Posted by Stephen Louw on 11-21-2004 01:31 AM:

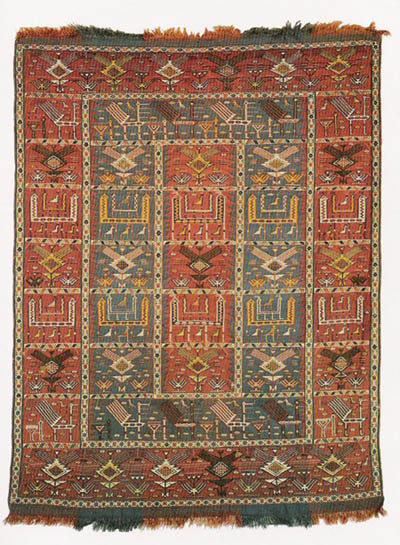

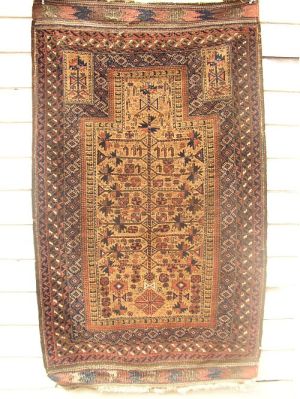

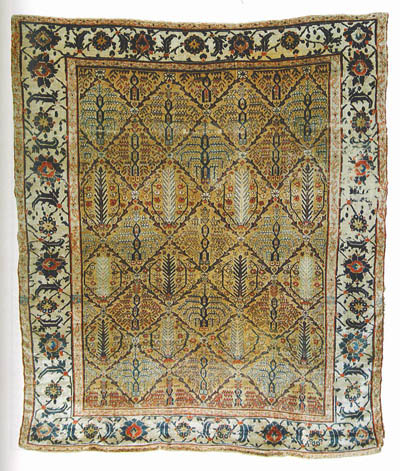

Middle Amu Darya weaving

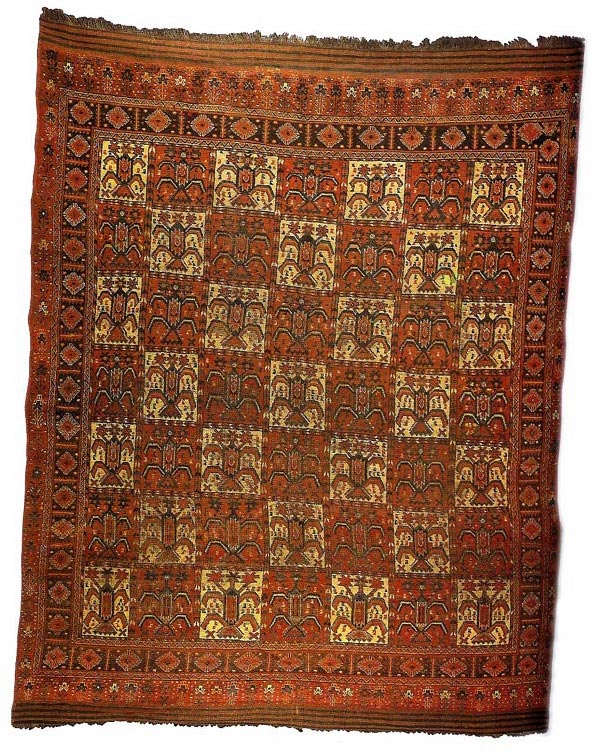

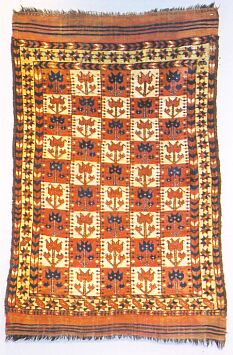

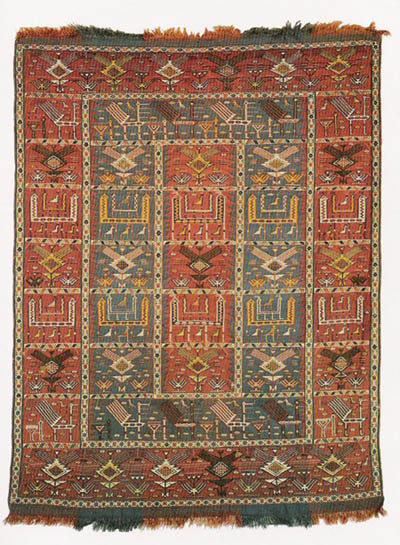

I am trying to focus my collecting instincts on rugs from the middle Amu

Darya region, especially their main and long carpets (kelleh) which, in my view,

offer a fascinating mix of urban and rural influences, incorporating creatively

various Central Asian, Chinese and Persian aesthetic influences. Clearly the

products of fairly established weaving settlements (the size alone suggests

this) and, in all likelihood, woven with an obviously commercial intent,

collectors do not always appreciate these rugs, which are sometimes even –

horror of horrors – catalogued as decoratives!

I like them though, and am

especially pleased to have had the chance to acquire this piece, which, despite

its obvious condition problems, is a reasonable example of the

“compartmentalised tarantula design” (my term). The drawing is freer and more

quirky than the one illustrated in Jordan’s book, and the colours are fabulous.

I am away from my books, and cannot think of other published examples

offhand.

There is some cotton in the pile, asymmetric knots open to the

right. Size: 289 cm x 136 cm (9’6” x 4’5”).

The person from whom I

bought the carpet suggests that the weave is Kirghiz and there are some Saryk

elements in it. Neither of these strikes me as likely, and I am inclined to

attribute it generally to its place of origin, the Amu Darya region, or, for

convenience, the term widely adopted in the market, Beshir.

What do you

think?

Detail:

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Steve Price on 11-21-2004 09:19 AM:

Hi Stephen

In simpler times, not so many years ago, we would have all

agreed that it is Ersari. Today we know enough to be confused.

Whatever

the weaver's home, it has terrific colors.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 11-21-2004 10:35 AM:

Hi Stephen,

You are right, in spite of its condition your rug looks

better than the one in Jordan’s book.

Congratulations,

Filiberto

Posted by Itzhak Mordekhai on 11-21-2004 01:23 PM:

What does it do to your heart.

Hello Stephen,

Since my last thread on Karakalpak or Uzbek, my

long-held conviction has only been strengthened: What is REALLY important about

a rug is what impact it has on your heart, whether it races faster every time

you lay your eyes on it, or not. The question of origin, although academically

challenging, is less significant.

Congratulations for a fantastic carpet.

It's a knockout!

Regards,

Itzhak

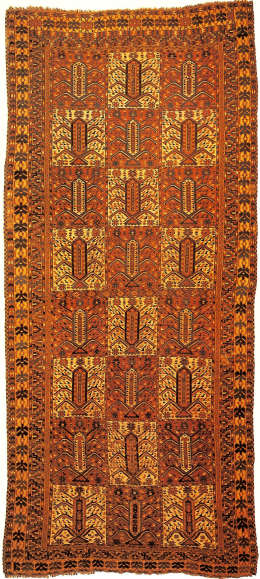

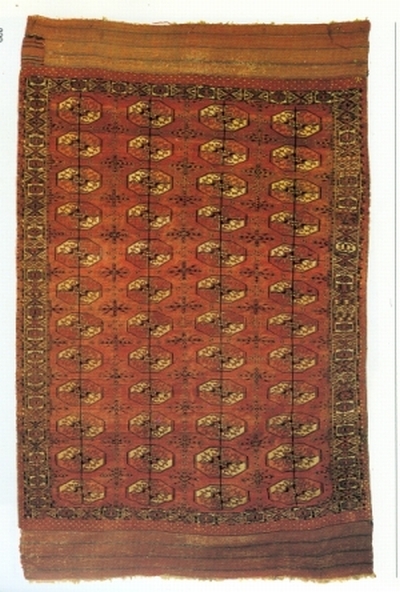

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-21-2004 06:14 PM:

Bugs ?

Hi Stephen,

Nice rug (read that with a slightly jealous tone...)

!!

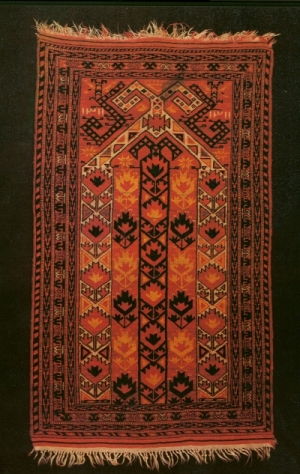

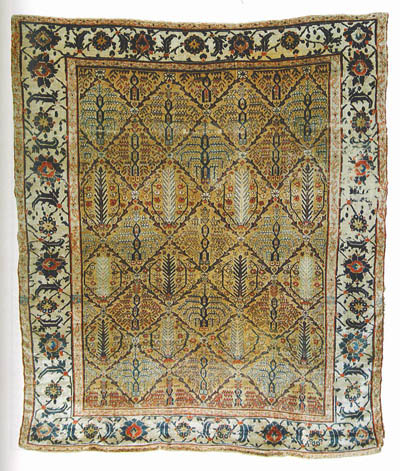

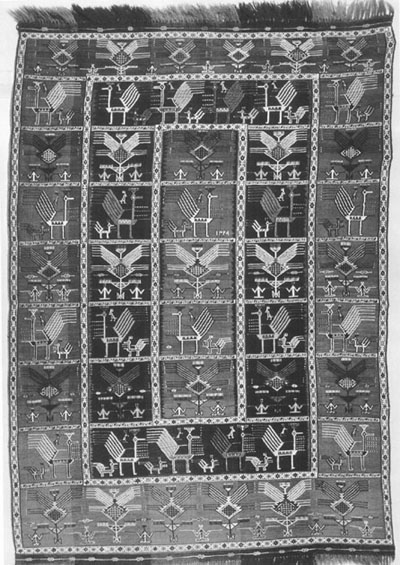

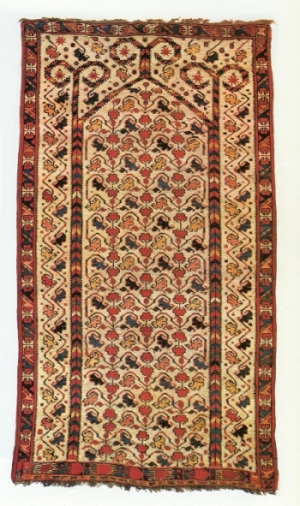

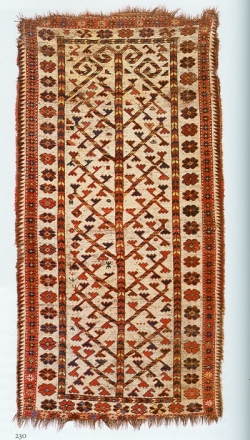

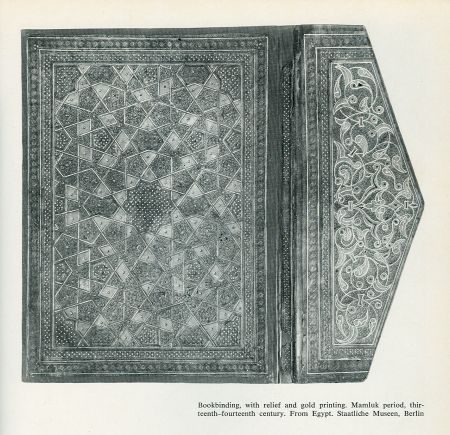

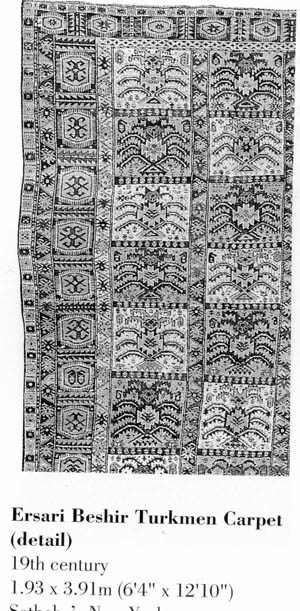

Since you're away from your books, here's the image that Filiberto

mentioned; it's from Jourdan's Turkoman volume:

He mentions that, in the

trade, they're referred to as "Tarantula Beshirs", but states "this description

is unlikely to have anything to do with the meaning or derivation of the

principal motif." and goes on to relate it to a specific design group (unnamed,

oddly) Caucasian rugs.

He notes that the image does not do justice to the

blues in the actual piece; yours certainly has a nice combination. The border on

yours is quite typical for Bokhara workshop goods often marketed as Beshiri

pieces.

Cheers,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Stephen Louw on 11-23-2004 05:57 AM:

Thanks all. Can anyone refer me to any other published examples? I know I

have seen them before, I just cannot remember where.

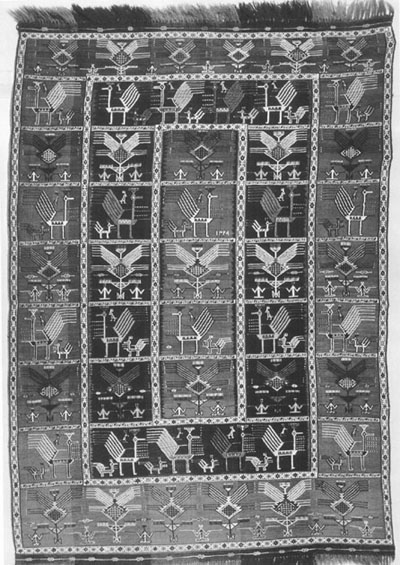

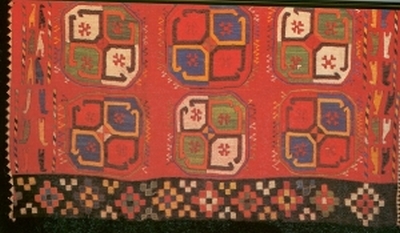

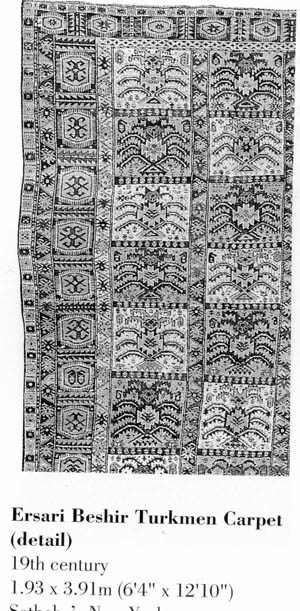

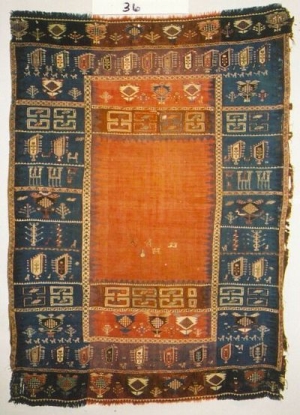

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 11-23-2004 07:15 AM:

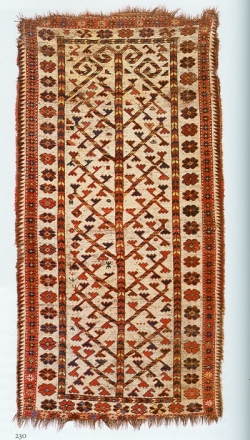

Hi Stephen,

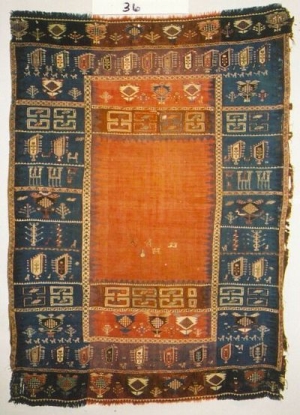

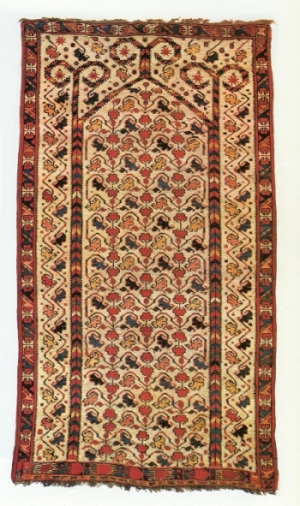

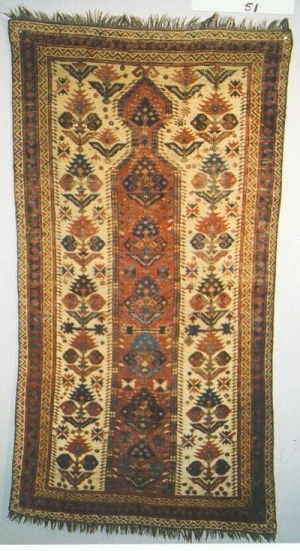

My only copy of Ghereh, (#23) has an article about the

exhibition “Between the Black Desert and the Red – Turkmen Carpets from the

Wiedersperg Collection”.

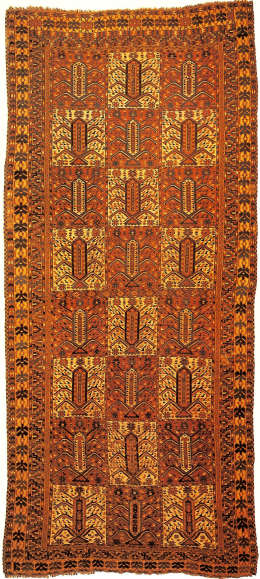

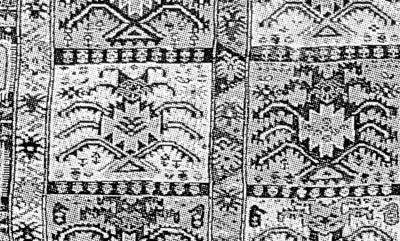

The article has a photo of a rug similar to

yours:

The only information about it is the size: cm 236x127, and I

doubt it is correct.

Best regards,

Filiberto

Posted by R. John Howe on 11-24-2004 08:20 AM:

Hi Stephen -

We talked about your nice piece here off board, so you

already know that I like it too. In addition, I tend to be a "sucker" in general

for compartmented designs (Rich Isaacson here, drolly suggested recently that I

should begin to "think outside the box."  ) I think the graphic impact of the

"tarantula" devices and the alternation of ground color is very

effective.

) I think the graphic impact of the

"tarantula" devices and the alternation of ground color is very

effective.

You started your first post by saying in part:

"I am

trying to focus my collecting instincts on rugs from the middle Amu Darya

region, especially their main and long carpets (kelleh) which, in my view, offer

a fascinating mix of urban and rural influences, incorporating creatively

various Central Asian, Chinese and Persian aesthetic

influences..."

Me:

This is an interesting collecting strategy.

But if I understand correctly, the usage "middle Amu Darya" here means

mostly "we can't tell what it is." Begins to resonate with earlier usages like

"Bukhara" or "Shiraz."

I have been searching for a cluster of stable indicators being used to

signal "middle Amu Darya," but think different folks are using different things.

"Instinct" might be pretty accurate for what seems to be the current state of

affairs.

Do you have a particular cluster of indicators you use to detect

the "middle Amu Darya" pieces you seek?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Stephen Louw on 11-25-2004 08:49 AM:

John -- a good question. Would make an even better Salon!

No, I don't

have a coherent set of indicators. Ordinarily, I would have described the carpet

generically as Beshir, although this, as you know, is a very vague attribution,

as much a product of market lore as anything else. Robert Pinner had a very good

article on the subject in one of the early Hali's, in which he confessed a

similar confusion, and suggested that “Beshir” be used out of convenience (it is

well known and widely used) only.

So my use of the MAD label was meant

simply to imply a certain conceptual confusion and deliberate uncertainty. There

are a certain category of rugs, most of which appear to have been woven in

fairly established workshops, adopting deliberately Persian and Chinese motifs

and using these creatively within a largely Turkmen design vocabulary. Some of

these rugs appear to be far more sophisticated in their construction than

others.

Is that satisfactory? Not really, certainly no less so than

Pinner's use of “Beshir”. Worth thinking about!

Posted by R. John Howe on 11-25-2004 11:08 AM:

Hi Stephen -

As you no doubt know, Pinner and Elena Tsareva worked on

a book on "Beshiri" weavings for several years. Haven't heard anything about it

for quite awhile.

Likely it stalled as Pinner's health

declined.

Maybe Elena will complete and publish it now. I'll ask her if I

get a chance.

Regards,

R. John Howe

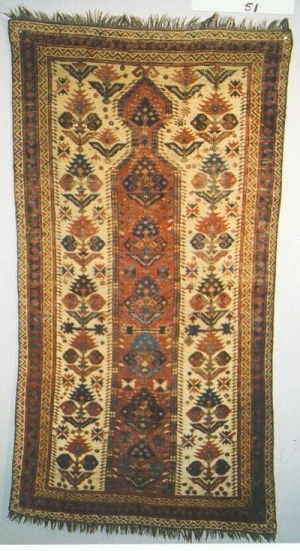

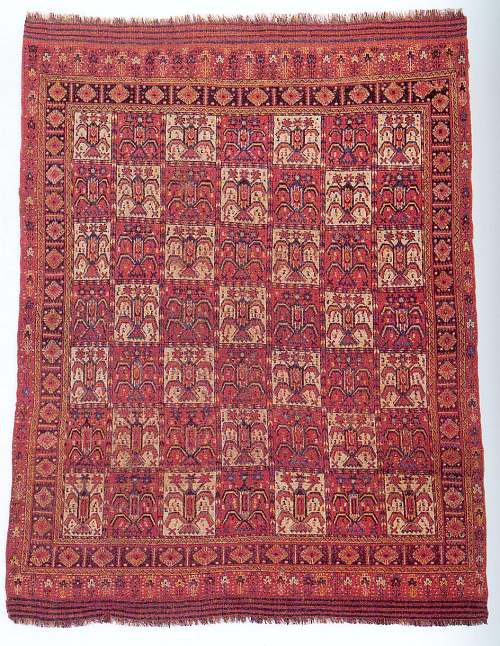

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 11-27-2004 05:20 PM:

On the way to looking up something else, I stumbled across this plate in

Jenny Housego's "Tribal Rugs" (plate 81). Her description is as

follows:

"Pile Rug: Kurds of Khurasan. Northeast Iran. Sylized beetle

forms recall those of the Ersari tribes of Central Asia and Afghanistan. The

colours and the weave, however, are typical of the Kurds of Khurasan who have

adopted several designs along with a wide variety of their own. Characteristic

of this particular group are the gold and tomato red and the zig-zag outer guard

stripes enclosing reciprocal trefoils. Size: 2.96m x

1.58m.

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by Stephen Louw on 11-28-2004 04:39 AM:

Thanks Jerry -- clear scientific evidence, based on an 100% correlation, that

neither Turkmen nor Persian weavers suffered from

arachnophobia!

Seriously, whatever these are or what they are meant to

connotate, one marvels at how universal some symbols and motifs are.

Stephen

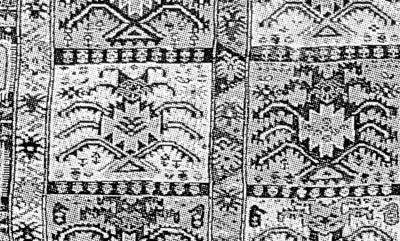

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 11-28-2004 12:52 PM:

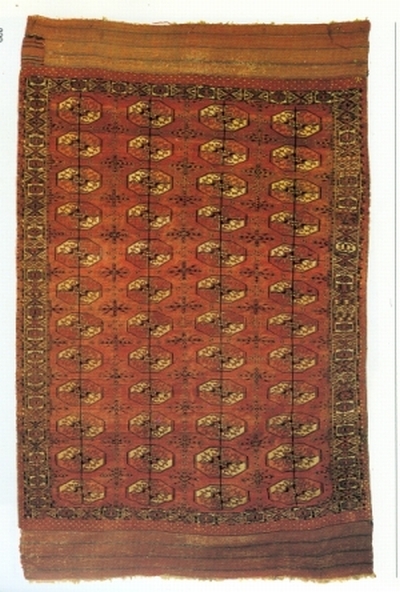

Here is another example of a "tarantula" from the end of a Tekke tentband

fragment shown by the Bells at the Oriental Rugs from Canadian collections II"

in 1998. It certainly looks like some type of bug to me.

.

.

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-28-2004 10:43 PM:

Hi all,

This is a scan of the elem panel from a Salor ensi featured in

Jon Thompson's 'Carpets From The Tents, Cottages, and Workshops of

Asia':

It

shares a couple of the design elements of the "tarantulas": A large central

"stalk" containing a geometric design, Legs (or wings). Although it's a stretch

to say that it resembles a bug, I can't help but wonder if the two designs might

be related at some level.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Horst Nitz on 11-29-2004 01:49 PM:

Hallo All

Whilst the first three rugs discussed in this thread all

seem closely related, plate 81 from the Jenny Housego book does not fit in.

Unlike those other examples her “stylized beetle form” has upright slanting

extremities on either side of the body and does not carry a bunch of flowers

between its jars. To me it seems more closely related to some Caucasian rugs,

i.e. plate 118 from the Karabagh area in Eder, Doris (1990) Orientteppiche, Bd.

1: Kaukasische Teppiche. This is not as unlikely a relationship as it might

seem. The Kurds of Khorassan had settled in the Karabagh region and east of

Ararat for centuries.

This rug displays a colour scheme one could call typical for

some rugs made by the Kurds of Khorassan.

The quite malicious looking

little beastie on the tent band of which Marvin Amstey had send us a picture is

of a quite different ilk altogether. It does not appear stylized at all but

ready to jump at anything getting near

it.

Regards,

Horst

p.s. For granted: In their daily lives

those weavers were much less occupied with heraldic shields and medaillons of

sorts than they were with beasts of the type on the tent band (had to restrain

myself not to call it lousy). Obviously, depicting them on their tent interior

must have mend to charm them away to a certain degree, as is the function of

those house demons in other cultures.

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-29-2004 04:49 PM:

Hi all,

Yes, Horst touches on an interesting point: the creatures

encountered in everyday life by the nomads. Indeed, the design element under

discussion reminds me of what are called "camel spiders" in the Middle East

(actually a tail-less scorpion with HUGE mandibles). Similar species are present

in Afghanistan and throughout the Turkmensahra region.

And one wonders if

the nomads knew each other by the equivalent of their high school "fighting

names", like the (I'm not making this one up...): Battling Sand Crabs of Port

Lavaca (in Texas)...

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 11-29-2004 06:19 PM:

...and the cheerleaders shouted: "Give me a 'C'. Give me an 'R'. Give me an

'A'. Give me a 'B'. Give me an 'S'. Whaddaya' got? Crabs! Yippee!"

Must

have been rousing.

-Jerry-

Posted by Tim Adam on 11-29-2004 11:58 PM:

Except for Marvin's tendband, I think none of these designs represent bugs.

Why would anyone want to stand on a pile of bugs? Doesn't make sense to me. I'd

find it more plausible if these design elements represented some sort of grain.

Then the first rugs presented in this thread would represent grain fields. That

would make sense to me.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Stephen Louw on 11-30-2004 02:01 AM:

Grain fields?

I think we must be careful not to let our imagination's

run away with us here. I used the term "compartamentalised tarantula" design as

a tongue-in-cheek description only. With the exception of the tentband fragment

posted by Marvin, which does appear to be quite literal in its representation of

an animal form, I personally am happy to leave it at that.

__________________

Stephen

Louw

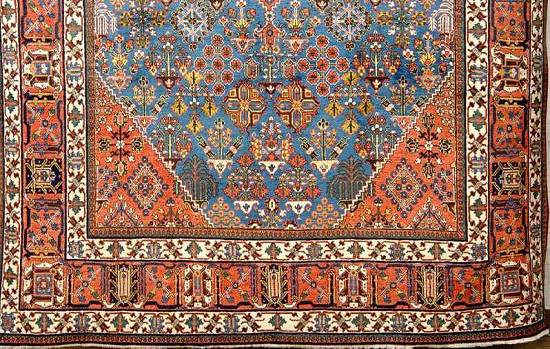

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 11-30-2004 02:58 AM:

Can't see the wheat for the trees.

Stephen,

I suspect you are correct with your opening statement about

these Middle Amu Darya weavings, they offer:

"...a fascinating mix of

urban and rural influences, incorporating creatively various Central Asian,

Chinese and Persian aesthetic influences"

Tim suggests wheat as the

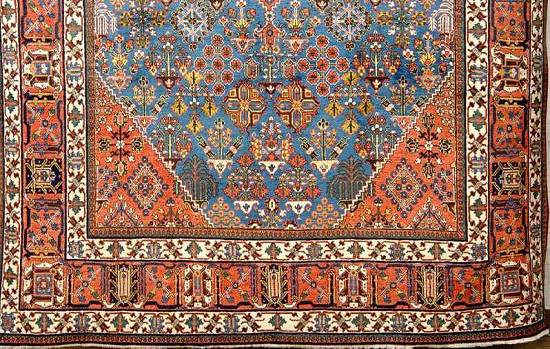

source for the design of your exquisite acquisition. My leaning is towards

trees. Bakhtiyari garden carpet trees as seen in this rug on the Jozan

website:

http://www.jozan.net/billeder/Bakhtiari1/Bakhtiar_BostonGalleries.JPG

In

both outer columns of panels, the second and sixth rows show a design quite

similar to yours. It is a tree with the same type of hexagonal trunk and these

have three white branches coinciding with the branches on your trees.

The

Bakhtiyari branches do not droop as yours do, but the basic design elements are

the same.

And, just as Indian carpets took on Persian designs, these Middle

Amu Darya designs may also have been significantly influenced by classical

Persian designs such as the compartmented garden design.

The colors in

your rug are spectacular. If you run out of room to display it, send it to

me!

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 11-30-2004 08:52 AM:

quote:

Originally posted by Stephen Louw

I think we must be careful not

to let our imagination's run away with us here.

Hi All

I think Stephen's point here is right on the

money and important. These motifs (and others, of course) have origins buried in

the dustbins of time and are probably beyond being knowable. Speculation on what

they represented once upon a time can be fun, but it usually leads to long

diversions that end up going nowhere. This is especially true for Turkmen

motifs, about which there is probably more nonsense written than those of any

other group.

The ones under consideration look sort of like crawling

insects (especially Marvin's), arachnids, fields of plants, trees, Viking ships,

back to back horses or other animals, butterflies, birds, TV antennas,

flowerpots with latchhooks for fastening to a window sill, graveyards, rows of

telegraph poles; the list can go on forever. Without a firm basis for deciding

which, if any, is correct, debating what it is that they most nearly resemble is

unproductive.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Tim Adam on 11-30-2004 10:01 AM:

Hi Steve,

I agree that design interpretations are highly subjective

and can rarely be proven. So there is usually no point to insist on a particular

interpretation. But I think that one can destinguish between the plausible,

unplausible, and the absurd.

For example, the ubiquitous 'crab border' in

Caucasian rugs has nothing to do with crabs at all, as better drawn examples

show. I feel it is worthwhile to point this out.

Tim

Posted by Steve Price on 11-30-2004 10:46 AM:

Hi Tim

You're right about the "crab" border, of course. Like most

motifs with unambiguous identities, it is clearly floral. People seem to hate

that reality - flowers fuel our fantasies so much less effectively than sacred

birds, scary crawling things, etc.

quote:

Originally posted by Tim Adam

...design interpretations are

highly subjective and can rarely be proven. ... But I think that one can

destinguish between the plausible, unplausible, and the absurd.

We can do the triage that you suggest, and eliminate

certain alternatives as implausible or absurd. But the list that remains is

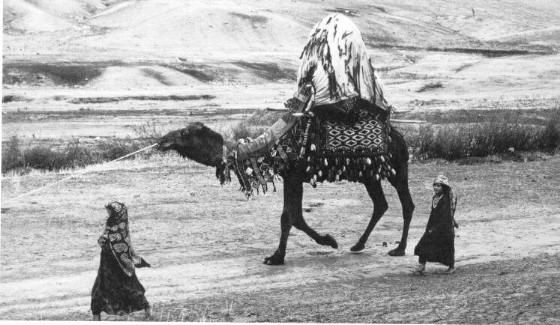

usually still very long and it would be foolish to think that it contains all

the plausible alternatives.

Some even ignore the interpretations that

seem most obvious, preferring to pursue their fantasies. One example that comes

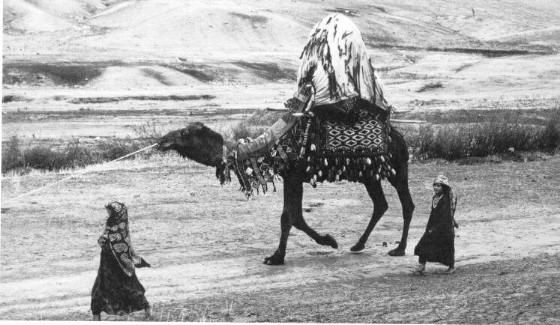

to mind is the so-called kejebe design used by most or all Turkmen groups. One

self-proclaimed expert on Turkmen stuff claims to have been pondering its

meaning for many years. The Turkmen call it "kejebe", which is the tent-like

affair atop the bridal camel in a wedding procession, in which the bride is

enclosed. That's either a good hint or a big red herring.

This doesn't prove that the

design represents a kejebe, but it seems unlikely that anyone will be able to

generate a better evidence-based explanation by pondering the matter.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-30-2004 12:20 PM:

Hi all,

I was serious when I suggested that the design on Stephen's

rug might be a graphic representation of the "tribal nickname" of the weavers

tribe. Bug or not, it's certainly a reasonable suggestion.

Central Asian

tribal names such as Kizl Ayak (red-footed), Firoz Kohi (blue mountain), or Kara

Koyunlu (black sheep) have no possible connection to Apache tribal names like

Jicarilla (little basket) or Chiracauha (great mountain) or Mimbrenos (willow

people). Yet each nomadic culture has derived tribal etymologies from similar

roots. Such "tribe : observed characteristic" associations must

also work their way into pictorial tribal art.

The design is fairly

uncommon among the Turkoman rugs extant today, but it may well be a form of

tribal gul that departs from the typical polygonal designs. It seems a little

odd to me that Turkoman tribes would be weaving odes to corn or grain harvests;

farming wasn't really their strong point. But I agree that it's a

possibility.

The bug on the tent band is obvious; there is a similar,

somewhat less obvious form of bug that is seen on some Baluchi

weavings:

Both bear a strong resemblence to what Persians and Turks call

carpet beetles, and what the Egyptians revered as the scarab beetle. What I find

most interesting about the "band bug" is that it is one of the very few

well done Turkoman animal drawings I've seen.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Steve Price on 11-30-2004 12:50 PM:

Hi Chuck

You wrote, "tribe : observed characteristic"

associations must also work their way into pictorial tribal art. That's

undeniable, but it isn't the same thing as being able to identify the meaning or

basis of those characteristics. Maybe that thing is an insect, maybe it isn't.

Maybe it's related to carpet beetles or scarabs, maybe not. Maybe it represents

something else, maybe it's an abstraction (that is, it may not even be

pictorial). I don't know of any basis on which to make a judgment about what it

is or even whether it is representational.

Just to muddy things,

consider the design on your bagface. There are people who will read the heavy

lines in the lower part of the field as riverboats, others who will see the pale

red lines at the top and bottom of the field as women giving birth, or the pale

red lines and center device as a seated noble or god. The elements projecting

laterally from the center device will be read by some as bows and arrows. None

of these is absurd or implausible, but the list can become so long as to render

the exercise pointless.

The problem is, we have no way of knowing which,

if any, of these reflects the truth as seen by the weaver and her community.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-30-2004 12:58 PM:

Hi Steve,

I'm surprised you didn't notice the Yomud border along the

top edge...

By the way, no thoughtful speculative inquiry is

pointless. Many are fruitless, however.

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Steve Price on 11-30-2004 01:16 PM:

Hi Chuck

You're right- there is a difference between something being

pointless and something being fruitless. I used the wrong word. Fruitless is

better and more accurate.

The border at the top is not only common among

the Yomud, it's also almost universal in Caucasian soumak rugs. It's clearly a

representation of the coat rack at the entrance to the tribal community

bathroom.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 11-30-2004 04:32 PM:

Dear Steve,

Nice interpretations!

Can you send a little of what

you've been toking out here?

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by Tim Adam on 11-30-2004 09:06 PM:

Please correct me if I am wrong. I thought there are two 'types' of Turkmen,

true nomads, and those that were more settled, and pursued some limited farming.

In addition there were Turkmen living in cities, like Bokhara. Those city

dwellers are quite likely to have engaged in

agriculture.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 11-30-2004 10:19 PM:

Hi Tim,

It's my understanding that there have always been some crop

growing settled nomads around the Central Asian oases. And, following the

massive displacements of the Turkmen tribes by the Soviets and the associated

collectivization of farming, even more formely nomadic people settled into at

least a partially agrarian lifestyle.

So it's not inconceivable that

we're looking at the Central Asian equivalent of a Harvest Quilt. It seems like

we're converging on the text of a question for John to ask Elena Tsareva: Has

she seen evidence of agrarian symbolization in Turkoman or other Central Asian

woven goods ?

One would think that there would be less commonality

between designs if these were one-off home woven "harvest" pieces. Having said

that, we certainly haven't seen very many pieces with this

motif.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 12-01-2004 02:40 PM:

Agrarian motifs are well known in "Ersari" weavings. They are probably from

settled folks, and their old examples are in great demand and scarce. I refer to

the "Beshir prayer" rugs with all the hanging pomegranate fruit.

Posted by Louis_Dubreuil on 12-01-2004 02:56 PM:

In the last Hali issue (137/ page 83) there is a Josheghan silk rug, central

Persia, circa 1800 (145X173 cm), private collection, Austria.

The field of this rug shows

a diagonal lattice with alternated palmettes and "shrubs". Those "shrubs" look

like the "tarantula" devices of the Beshir rugs. This phenomenon is quite

current: same motives can appear under "floral" forms or under "animal" forms.

Generally, "animal" forms are encountered among the tribal works while "floral"

forms often correspond to urban and workshop weavings. All the question is to

know what is the original form, animal or floral? Who has copied

who?

Meilleures salutations à tous

Louis Dubreuil

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 12-02-2004 05:24 AM:

Hi Louis,

The general idea is that tribal weavings were influenced by

urban and workshop ones, not the other way

around.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Stephen Louw on 12-02-2004 10:16 AM:

Hi

Even assuming that it is correct to use the term "tribal" to imply

somehow less developed, less settled, less urban -- and that strikes me as

something one would read in an anthropological text written during the British

Raj, and I doubt that any contemporary anthropologists would accept this usage

at all -- I see no reason why the interaction between town and countryside would

not be a reciprocal one. Are less-settled people any less creative and willing

to adapt than more settled people? Perhaps they are sometimes more resistant to

change, but that strikes me as a relative distinction at best, not a

rule.

Stephen

Posted by Steve Price on 12-02-2004 10:36 AM:

Hi Stephen

Unfortunately, the word "tribal" in Rugdom is often used as

a synonym for "nomadic". Even "nomadic" is often an incorrect descriptor of some

of the weaving groups to which it is applied.

We're unlikely to be able

to change this, although it's worthwhile reminding each other of the facts from

time to time.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 12-02-2004 01:17 PM:

Hi Stephen,

Personally, when I use the terms Tribal, or

Cottage, City-Workshop and Court carpets I have in mind Jon

Thompson’s framework (see his book “Carpets From the Tents, Cottages and

Workshops of Asia”) and I assume that most of our participant do the same… No

anthropology involved.

quote:

I see no reason why the interaction between town and countryside would not be

a reciprocal one

With regard to this, the same Jon Thompson wrote a convincing

argument in the above mentioned book, chapter six (Court Carpets), second

paragraph.

I’ll copy it here for the ones that don’t have

it:

Court styles and their influence

The rulers of the

great Islamic courts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were notable for

their patronage of the most outstanding artists of the day. An important element

of their patronage was the maintenance of a design atelier under the immediate

direction of the court. The court artists produced designs in a variety of media

including textiles and carpets, setting the pace for new styles and fashions.

The carpets therefore, together with ceramics, calligraphy, paintings and so on,

form part of the corpus of art produced under the patronage of the dynasty and

are named accordingly. As the ruling houses were Muslim, the carpets are, with

reason, classified as Islamic art. The workshops themselves were sometimes

staffed by craftsmen in the direct employment of the court, but more often they

acted as suppliers of goods of a standard and design specified by the royal

atelier. In this case working for the court did not preclude the makers from

engaging in normal commercial activities; nor did it prevent rival workshops

from turning out similar, less expensive items in the same style. For example, a

whole gradation of quality from the outstanding to the mediocre is seen in

carpets and textiles worked in the Ottoman and Mughal court styles. High fashion

then as now was surrounded by its imitators. More imitators copied the

imitations and so the style worked its way outwards to towns and villages far

from the capital. Women in the rural communities may never have seen the

originals, and had no access to luxurious materials, so they copied the new

style in the medium they were accustomed to. Velvets were translated into

embroidery and knotted pile work (illus. p.2O) ; luxurious carpets with silk

foundations were copied using less costly yarns. Inevitably the designs were

adapted and corrupted but they lived on to be incorporated into the folk

tradition. Here they survive in rustic form centuries after the originals have

passed out of fashion.

James Opie, in his “Tribal rugs” dedicated a

whole chapter to “Urban Influences in Tribal Rugs” producing several examples.

The first is a very telling Quashqa’i workshop rug copy of a mille-fleurs Mogul

rug. (Yes, “Quashqa’i workshop” – so, it’s tribal or not?)

As a see it, I

find highly improbable that a tribal design could have inspired a Court carpet,

although I’m open to evidence.

I think that the influence was like Thompson

describes: from the Court workshop to the City workshop, than to the village and

so on. In the process the design were, more than copied, adapted and then mixed

with tribal elements. It was more a fusion - like in certain music or food -

than a copy.

Now, it has to be seen where the “tribal” ends and the

“cottage/town workshop” starts…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Wendel Swan on 12-02-2004 01:19 PM:

Lesghi star

Dear Steve and all,

The self-professed expert should compare the

kejebe design with this early re-entrant type rug in the Alexander collection,

where I believe he/she will find more correspondence than with any structure

placed on a camel or, as to the “ram’s horns”, any set of horns on any

quadruped. A saph in the T.I.E.M. also bears a close relationship.

At the

moment, I can’t suggest more than that the arch form in the Alexander piece may

derive from Kufic writing or architectural motifs or even some combination

thereof. Similar devices can be found in several Seljuk carpets.

Anyone

wishing to understand the development of Turkmen designs should begin by

examining early Turkish carpets. This will not provide either definitive answers

or a time continuum, but will fill in some of the gaps.

To the notion

that we are seeing spiders, crabs, beetles and insects of one sort or another, I

give a seasonal response: Bah, humbug.

Wendel

Posted by Louis_Dubreuil on 12-02-2004 05:04 PM:

Bonsoir à tous

In Hali 99, page 128, there is a Beshir rug with the

same family design. The design can be read as a family of bugs or other animals

(look at the little bugs in the lattice bands!). But it can be also flowers or

burdocks (the "pitrack" motif of the Anatolian weavers, Mine Erbek's book,

Anatolian Motifs, pages 108 to 111)

I think the floral or

vegetal hypothesis is more serious than the animal hypothesis.

For

example we can look at the Yomud tent band "creature". In the same Hali issue I

have found an enlarged picture of the "bug". It is possible to see the floral

nature of the central part of the motif. The two symmetrical devices on each

side of the central stalk can be read as "fantastic creatures" or dragons

warding the central flower, or more simply vegetal protuberences rendered in

"animal style drawing".

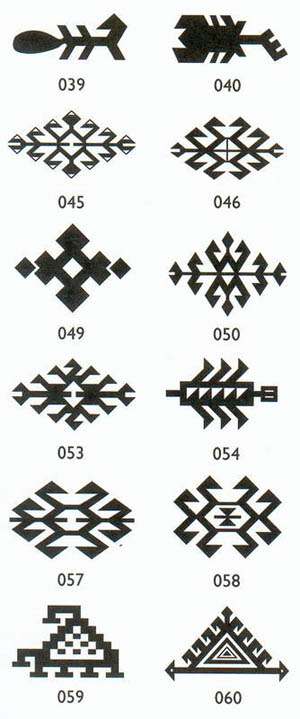

We can see similar stylistic hybridation in some details of my

dragon sumak

Often the "vegetal/floral" or "animal" reading of the motif

depends of the direction of the reading. If you put the Yomut device upside down

it apears to be more animal than floral.

I think it is a conscious

game that weavers play.

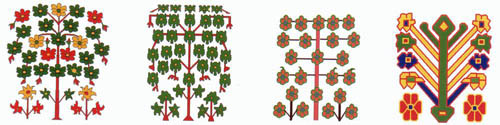

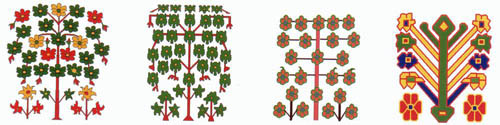

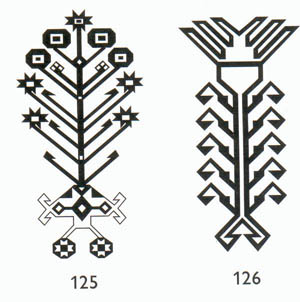

The origin of the "tarantula" design can be the

classical motif "flower in a vase", or "flowering shrub", as we can see in the

schemas of Peter Stone's book, in the Bakhtiari pages

It can be also a derived

form of the "tree of life" as we can see in very stylized forms in Anatolian

weavings (Erbek's book, pages tree of life), motifs from Milas and Midge

areas

The explicit animal motifs exist in weaving vocabulary, but

with less numerous forms (birds, scorpions, quadrupeds, dragons, lions). And

they are generally not symmetrical.

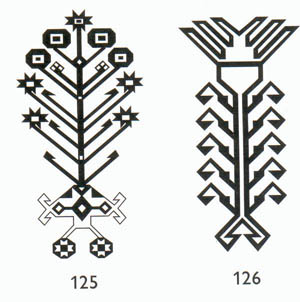

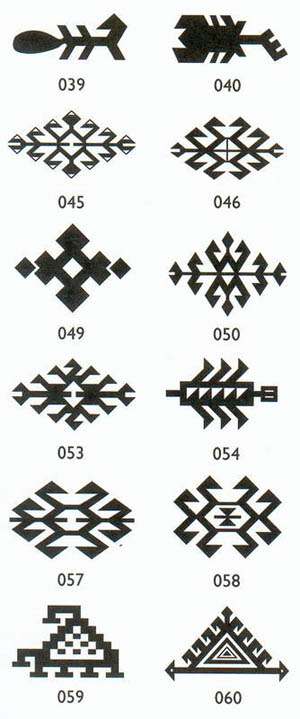

The scorpion is present in Anatolian

weavings, with schematised forms that are generally far from the "tarantula".

Some scorpions are non symmetrical, some are symmetrical with generally two axes

of symmetry. The only example I know that is quite near of "tarantula" with only

one axis of symmetry, is the picture 54 in the following image (from the Erbek's

book, page scorpions).

I think the animal look that floral motifs take when woven by

"tribal" weavers is due to the systematic use of the axial symmetry. Symmetrised

lateral protuberences, even floral, refer immediately to animal forms as they

are read like legs. This fact is amplified when the motif is not symmetric in

the other axis: the shape has a tail and a head (see the Yomud device). This

immediate reading is surely related with a very old part of our brain, as in the

deep past of man little animals with numerous legs were in the same time enemies

(louses, spiders, crab-louses..) or food (ants, bees, crabs and so on) and then

very important for the life of men.

Voilà

Amicales

salutations

Louis Dubreuil

Posted by Steve Price on 12-02-2004 05:32 PM:

Hi Louis

I agree. When representational motifs in central and western

Asian weavings are unambiguous, they are usually floral or, at least, vegetal.

On one point, though, I disagree.

You wrote, Symmetrised

lateral protuberences, even floral, refer immediately to animal forms as they

are read like legs. ... surely related with a very old part of our brain, as in

the deep past of man little animals with numerous legs were in the same time

enemies (louses, spiders, crab-louses..) or food (ants, bees, crabs and so on)

...

Our brain does a lot of "filling in" of images that are presented

visually, not only making insects out of things with symmetric protuberances.

Here are a few simple examples to show how little it takes to make your brain

see a face and attach a meaning to it:

Regards

Steve

Price

Posted by Louis Dubreuil on 12-03-2004 04:58 AM:

Brain

Hello Steve

There is no disagreement between us indeed

. The example you show is the best

example of the power of the brain to read vital signs in highly abstract forms.

Why are we able to read human sentiments in few lines

. The example you show is the best

example of the power of the brain to read vital signs in highly abstract forms.

Why are we able to read human sentiments in few lines  ? this is because it is absolutly

vital to read the faster as possible the intentions on the face of the

individual you have in front of you

? this is because it is absolutly

vital to read the faster as possible the intentions on the face of the

individual you have in front of you  . The corporeal communication is priority holder over the oral

communication. This is true even with primitive animals and overspread in all

mamalian creatures.

. The corporeal communication is priority holder over the oral

communication. This is true even with primitive animals and overspread in all

mamalian creatures.

Amicales salutations

Louis

Posted by Tim Adam on 12-03-2004 06:37 AM:

Hi Louis and Steve,

I wish I'd understand what you two are talking

about, but I think it is an interesting hypothesis that floral forms tend to be

symmetrical while animal forms tend to be asymmetrical. I am sure one can easily

find counter examples, but maybe not that many.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-03-2004 07:51 AM:

Perception=Cognition

Louis,Tim, All

Just a few quick observations folks.

Perception

is a cognitive process, thus learned, as such our interpretation of design

symbols may well differ from those of Turkmen.

If we take a close look

at these Beshier Tarantulas, we will notice that the segmentation of the body

does not reflect that of an arachnid, nor the number of appendages. I have seen

similar motifs on tentbands, if I'm not mistaken, which do resemble wheat. These

same said, or similar, motifs can also be found on Balouch carpets.

While

I share a belief in a vegetal origin of many designs, I think taking this a step

further, and considering the symmetry of the weaving medium itself, with it's

horizontil wefts and verticle warps, moves us closer to an understanding of the

origin of design motifs.

In his Arts and Crafts of Turkestan, Kalter

describes the symbiotic relationship which existed and exists between settled

and nomadic people, and describes the evolution of nomadic culture as being a

reaction to and proceeding from urban culture.

As for symmetry I think we

gotta be careful. I know of an asymmetrical design or two which are clearly

vestigal floral

patterms yet often refered to as scorpions, and while there

are exceptions to every rule, I would exercise some caution.

Dave

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 12-03-2004 10:39 AM:

This discussion seems to be going to the way of another one done here a few

years ago wherein everyone was seeing birds' heads and eagles. Certainly the

examples presented above by Louis from Erbeks's book illustrate the "bird's head

motif we talked about before. Another excercise in futility. Wendel's response

says it all. Have a great weekend.

Posted by Michael_Wendorf on 12-03-2004 06:26 PM:

Do Beetle bags still Bug Wendel

Wendel:

Given your seasonal response above, I have a question ... Do

Beetle bags still bug you?

Can't agree with Marvin's crabby response -

not an exercise in futility, just an exercise.

Carry on, Michael

Posted by Louis Dubreuil on 12-03-2004 07:10 PM:

Hello Marvin

Nobody has yet talk about bird's heads  . The examples draught from the

Erbek's book refer only to flower/vegetal designs (tree of life) and to those

the author has identified as being "scorpions". It is certainly possible to

contest the work of this author, but it seems to me that it is a work mostly

made from field studies or turkish rug culture and from the weavers' names of

motifs.

. The examples draught from the

Erbek's book refer only to flower/vegetal designs (tree of life) and to those

the author has identified as being "scorpions". It is certainly possible to

contest the work of this author, but it seems to me that it is a work mostly

made from field studies or turkish rug culture and from the weavers' names of

motifs.

We all know that there is always a gap between the actual name of a

motif and its original signification. But this work has the merit to exist and

to give us a "complete" survey of the anatolian matter. But also we have to be a

bit distrustful about "complete and definitive" works !

About the

animal drawings on rugs, they are often non symetrical when they have a bit of

realistic rendering : animals are drawn side face, and there is no symetric

animal viewed side face. The only symetric representation side face of animals

is the one of "fantastic " animals like two headed quadrupeds we can see in the

Opie's book on Luri-Bakhtiari weavings.

Animals are drawn in the symetric

manner when seen from above. But this is never the case for realistic birds or

mammalians.

For the scorpions we have two kind of drawings. The non

symetrical is the schematic scorpion viewed side face (a triangle with a tail

fig.59, 60). The symetrical is the beast viewed from above, but in this case

this is generaly a symbolic or an abstract shape (fig 45 to 58) named "scorpion"

by the weaver. Figures 39 and 40 are realistic and symetrical for the body but

not for the tail. This fact is due to the system of drawing on the surface of

the rug : all shapes are flat projected without perspective or 3d taking care .

The body is directly projected on the plane and the tail is projected after a

90° rotation : the scorpion is viewed from above and side face on the same time

Flowers are

generaly symetrical on rugs : one axis (tulips, shrubs or bunches of flowers

viewed side face or from face) or two axis (flowers viewed from above as

rosettes like in the Mina khani design). The only "vegetal / abstract "motif non

symetrical is the boteh.

The other non symetrical drawing of flower motifs

are realistic renderings as "french roses" or more intricated "gul farang" or

non abstract rugs' motifs as in realistic garden carpets.

Amicales

salutations

Louis

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 12-03-2004 08:20 PM:

With birds it depends on the perspective. Here's a Caucasian piece with birds

- in profile and face-forward. Asymmetrical in profile: symmetrical

face-forward.

...much as one would

expect.

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by Louis Dubreuil on 12-04-2004 06:14 AM:

Bonjour Jerry

You are right, "realistic" birds can be symetric when

viewed face forward or even from below, flying. But it remains a relativly rare

disposition. Realistic birds are currently side face drawn and the symetry can

be retored by puting two assymetric birds, face to face, symetricaly on either

side of an axis. We can find again the symetry in "abstract" birds, but this is

not the general rule as even in abstract drawings birds remain assymetric.

I

have forgotten in my review of symetric animals in rugs the tiger rugs of Tibet

which show animal pelts viewed from above with a certain "natural" symetry and a

special kind of old anatolian "animal pelt rugs" that are drawn with the same

principle.

Louis Dubreuil

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-04-2004 10:50 AM:

Birds in the Trees...

Louis and All

I hear what you are saying, but I think you need to take

a closer look at the so designated frontal view of a bird as posted by

Jerry

Silverman. I've seen few birds in which it's wings are attached to a

head which is in turn larger than its body. This looks more a variant of a

floral form such as below.

Dave

Posted by Tim Adam on 12-04-2004 11:17 AM:

David,

I think the wings are attached to the bird's body (in the

frontal view). The head is above the body, and quite

small.

Regards,

Tim

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-04-2004 01:14 PM:

Perspective?

Tim

I don't agree. They , these two figures, seem to me of

differing

structure. I understand the similarities, but the requisit

interpretive gymnastics strike me as proof positive of differing

intent.

Dave

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 12-04-2004 03:04 PM:

Nah. Little head. Big body. Long neck that lifts the little head far above

the body (which can be seen in profile). If the picture I scanned were bigger

I'd have cropped out a single face-forward bird, and this would be more easily

seen.

Turkmen weavers knew what a chicken looked

like.

Cordially,

-Jerry-

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-04-2004 11:22 PM:

A compromise

Tim, Jerry All

I'll admit that this figure could be a full frontal

representation of a fowl, albeit a stylized example of this floral trident with

some zoomorphic attributes.

Aside from the resemblence to this floral

design motif, my primary objection to the interpretation of the motive as a fowl

proceeds from the discrepency between the structure and proportions of the

constituent elements, in comparison to the lateral view of what is obviously a

bird.

Compare the points of attachement of the wings, the proportional

equivalence of the the length of the necks and the orientation of the tails to

the bodies.

If these two design elements we concieved and constructed as

like components, the proportions and details would be more complimentary ,more

similar.

The two elements are floral and fowl, but so stylized as to seem

near the same.

Also, I grew up in the country, my next door neighbor was

a dairy farmer, and we both kept chickens, so I know what chickens look like,

rest assured. There is a resemblence, but it's a stretch.

Dave

Posted by Louis Dubreuil on 12-05-2004 10:48 AM:

Bonjour dave and all fowl lovers

The fowl is roosting on the top of

the flower, I repeat, the fowl is roosting on the top of the

flower.

Meilleures salutations

Louis

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-06-2004 08:56 PM:

Comparison/Contrast

Louis and All

Find below a detail of from a verneh in Thompson's

"Oriental Carpets", pg. 98. No birds here, but the same design and same type of

weaving.

Dave

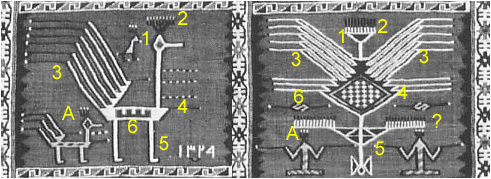

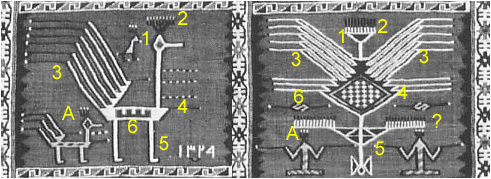

Posted by Wendel Swan on 12-07-2004 10:32 AM:

Hello Jerry and all,

I was initially skeptical that we were seeing

front and side views of a bird (it is a peacock), mainly because it was a

convention that I had never before read about or observed.

Similar

devices can be found on other covers from the Caucasus, including this one

formerly in the Dave Chapman collection and pictured in FTBTS.

I placed two of

the panels side by side without changing scale.

Comparing the frontal

and side views, one finds nearly exact correspondence between the following body

parts of the larger peacock:

1. Head.

2. Comb

3. Tail

4.

Body

5. Legs

6. Wings

There is no obvious explanation for the four

lines above the number 4, but the color and spacing are obviously

representations of the same parts (one dark, three light lines).

In

addition, there is a correspondence of the combs on the smaller peacock (at

A).

There is also another element that remains in question, the lateral

devices on the frontal view shown at the ?. We could speculate that they may

have something to do with the tail(s) of one or two smaller peacocks.

The

frontal views do look remarkably like floral forms, but I?m now convinced that

frontal and side views of the peacock was intended, although it is not unknown

for there to be an expression of duality in some designs.

Perhaps we'll

now notice this same phenomenon in other weavings.

Wendel

Posted by Stephen Louw on 12-08-2004 05:59 PM:

Dear Filiberto

Thanks for the earlier reference to the example in the

Wiedersperg Collection. You noted that you thought the size given in the Ghereh

article (2.36m x 1.27m) was incorrect.

In the catalogue of the

collection edited by Pinner and Eiland, the size is given as 3.61m x 2.01 cm

(142" x 79"), with a knot count of 7(h)x9(v) or 63 per sq. in. (Mine is roughly

8(h) x 11(v).)

There is an almost identical example of this version of

the "compartmental tarantula" design in the Wher collection. This is also

squarer in format, with the much rarer two-legged

spider/scorpion/Martian/flower/germ of wheat; as opposed to the three-stemmed

version in my and the Jourdan examples.

The size of this example is

3.72cm x 2.9cm. It is dated to ca.1800, although I can think of no basis for

that date.

Significantly, this carpet was published as part of an article

in honour of the late Lesley Pinner. We have all recently been saddened by the

loss of Robert Pinner.

__________________

Stephen

Louw

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 12-09-2004 05:10 AM:

Hi Stephen,

Compare the two images… Colors apart (different

typographic rendition) that is the same rug! The slight difference in size can

be easily explained with the irregularity of the rug.

Either there was a

mistake in GHEREH or the rug changed collection.

Regards,

Filberto

Posted by Fred_Mushkat on 12-09-2004 10:34 AM:

Hello all,

For the sake of completeness, here is a photo of a Fars

area band with a fowl roosting on a flower.

Regards,

Fred

Mushkat

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-14-2004 11:25 PM:

Still another Version

All

Another version of this verneh with the floral/fowl motif, from

here on the Turkotek archive.

Guiling, isn't

it.

Dave

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-16-2004 12:26 AM:

Hallo All

Picture 1 shows what can be taken as an animal

form.

Picture 2 shows what else it can be or what it is if one

changes the context.

The vexatious nature of this and many other drawings – let

alone technical aspects for the time being – appears to reflect the tension

field between Islamic picture prohibition and what could be called icons or

images owed to traditional themes and believes, superstitions amongst them. This

may not be the very best example as pictures are taken from an early 20th

century workshop carpet (Meimeh) but it may convey the idea. Context is

all-important when it comes to interpretation and may draw from sources in

anthropology, regional history, Islam, history of arts etc. I can see no short

cut.

Regards,

Horst

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-16-2004 08:48 PM:

Bukhara and Middle Amu Daria

Stephen and All

Find below a color representation of Kush Beggi,

Interior Minister of Bukhara as depicted in Thompson's "Turkmen" on pg. 183,

seated upon one of these palace size Bukhara or Beshir rugs.

There is a

downloadable Tiff scan of this photo which reveals incredible detail on the

Library of Congress website search page. Just type Kush beggi into the search

engine here

For balance, let's throw in a photo of the Emir as well.

In his

introduction to carpets of Bukhara, Thompson, in the chapter of the same name

states that

"For a long time, carpets made in the former Emirate of

Bukhara, which includes the middle reaches of the Amu Daria River Valley, have

been attributed to the Ersari, the largest Turkoman tribe in the area. But the

Ersari produced only a part of the output of the region."

Much is made

of the relationships between these more cosmopolitan weavings and designs found

in jewelry and other decorative arts, such as those demonstrated by this apex of

the scabbard sported by Kush Beggi as above,

and this Beshir

carpet.

In "Turkoman", Jourdan states, in a describing plate 233 on pg. 260

that

"Robert Pinner, discussing a rare carpet in the Museum of Islamic

art, Berlin, noted that there was a rare group of Saryk examples with either the

gulli gul or temirjen gul used as a main motif, but that these were found more

often on Ersari carpets. Considering both the ethnographic relationships of

these two tribes and their common use of such motifs, Pinner concluded that such

guls were used on carpets from the middle Amu-Darya region and were used there

both by the Ersari and the Saryk during the early 19th century before the latter

migrated westward to Merv. Compared to other symmetrically knotted carpets with

this gul, the presenst (Ersari) example differs only in the motif at the center

of each gul and in the use of the minor gul seen here.".

Could commercial

forces have exerted their influences upon Turkmen carpet designs even at these

early dates, in trade centers as Bukhara, resulting in such hybrids as this

Ersari carpet with Tekke guls and Yomud borders, plate 239 of Jourdan's

"Turkoman" and described as

"Although looking very much like Tekke work,

the octagonal form of the Tekke main guls would not normally be found on a Tekke

carpet of this age. The design in the white ground main border is interesting

and no close analogies can be found on any of the Tekke main carpets."

?

Also, could same said forces account for other hybrids, such as

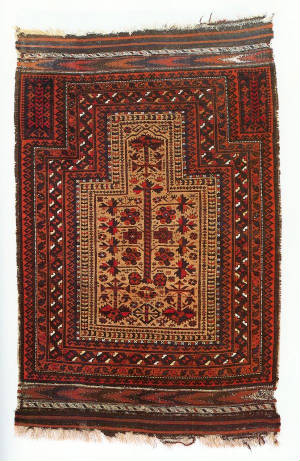

this Ersari/ Balouch prayer rug, possibly modeled after those Beshir/Bokhara

prayer rugs which were made in such numbers?

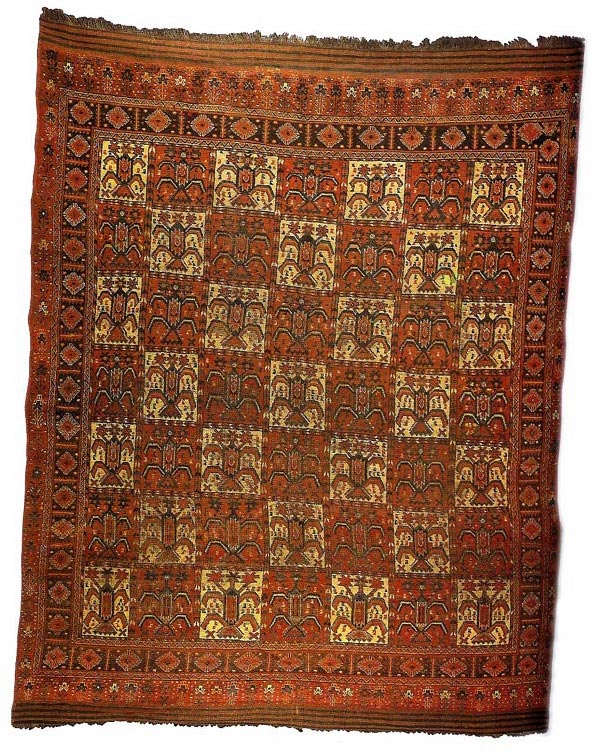

And last,

this compartmentalized Beshir from the Turkotek archive, which is likely based

upon the same model as your so called "Tarantula Beshir" and described by Pinner

in "Between Black Desert and Red" as likely proceeding from Bakhtiari

rugs.

Dave

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-20-2004 06:21 PM:

Hallo David

You are rising very interesting questions. Unfortunately,

I have neither expert knowledge nor time to enter a in-depth discussion now. I

would like to pass two observation however. First, the motive between the

cruciforms on the Emir's sheath reminds me very much of motives that have

travelled as far west as the Balkans and occurs frequently on Shasevan weavings,

a göl-like hooked medaillon form between rams horns; second, to my knowledge the

Temirdjin göl is shared between the Ersari and the Saryk, but white quadrants

with very few exceptions appear to be distinct characteristics of Saryk

work.

Regards,

Horst

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-20-2004 06:33 PM:

Hi David,

again and referring to the last image that has just build

up. Are you suggesting, the motive has travelled east to west from Bakthiari

pastures in western Iran? I do remember Siawosch Azadi having suggested that the

Baluri (Baluch) may be related to the Bakthiari, both using or having used the

symmetrical knot. I am not sure whether this is a widely accepted

view.

Regrads,

Horst

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-20-2004 06:36 PM:

Oh blast,

... has travelled west to east from Bakthiari pastures of

course ... I think I better shut up for the time

being.

Best,

Horst

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-21-2004 07:16 AM:

Two From Thompson

Horst and All

Find below two high end Salor trappings from Thompson's

Oriental carpets. Notice the similarity between the minor guls of both pieces to

the minor gul of the Temirjen gul Ersari above.

As for the Bakhtiari

connection, it appears that the people of the Amu Darya were familiar with their

products and made use of the panel format.

As for the Temirjen gul, it

seems that it's use in Saryk weaving is extremely rare, and most all temirjen

carpets are Ersari. White quadrants are more indicative of an earlier period of

Ersari weaving when lighter colors in general were used, as opposed to

indicating a Saryk origin, IMHO.

I still don't think your Ersari is a

Saryk

Dave

P.S. Find here detailed images of the

Ersari

and both Salor minor guls.

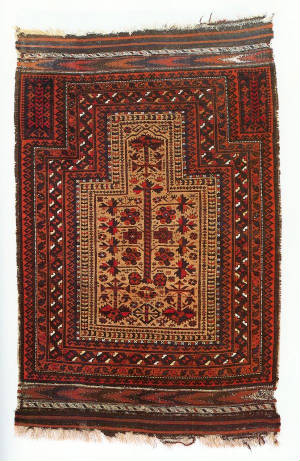

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-25-2004 09:01 PM:

Comparison and Analog

Horst and All

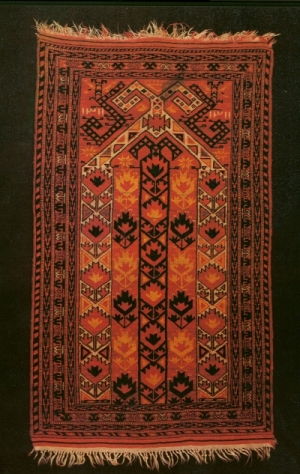

Is it possible that this Beshir prayer rug, which was

made in such large numbers, and seems to have inspired a sea of imitators, is

the Sine quo non of Turkmen and Balouch prayer carpet designs in the Tree of

life format?

In "Between Black Desert and Red", Robert Pinner states

that

"Whatever the actual kinship among these (Ersari) groups, their

lives are similar, particularly as almost all live within the Amu Darya basin or

nearby waterways that drain mountains to the west", and "There are still tent

dwellers among the Ersari group,

but most are sedentary, and the trappings of

nomadic life may consequently form a relatively smaller part of the total woven

woven output". He continues with

"Carpets of the Ersari group are

substantially more variable in size, with some pieces- apparently among the

oldest surviving Tuirkmen rugs- far larger than the Tekke main carpet and

clearly made for an urban enviornment".

"As the areas where these were

woven lay mostly within the Emirate of Bukhara, ande some in the Emirates of

Kokand and Khiva, it is likely that the weavers enjoyed the patronage of

town-dwellers for at least several centuries and to a greater extent than did

the Tekke, Salor, and Saryk. Even now the remnants of the early, traded rugs

that we know as Beshir may be found occasionally in Bukhara, and with the

arrival of the Trans Caspian Railway, a lively trade in these pieces

developed."

Might this sedentary lifestyle account for the large sizes

attained by these Ersari Chuvals, such as the one below?

I have found some

paralles between the drawing of some design elements demonstrated by this

chuval, and an interesting Balouch group prayer rug from the Weidersperg

collection as depicted in "Between black Desert, Etc.".

Pinner notes,

"The

prayer rug is of no specifically identifiable group, although it is considered a

Baluchi type. It is interesting in that it shows three mihrab-like elements

across the top that are strongly suggestive of those found on many Beshir-type

prayer rugs."

Compare the border pattern on the left of this Ersari

chuval

to these filler devices found within the Kochak depicted

below

Also, compare these chemche- like elements from the Ersari

and

Balouch respectively.

Consider the

following Beshir Ersari prayer rug as depicted on pg. 298 in Uwe Jourdan's

"Turkoman" and accompanied by the following caption

"Robert Pinner wrote

that this piece might almost be taken for"it's famous relative from the Dudin

Collection in Leningrad which has been dated by Tzareva to "not later than

the beginning of the 19th century."

Jourdan concludes by stating that

"Because of it's rarity, it's value is almost impossible to estimate".

It

should be noted that the Dudin piece was purchased 1901 in Bukhara and described

at the time as Kizil Ayak.

Another

incarnation from Jourdan's" Turkoman".

In these

Beshir versions we find the disarticulated artifact of a Herati design converted

into a flower, undergoing the metamorphosis into a floral motive which will find

expression in unnumbered Balouch prayer rugs?

Some examples as of

above.

Dave

In the above mentioned link to the Dudin Collection,

Moshkova notes that

"The typical artistic particularity of the Beshir

rug is the absence of a common color for both ground and pattern in contrast to

all turkomen rugs."

Is it possible that the origin of the camel ground,

so often seen in the Balouch prayer rugs,is an imitation of this Beshir

aesthetic?

Or could this lighter ground be reflective of an earlier period,

when the white ground was associated with marriage and yurt culture?

Why so

many white ground Kapunuk?

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-27-2004 05:58 PM:

Hi David

Sorry, to let you down. Your questions are very specific and

half way through with them I start thinking I am not on save grounds on the

subject.

Thanks for enquiring about my Ersari-Saryk. It serves me well

and I am having fun with it. It is top layer in my sitting-room and cushions my

back when the children demonstrate on me what they have learned at their Judo

class.

Best wishes,

Horst

Posted by Jerry Silverman on 12-29-2004 04:49 AM:

All right, David, I just noticed.

Where did you find that picture of

me (see "Emir" above) in my Halloween costume?

Granted, I've lost quite

a bit of weight since that picture was taken - but I won first prize at the

costume contest at Butch McGuire's: $100 and the acclaim of the

multitudes.

-Jerry-

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-29-2004 07:36 PM:

To protect the guilty...

Jerry

Any resemblance to anyone, real or fictitious, is entirely

coincidental. And I refuse to reveal my sources

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 12-31-2004 04:52 PM:

Beshir = besh shahr or "five villages"?

Stephen and All

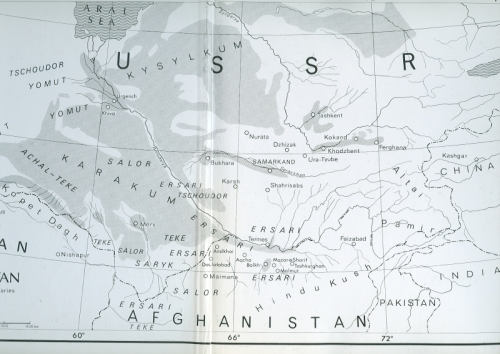

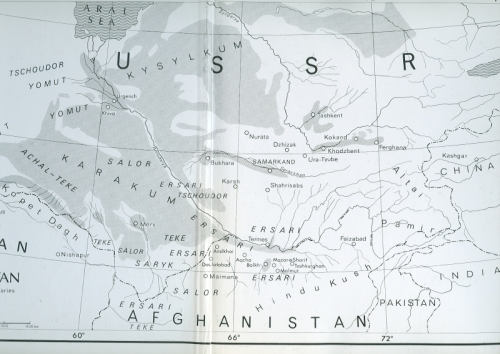

Find below a map of Turkmenistan and surrounding areas

from the end papers of Johannes Kalter's "The Arts and Crafts of

Turkestan".

Notice the proximity of the middle Amudarya to both Merv

and Bokhara. Looks to be the heart of Turkmen territory.

Find

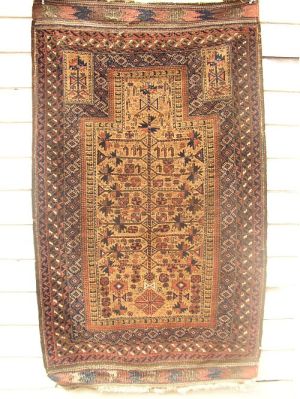

below an Ersari Prayer rug from the Eiland's"Oriental Carpets"

followed

by a Beshir prayer rug, dated to 1893, from Khalter's'Arts and

Crafts,Etc.".

Given the choice, I would have supposed designation the

other way around, Eiland's Ersari to be a Beshir and the Beshir more to the

point as to what I expect in an Ersari weaving.

In "Oriental

Carpets", the Eiland's state

"Rugs with the Beshir or Beshiri label

are among the puzzles, as a number of sources indicate that these pieces are

named for a town (besh and shahr, or "five villages") on the Amu Darya. With

several neighboring towns, this as alleged to have been a nineteenth

century-century production center for a type of rug often inspired by Persian

designs and woven mainly for external markets. Although the authors have not

visited Beshir they have confirmed that rugs of this general type are still

woven in Uzbekistan and are attributed by Uzbeki dealers to the vacinity of

Beshir."

Find below a plate from Khalter's "Arts and Crafts of

Turkestan" depicting both an Uzbek (top) and an Ersari Chuval.

Interesting

that this "bow tie" device in the border of the Uzbek bag is the same at that

found in this Early Beshir from a previous post,

and also in

the main border of this chevron shaped Uzbek "Saye Gosha" trapping. Follow this

Link

to a previous Turkotek discussion of Turkestan material culture.

Here

is what Kalter has to say about the Uzbeks

"The ancestors of the

Uzbeks, like those of the Turkmen, invaded turkestan as armed nomads. The name

of this people, speaking an east Turkic dialect, possibly goes back to one of

the leaders of the Golden Horde of the Mongols, Uzbek Khan (1312-13 -1340). The

prorocess of the formation of the Uzbek people was extremely complex, again like

that of the Turkmen. It was brought about in the 15 th century when Turkic,

Mongol and old-established Iranian groups fused during the decay of the Golden

Horde. In the 16th century, part of the Uzbeks conquered the most important

Turkestan towns and established themselves there, forming the leading class with

considerable contingents of urban merchants and- to a lesser extent-

artisans.Others setteled down as farmers in the the villages of the oasis. In

Russian Turkestan, the Uzbeks had abandoned the nomadic way of life almost

completely by the 19th century, but small nomad Uzbek groups did exist in North

Afghanistan untill very recently."

Of the Tadzhiks, Khalter

states

"In the early middle ages, the word "tazi" was the Iranian term

for Arabs, that is to say Muslims. It was then used by the Turkic uinvaders who

had not yet been converted to Islam to denote those -mainly Iranian- groups

living in Turkestan who had been islamized at a very early period. Today the

name "Tadzhik" is a collective term which includes all those population groups

in Turkestan and Afghanistan that speak a West Iranian dialect closely related

to modern Persian."

and then collectively,

"Since the 16th

century, the urban civilizations of Turkestan have been supported chiefly by the

Uzbeks and Tadzhiks together. The civilization of the cities emerged from a

combination of Iranian and Turkic cultural elements which were molded according

to Islamic conceptions; as has already been mentioned, decisive impulses were

given during the Timurid period. Ideas were also recieved from Persians,

Afghans, Indians, Chinese and others who were living in Turkestan towns as

merchants, and by means of the trade effected with their countries of origin

which at times was very busy."

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-05-2005 07:15 AM:

More Bow Ties

Stephen and All

I found another bow tie element in this border as seen

below in the close up image,

As taken from this

Salor Trapping from Thompson's "Oriental Carpets".

Is the Salor motive an

imitation of the Uzbek motive, is the relationship of the reverse,or could they

both represent a common design motive found in other media, such as in the

embroidered Saye Gosha trapping above?

Find below a pair of earrings

from plate 117 of Kalter's "Arts and Crafts of Turkestan".

Of this

artifact Kalter states

"Earrings composed of three spheroids, like ours

from the Ferghana valley, have been shown to go back to the jewlery of ancient

South Arabia and pre-islamic Iran and had spread throught the islamic world even

in the age of the first caliphs".

Could these be the proverbial

pomegranat?

For further ramblings on the subject of design migration,

follow this Link to a previous salon discussion on

Turkotek.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-05-2005 05:35 PM:

From Saudi to Amu darya?

Find below the image of a Saudi Arabian Bedouin weaving sporting the bow tie

device as seen on the Uzbek, Salor, Ersari, etc. weavings as above, in the event

you haven't read far enough down my excruciating salon, as found at the link

above, to have seen it.

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-06-2005 09:07 PM:

Comparison and Analog II

All

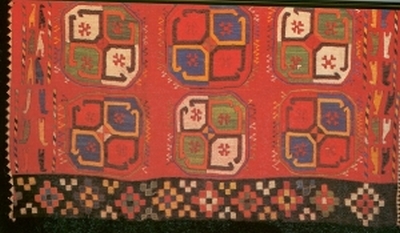

Find below an Uzbek kelim bag with face in soumak

technique.

Notice the scale of the rosettes in the border, the dark

fringes reminescent of salor fringe, and this pale green color which seems to

appear often in both Turkmen and Balouch rugs, and also seems to represent some

technique or style of decor in which the single pale color, in contrast to the

balance, is found among more saturated tones.

In the Salor bagface

fragment from "Pacific Collections" found below we see the corresponding Memling

gul and a similar use of color albeit red instead of green.

Also, this

Thompson piece from above.

In what artistic heritage do

we see the earliest appearence of this Memling gul?

Find below

another example of this above mentioned contrasting technique, this time of the

Ersari. And green too.

Could this

variation in the field, almost as abrash but seeming intentional, be a further

example of this style?

Dave

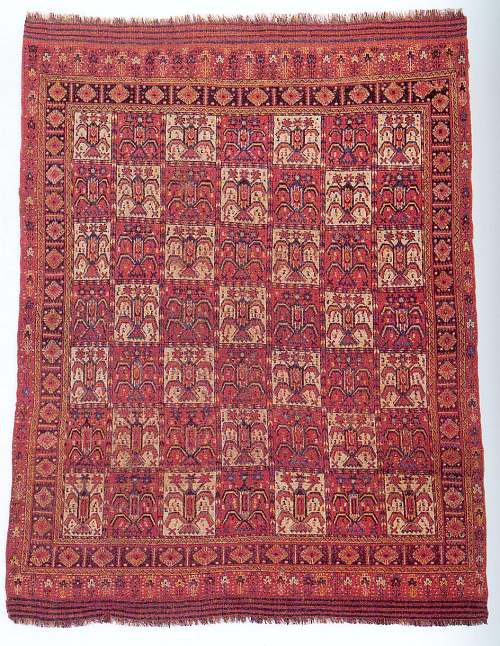

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-10-2005 07:47 AM:

Comparison and Analog III

Stephen and All

Find below a wool embroidered kelim of the lakai Uzbek

from Kalter, 150x342 cm..

Notice how the

drawing of this end border parallels the Chamtos border at the bottom of this

"Pacific Collections" Salor fragment(as also demonstrated by two of the three

other Salor trappings found in this thread),

as do the "S"

border and memling gul like decor of the following Lakai Uzbek embroidered tent

bag from Kalter, 52x118 cm..

If I am not mistaken,

this next band, the stepped triangle adjacent to the "S" border, is also found

in much Turkish weaving.

Kalter states

"Culturally- with

regard to the development of architecture,poetry, the arts of the book and

painting, and also the so-called decorative arts- the importance of the timurid

period cannot be overestimated. Forms and ornaments which appeared in their

characteristic shape for the first time in the Timurid period have dominated the

traditions of arts and crafts untill well into our century."

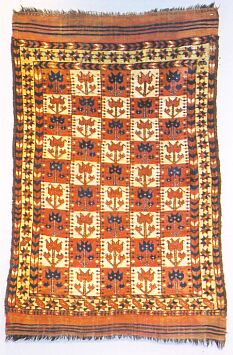

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-10-2005 08:11 AM:

Into the Mix

Stephen and All

Interesting, this tent or bedding bag of the last post

reminds more of more western traditions than Turkmen. Some other groups have

exerted their influence upon Turkestan, as Kalter states

"If today

the Arabs are only to be found in one of the smaller settelments on the Amu

Darya as compact groups, it may nevertheless be assumed that they,too,exerted a

certain influence on Turkestan's material culture. This also appliesto the great

nomad peoples of the Kazakhs and Kirghiz who must however be excluded from this

publication since their possessions are not represented in our

collections."

Notice the white ground of the following Kirghiz

weaving, and it's simularity to the Kazak.

This Kirghiz

piece (below) seems of the Ikat design variety, and notice the "dice" flower

border seen so often in Turkmen weaving. Are those lappets at either end? On

Gerard Paquin's OttomanTextile Designs in Turkish Rugs we read

The

choice of lappets as a type of end border in defining the form of Ottoman silk

yastiks and their wool descendants evolves naturally from the artistic heritage

embraced by the Ottomans. Timurid and Jalayrid miniature painting depict yastiks

in use, some of which have forms analogous to the end lappets of Ottoman yastiks

(figure 38). In those same paintings we see shapes in rows like lappets used

generally as dividers or borders in a variety of architectural uses. Examples of

the use of rows of lappet shapes to demarcate a space can be seen on tops of

walls (figure 37), as decorative friezes such as on the socle or edge of raised

platforms for sitting (figure 38), and elsewhere.[23]

Eureka! Could

this be the model for The "Tarantula Beshir"? notice the similarity of the

rosettes in the compartments of this Kirghiz

to those in the

"Tarantula Beshir" border.

Dave

Posted by Stephen Louw on 01-10-2005 09:15 AM:

Dave --

Very interesting detective work indeed. Thanks for all the

effort.

Regards

Stephen

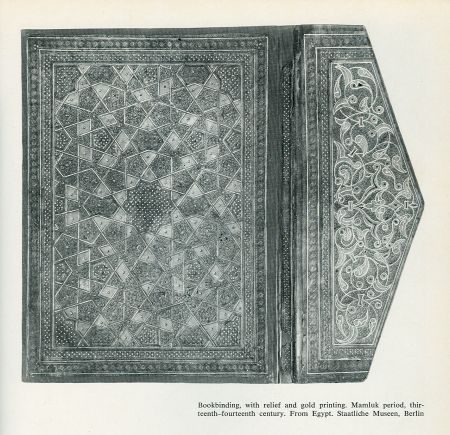

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-11-2005 06:23 PM:

Temirjin Gul?

Stephen and All

Thanks, but the pleasure is mine. This type of

computer research just seems to sear the details into memory. Might come in

handy some day, but with two little ones, at present I am somewhat financially

embarrased.

Find

below some photos of a Timurid (copper/brass?) vessel, not likely period, but

just as with rugs some of these designs never seem to change. Was sold to me as

antique, and does seem to have some age, but I really don't know. Perhaps some

of our readers might be better aquainted?

This photo is of the

underside, showing the concentric rings and the seam where the two pieces, top

and base were joined.

Here we have a view from the front,and about 12 inches

across. Detailed, but I don't know enough to rate. I didn't pay much, so am

satisfied with what I got.

Could this be the octagon

(5cm./ 2 in.), based upon the large scale octagon patterns of the earlier Arab

period of Islamic history( follow this Link and

this Link to a discussion of this topic) which seems to have

launched a thousand imitations, from Mamluk

to Holbein to Kazhak

and Turkmen (temirjen gols?)? Notice the Timurid cap at the

junction of the islamis. This same type of scrolling is found on book covers of

the Mamluk period,

yet no

curvilinear carpet designs?

Dave

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 01-14-2005 11:47 AM:

Mention of Prayer rug exports

All

Find below a short passage from Kalter regarding history and

trade in Turkestan

Only in the 9th century did independant Islamic

states emerge in Turkestan, at first still formally dependant on the court of

the (Arab) Caliph. The most important of these states, culturally as well as

economically, was the Samanid Empire (874 - 999). The Samanid's capital was

Bukhara, their most important governor's seat was

Nishapur.

and,

As documented by tens of thousands of Samanid

coins found in Scandanavia, but also a few scattered ones in Central Europe,

Samanid trade, passing via the Volga basin, reached nearly the whole of europe.

The list of export goods made up by the Arab geographer Mukadasi in the 10th

century (Brentjes 1976), is long and impressive. His (incomplete) list

comprises: rugs and prayer rugs from Bukhara and Samarkand, fine cloths

and weavings made from wool, cotton, and silk, soap, makeup, consecration oil,

bows that could only be bent by the strongest men, swords, armour,

stirrups,fittings, saddles,quivers, tents, rasins, sesame, nuts, honey, sheep,

cattle, horses and hawks, iron, sulfer, copper.

They have been

exporting these rugs for a long time.

Find below an example of this

highly regarded Samanid pottery, viewed from the base and bearing the

inscription, in highly stylized letters,"Frugality is a Symptom of Poverty" and

follow the link to discusion of Early Islamic Ceramics

Dave

) I think the graphic impact of the

"tarantula" devices and the alternation of ground color is very

effective.

) I think the graphic impact of the

"tarantula" devices and the alternation of ground color is very

effective.

.

.

? this is because it is absolutly

vital to read the faster as possible the intentions on the face of the

individual you have in front of you

? this is because it is absolutly

vital to read the faster as possible the intentions on the face of the

individual you have in front of you  . The corporeal communication is priority holder over the oral

communication. This is true even with primitive animals and overspread in all

mamalian creatures.

. The corporeal communication is priority holder over the oral

communication. This is true even with primitive animals and overspread in all

mamalian creatures.