Walter Denny’s sequence illustrates that one

long-term result of copying is that certain elements are extracted and become

independent of their earlier contexts.

The following rug could be

inserted after the saph to show another possible step in Walter’s progression.

In this case, you must view the ivory as the columns, not merely as the ground

for what some will want to see as green cypress trees. A few inches are missing

across the center.

All of the rugs Walter shows are just a few of the dozens or

hundreds of similar rugs. And there must have woven dozens or hundreds more in

various transitions. I don’t believe that it is speculation to observe such a

continuum.

John, you wrote: “The problem with making evolutionary

arguments is that we do not know the weaver's intent.” I think we do. The

weaver(s) intended to copy all or part of some other rug or textile or a

cartoon. Period. Variations may occur either intentionally or unintentionally.

It doesn’t really matter which. In any event, we end up with a lot of variants

that look similar and then another batch of further variants that look similar

to one another.

In my view, here on Turkotek undue emphasis is often

placed upon the work, status or “intention” of an individual weaver. We don’t

recognize a Salor or Qashqai or Kurdish rug because of what one weaver may have

done or what her intentions were. We can recognize and categorize them because

of the enormous quantity of similar weavings produced by a community or

culture.

In the past few years I’ve come to believe that most collectors

and even authors view rugs myopically. I cannot pretend to have the answers, but

all would benefit by trying to look at rugs in a much broader historical,

artistic and cultural context.

Walter’s quite conservative approach with

this limited number of pieces is precisely the kind of analysis from which all

can learn. I’m surprised at how quickly it was abandoned as speculation and as

not demonstrating any more than “rugs are different.”

Wendel

Posted by R._John_Howe on 08-16-2006 12:47 PM:

Dear folks -

This has the makings of an interesting and potentially

useful discussion.

Jerry Silverman says that Gayle Garrett's argument

make sense to him and Wendel Swan, an old Chicago area neighbor, in years past,

says that Garrett's argument is "meaningless."

Can we hear more from both

sides?

Without diffusing any of what might be said, Wendel let me ask why

you feel that the noting of taxonomic similarities and differences would be

"meaningless?" A great deal of biology is taxonomy.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 08-16-2006 01:01 PM:

Hi Wendel

I think I was the primary objector to Denny's presenting the

thing as an evolutionary sequence. I have little difficulty with the first

several examples, in which the changes from one form to the next are fairly

simple and straightforward.

The going gets rough, I think when he gets

to the village pieces. To get the first of these into the sequence, he

says,

The parapets have been reflected vertically and the columns have

disappeared entirely.

That's a lot of changes.

To get the next

one in,

... the reflected parapets have been moved into the field of a

niched design.

The reason I object is that any form can be morphed

into any other form if you make enough appropriate modifications to it. With

patience, the image of any rug can be converted into a picture of an elephant

eating a head of cabbage in a (long) series of single steps. So, I get wary when

someone argues that it is an evolutionary sequence if several steps, especially

if some are really multiple operations presented as single steps, are needed to

accomplish it. Not that it's impossible for the sequence to be correct, only

that it's impossible to create compelling evidence that it

is.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-16-2006 09:38 PM:

Folks:

It may be that I do not understand the respective arguments

adequately, but the two positions do not seem mutually exclusive. Rather, the

two sides appear to be carrying on the tradition of the Miller Lite campaign:

One side is shouting "Tastes great," the other answering, "Less filling!" Both

can be true.

I refer to the first sentence of Wendel Swan's comment above

and suggest it is a truism. With that thought in mind, I offer the following

additional comments that I think are self evident and do not require objective

proof:

-Some copying must attempt exactness. This endeavor puts the

weaver in the position, in effect, of using other weavings as the cartoons Steve

was alluding to above.

-In some cases, the copying must constitute less

of an effort in precision; and the nature of the weaving medium being what it

is, viz., a collection of horizontal and vertical elements, the weavers (and

their designs), over time, surrender to angularity and give up

detail.

-In some cases, weavers must size up what they are doing and make

conscious decisions about their copying, frequently by way of simplification.

(It has often occurred to me while reading commentators' assessments of what the

weavers must have been thinking, that whatever they were thinking, they probably

understood weaving much better than most of us ever will.)

I don't doubt

that all of the above dynamics have been in play throughout the history of the

weaving of pile rugs. The results are all around us. As an example of the third

suggestion I made above, I offer two images of a design probably familiar to

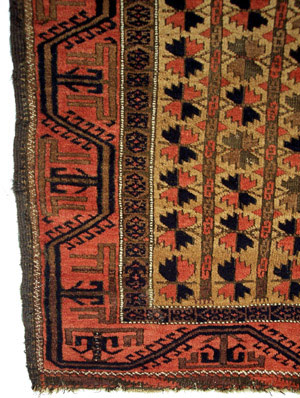

most of us.

I refer to the border design, which is familiarly called the

"boat border." One example, articulated with an abundance of detail, is from a

Yomud rug. The other is a Baluch. I will not attempt to prove who is the

ultimate copyist, but most will assume that the Baluchi weavers are famous (or

notorious, depending on the commentator) copyists of the Turkoman. It is not

possible to say just what the connection is between these two examples. However,

I suggest that somewhere in the interplay between the peoples in these weaving

regions, the border manifest in the Yomud example was known to the Baluch

weavers in pretty much its full form. The Yomud is probably somewhere in the

nineteenth century, give or take. I would estimate the Baluch to have been

produced sometime early in the twentieth century. I don't think these statements

are controversial.

My point about these two rugs is that I think it is

quite likely that the simplifications of the boat border design were implemented

consciously by the weaver. Certain elements were preserved or suggestions of

them were adopted. The result is “clean.” It seems hardly probable that the more

complex elements, present in the Yomud version, fell out of the Baluch version

over time, the way (I'm told) we lost our tails. (I apologize in advance for any

offense taken over that remark.) If I am approximately correct in this, I

suggest that the dynamic has repeated itself countless times. When we look back

over the motley collection of products that have survived, we call it evolution.

It's a reasonable term as long as you don't expect too much from it.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 08-17-2006 03:01 AM:

Evolution, simplification, degeneration - all these terms are being used to

imply a chronological progression from the old to the newer, from the more

complex to the simpler, from the higher "energy level" to the lower.

Call it design "entropy", if you will. It is a lens through which we see

and interpret what we see.

But while entropy is a physical law, there is

no reason why it has to be a design law. I have to look no further than my floor

to see an Afghan rug made in 1980 that has borrowed many motifs and made them

more elaborate.

I'm not saying design entropy doesn't take place. I'm just

suggesting that it needn't necessarily take

place.

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by Richard Larkin on 08-17-2006 07:59 AM:

Folks:

I would like to add a comment referring to the rugs presented

by Walter Denny, courtesy of John. I agree with Steve Price that the leap to the

village rugs, and perhaps the one posted by Wendel Swan, is harder to accept if

the proposition is anything like a direct link. The movement from example one to

example two, on the other hand, is virtually incontrovertible I would

think.

I do not necessarily reject the link in the later pieces, and am

loath to second guess someone like Denny, a professional scholar and art

historian, on something like this. It's just that the link isn't so obvious to

me within the scope of the examples shown.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Wendel Swan on 08-17-2006 04:00 PM:

Hello all,

First, I want to emphasize that I only said that one

long-term result of copying is that certain elements are

extracted.

Second, I did not assert any direct link between the small rug

and any others. It is virtually impossible to link any one rug with any other

rug(s) and thereby prove an “evolutionary” process. My point was that we must

view as much of an entire corpus of weaving as is possible. When we do, we can

sometimes see similar examples of many links, not the

link.

Similarly, Walter Denny was probably not trying to establish his

examples as direct links in an evolutionary process. Having spent some time

looking at architectural connections to weaving, I wanted to provide one example

among many of one phase of the process.

In the case of the first two

Denny examples, I doubt that we are viewing evolution as such. Both are

undoubtedly the product of highly supervised weaving, the designs having been

perfectly developed and articulated off the loom before weaving began. Both

reflect a timeless interest in architectural elements as motifs, as do countless

others. If they represent any type of “evolution” at all, they are variations by

virtue of having been woven in different places and at different

times.

One can readily see the same type of variation in the 2-1-2 design

of early Turkish rugs, the small pattern Holbeins, and the later Karachov and

Kagizman versions.

Memling guls come to mind as another ubiquitous

pattern that is probably more than 1,000 years old. They have been interpreted

by virtually every weaving society.

John, you wrote: “Garrett … entirely

objects to any evolutionary or developmental language when talking about rug

designs, saying that we should talk only about differences.” (Emphasis

supplied.) If she is saying that we can’t assign aesthetic values to changes, I

can at least understand the argument. But if she contends that we must confine

ourselves to merely saying that rugs are different and that there is no

evolutionary process (a neutral term), I’ll repeat that I think merely reciting

differences is meaningless.

In what I think is an effort to dispute the

extraction and simplification theory, Jerry has shown “an Afghan rug made in

1980 that has borrowed many motifs and made them more elaborate.” Clearly,

several motifs were borrowed, but they look more jumbled than elaborated. Sorry.

While cross-cultural borrowing is ancient and even interesting, this is an

unfortunate example of what happens when a group manufactures a rug with no

connection to an earlier example and its culture.

Wendel

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 08-17-2006 04:04 PM:

Dear Wendel,

"elaborated" - "jumbled"

"tomayto" - "tomahto"

Cordially,

-Jerry-