Posted by R. John Howe on 10-08-2005 09:06 AM:

Central Asian Attribution Puzzle

Dear folks -

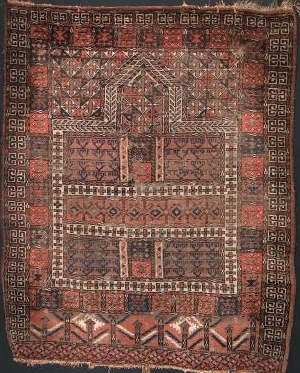

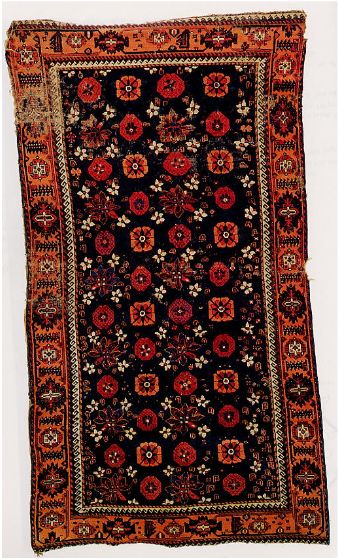

I recently bought a Central Asian piece that is of the

sort I collect frequently: bad condition, but interesting in character.

I do not yet have it in hand, but expect to in the next week or so.

Meanwhile we can speculate a bit about it, perhaps even offer an informed

opinion or two. Here are some images.

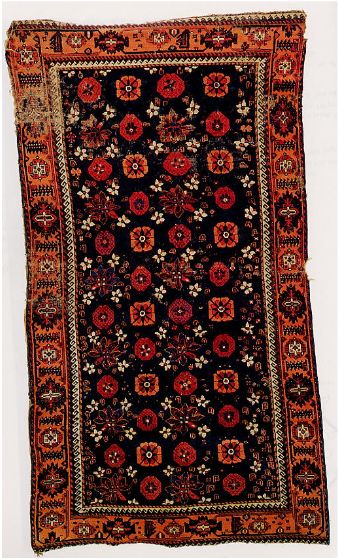

First one that shows it

overall.

It's about 3.5 ft by 5 ft if I recall correctly.

Here

are a couple of images of the mina khani field.

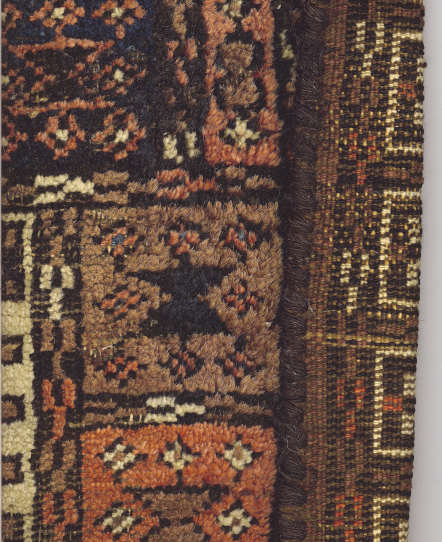

And this is a shot that

lets us see pretty well what its borders are like.

Finally, here is a

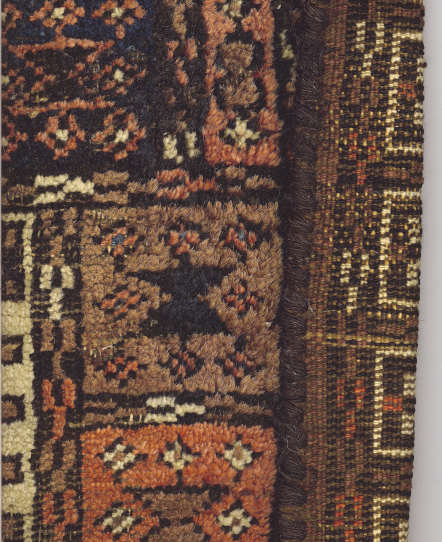

fairly close image of its back.

Now the temptation may

be to look at just a couple of the indicators here and to move to ready

conclusion. But a correct attribution of this piece may require a little more

patience and tentativeness than that which might be tempting initially.

I

will gradually reveal what I have been told about this piece, but want to begin

by asking for your own attribution suggestions and the reasoning (please) on

which they are based.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-08-2005 10:42 AM:

Hi John,

Okay. It looks like a nice and worn Ersari Beshir, but from

what you write you obviously don't think that it is an Ersari.

Jourdan wrote that

this kind of design was used also in the Amu-Darya region. Do you presume your

rug was woven by Uzbeks, perhaps?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 10-08-2005 11:20 AM:

Hi John

Looks pretty Ersari to me, too.

But wait! You imply

that the obvious is misleading. So it must not actually be Ersari.

But

you probably said what you said just to throw us off track. Yes, that's it. Now

I'm onto your little game.

Ersari it is. Beshir

type.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 10-08-2005 11:42 AM:

Out on a limb

Hi John,

The picture of the back is sort of fuzzy, but it sure looks

like Baluchi work to me. It'll be interesting to read the full

story.

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by James Blanchard on 10-08-2005 12:37 PM:

Out on a limb...2

Alert: Novice opinion coming up....

The back does look "Baluch" to me

too.

That "S" border also strikes a "Baluchi chord" to me

also.

Ditto for the white warps.

James.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-08-2005 01:07 PM:

Compare and Contrast...

Hi John

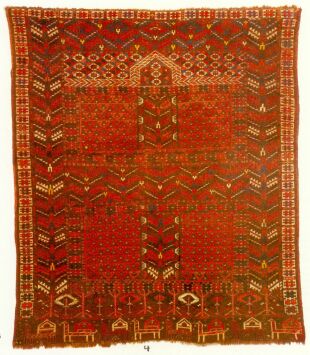

Find below an image of a classic Beshire chuval in the Mina

Khani pattern,ancestral to Herat if I'm not mistaken, and a detail from the

corner of a Beshir from one of Joe Fell's "Rug Mornings"

Notice the

similarities, the kindered field, the "S" border and floral forms of the elem,

as mirrored by the end treatments of the rug.

In the rug we have the

"dice" border and "judor"or almond borders(which is also seen in various

incarnations in products of other tribes) which say Turkmen. The camel ground

for the judor border seems unusual, and might indicate that there has been loss

to the sides. Is this weft material we see to the left of the third detail

image? Could this be cotton?

With it's profusion of small flower petals,

the field more resembles the drawing of the lattice field of Baluchi

renditions,

and the following from a discussion here on Turkotek entitled

The

Internal Elem Configuration and its Markings.

And our subject

rug again.

Next is from the Lattice

thread here on Turkotek.

While on the lattice subject, let's not forget

the following images from 1420 and 1429 miniatures in von Bode's "Antique Rugs

From The Near East" (pg.85) which is accompanied by the following

statements

"then regular repetition of certain definite ornamental forms

by the most diverse book illuminators permits us satisfactory conclusions

regarding their actual decorative stock-in-trade. According to these

reproductions the field appears to have been filled with either with a simple

scale-pattern or latticework, or else with a continuous and usually rather loose

plaited design, in which stars, rosettes, hexagons or other incidental motives

were interspersed".

Dave

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 10-08-2005 04:51 PM:

If those are cotton warps, its not Ersari; probably some Persian knock-off,

but with outstanding colors (presuming that my monitor is accurate). Actually

the back looks almost Senneh like.

So, John, what was your initial

opinion, before some one told you something that you plan on revealing?

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-08-2005 09:44 PM:

Dear folks -

This piece arrived today and so I can supplement (and

correct) some information I've given on it.

It is about 44 inches

(approximately 111 cm) wide and 75 inches (about 189 cm) long.

The knot

is asymmetric open left. There is pretty marked depression of alternative warps

(there is definite "ridging"). The piece is quite finely knotted. Each knot node

(looking at the back) is roughly square, so a given knot is about twice as wide

as it is tall). So there are going to be about twice as many knots per running

inch vertically as there are horizontally. I just counted in one area. There are

8 knots in a horizontal inch and 15 in a vertical one. So it's about 120 knots

per square inch (1860 knots per square decimeter).

The warps are not

chaulky white with this piece in my hands. They are at least what would be

called a medium to dark ivory. They have some of the brushy quality of goat hair

warps (I've been feeling them side by side with those on a Tekke torba I have

that definitely has fine white goat hair warps). The warps on this piece feel

softer than the goat hair, but are also softer than some wool warps on other

pieces here. I am not sure (Eiland would demand a microscope) but I wonder if

these warps are not camel hair (I also have a piece of camel hair to feel and

compare).

The marked whitish fuzzy looking quality of the back in the

image above is not general (it may come from some damage in some areas that was

not apparent to me as I was considering this piece) and I will provide some

direct scans of other areas of the back in the morning.

With this piece

in hand, the wefts seem brown in areas of darker pile, but gray in areas of

white pile. We'll have some close ups of bare areas tomorrow so you can help me

decide that. I'll also ask whether you see any sign of cotton in the

wefts.

The white cotton selvedges, most of you will know, have nothing to

do with what this rug is and were added at some time for reasons

unknown.

The colors of the piece are pretty close, in my view, to what I

saw on my monitor. I have not seen it in full sun, but so far see two reds, two

blues (both darker), a dark brown, white, yellow-tan and a darker blue-green.

That's eight colors if I am right.

The handle, feeling the surface of the

back, is firm, even a little hard. Still the piece is thin and

flexible.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-09-2005 06:20 AM:

Hi John

The characteristics you just described probably eliminate

Ersari as an attribution. My best guess now would be Belouch, who use lots of

Turkmenoid designs and colors.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-09-2005 07:07 AM:

Dear folks -

We can't really say "by dawn's early light," since it's

dark here yet, but here are a few more images of, and thoughts about this,

piece.

First, here is an effort to give you a somewhat closer look at the

designs on the ends of this rug.

Secondly, notice that

the yellow ground minor border which entirely bounds the mina khani field is

also placed as a horizontal band above these endings.

Could this piece be an

engsi (Reuben offers one with a mina khani field in one of his catalogs)? And if

not why not?

The two images below are direct scans to try to give you a

basis for helping me decide what I think is the case: that there is no cotton in

the structure of this piece.

The first darkish image is from the back and

it's likely hard to see wefts adequately.

The white flecks

visible in some places are I think the ivory warps peaking through.

This

second direct scan of a bare area from the front and wefts may be seen better in

it.

I don't see flecks of white in them.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-09-2005 07:43 AM:

Hi John

You ask, "Could this be an ensi?" I guess it could be, but I

see no compelling reason to conclude that it is one. The knotting - asymmetric

left - nearly eliminates most Turkmen origins except Salor or "Eagle group

Yomud", and it is pretty clearly neither of those.

Are you sure there

aren't some missing borders along the sides? The white selvage is unlikely to be

original, and the horizontal minor border that separates the skirt from the

other borders looks incomplete.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-09-2005 08:31 AM:

Hi Steve -

The asymmetic open left knot does not in and of itself

eliminate the possibility that this piece could have been woven by Ersaris.

There are Ersari pieces with both level and depressed warps that have asymmetric

open left knots. Loges in his chart at the end shows four, two each with the

different warp treatments.

Now about the engis question: you're seeing

what I'm seeing but describing it better. The initial things that might raise an

engsi suspicion is the general size (Ersari engsis can be quite large) and the

elem-like endings, although some purists argue that an engsi can have only one

elem and this piece has this elem-like treatment at both ends. (Rueben's engsi

with a mina khani field has only one elem and that at its bottom.)

But

the piece also seems pretty narrow in relation to length for an engis. Here your

suggestion that it might well have been wider since the yellow ground border

systems above the row of elem design might indicate that this border system also

extended up both sides. If so, (and I think that likely) then this piece was

originally quite a bit wider and on the length to width dimension (only) the

possibility of its being an engsi is increased. But this same possibility also

reduces the chances of its being one since the separated "elem-like" treatment

of the ends disappears if this border extended also around the sides. The piece

becomes simply a rug.

So where are we?

What pieces show an

asymmetric open left knot?

Salor (no one would suspect that this piece is

Salor)

Ersari

Some of the "eagle group" pieces

Arabatchi

I

think we can eliminate "eagle group" on the basis of knot count. Eagle groups I

and III are those with an asymmetric knot open left. O'Bannon in his summary of

eagle group characteristics says that group I pieces vary from 2537-4240 per sq.

dm. and that group III varies from 2475-2898 per sq. dm. both of these ranges

are well above the rather modest 1860 per sq. dm. we calculated for this

piece.

The yellow ground meander border is often thought to be nearly

signature Ersari.

But the knot count also makes Ersari questionable in

the other direction. Ersari pieces do vary a lot in their knot count (in part

because we have not been able, adequately, to define this group so far) but in

his convenient table Loges reports Ersari knot counts mostly in the 700-1200 per

sq. dm. range. Only occasionally do Ersari pieces in his table rise to the

1500-1700 per sq. dm level and only one piece, that Loges includes, reaches 1800

dm. My sense is that this piece is likely too fine to be an Ersari.

So we

seem to be pressing our selves toward Arabatchi, but there are problems here

too. Arabatchis are reputed usually to have silk and/or cotton in their wefts

and we seem not to have any here.

So what do we come to? Balouch, I

suppose, might be defended, but I'd want to hear a better argument for it than

what I've heard so far. Or are we forced to retreat to "Middle Amu Dyra" (that

new term of uncertainty) or even to "Central Asian" indicating that we really

don't know?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Walter Davison on 10-09-2005 11:52 AM:

Hi Mr. Howe,

In your analysis, you are relying heavily on the

structural aspects of this rug. But what about all those pictures above of the

Beshire design that this rug exhibits? Why is it that you are ignoring - maybe

the word ignoring is not correct - or at least not taking into account more the

design features of this rug? It does not appear to me that you have addressed

this point. Aside from that, are not the Ersari made up of as yet not completely

well-defined subgroups that perhaps made more densely knotted rugs that would

compare to this piece? And if that is so, why would an Ersari attribution be

ruled out on that basis?

Walt

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-09-2005 01:17 PM:

Hi Mr. Davison -

Steve Price chides me from time to time about my

tendency to treat structural factors more importantly than similarities in

design.

I do do that (its far more costly for a weaver to change

structural things than it is for her to weave a new design, so structural

characteristics tend to be more stable and to change more gradually) but I also

acknowledge that design indicators can be important sometimes.

One of

the problems with some of the general tribal designations that we currently use

(like Yomut and Ersari especially) is that they are likely far too broad and

we're not at all sure of what they are composed. People have, for example, begun

more frequently, and a little self-consciously, to say "Yomut groups" rather

than "Yomut."

And although it seems likely that "Beshiri" is a more

urbanized kind of "Ersari" (there is a town with the name Beshir) the

distinction has not yet been sorted out. Robert Pinner and Elena Tzareva were

actively working for a time on a book on "Beshiri" weaving, but Robert died, and

I am unclear how that work stands.

More recently some experienced

collectors and students have begun to say such things as "not Ersari" without

saying much further about what it might be instead. "Lakai" too has been

criticized as being far too widely applied. And recently on Turkotek, Andy Hale

suggested that some saddle covers that some of us have blithely been calling

"Beshiri" are probably instead some sort of Afghan production. And I referred in

my posts so far to another recent tendency to say that something is probably

"Middle Amu Dyra" without going further.

This is because nearly all the

Turkmen tribes went through there at some time or other, as did lots of other

non-Turkmen Central Asian folks. This "Middle Amu Dyra" usage seems to

substitute a likely geographical attribution for the more frequent tendency

since the 70s to make attributions in terms of tribes. Apparently, the Amu Dyra

polygot is still too rich to sort out, although the indicators for including

something in it are not entirely clear to me. (I have jokingly suggested that is

it suspeciously close to such usages as "Shiraz" for south Persian rugs or even

to "Bokhara" (horrors!!!) for Turkmen ones. I am not at all sure that "Middle

Amu Dyra" is a good move. It changes the base indicator without seeming to offer

much evident advantage.)

So part of the reason I do not respond to many

images that might seem to have designs on them similar to some on my piece is

that I'm trying to go as far as I can go with the structural factors first,

since I think they are more stable.

Another reason is that my own

tendencies to see design similarities are quite closely restricted, and lots of

folks here see useful comparisons far more broadly than I do.

I think we

have to be careful rather than adventurous with design comparisons. At some

point nearly everything can be said to be similar, on some basis, with nearly

anything else and when that occurs one of the chief functions of comparison (to

distinguish) evaporates.

That is not to argue that my own view is

correct, only that it is different.

On the other hand I have not, in this

analysis, entirely ignored design factors.

I have referred explicitly to

the yellow ground minor meander border, acknowledging that it is often seen to

be a nearly signature Ersari usage. It does not in this instance seem to be

supported by the knot count indicator, but some might argue persuasively that it

may strongly suggest that this piece was woven in the Middle Amu Dyra area where

the Ersaris predominate. If that is accepted, the question becomes (always

probablistically) what group that we know was in the Amu Dyra is the best

candidate to have woven it and why do we think so?

I also treated the

"elem ends" seriously as possible indicators of format (an

engsi).

Everything is an estimate based on one or more indicators. I'm

just seeking the best confluence of indicators I can find and a free form

comparison of design features does not seem particularly hopeful to me. But I

invite anyone else who wants to make such an argument.

Does that help

explain?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by James Blanchard on 10-09-2005 01:37 PM:

Hi all,

I hope you will forgive some more novice musings...

I recall a

discussion about an "Ersari" rug that I showed on Virtual Show and Tell in

January, 2005 (some might remember the discussion about stencilled numbers on

the back, and Vincent Keers' sleuthing through old log books in Amsterdam).

Based on Vincent's investigations, the rug was established to be from 1936 or

earlier.

Anyway, here are a couple of pictures of the rug

again...

The knotting on this rug is also asymmetric, open left. The warps are

ivory, with some depression. The wefts are brown. It is not as finely knotted as

John's, averaging 8.5h x 11v (approx. 90-95 kpsi).

Why might this be

relevant?

Vincent Keers made the following comment on this

rug...

"The white warps make it less Afghan, more workshop and maybe

Iranian (Turkman) production on demand."

Perhaps Vincent could

elaborate if he is looking in on this discussion, but if there was Iranian

(Turkman) production of "Ersari design" rugs with ivory warps and

asymmetric-left knotting....

James.

Posted by Walter Davison on 10-09-2005 03:23 PM:

Hi Mr. Howe,

Yes, thank you. That helps a lot, and that makes

sense.

But, ... you write that "..it's far more costly for a weaver to

change structural things than it is for her to weave a new design, so structural

characteristics tend to be more stable and to change more

gradually.."

OK, now that seems correct to me, the "far more costly"

part. But do we know, and I certainly don't, whether it was commonplace for rugs

of dramatically different designs, 50, 60, or a 100 years back, to be produced

by a village woman, perhaps in a tent, located at the end of a dirt track if any

track at all, to be made by a weaver who might and did ever switch designs? Can

we know this?

I confess zero experience in this area, but it looks to me

that this might be a tough question to answer with any great confidence. Could

you address this question for me? Has such design switching been

documented?

Thanks.

Walt

Posted by Steve Price on 10-09-2005 03:55 PM:

Hi Walter

As many of you know already, I'm pretty skeptical about the

supremacy of technique as a criterion for attribution. There are a number of

reasons for this, let me mention just a couple here.

1. Technical

criteria arose when it was noted that groups or rugs with similar designs,

layouts and palettes had common structural characteristics as well. That is, the

epistemology of the structural criteria is such that their basis is design,

layout and color criteria. There are exceptions aplenty, but in general, this is

accurate.

2. One route of design and layout diffusion was intermarriage.

A woman who married into a "foreign" culture was likely to weave with the

designs, palettes and layouts typical of her new culture. She was unlikely to

change the way she worked, though. If she learned asymmetric knotting as a

child, I doubt that she began knotting symmetrically after marriage. Thus, a

Chodor woman marrying into a Yomud community would probably wind up weaving

Yomud-like things, but with asymmetric knots open to the right rather than with

the symmetric knots more usual in Yomud work. In such cases, the structural

criteria would mislead attributions.

In fact, we recognize technical

variations within a community. For example, it is pretty much agreed that a

relatively small percentage of weaving done with asymmetric knots can be

attributed to the Yomud primarily on the basis of design, layout and

color.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-09-2005 06:45 PM:

Hi Steve -

You wrote in part just above:

"As many of you know

already, I'm pretty skeptical about the supremacy of technique as a criterion

for attribution."

My thought:

I don't know anyone who takes that

position. It seems like a kind of debating class technique that mistates a

position the better to oppose it.

My own sense is that the more frequent

claim is that structural indicators are often better indicators for making

attribution estimates, but few, if any, I think argue that they should be taken

alone or that design can never be a deciding indicator.

If design is to

be seen as the usually reliable basis for making attributions should we begin

again to suggest that What we now call Saryk or Tekke or Ersari or even Balouch

pieces with turreted similar looking "Salor" guls should be reconsidered, after

all, as likely instances of Salor weaving?

You say that the source of

technical analysis began when folks saw that weavings with similar designs had

similar structures. That surely happened, but it is also true that it began when

people also noticed that weavings with quite similar designs sometimes had

different structures.

Would you recommend in the current instance that we

examine minutely the similarities and variations in the various mina khani

designs posted here or that we could collect? And, if so, what might we conclude

from that?

My own position has always been that I tend to weight

structural factors more heavily than designs when attempting to estimate a

attribution, but it's not a one-variable "structure is supreme"

argument.

I think it happens that design indicators can be sometimes be

nearly conclusive. But even then design usually does not operate alone.

The first Turkmen chuval I bought, when I began to collect (somehat

more) seriously has guls that are identical to those on some Tekke chuvals and

has an asymmetric knot open right. There is a very similar piece here in the DC

area that is pretty clearly Tekke (Plate 30 in Mackie and Thompson, 1980).

So there was a chance that mine might be Tekke too until George O'Bannon

pointed out that there are no known Tekke pieces with the border that mine has,

but there are a goodly number of Yomut group chuvals that do and some Yomut

pieces have asymmetric right knots as well. So the design was conclusive as long

as the knot was not disqualifying.

Now this piece may still be part of

some as yet undefined Yomut group, but I have never, since learning that it's

border is not in the Tekke vocabulary, suspected that this piece is Tekke.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Tim_Adam on 10-09-2005 07:02 PM:

Hi Walt,

I think the fact that tribes copied designs from other

tribes, e.g. Balouch from Turkmen, or copied designs from city rugs pretty

clearly indicates that weavers experimented with new designs.

Steve,

I am not sure I understand your points against

structural analysis. Are you saying that structural features don't provide much

new information beyond design, layout and color criteria?

On your second

point, it is my understanding that inter-tribal marriages were extremely rare

among Turkmen. And how an inter-tribal marriage would affect a woman's weaving

style is highly speculative. Or are there any historical sources on

this?

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 10-09-2005 07:56 PM:

Hi Tim

Most of the time, structural information adds very little

beyond what can be said on the basis of design, layout and palette. If that

weren't so, it would be almost impossible to make an attribution on the basis of

an image on a monitor, and it is usually possible to do that with a very high

degree of certainty.

I don't know what the frequency of intermarriage was

between the Turkmen tribal groups, nor do I have any hard information about how

it affected their weaving when it happened. I doubt that anyone else has hard

information, either. It is generally assumed, though, that the technique a woman

was taught as a child went with her (in John's words, earlier in this thread,

"..it's far more costly for a weaver to change structural things than it is for

her to weave a new design ..."). The conventional wisdom seems to me to be

likely to be correct in this case.

Hi John

My wording was poor in

saying that some consider technical criteria to be supreme. But I think it is

accurate to say that most collectors and dealers give the nod to technical

factors when faced with a dilemma.

The Belouch pieces with turreted guls

would never be mistaken for Salor work despite the superficial similarity of the

guls, even in a photograph where technical information was absent.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-10-2005 06:39 AM:

Hi Steve -

You wrote in part:

"...The Belouch pieces with

turreted guls would never be mistaken for Salor work despite the superficial

similarity of the guls, even in a photograph where technical information was

absent."

My thought:

You alertly pick the weakest point in my

comment, but I think you know from some pieces you own yourself that Belouch

weaving can be formidable.

You have in fact suggested that this piece of

mine might well be Belouch, despite its also looking much like Turkmen weaving

to some of us.

Now it is true that the mina khani design likely has

Persian roots and that both the Turkmen and the Belouch are weaving it "second

hand" so to speak. So maybe it is not a good test of whether a Belouch rendition

of some Turkmen devices might deceive looked at at the design level alone.

But I happen to know of one piece (a torba with two large turreted

"Salor" guls on it) in a major collection that has (admittedly after some

alternative considerations) been attributed to the Belouch. The chief

alternative considered was Afghan Ersari.

So it's not always easy once

one starts down the slippery slope of suggesting that designs are usually

adequate for attribution decisions.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-10-2005 07:24 AM:

Dear folks -

Several of us have offered suggestions about who might

have woven this piece and we have in the process explored a number of indicators

that might be used to determine this.

Perhaps now I should indicate what

the person from who I obtained this piece thought it likely is. We've had

several exchanges and I'll give you his actual language as closely as I

can.

First, I should say that this dealer is a long-time student of

Balouch weaving and hasn't suggested at any point in our conversation that he

thinks that this piece might have been woven by Balouch weavers. That for those

with that suspicion.

But here is what he thinks this piece likely is.

First his description of it:

Materials: wool with camel wefts (ed. I

can't detect this)

Structure / Technique: pile, asymmetric knot open

left

Condition: Poor

Comments On Condition: low pile, holes,

skinned areas, fold wear, and hardened skid inhibitor on the back.

Full

Description: wrong dimensions for an engsi, perhaps a funerary rug? Good age and

great color.

Next he draws on these indicators and some knowledge of his

own to make an attribution argument:

"Here is a sketch of my reasoning.

"Early Russian maps and two German travelogues mention a group of

Arabatchie situated near the Ali Eli in the south middle Amu Darya region.

"This group was connected with the main Aral group until the Khan of

Khiva again became powerful.

"Part of his policy was to divide and remix

the Turkoman tribes in his realm to keep them from forming alliances that might

jeopardize his power. Isolating the southern Arabatchies was part of the

program.

"I have encountered a number of weavings from this Amu region

that have a thin, long, knot almost identical to the Salor knot, though not

depressed. These weavings are open left.

"Rarely is cotton seen in them

but then cotton wasn't grown down there...only in the north.

"Since only

three tribes use this type of knot (ed. he means this long, thin shaped open

left knot); the Salor, early Imrelli ("Eagle"), and the Arabatchie, I strongly

suspect that pieces similiar to the one you are interested in are from the

latter tribe.

In a subsequent message he added:

"I don't think

that the south/middle Amu Darya group has cotton. I don't think I've ever seen

it in their wefts and only once or twice, in exceedingly small amounts, I've

seen it as pile.

"The thing is, that they were there and the knot you

see in these weavings is the same sort of long, thin knot that we see in their

northern cousins."

So there we have this dealer's thoughts. He works with

his knowledge of the history of the Amu Dyra area, including who was where when.

What moves the local politicos made that could have affected tribal movements.

He has an explanation for the seeming absence of cotton (usually an Arabatchi

indicator) and he hangs his argument heavily on both the character of the knot

and its width and shape.

Do you find this argument convincing? It seems a

little tenuous to me, but it's interesting.

Further frank comments are

invited.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-10-2005 07:24 AM:

Hi John

Your concluding remark, which I think is the "take-home"

message in your post, is "So it's not always easy once one starts down the

slippery slope of suggesting that designs are usually adequate for attribution

decisions."

You're right, it isn't always easy to make

attributions with confidence on the basis of designs, layout and palette (I

don't think I ever suggested that designs were sufficient; I surely don't

believe that they are). But this doesn't negate the fact that designs, layout

and palette are usually adequate. And by "usually", I mean, more than 99%

of the time. That is, I think less than 1% of the antique rugs and related

textiles from western and central Asia present attribution difficulties that

require more than a photo of the front of the piece. Indeed, the most common

practice is to make attributions by comparing one or more photos of the piece

with photos in published sources.

As a related side issue, there has been

a recent exchange of unpleasantries on line between two self-proclaimed experts.

The dispute was whether one of the rugs offered at a recent major auction was

made in Talish (as catalogued) or somewhere else in the Caucasus (I don't

remember whether the proposed alternative was Genje or Karabagh, and it doesn't

really matter for this discussion). My recollection is that neither "expert" had

handled the rug or even seen it in the wool (although the auction house person

who wrote the catalogue entry had, obviously), and the debate revolved entirely

around design. Neither party even raised the question of supplementary wefts at

the edges, a feature nearly universal to Talish textiles and nearly unique to

them. In that instance, a techical detail could have resolved the question to my

satisfaction, although it got pretty well narrowed down by the color

photo.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-10-2005 04:21 PM:

Arabachi? = Ersari Type?

Hi John ,Steve, All

It seems, as I had expected, that this rug does

not clearly fall into any specific category. Looking back I noticed I had failed

to make my attribution, but as the content of my post suggests, I had assumed it

to be of the Ersari Type.

I had arrived at this conclusion based upon the

color, especially of the yellow ground "judor"border (granted I had suspected

that I might have been camel hair), and the design in general, which has much

affinity with the Ersari chuval depicted. True, the petal arrangement may have

been of the Belouch ( bearing the scope of my experience in mind  ) but that double judor

border says Ersari to me. For what it's worth, I think we would do well to

consider attribution as a process proceeding from the general, as in color,

design and materals, to specifics of structure.

) but that double judor

border says Ersari to me. For what it's worth, I think we would do well to

consider attribution as a process proceeding from the general, as in color,

design and materals, to specifics of structure.

If find this study of the

history (and topography) of the Amu Darya fascinating for it's implications

regarding Turkmen weaving.

Oops, gotta run, will continue this line of

inquiry in a while.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-10-2005 05:41 PM:

Amu Darya as Pipline of Commerce

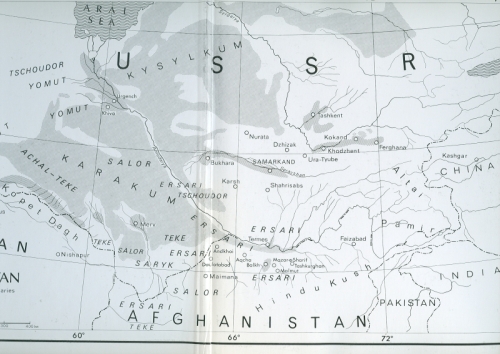

Hi John. All

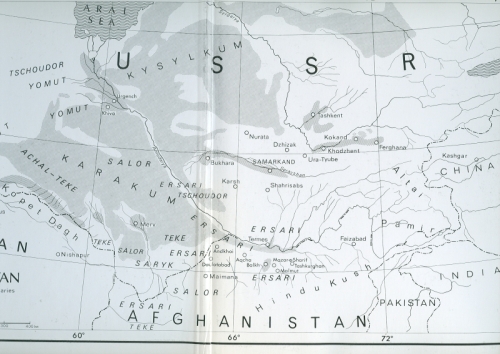

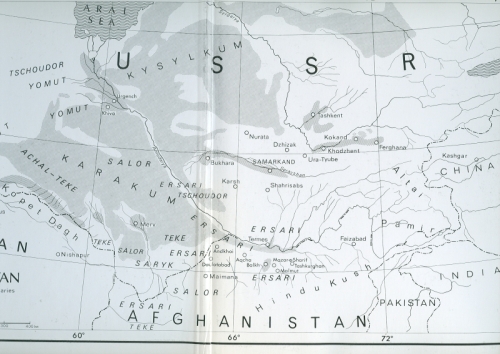

Find below a map of the Turkmen regions from Khalter's

"Art and Crafts of Turkestan",

making note of it's origins in the Pamir mountains, it's passage through

the desert and adjacent to Bokhara in the middle region, and it's terminus as a

delta feeding the Aral Sea. The following is a brief synopsis of the Amu Darya

from Encarta.

Amu Darya (ancient Oxus; Russian Amudar’ya; Turkmen

Amuderya; Uzbek Amudaryo; Tajik Dar”yoi Amu), largest river of Central Asia. The

Amu Darya is formed by the junction of the Pandj and Vakhsh rivers in the Pamirs

mountain region, on Tajikistan's southwestern border. The river measures 2,540

km (1,580 mi) in length. It follows a northwest course between Tajikistan and

Afghanistan, continues northwest between Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, and then

flows north through Uzbekistan into the Large Aral Sea (Russian Bol’shoye

Aral’skoye More), which separated from the northern Small Aral Sea (Russian

Maloye Aral’skoye More) in the late 1980s. The Amu Darya’s main tributaries are

the Panj and Vakhsh rivers, which both rise in the Pamirs. The Panj forms part

of the boundary between Tajikistan and Afghanistan, and the Vakhsh flows through

southwest Tajikistan to join the Amu Darya at the Afghan border. Since the 1950s

the Amu Darya has been heavily tapped for irrigation, which has greatly reduced

its water level and the amount of water reaching the Aral Sea. During the 1980s

several years passed in which little or no water reached the Aral Sea from the

river. Inflows from the Syr Darya River, which empties into the Small Aral Sea

from the east, have also drastically diminished in recent decades. As a result,

the volume of the Aral Sea dropped by about 80 percent between 1960 and 1996.

The largest single cause of the decline in the Amu Darya’s water level is the

Garagum Canal, the longest canal in the former Soviet Union and one of the

longest in the world. Near the town of Oba the canal diverts water from the

river at the rate of about 12 cu km (about 5 cu mi) per year—about one-ninth of

all the water diverted in the Aral Sea basin. Reduced water flow has restricted

water transportation on the Amu Darya, which was once navigable for light draft

vessels over nearly half its length. The lower reaches of the river once

contained a large delta that supported extensive vegetation, but most of the

delta has dried up due to reduced water flow. Over the centuries the river has

shifted its course several times. In the 3rd and 4th millennia bc the Amu Darya

flowed westward from the Khorezm Oasis into Lake Sarykamysh, and from there to

the Caspian Sea. From the 17th century until the 1980s the Amu Darya emptied

exclusively into the Aral Sea, except during periods of intense flooding, when

overflows went into Lake Sarykamysh.

For now let's concentrate upon

the rivers signifigance as a major conduit for the transportation of goods and

products in the Turkmen regions, being the largest river of Central Asia, and

some possible implication for the carpet industry. I would assume that the river

could/would have been used to move raw carpet materials, such as wool and

dyestuffs, as well as carpets, along the middle and lower reaches of the Amu

Darya, which are nagivable by larger commercial vessils, and possibly the upper

extremity in which rafts might be plied ( as they are on some other mountain

rivers in this area). All conveniently leading to Bokhara.

In a

contemporary thread here on Turkotek Significance of color variations we are discussing the origins

of yellow dyes( among other things), and in the process came across a discussion

of the yellow dyes in Turkmen carpets in the Whiting essay in the back of the

Textile Museum's "Turkmen"

"Seems the primary suspects in Turkmen

weaving (at the time of printing) are isparuk (Delphinium sulphureum), which

grows wild in Afghanistsan, and weld (Reseda Luteola L.) which is an

"essentially cultivated plant. Tekke rugs, both older and newer, which "retained

a good green" demonstrated properties of weld dyes, and those exhibiting this

green "fading out to blue", of isparuk. Conclusion? First, isparuk is prone to

fading, and weld more fast. Second, that isparuk was rarely "less than an

important ingrediant except when replaced by weld.". And third, the weld was

obtained from setteled people with which the Turkmen were on good terms. Now

under what conditions and hence locations does one grow weld?"

What does

all of this mean? In short, that dyes, wool and rugs could have been shipped

along the middle and lower Amu Darya with ease, possibly facilitating the

transmission of design patterns (between Yomud and Ersari) and color selections

(especially that of this cultivated Weld) in both directions, up and down river.

From the upper extremity of the Amu Darya, transportation would be one way, from

higher to lower elevations,say from Mazar-e Sharif or Andkhoi (and hence these

indigenous Ersari patterns and color schemes) to Bukhara and points

north.

Now for this transmission of design from Ersari to Balouch, I

submit the following, from the Middle Amu

Darya weaving thread here on Turkotek.

Dave

Posted by Tim_Adam on 10-10-2005 06:39 PM:

Hi John,

I am a little lost now. From what I could gather it is only

the relatively high knot count and the dealer's opinion that speak in favor of

an Arabatchi attribution. Or am I missing something?

I find it rather

unconvincing to rule out an Ersari attribution based on a knot count that it is

higher than the range provided in Loges' book, especially since there are other

indicators that speak pretty strongly in favor of Ersari. After all, Loges'

range is based on a relatively small sample of rugs. And the color scheme of

your rug is completely different from any piece I have seen that has been

attributed to the Arabatchi.

Tim

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-10-2005 10:05 PM:

Hi Tim -

The attribution of this piece can definitely still be

debated.

I think most people would be tempted to say Ersari on the basis

of the yellow ground minor border alone, since that is seen as signature

Ersari.

It is true that Loges offers only three Arabatchie pieces, but

the knot count in mine centers nicely in their range and you are welcome to find

and cite Arabatchie's that do not. And most Ersari pieces are quite a bit

coarser. Most are in the 50-60 KPSI range and the center of the admittedly quite

wide range of Ersari pieces is quite a bit lower than that indicated for

Arabatchis. So I think the knot count difference is not something to be ignored

quickly.

Lots of Arabatchie's are pretty ugly, but some (look at the

famous Ballard chuval in Mackie and Thompson, Plate 54 and some of the examples

Jourdan offers, Plates 202 ff.) can exhibit better, clearer reds. So a better

color palette isn't necessarily disqualifying.

The lack of cotton in the

structure is a departure but this dealer offers a plausible (who can say if it

is true?) explanation for holding on to his Arabatchie attribution despite its

absence.

I also think this dealer's noticing the shape, length and

thinness of the knot nodes and what other knot nodes resemble them pretty

careful and sophisticated.

Now, if you insist on seeing this piece as

Ersari rather than one made by lower middle Amu Darya Arabatchies, look at

Jourdan's indication on page 228 and Elena Tzareva's parenthetical comments on

all of her Arabatchi pieces. As Jourdan notes, Tzareva explicitly indicates that

she sees Arabatchis as a part of the Ersari group. That might make this dealer's

Arabatchie assertion less difficult to accept.

You can have your

attribution cake and eat it too.

Last, let me play Steve's design-guided

attribution game a bit, but in a way he probably wouldn't accept.

I own

a few Ersari pieces, including one chuval fragment with a mina khani design and

lots of silk pile decoration. One thing that struck me about this piece I have

just bought is that it didn't quite "look" Ersari to me. Spooky, huh? And maybe

wrong.

Examining my feelings, I noticed that there are odd things about

the drawing of the mina khani field in this piece. The drawing "decays" a bit at

the sides and there is an odd drawing of some of the central mina khani

elements. And although David Hunt supplies some instances of rather stiff

drawing in Ersari elems, the overall effect of the drawing in this piece had a

kind of stiffness about it that I experience as stately rather than just static,

and distinctive from what I see in Ersari drawing (I suspect this latter is part

of what people who said "maybe Balouch" are seeing too). Now do any of these

"doesn't look quite Ersari to me" feelings indicate that it is Arabatchi

instead? No.

Maybe I should just say that I suspect that it was probably

made in the Amu Darya area (minor border and asymmetric open left knot), but

that it doesn't quite look Ersari to me.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by James Blanchard on 10-10-2005 11:11 PM:

Dear John,

This Discussion is living up to its name... quite a puzzle.

The explanation from the dealer seems to point to a particularly idiosyncratic

attribution construct that will continue to frustrate those of us who like to

master information, and will delight those of us that still like a bit of the

unusual!

Regardless, I very much like the rug.

But I do have a few

residual questions that are based not on expertise in this area, but rather on

some personal observations about the deductive process for attribution.

Please forgive me for dragging us all back to my "stencilled Ersari",

but I think it is relevant since it does seem to share some features with yours.

It has design features which could really only be called "Ersari". In my hands,

the colours and wool seem to be of very high quality. It has ivory wool warps

and brown wefts (wool, I am persuaded). The knotting is asymmetric-left and

finer than is usual for Ersari, though certainly not "out of range" like yours.

I really don't know what is meant by the characteristic "long thin knots"

mentioned by the dealer, so perhaps you could elaborate for my benefit. I do see

similarities between the knotting on your rug and mine (especially looking at

the yellow knots in yours). I don't know the exact age of mine, but although its

condition is "nearly mint" it is not "new", having been sold once in 1936. You

haven't mentioned an age estimate for yours. One last similarity -- I purchased

it from a dealer who has quite a bit of experience in the region, and held the

rug in high regard (mostly for the high quality wool and colour). He even nailed

the "stencil" date right on the head. He attributed my rug to the Ersari, though

he felt that the structure and particularly the size and shape were out of the

ordinary.

In discussing my rug, only one person offered a "non-Ersari"

attribution. Vincent Keers suggested "Iranian (Turkman) production on demand". I

am certainly in no position to refute or affirm that assessment. I have since

simply considered it an "Ersari" rug based on design, if not

attribution.

I have never entertained a "Middle Amu Darya Arabatchi"

attribution for my rug. Should I now? If not, why

not?

Cheers,

James.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-10-2005 11:36 PM:

Arabachi vs Ersari Part II

Hi John, Tim All

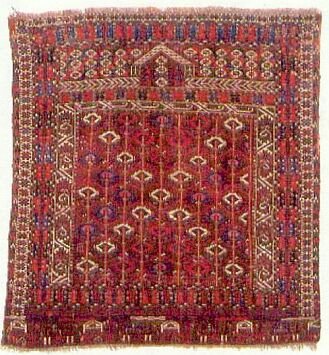

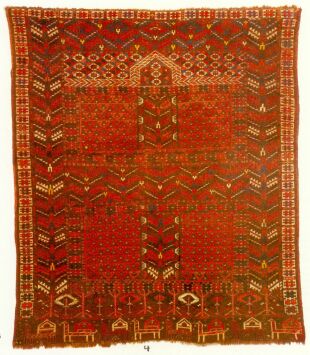

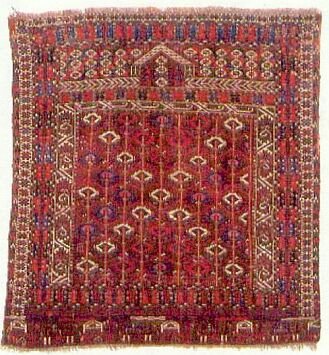

I just noticed that we have not one image posted of

an Arabachi weaving, so witness the following Engsi, Plate 205 from

Jourdan

and the next, from Turkotek's The Turkmen Engsi :

Doorway To Paradise salon.

Followed by the rug

in question.

Jourdan makes some assertions regarding Arabachi weaving

including;

1) very distinctive weavings

2) asymmetric left

knotting and wool/cotton plied wefts as sine qua non

3) ribbed backs and

scattered flecks of white cotton

4) "camel train" in elem typical for

Arabachi engsi

and to judge from what we have seen so far, it fails on

most counts.

Or does it? We do have this tenuous yet plausible

explanation for the absence of cotton (besides, I wouldn't be suprised at the

occasional Arabachi sans cotton in the wefts, experience suggests weavers simply

use whatever is available), and a close proximity to a tribe notorious for their

use of this "Judor" border, the Ali Eli ( Jourdan also cites the kochak border

found in Arabachi plate #204 as an Ersari usage). Number of colors seems about

right, and their does seem a kindered use of color in regard to the engsi above.

Yet the open left vs. open right knot structure,while a rather striking

departure from the "typical" (whatever that is  ) Ersari, is hardly

unknown. Maybe this is much of the problem, our inability to further qualify and

quantify our definition of Ersari. If not for the existence of considerable

numbers of high Kpsi open right Ersari, I would be inclined to find this high

Kpsi characteristic in of itself more persuasive. And of course the Arabachi

are, or in the least some authors contend, Ersari.

) Ersari, is hardly

unknown. Maybe this is much of the problem, our inability to further qualify and

quantify our definition of Ersari. If not for the existence of considerable

numbers of high Kpsi open right Ersari, I would be inclined to find this high

Kpsi characteristic in of itself more persuasive. And of course the Arabachi

are, or in the least some authors contend, Ersari.

For myself it really

fails the engsi qualification, as both the dimensions and design don't to

conform to the standard (in the least to that degree with which I am

familiar ).

Now these dimensions,which I think worthy of further comment, say as much about

this piece as does the use of the mina khani field, and both point me toward

modern as opposed to traditional production. The size strikes as more the 4x6

area rug, and I strongly suspect that, as Steve stated earlier, the outer

"judor" guard border is missing. The mina khani field seems a standard of modern

Turkmen production, as a visit to the local flea market will attest, so the

size, combined with the numerous borders and what strikes as a more modern field

design says to me early commercial production. Early as in 19th century

).

Now these dimensions,which I think worthy of further comment, say as much about

this piece as does the use of the mina khani field, and both point me toward

modern as opposed to traditional production. The size strikes as more the 4x6

area rug, and I strongly suspect that, as Steve stated earlier, the outer

"judor" guard border is missing. The mina khani field seems a standard of modern

Turkmen production, as a visit to the local flea market will attest, so the

size, combined with the numerous borders and what strikes as a more modern field

design says to me early commercial production. Early as in 19th century

It does seem

to share several characteristics with the Arabachi, and I wouldn't argue with an

Arabachi? designation (rememberimg that I am proceeding from photographs  )but just as the

design somehow doesn't "look " Ersari, if the design was a little more

traditional I would be of greater inclination to designate as Arabachi. Or

perhaps a hybrid?

)but just as the

design somehow doesn't "look " Ersari, if the design was a little more

traditional I would be of greater inclination to designate as Arabachi. Or

perhaps a hybrid?

Dave

Posted by Steve Price on 10-11-2005 06:04 AM:

Hi People

It might be worth reminding ourselves that attributions are

rarely statements of fact, but statements of probabilities. Sometimes the

probability of a particular attribution being correct is high enough to leave us

comfortable ignoring all alternatives.

Clearly, this rug is not in that

category. It has lots of Ersari characteristics, but some that are atypical for

Ersari. The dealer who sold it is able to present arguments for Arabachi origin

that, while not compelling, are at least plausible. In the absence of anything

more concrete than the fact that someone regarded as an expert on Belouch

weavings didn't mention Belouch among his possible attributions, I see no reason

to eliminate Belouch as an origin. The Belouch wove so many Turkmenoid rugs

that, until fairly recently, many collectors thought the Belouch weavings were

all derivative.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 10-11-2005 06:39 AM:

Hi All,

For me this John Howe rug is just a normal Ersari ( Beshir,

Amu Darya ) rug.

The fineness of the knotting and the openness to the left

does not contradict at all with a Beshir attribution, while the design and

especially the colors are so Beshir as Beshir can be.

The speculation

that it could be " Arabatchi " or " Baluch" is in my opinion hilarious

speculative and seems in essence based on a mythical " long, thin knot

".

Would love to see one,

Best regards,

Rob.

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2005 08:00 AM:

Hi James -

You ask first should you reconsider the indications you

have been given and your own impression that your piece below is

Ersari.

I

think not. All of the design features in your piece are part of the Ersari

vocabulary, the knot count is lower and there are some Ersaris with an

asymmetric open left knot.

You also ask for a better description of what

is being pointed to when this dealer says that the knot is "long and thin" and

resembles closely the shape of the knots not only in northern Arabatchie

weavings, but also some "eagle" group pieces and the Salors (although he makes

clear he is not considering a Salor attribution at all).

And such a

description may be useful because Rob van Wieringen sees this dealer's rationale

for his attribution "hilariously speculative" and depending too much on a

"mythical ' long, thin knot ' ".

Now I think this attribution is a shade

aggressive and it is visibly speculative, but I think we should refrain from

doubling over in laughter about it.

Knot node size and shape are an

established aspect of technical rug analysis. The characteristics of knot nodes

are a part of "weave pattern" proposed and discussed seriously by Neff and

Maggs, in 1977 in their "Dictionary of Oriental Rugs."

Although used

widely by dealers and people in the trade (they will frequently quickly look at

the back of a piece and say, often with surprising precision, where it was

likely woven) it has not caught on much yet with rug collectors and scholars

(you do not often see descriptions of knot node shape in even quite detailed

technical analyses; it does not, for example, earn a place on Marla Mallett's

guides for analysing pile rugs) but one does sometimes hear reference to it by

experienced people.

But some authors have taken it seriously enough to

begin to supply images of the backs of their rugs (Willborg's and Runge's

catalogs on Hammadan are the readiest examples but Neff and Maggs presented a

number of examples in 1977).

My own view is that there is likely

something to knot node shape and size as an attribution indicator, but that we

just haven't been looking at it long enough for the differences to be recorded,

systematized and related to other attribution indicators that we use. But there

is nothing "mythical" about the shape and size of a rug's knot nodes. They are

very much "there" if you want to examine them.

But to try to answer

James' question about what is a "wide, thin" knot. And why might its presence

supply less than laughable support for this dealer's attrubtion

estimate?

When a weaver ties a knot around two warps, she is doing so

with a strand of wool that (not to put too fine a point on it) has a given

width. That this width can vary seems beyond debate. After a row of knots has

been completed a weaver beats them down with a comb tool. Then one or more wefts

are added with additional beating after the insertion of each one. The heaviness

and intensity and length of time that this beating goes on compresses the (now

tied) knots in varying degrees. That this compression will also be a variable

also seems to me beyond debate.

The result of such variations is that

when one looks (closely) at the back of a pile rug one will be able to discern

(even if magnification is needed) what the shape and size of the two knot nodes

that together make up each knot are.

When we looked at my my

yellow-ground Caucasian wreck in another thread here I joked (but also not

quite) that I might hang a Kazak attribution primarily on the fact that knot

nodes looked to me more than twice as high as they are wide. I was drawing on

the indication by Neff and Maggs that one of the main features of Kazak weave

pattern is that Kazak knot nodes are visibly much taller than they are

wide.

What this dealer has noticed is something like the reverse of

that.

He says the knots are wide and thin. That is, the wool strands used to

make them were noticeably narrow and/or have been tightly packed down by

beating. This results in a knot node that is quite short vertically. He also

notes that the knots are wide. This is a function of the size and the closeness

of the warps. The resulting shape he is talking about is one in which each knot

node is wider than it is tall and this sense of width is accentuated when one

looks at the two knot nodes that comprise each knot.

Now Rob's laughter

about this suggestion has been functional for me because he made me look more

closely at what Neff and Maggs say about their two Ersari examples (they offer

an "Afghan" example and a classic "Beshiri" prayer format). Here is their

description of both of these Ersari knot nodes, which they explicitly say are

the same. "On the vertical line, the nodes of the asymmetrical knots are longer

than they are wide."

Reading this description of Ersari knots side by

side with this dealer's description of my just purchased piece I want to

suggest, however modestly, that the knot nodes on mine are different precisely

in that the individual knot nodes are wider than they are tall and the tallness

itself is quite short. This dealer's description of this lack of height as

"thin" seems appropriate.

Now this is just one factor and this dealer's

attribution is, I think, still very much in debate, but the knot node size and

shape on my piece, ARE different from what Neff and Maggs say is more typical

for Ersari pieces.

I have two last questions for Rob.

Please give

me your indicators for a "normal Ersari (Beshiri, Amu Darya)" rug?

Do you

not distinguish Ersari from Beshiri, and if not why do we need two

terms?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 10-11-2005 11:46 AM:

Hello John,

I am sorry if I upset you by my remark; it wasn't my

intention.

Of course knot nodes are there and there variety of forms is

something not to neglect when studying rugs etc.

My point of view, however,

is that the colors and the design in this rug are allover Beshir ( as part of

the Ersari-group, settled in the Amu Darya valley ) and rules out any other

possible attribution. For me especially the colors, as seen in the close-up, are

a very convincing indicator.

The focus on a supposed abberation in knot node

form ( and at the same time neglecting strong indicators as colors and design ),

seems to me a very thin line to attribute otherwise.

It is like a dog

with six legs : I would call it a dog with six legs, but I get the impression

the rationale of the dealer would make him to call the dog a "possible

spider".

In my opinion your rug is a 19th. cent. Beshir with long, thin

knot nodes.

Regards,

Rob.

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2005 06:26 PM:

Hi Rob -

We don't get "upset" per se much here on Turkotek. We do

engage in vigorous debate, if we feel that is called for. But the future of

civilization does not rest on the outcome of our discussions here so no harm is

usually done.

You are not alone in insisting that this piece is Ersari. I

have Americans traveling in Europe writing me on the side to say

that.

But those claiming most vigorously that the color palette and

designs indicate pretty conclusively that this piece is Ersari (and it might

well be) are oddly elliptical.

Their conclusion is firm, but the

evidence on which it is based is described in a conclusionary way without

showing itself for examination.

What is a "typical Ersari palette?"

What are the "typical Ersari designs?" (I'll give you the yellow ground

minor border.)

Some recognitions are beyond language, but we should at

least try.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by James Blanchard on 10-11-2005 11:08 PM:

A picture's worth...

Dear John,

Would it be possible for you to post a clearer (brighter)

picture of the knot nodes of the "long, thin knots"? Since I am sure that many

Turkotekkers have a variety of Ersaris in their own collections it might help to

assess how extraordinary the knotting technique on your rug

is.

Regards,

James

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-12-2005 02:33 AM:

City Dye, Country Dye

Hi Folks

Is it just me, or does the yellow in John's rug seem lacking

in intensity for an Amu Darya or Beshiri weaving? I had suspected it might be

camel hair, to tell the truth. I don't know, the colors overall seems a little

murky for above said.

It seems that misperception often proceeds from the confusion

of weaving habits of the past with those more recent. As an example, I had

noticed a passage ( from the T.M.'s "Turkmen" I believe), which had asserted

that the mina khani pattern is frequently seen in Amu Darya weaving, which is of

course true, but does not negate the fact that in more recent times this field

pattern has figured prominently in the repetoir of Afghan Ersari (hence upper

Amu Darya) weaving. Perhaps a characteristic by which one could distinguish

between the two is the quality of and use of color? I see this confusion

regarding the habits of older weaving culture and the more modern in our

discussions constantly.

Dave

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-12-2005 11:21 AM:

Dear folks -

I have received, on the side, two email messages from

Richard Isaacson.

Richard, some of you will know, is a serious collector

and student of Turkmen and other Central Asian materials, and has, explicitly

now, undertaken some scholarly study of them.

He has given me permission

to quote what he said.

Richard:

"You might be interested to hear

that ALL Mina Khani pieces of this design group that I have ever seen have knots

which are asymmetric, open left. This applies to 18th and 19th century main

carpets as well as bags.

"The colors couldn't possibly be Arabatchi or

Salor. This is an as yet unidentified Middle Amu Darya group, usually lumped in

with the Ersaris in most books.

"Elena's forthcoming book may attempt to

sort this out."

Then in a subsequent email he adds:

"As far as the

colors go, I am guessing from pictures. However, Arabatchis have distinctive

orange-reds and other bizarre shades. Your piece looks like it has more

conventional color tones."

My thanks to Richard for these informed

indications.

The first seems an instance of what Steve Price pointed to

when he said that one way in which structural analysis began was that folks

looked at particular designs and noticed that they often coincided with

particular structural features.

And Richard is more specific about why

he estimates that the color palette on my piece is unlikely to be one chosen by

Arabatchi weavers.

He also confirmed in this second message that the

Elena Tzareva book on Beshiri weaving to which he referred is the one on which

she began work with Robert Pinner. It's been in the works for a long time. (She

was at Pinner's actively working on it with him when my wife and I visited

Pinner in (I think) 1999.)

Regards,

R. John Howe

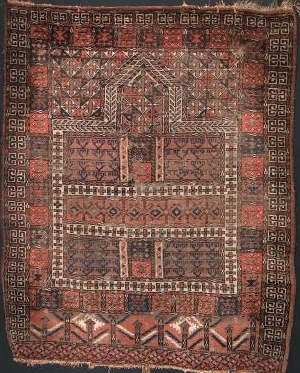

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 10-12-2005 01:46 PM:

Great Minds Buy Alike

Hi John, et all,

You are not alone, John. Recently (very

recently, but before this thread was started), I acquired a mixed heritage piece

with a Turkoman design having the following characteristics (some in

common with Johns piece. Note: no cotton anywhere):

Size: 63 in. X 52

in.

Warp: Z4S, Almost all handspun ivory wool, occasionally a warp is

comprised of mixed handspun gray & brown wool.

Weft: Z, Three thin

shots Z-spun undyed handspun brown wool. The yarns are not plied. There is

little no warp depression.

Pile: Asymmetrical left, Z2S, Handspun wool,

various colors as in images. Knots: 7 to 8 Vertical, 7 Horizontal. Where intact,

the pile is 1/2 inch long

Selvage: Animal hair wrapped around 2 cords,

each made of animal hair and wrapped in the same undyed brown wool that was used

for the weft.

The seller postulated that this is a product of

Chodor/Baluchi intermarriage. I don't buy the Chodor connection; Chodor work is

typically open to the right. This piece is open left.

Here are the

images; The whole thing:

Front &

back:

Closeup of back 1; the thick weft layering allows for a largely

symmetrical knot layout:

Closeup of back

2; Knots were not always pounded down very well, leaving warps exposed in some

areas:

Closeup showing end of rug with warp & weft

detail:

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by James Blanchard on 10-13-2005 03:57 AM:

Tying up loose ends...

Dear John,

Thanks for sharing the opinions of Richard Isaacson. I have

a few residual questions, that perhaps you or Mr. Isaacson could

address.

1. Did this "unidentified Middle Amu Darya group" weave other

designs, and if so, would they be generally consistent with Ersari weavings in

terms of design and palette?

2. Are there other notable structural

features associated with this group (such as ivory wool warps, tighter knotting,

"long thin knots")?

3. What are your conclusions regarding the opinions

of the dealer (long thin knots = specific Amu Darya Arabatchi), who you

indicated also has quite a bit of experience in weavings from that

region?

I ask these questions mainly because I am still very much on the

steep part of the learning curve and I tend to like to extract at least some

"take home messages" from these types of discussions.

On the topic of

knot nodes, here are three different rugs that seem to differ somewhat, though

the knot counts are similar (8h by 11-13v per sq inch).... The first Ersari and

the Baluch do seem to have somewhat "thinner" knots than the middle

(ensi).

Cheers,

James.

1. Ersari (asymmetric left, 8h by

11-12v)

2.

Ersari (ensi) (asymmetric right, 8h x 11v)

3.

Baluch (asymmetric left, 8h x 13v)

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-13-2005 06:08 AM:

Dear folks -

There are at three posts above to which I should

respond.

Mr. Davison -

One of the things I do without exception

with a new piece is to put it for a time into a freezer to rid it of any

possible living moths and moth larva. The piece is now in that freezer which is

about an hour and a half from where I am typing. And while I have a digital

camera with great close-up capabilities, these can only be realized with a

tripod and timed, self-operated shots, something I have not yet equipped myself

to do. Close-up shots hand held are in my experience very chancy. But James

Blanchard has given you some examples to look at and if you can find someone who

has a copy of the Neff and Maggs book they provide a number of close-up pictures

of back in which knot node size and shape can be examined.

Mr. Blanchard

-

Richard Isaacson is not readily available for questions at the moment,

but the logic of the notion of a "as yet undefined group" does suggest that

there are likely other members. The problem with an undefined group is that

things are still generally murky about it and group membership and

characteristics might well be among them. I think Richard is acknowledging that

there may be things about this piece that might not let us group it with

complete comfort with many of the pieces we currently call "Ersari." I think he

is also acknowledging that the group we call "Ersari" is a very large construct

and we think it has (Yomut too) lots of parts, we just don't know yet what they

are.

This is what leads to such usages as "not Ersari" or "middle Amu

Darya." What this dealer of mine has done is to put a possible tribal name on a

piece that doesn't seem Ersari to him but that he admits seems likely to have

been woven in the "lower middle Amu Darya."

Richard is disagreeing and

cites palette (as others have here) as one basis that. He has done a better job

of describing than others so far why he thinks the colors exhibited by my piece

on his monitor are likely "not Arabatchie" but more within the range of pieces

we usually call Ersari.

He says that this piece lacks some "distinctive

orange-reds and other bizarre shades" that appear in Arabatchi weavings. The

darkish red ground of this piece IS more on the cherry side than on the "brick"

side of red and there are no greens or "off colors" (e.g. purplish browns) that

Arabatchis often exhibit. (I would counter that the Arabatchis are not unknown

to have produced pieces with clear reds and without off-colors. Plate 202 on

page 229 in Jourdan is one example.)

You ask about other features of the

"group" to which Richard refers and he does not define it really at all. And he

has not mentioned this dealer's claim about knot node shape and size, but that

may be one reason why he says it may be an as yet undefined Ersari

subgroup.

You usefully provide three examples of rug backs and say that

you think you can tell something about thinness from looking at these images.

Technically, the relative height and width of knot nodes would need to be

measured in order to be compared usefully and even my dealer did not offer such

measures. He's just looked a lots of rugs and knots for a long time and sees the

height of the knots in this piece as noticeably shorter ("thinner") than Ersari

knot nodes he has seen, and similar and shape to the knot nodes on two other

Turkmen tribal groupings he names. What we can do, looking at these images is to

describe the shape of the knot nodes. But we cannot reliably comment on their

relative size.

I would describe the shape of the individual knot nodes in

the top one as slightly wider than they are tall. The second piece down seems to

me to have knot nodes that are somewhat wider in proportion to their length than

the top example. The third piece seems to me to have knot nodes that are the

closest to square although they, too, may still be slightly wider than

tall.

Now about my opinion of this dealer's attribution of this piece, I

think I have already given that. He is known to be aggressive in his

attributions and is often quite alone. I think it very alert of him to have

noticed that what he calls the "thinness" of the open left knots and to have

mobilized it (coupled with some history) in an argument for distinguishing this

piece from Ersari weavings with open left knots. He is tentative rather than

dogmatic about his attribution and has clearly noticed the color pallette of

this piece because he describes its colors as "great."

I think it an

imaginative suggestion and argment (nearly all the Turkmen tribes WERE in the

Amu Darya at one time or other) but I have no way of telling whether he is

right. He could be dead wrong (he still actively supports Jon Thompson's

"Imreli" attribution that Thompson himself has withdrawn) but I like very much

his invocation of knot node. I think it is a variable that we haven't looked at

much yet in technical analysis but that might sometimes help us sort some things

out.

Chuck -

I would guess that your engsi with a hatchli design

is most likely Balouch, but might also be (because of its open left knot) a

younger Yomut piece woven by the groups who wove the "eagle" pieces (none of the

"eagle " pieces, I think, are estimated to have great age, i.e. before 1850).

There are no reds in this palette and I have seen both Baluch and Yomut pieces

with this sort of brown. There seems also some hard camel hair used (selvege?)

and if so that would be a strong Balouch indicator.

Just to demonstrate,

though, that the world is not tidy, compare the border that surrounds the

hatchli panels on your piece with the one that occurs in the same place on an

Arabatchi (Plate 205) in Jourdan's Turkmen volume, page 232. I can't really see

yours but they look possibly very similar. I'm not suggesting remotely that your

piece might be Arabatchi, only that the world of attribution estimating is

rather messy in some respects.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 10-13-2005 07:27 AM:

Hi John,

With all respect John I think you make things more

complicated then they are.

You pick out single elements in this Chuck's rug,

such as a certain present brown color, open left knot and a single design

element to refer to Yomut, Eagle and Arabatchi ( and what about the lower tree

panel : Tekke? ).

I think this is unnecessary confusing. Design is fluid and

much more affected by the individual interpretation of the weaver.

The main

indicator, for me at least, is the total color palette of the first close-up :

it reveals clearly this is a ( Ensi inspired ) Baluch, and nothing else.

Now you will ask, as you did before : what is a typical Baluch

palette?

To be honest I am not able to put that in words. I can only say,

well this is, as with the Beshir.

I think it is wiser to let the colors

speak, then trying to catch them in slippery

words.

Regards,

Rob.

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-13-2005 07:45 AM:

Hi Rob -

You may be right.

I asked myself (although the hard

camel hair edges don't fit at all; but I can't tell if they are that in Chuck's

photos) what kind of piece could have an open left asymmetric knot and this

brown without red palette?

I mentioned Yomut (although I don't think it

likely) because there are Yomut pieces that meet those two tests and it's

important to eliminate that possibility, at least. (And the hard camel hair

selveges do that, if that's what they are.)

And the Arabatchi reference

was not (as I said) to suggest anything about what this piece might actually be.

It was only to signal that a rather infrequent border seems to be present and in

the same location on both Chuck's piece and on an Arabatchi engsi.

I

take it as a sign that design indicators are very messy

indeed.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 10-13-2005 09:01 AM:

quote:

Originally posted by R. John Howe

I take it as a sign that

design indicators are very messy indeed.

Hi John

Right, design indicators are messy and unreliable in

the absence of other criteria for attribution. If layout and palette are

included with design, the combination is almost 100% reliable. That is, they

will lead to a reasonably specific attribution in terms of geography (or tribe)

and date of origin of almost every piece to which they are applied, and nearly

all collectors and "experts" will agree that those attributions are correct.

Whether the attributions really are correct, of course, is a set of questions

with ever-evolving answers.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 10-13-2005 03:53 PM:

Availability = Utility

Hi john, All

Just a couple of clairifications regarding the location

of the tribes

which tenatively, as suggested by the dealer, produced your

rug.

You had stated that

"Early Russian maps and two German