Posted by Rick_Paine on 09-25-2002 01:29 PM:

Dyes and Ethnographic Value

By way of introduction--I am an anthropologist/archaeologist and have

been excavating in southeastern Turkey for the last couple of summers. While I

am there, I like to buy kilims and bags. The stuff I buy is mostly Kurdish

because I work and live with Kurds, have a deep affection for them, and think

their textile work is beautiful. I would not describe myself as a

collector--I'm in it for the experience and a lasting link to the Kurds. I know

virtually nothing about textiles (I probably like them because they are so

absent from the archaeological record).

I have been looking at old

TurkoTek salons for a month or so now, and have noted two very interesting

trends in many of your discussions: 1) a powerful desire to both understand,

and possess, 'ethnographic' pieces; and 2) the battle over dyes. I like the

definition of 'ethnographic' as made for one's own use--though it is hardly one

an ethnographer would identify with. I'll stick with it here.

It seems

to me that these two trends conflict. When a weaver chooses dyes for a piece

she plans to use herself (following above definition), she bases her choice on

several factors: local traditions, what is available, what is convenient, cost

(monetary cost or importantly, her time cost), and what she finds appealing (or

interesting). Synthetic dyes are likely to have been, at various times,

convenient, low cost, and appealing/interesting. When they were new, synthetic

dyes offered a variety and intensity of color unseen in natural dyes (other

salons have delved into the Kurds' particular affection for strong, saturated

colors). They also allow weavers to work in very pure, even color (I find it

hard to imaging the absence of abrash wasn't seen as pretty cool, at least for

a while). We should expect weavers to experiment and explore these new colors,

at least until hidden problems (fading) show themselves. The fruits of these

experiments should be of great interest to anyone looking at textiles from an

ethnographic perspective.

To eliminate pieces characterized by synthetic

dyes, either because of their long-term failure to hold color or because

contemporary tastes (either ours or those of contemporary weavers) run against

them, or our image of the 'primitive,' is to ignore a vast variety of

'ethnographic' pieces. One loses a very interesting period of development

(where isolated, sometimes nomadic weavers began to assimilate products from

the outside world). One also loses yet another of the weaving behaviors I see

constantly praised in these salons: the weaver's desire to experiment and

'play' rather than conforming to programmatic constraints so criticized in

textiles made for sale.

Rick Paine

Posted by Steve Price on

09-25-2002 02:02 PM:

Hi Rick,

First, welcome to our forums.

Your points are

very well taken. I think there are several reasons why many of the people who

hang out here are averse to things with synthetic dyes.

One reason is

not that the dyes can fade, but that they have already faded. I have one NW

Persian bagface with a palette of extremely faded synthetic dyes. The back, not

having been exposed to light, has more or less the original colors. I've shown

the piece to 50 to 100 noncollectors to illustrate the fading that happened to

early natural dyes. I've never had anyone think the front (faded) was more

attractive than the back. Maybe they were influenced by my opinion, but I don't

think so. So, since collectors are interested in aesthetics (many will say that

they're interested in nothing except aesthetics), the stuff with synthetics

loses points on this basis.

Another reason is that many collectors

simply prefer to collect antiques, as opposed to things that are not antiques.

Synthetic dyes pretty much eliminate early dates of manufacture. This is an

irrational reason, but collecting isn't a rational activity to begin with, so

collecting antiques isn't much more subject to this criticism than collecting

at all. Personally, I find it comforting to be around things that are older

than I am that don't look too bad. I don't predate synthetic dyes, but I can be

absolutely sure that things made before the introduction of synthetics are much

older than I am.

The rather exuberant orange used in many pieces around

the first quarter of the 20th century seems to many to be out of harmony with

the rest of the usual palette in which it is found. I guess that makes this an

aesthetic issue.

We can add things like snobbery and peer pressure to

the list.

On the bright side: we are rapidly approaching the point where

the "early synthetic period" (synthetics, but before the chrome dyes) will be

more than 100 years in the past. When those rugs become antiques, the

collectors of antiques will see them through different

eyes.

Incidentally, I was in southeastern Turkey for a week or so last

summer, and can easily understand your affection for the region and its

people.

I hope you'll continue to contribute your expertise to our

discussions.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by R. John

Howe on 09-25-2002 03:31 PM:

Mr. Paine -

You touch a chink in the "armour" of our collecting

standards.

Since the aesthetic standards we employ are seemingly largely

learned, they are a social product and manipulated by the current elite. Any

such phenomenon will have inconsistencies in it and points at which the

justifications offered will conflict. Sometimes it will become evident that

such standards cannot really be justified on the basis of the logics offered

for them. It can become irrational and, yes, we do sometimes bar ourselves

unnecessarily from pieces that we ought to consider more seriously, because we

find a few traces of a likely synthetic in them.

There does seem to be

some sense in which "old is better" is true, but there is no doubt that

meritorious weavings are likely made in every age.

Steve says, we value

the old, and that is true, but the presence of synthetics can actually be, and

this is increasing the case, an indicator of fair age. Not of the possiblility

that a given piece might have been made before 1850 but presence of an early

synthetic may let one estimate with fair accuracy that a piece was woven say

between 1875 and 1910.

At a rug club meeting recently I ran into a

person who owns a few rugs but who is actually a "print" collector. I quizzed

him about the standards he uses and especially about whether the presence of

synthetic dyes in a print lowers his interest in it at all. He said not; that

he is actually glad to find one since it functions as an age marker for him. I

asked him if synthetic dyes detracted from a prints aesthetic appeal and again

he said not. And print collectors are not immune to aesthetic judgments about

color.

At The Textile Museum recently some contemporary weavers were ooh

and aahing over some colors they were using that seemed of the "day-glo"

variety to me. Again, these are folks not untuned to aesthetics, including

color, and they looked at me blankly when I described why antique rug

collectors would find the colors they were admiring unsatisfactory.

And

we are inconsistent when we both admire the gentle pastels into which many

natural dyes fade with age and talk condescendingly about the "glare" of a

synthetic and then move to a dye that we think natural and admire its great

saturation and intensity.

So I would advise you to school yourself a

little. There is something to the standards into which we have been socialized.

But then you should buy what you like and what you think you could live with

and look at for a long time, even if you think such pieces have synthetic dyes

in them.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Filiberto

Boncompagni on 09-26-2002 10:50 AM:

Absolutely, Rick.

I have to say, though, that some open-minded,

ethnographically-oriented, narrow-budgeted

collectors do not refrain from buying modern or not-so-old

textiles with synthetic dyes.

collectors do not refrain from buying modern or not-so-old

textiles with synthetic dyes.

Example:

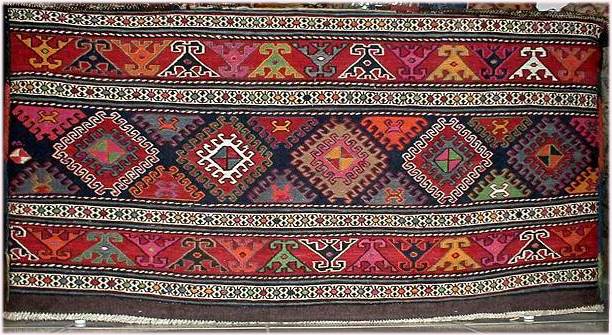

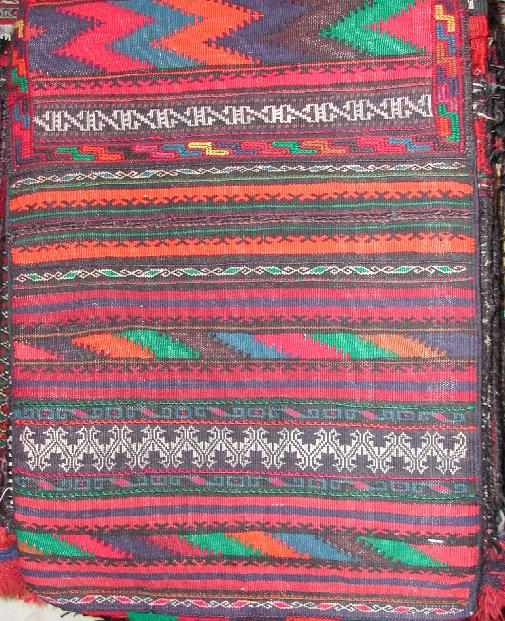

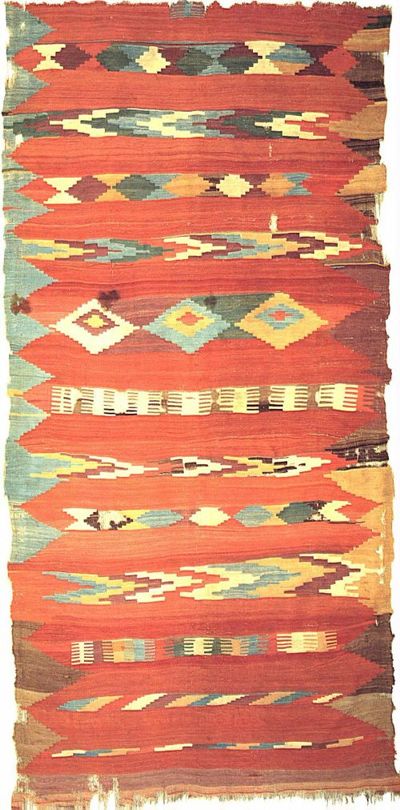

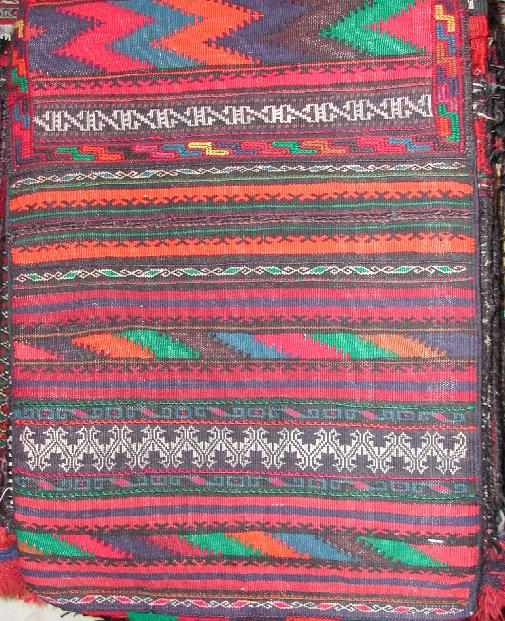

On the left an old tattered mafrash (probably a Shahsavan

from the Moghan region) good natural colors faded, but not terribly, with the

age. There is not a big difference in color between the external and the

internal side - this should be an indicator of natural dyes, I guess.

On the

right a modern mafrash, well done, nice wool, and, ugh you see those pink green

and orange?

(the gray strip under the old mafrash is a Kodak neutral test

card, with a 18% reflectance, that was supposed to help in calibrating the

picture’s colors).

None of them should be a serious

collector’s choice: the first is too ragged, the second for some of its

fluorescent dyes.

I liked the second anyway and I bought it.

It is so

ugly for you?

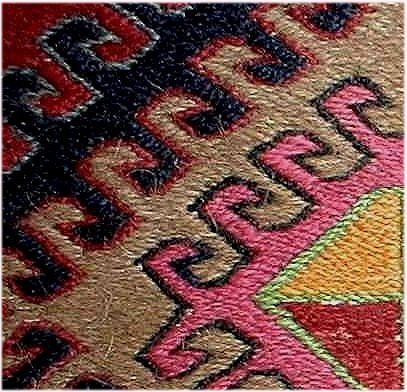

I suspect it is not as new at it seems. It

could be a dowry piece stored in a trunk and never used. The waver made it with

a good care. She used also some camel wool - at least it looks like camel

because it is softer, the fibers are longer and for its color. See

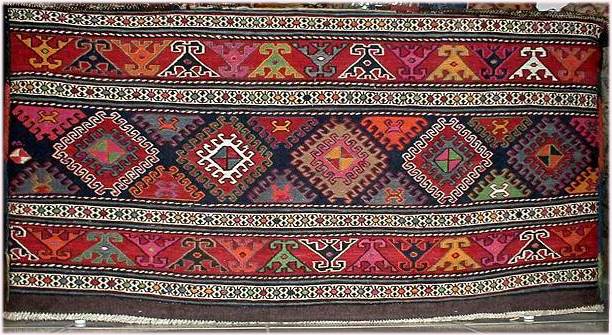

detail:

Then I bought the old one - I liked that too

in spite of its condition.

OK - In a better world I would have only one

mafrash: with the color and the age of the first and the perfect condition of

the second.

My only consolation: they both have - I believe - an

ethnographic value. And I like them both.

What do you

think?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on

09-26-2002 11:13 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

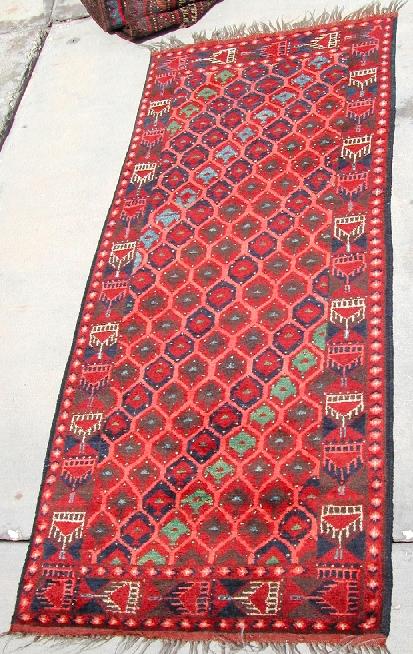

Forgetting about the aesthetics, I think these two

pieces show very nicely what I think of as the "tidying up" that seems to have

happened between the mid-to-late 19th and early-to-mid 20th centuries. The main

band, the two narrower bands, and the "crab"border of the younger one all

clearly have their roots in the tradition of the older one. But in the main

band and the two narrower bands the fluid drawing is replaced by a simpler,

more rectilinear style, and the negative space is much less a part of the

design.

I think having both is a good decision. It really makes each

one more interesting when you can compare them side by

side.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto

Boncompagni on 09-26-2002 11:40 AM:

Hi Steve,

Yes, another point in having them both was the "air of

family" between them. Like the modern mafrash was woven by a granddaughter of

the weaver of the old one. Which, broadly (anthropologically) speaking, is

correct.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Rick_Paine on

09-26-2002 12:52 PM:

First, thank you for the kind welcome and the very interesting

replies.

My post was essentially about the contrast between cultural

interest (ethnographic interest to an ethnographer) and aesthetic interest. I

think both are absolutely wonderful perspectives to approach textiles (or just

about anything else). I did not intend to denigrate either collectors' well

educated (I have been thrilled by the knowledge that comes out in these

salons--I'm learning by the day) senses of textile quality, or an approach to

collecting based on aesthetics. My principal aim was to suggest that many

'ethnographic' pieces have interest that goes beyond pure aesthetics.

Clearly, the two are not mutually exclusive. One big reason I think I

am attracted to textiles is the way they blend utilitarian forms with art. When

I go looking at kilims (I can't afford to look at knotted rugs. If they are

interesting, they are beyond reach), or bags, I am usually attracted to them by

their beauty. Aesthetic appeal (for me) follows my socio/cultural/temporal

perspective. I am a middle aged, classically liberal, New England male from the

academic class. As such, I tend to be attracted by the same softened, pure

colors (likely natural dyes most of the time, though as I have said, I'm really

not qualified to say) that I suspect most collectors out there prefer, along

with the strong geometric designs often associated with 'tribal' peoples. I

have only once bought a textile that drifts too far from contemporary concepts

of beauty (see below).

However, I am also an anthropologist (this is

more relevant here as an insight into my personality than an indicator of

professional affiliation), which means I get pulled in different ways too. The

'ethnographic factor' can occasionally pull me in even if a piece violates

contemporary aesthetic tastes. Last summer I bought a piece my companions found

genuinely offensive. It's a Kurdish Baddanni or Filikli. It's not as nice, but

looks a lot like one pictured in Daniel Deschuyteneer's salon on Kurdish

weavings (which I enjoyed thoroughly--wish I'd been aware of TurkoTek when it

was active). It has wild, synthetic colors (powerful oranges, sadly faded

purples, electric pinks--a member of my project described it as the shag rug

from hell). I love it. I think it looks like it's on fire. However, if it did

not appeal to me from an ethnographic perspective (I thought I knew its use

before reading another salon, which raised alternative possibilities), I

probably would never have looked at it long enough to appreciate its strange

beauty. Understanding a piece's use and cultural context adds enormously (for

me) to a beautiful piece's appeal, and can be enough to get me to part with a

few million Turkish Lira for a less attractive one.

One reason I would

like to see collectors take the ethnographic side seriously is so textiles that

have cultural interest wind up in places where they have a chance to be

preserved. These objects preserve behavior that is currently disappearing, not

just from the contemporary world, but from memory (as elderly people who have

lived a nomadic lifestyle die off). Ethnographic textiles can tell us about

aspects of daily life. They can also tell us about evolving connections to the

larger world, and evolving senses of group identity, and aesthetics. That makes

pieces 'made for one's own use' intrinsically fascinating, regardless of their

current aesthetic appeal. Because some of these pieces are not aesthetically

exciting (or maybe too exciting), at least by 21st-century western collector

standards, they are endangered (does that make them intrinsically

collectible?).

Thank you again for the great conversation. Guess maybe

I'll go register.

Posted by Rick_Paine on 09-26-2002 01:11 PM:

I think both of Filiberto's bags are wonderful. The bright one reflects

the color sense of its maker, which I find fascinating.

The colors

remind me of rugs I've noticed among contemporary Kurds in Turkey. Based on bad

sampling (the handful of houses I have been invited into and rugs hung over

balconies to dry), the big room rug of choice today is a machine-made 'Persian'

with a big central medallion. This is not so enlightening so far, you can see

them in homes all over America too. The difference is the field color around

the medallion. The color of choice--a radiant magenta (bright aquamarine is

also popular). You see these rugs everywhere. I suspect the same sense of color

went into Filiberto's bag.

Woven plastic mats with big geometric

patterns are pretty prevalent too.

--Rick

Posted by Chuck

Wagner on 09-26-2002 06:03 PM:

Arrgghh... ANOTHER century to deal with...

Hi All,

As many of you have noted previously, I'm another who is

undeterred by the presence of synthetic dyes in woven goods.

Our (my

wife generally has a say in what gets bought) criteria for acquistions is not

rigid or closely focused, as our tastes (and our handicraft collection) is

eclectic.

Thus, when we encounter pieces that appear to have been made

for personal use (ethnographic pieces, as Rick mentions) we are quite flexible

with regard to their attributes. Colors and/or designs that clash with our

tastes rarely make it to the counter. The same is true with shoddy workmanship,

or pieces suspected to have 10,000 clones spread around the world.

But

knowing that a lot of folks in the weaving cultures live pretty close to the

edge, economically, we'll make exceptions for pieces that appear to be genuine

artifacts of a disappearing lifestyle.

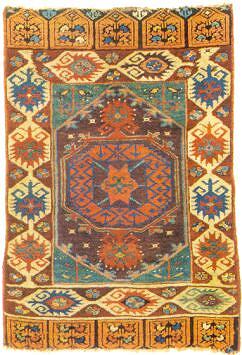

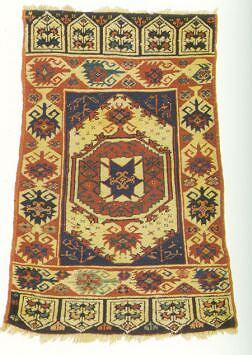

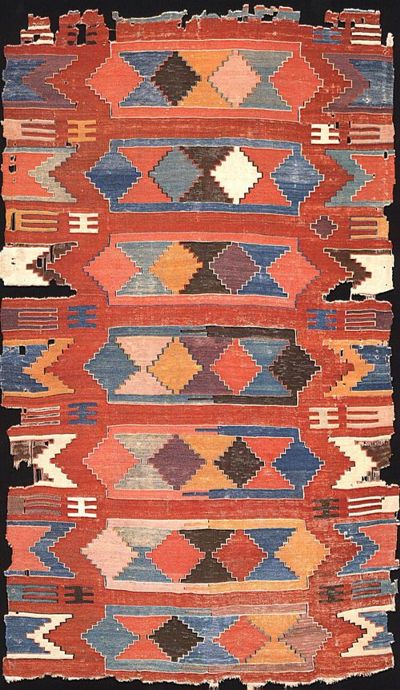

Here are two examples, both

containing a dye that (to my uncertain eye) appears to be fuchsine. I'm pretty

sure they're 5th or 6th quarter 19th century.

The first, I think, is

from north central Afghanistan, probably Ghormaj. A salt bag that has certainly

seen better days but also has the distinct look and feel of something used for

decades. The wool feels like it's still attached to the sheep.

The closeup shows remnants of the original purple color.

The inside is in good shape and shows no evidence of bleeding due to a harsh

wash.

The other piece is a small bag, bigger than a

chanteh but smaller than a khorjin. When I first saw it I thought it was

Chinese because of the sheen on the wool, the velvety texture, and the odd

color scheme.

Then I looked inside...

We don't have too many pieces like these. But then, as

most of you know, they are uncommon (which is different from rare and valuable

) in any market. Their presence is evidence that things have gone so badly in

Afghanistan that the last of the utilitarian goods are going on the market to

raise cash.

) in any market. Their presence is evidence that things have gone so badly in

Afghanistan that the last of the utilitarian goods are going on the market to

raise cash.

The 20th century is one where commercialism and synthetic

dyes dominated the weaving world. Yet nomads still wandered the steppes and

mountains, and poor settled people still made goods for their own use.

Ethnographic goods were still created.

As Steve points out, products

with synthetics are aging into the antique period now, and may gain additional

audience as a result. We should expect more and more queries from people who

seek knowledgable commentary on pieces from the "post-natural-dye" period.

With sufficient study, I suspect we will attain some level of

satisfaction with our ability to establish dating and attribution criteria for

some groups of 20th century rugs. As the weaving cultures comingled and

traditional classification techniques (design, structure) became less useful,

were not some other patterns beginning to develop ?

This will be the

challenge of antique weavings from the 20th century. We should hone our minds

now, while the weavers are still alive to talk to, so when the questions start

coming we have some ideas.

Let's assign a grad

student...

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck Wagner

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 09-27-2002 10:18 PM:

Apples or Oranges

Dear Rick and All- This aversion to artificial dyes and latter weaving

is understandable, but I think it is important to keep things in perspective,

so as to neither confuse apples with oranges or misconstrue the proverbial tree

for the forest. While most would agree that the natural dyes of old yielded the

best colors and in many respects differientiate the truly old or early,

especially among Turkmen weaving, from latter antique or modern weaving,I think

that it is important to remember that these early Turkmen weavings are both

quite rare and quite expensive and as such constitute a smaller percentage of

all rugs and are not representative of the body of Turkmen weaving as a whole.

So when we try to compare an early 19th century Tekke to a late 19th century

tekke we are confusing categories, comparing apples to oranges. Also, I believe

that latter weavings have much to commend themselves, and are most worthy of

collecting, even if for no other reason that they represent a continum. In as

far as these florescent dyes are concerned, it is my understanding that people

in the rug producing portions of the world like these colors, and that is why

they use them. At one time in the not too distant past here in the west,

florescent colors were considered stylish, and if you like them, by all means

collect them. Collect whatever category you like, be it pre 1860 natural dye,

enhnographic, or any number of variations,find the best examples you can and

most of all collect for yourself. Ultimately you are your own authority.-

Dave

Posted by Michael Wendorf on 09-29-2002 11:37 PM:

apples and oranges

Greetings:

It is exciting to hear from a new contributor who is

or has been working and living among the Kurds in SE Anatolia.

While i

agree that anyone can collect anything they find to be compelling or of

interest, I have to wonder about the ethnographic interest as well as continum

that David mentions in connection with weavings with synthetic dyes. What

exactly is it that makes these weavings ethnographically significant or part of

a continum? If Kurdish weavers, by way of example, wove with natural dyes from

local sources and from local recipes for centuries or even thousands of years

only to have these dyes and recipes lost as they were quickly replaced by cheap

synthetic dyes from European companies what is it these weavings represent? The

destruction/loss of a dye tradition? The loss of a way of life? Not much to

celebrate it seems to me - and that quite aside from any aesthetic issue at

all.

Regards, Michael

Posted by R. John Howe on 09-30-2002

06:50 AM:

Michael -

One would certainly have to agree that there is

ethnographic loss when European dyes are substituted for those produced

traditionally within the particular rug weaving community

(Although

note that we seem to acknowledge at the beginning that many rugs we would

consider still to have ethnographic significance were not necessarily woven

from the wools of the weaver's own flocks or dyed by the weaver's own hand and

that likely did not go on "from antiquity," so there is some likely change from

earlier ages of the tradition reflected even in this beginning position. One

might hold that the fact that the dyes came from local Jewish dyers rather than

from European firms is only a matter of distance, that the local Jews were

outside the Kurdish tradition too).

But would you argue that the entire

ethnographic significance of the rugs we collect resides in the character of

the dyes alone?

It seem to me that the enthographic significance of

something is likely based on multiple indicators. Some of these might be the

quality and character of the weaving, the designs, some indication perhaps that

an item was used, etc.

How would you evaluate a piece that is made

using "weftless sumak" but that has some recognizable traces of synthetic dyes,

some goat hair and some places where undyed wool has been used?

I have a

Tekke torba that seems likely to me to have been woven mostly with synthetic

dyes about 1910. It may also have been chemically washed. To make my confession

complete, it was an early purchase, and I bought it because a I liked its

"coppery" color.

But the technical quality of the weaving and the drawing on this piece are both

admirable, it has a rather unusual gul device, and there is some organic matter

in the bottom of it (it is complete with its back) that makes me think it was

used. This is not a piece over which advanced collectors would salivate but has

it lost all of its ethnographic significance?

But the technical quality of the weaving and the drawing on this piece are both

admirable, it has a rather unusual gul device, and there is some organic matter

in the bottom of it (it is complete with its back) that makes me think it was

used. This is not a piece over which advanced collectors would salivate but has

it lost all of its ethnographic significance?

Is the ethnographic

significance of a piece utterly sundered by the discovery that it has some

synthetic dyes in it?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by

Steve Price on 09-30-2002 08:17 AM:

Hi John,

I would go even further than you along this line. Tribal

and village weavers hopped on synthetic dyes like chickens on June bugs. They

did so because they liked the colors and couldn't get them from natural dyes.

That is, the synthetic dyes (at least, until they faded) represented their

personal preferences. They still do.

I don't think synthetic dyes became

cheap to these people until some time later. When that happened, of course, low

cost became another factor.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 09-30-2002 11:25 AM:

To dye or not to dye

Hi Steve,

Right, "they liked some synthetic colors and they

couldn't get them from natural dyes."

And there’s the rub. "They still

do."

Remember those rugs from Salon 64?

Yet, there are collectors who

reject some textiles not for the ugly colors (see above) but only under

SUSPICION that some dyes could be synthetic.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 09-30-2002 11:44 AM:

Hi Filiberto,

The aesthetics of the colors aren't the whole

story. A lot of folks want antiques, and only antiques. Besides, nobody wants

to overpay, and an antique has a higher value than something too young to be an

antique.

When someone says that he suspects that a dye is synthetic,

his real concern is that the piece isn't antique. He may not want it for that

reason, and he surely doesn't want to pay the price of an antique to get

it.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on

09-30-2002 01:49 PM:

You Guyz Are Full Of Surprises

Steve, et all:

...Good. Now we're back to my last point: Now

that the world of synthetic-dyed rugs is creeping into the antique zone, what

(if anything) should Turkotekkes do to maintain the high standard of Guru-ocity

that has been the tradition here, when dealing with 20th century pieces

?

This group loves a challenge, and besides, there ARE some real works

of novel, unique art out there in syntheticville (in both the aesthetic and

ethnographic categories). Is an ordered approach of any value, and worth the

effort ? Should we develop a vetted image gallery for use in establishing age

related trends in colors, design, materials, etc. Do Steve and Filiberto have

endless time to spend looking after such a thing ?

That kind of

stuff...

So, I think it's worthy of some discussion, possibly in another

thread. But if I'm the only one that thinks so, I'll just pull the handle and

not worry about it

Regards, Chuck

p.s. I can't believe ONE of you hasn't given me

some guff over that beat up old salt bag yet. You all must be tired...

__________________

Chuck Wagner

Posted by Steve Price on 09-30-2002 02:20 PM:

Hi Chuck,

John Howe did a Salon not terribly long ago on the

subject of what collectors will be collecting 100 years from now. That's sort

of along the lines that you suggest. If you'd like to work up an essay more

directly in keeping with your idea, I'd be happy to run it.

I think the

salt bag is OK, but not to die for.

Regards,

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-01-2002 09:52 AM:

Hi Chuck,

Why don’t you give it a try?

I’d like also

to see some of Rick’s Kurdish stuff.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Bischof on 10-01-2002 04:32 PM:

another approach

Dear all,

this is an ever lasting topic - and I like it like that

!

Chuck Wagner: here comes the guff. I find the salt bag u g l y - and

the two pieces that Filiberto Boncompagni shows do not convince me at all. With

his estimation of the first piece I agree.May be a proper decent wash to revive

the colour could improve it a bit ? Anyway, not the best of its type. The

second one I do not like. Better: I cannot like it as it looks

"wrong".

2 years before we had a fashion here: traditional "geometric"

carpet and kilim motives on pullovers ( machine knit, synthetic dyes, combined

for a pastel elegant European indoor look) . It really hurted my eyes: it

looked "wrong". The motives in a way do not function with these dyes. May be as

they arose from a kind of co-evolution with strong natural dyes ?

This

tradition is at least 4000 years old ( I speak of weaving using dyed fibers)

and within this time span a sustainable result evolved: harmonious combinations

of upmost saturated natural dyes, applied in tricky and lengthy processses (

that did not harm the fiber integrity). This can be seen best in not (!)

patinated (light-oxidized, damaged) pieces but in mint condition though their

number is indeed very small. " we both admire the gentle pastels into which

many natural dyes fade with age" ( R. John Howe) is a description of the

attitude that the majority of collectors hold. But in science and art it is not

the majority that counts. Great dyes do not (easily) tend to develop gentle

pastels. Look at some great early 14.-17. century fragments - but, please, to

the wool inside the pile, not at the surface (though many of them even there

have an intensity that is breath-taking).

The more "pure" the natural

dye is the more costly it is to make it, leaving the necessary know how aside.

With natural dyes one can make even stronger pink colours than the piece of

Filiberto displays - but such a dye this weaver could not have afforded, at

least not to use it in these high amounts. Some jewel like tiny spots,

highlights....

This is an aesthetic approach. It has nothing (!!!) to do

with age ! Great creativity was extreme rare in old days and today ... only a

fool would reject a splendid weave because it is new. 200 years before people

used better dyes for the simple fact that the quicker, lower quality

substitutes were not available, yet. Please do not forget that the essence of

industry is to substitute human labour - at the expense of quality in most

cases, at least with textiles.

"Ethnographic" value: if it is no weak

excuse for aesthetically wrong selections there must be a "story", a background

that proves the significance of a particular "ethnographic" textile ( no matter

whether there are synthetic dyes in it). This story, of course, should be so

that it can be checked in order to avoid

tapetological fairy

tales...

Michael Bischof

Posted by Rick Paine on 10-01-2002

07:39 PM:

Two quick points:

1: One's individual aesthetic taste is

important, and it is an appropriate (probably the best) basis for collecting.

It is also highly culture specific. One learns to appreciate colors, (or

musical styles, or the shapes of the opposite sex) favored by their 'peers.'

This sense serves as, among other things, a means of identifying other members

of the 'in' group ('us' from 'them'). It lets one know who is an acceptable

friend, ally, or mate.

Let me give an example from an utterly unrelated

area. Classic Maya nobles had a rather different idea of beauty than

21st-century Euro-Americans. The found an elongated skull and receding forehead

ideal (all with hand tools!). They also filed their teeth into different shapes

and inlayed them with green stone. Having the right forehead was as clear a

status marker as knowing which fork to use has been more recently. When I tell

my students about Maya fashion trends, I invariably get audible groans from the

room. My reply is this: we live in a society where people surgically implant

sacks of jelly in their breasts and have their teeth filed to nubs and replaced

with ceramics, wear high-healed shoes that destroy their backs, and where their

parents chemically curled their hair (how you feel about any of these things

probably says a lot about your specific social group too). Our fashions would

probably be as repulsive to the average Maya as filed teeth are to us. The

point is if you JUDGE other culture's aesthetics (what you choose to put in

your own home is a separate issue), you have missed some important

points.

2: Cultures are dynamic entities. Styles change when new groups

or ideas pop up, or when individuals defy established norms and experiment.

They also change with technology. The process of change, whether caused by

social change, technical change, or something else, is not only normal, but

absolutely fascinating to many of us. To suggest that a culture (or an art

style) has somehow devolved because it has adopted technology or patterns that

do not appeal to US (this has an incredibly long tradition in Art History) is

horribly ethnocentric.

By all means collect what you like. If I can

borrow a digital camera and figure out how to post some pictures, we can have

some fun critiquing what I like (those hoping for a collection dominated by

shocking pinks will be disappointed). Personal choice is fair game--and fun.

But, be careful about blanket statements about whether other cultures are

degenerated because they chose a technology, or a new palate of colors they saw

as a benefit.

I have to go find a pigeon so I can post this.

Posted by Michael Bischof on 10-02-2002 02:54 AM:

Dear all, dear Rick Paine,

thanks a lot for your welcome

statement !

To warn against ethnocentric remarks is important, indeed.

But the adressates of such warnings are not people that uphold natural dyes -

the ethnocentric crowd is made up from those who come with claims like "this is

art ... because it has some impact on me!" and who therefore try to put down

all efforts to determine the significance of a certain textile (piece of art)

within its original context ( as far as we can research it ).

To warn

me against it is like taking owls to Athens. I lived from 1992 - 1998 in the

Türkmen Evleri Mahalle in Karaman and work together with weavers in the

Karaman/Taskale area till today. So I could do more than sitting in Germany (or

America) at my PC and start to speculate whether and why weavers in the remote

Near East would like natural dyes or synthetic ones. We could test

it!

The result is crystal clear: - where they have a chance of selection

they prefer natural dyes (in case these look like what they have in mind: a

real red, no "production red" (1), a splendid real violet from madder only,

blue Indigo hues that do not inflame your skin ... as mentioned before: in

Karaman the ladies in the neighbourhood constantly come to the master weaver

with whom we work together, Susan Yalcin, to catch a bit of strong natural dyes

and knit it into pullovers. Not into the cheap commercial rugs they weave for

some Istanbul firms and not into their own little rugs - as they are too

valuable for that, today.

And: the yarns should be clean, you hands

should not appear stained in the evening. This is the reason why today local

weavers reject (if they can) the contemporary offers of Turkish carpet

producers who use these "amateur" natural dyes. - in old days and today the

weavers/knitters had no access to the most important dyes. But in old days

there was no alternative to natural dyes - today there are a lot, and these are

cheaper! - one can combine excellent natural dyes in whatever crazy

combinations in case they have, more or less, the same grade of saturation -

with harmonious results. Of course it is possible to make ugly weaves with the

best available natural dyes, e.g. if you apply too many without creating a

recognizable image. But this is difficult - with synthetic dyes it is easy to

create ugly results, as the given pictures show.

If you are not

convinced: - look at the shocking pictures Filiberto Boncampagni contributed.

And then imagine the same weaves done with natural dyes, but imagine pieces in

mint condition! - you gave a good example: a baddani with shocking synthetic

dyes. Now imagine one would do such a thing, using silky Mohair and natural

dyes, expertedly done in order to come close to the overall look of your

baddani. This is no theory, please. It could be done! Take my words as a kind

of bet. But then the price would be like with an antique piece. The look will

be very different, though.

Of course culture is and has always been

changing. To follow it is a fascinating field! But when you change basic

technologies there is always the risk of mishappenings: evolution produces also

a lot of "trial-and-error"-results that do not survive, that are not successful

... as long as it takes to achieve a successful new identity on the basis of

that new technology. My thesis is that we should judge these synthetic dyes as

such mishappenings - and, in certain, well researched ( !) cases, may estimate

certain exception for their creativity, other aspects of a special meaning ....

What a certain individual collects or not will, of course, remain his

private obession and right. I like the idea of "good taste" - as long as it is

not dictatorship. Personally I own some ugly artifacts because they remember me

of certain situations that I like to remember. But, damned, that does not make

them beautiful.

Michael Bischof

(1) Production red ( "imalat

kirmizi" ) is an insiders term of carpet producing people in Turkey. It

describes the result of what you get if you follow some Western hobby dyeing

recipes with madder plus try to save money by using the lowest possible amount

of expensive madder when doing it. A kind of matt, brick-"reddish"-"brownish"

something ... by light oxidation it changes in short time to a clearer red but

on the expense that roughly 30-40% of the dye lake amount is killed and the

fiber looks spotty, then, as this process is uneven. To overcome this problem

most guys add some synthetic red dyes on top of it. It is called

"köklü" boya then - what means: the dye contains madder. "Kök

boya" would mean: entirely from madder with no (!) synthetic additions. This is

an old habit: when the newly found azo dyes were applied in the Orient at the

beginning people liked very much the pure, "shocking" impact they had. But they

faded quick. It did not take more than 10-15 years to have a more rational

method evolved: to drop the dye costs by using only a small portion of madder

in a quick (!) process and then top the unsatisfactory result with some azo.

This we often find in end of 19th century woven Caucasians and Turcomans. Rick,

sorry, this is second ranked: because it looks so!

Posted by Chuck

Wagner on 10-02-2002 05:43 AM:

Michael,

Your comments don't address the ugly rugs made with

natural dyes, (and there are LOTS of them) and how it is that they can be made

with natural dyes and STILL be ugly.

And, you seem to be missing Rick's

initial point, which was that when collecting pieces from a cultural

perspective rather than a narrowly focused aesthetic perspective, the natural

vs. synthetic dye argument has no meaning. It becomes a question of practical

use as an indicator of age and cultural origin.

And then there's

Filiberto's point, which was: Maybe the weavers use these colors because they

LIKE them. Certainly, there are occasions where weaving is done under contract,

and the weaver has no control over materials. But the Qashqai CHOOSE to weave

with garish colors. I do not think it's because they've been watching too much

MTV. It would be simple to use sombre synthetics, as the Baluchis do. The

bright colors are used because they LIKE them.

This is not to say your

thoughts are wrong. Your own experiences clearly shape your opinions. And,

every collector sets their own standards.

Last, I agree with you

regarding the aesthtic appeal of the salt bag. But I didn't buy it because I

thought it was pretty. I WOULD like to know if anyone agrees that the purple is

in fact fuchsine because, if so, it puts an age bracket on the article in

question.

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck Wagner

Posted by Michael Bischof on 10-02-2002 10:38 AM:

ugly rugs

Hi everybody, hi Chuck,

well, my language might not be precise

enough: I mentioned the possibility to create ugly rugs from splendid natural

dyes as well. That it happens is quite unlikely, but possible, yes. To create

handsome, not to say beautiful, rugs with synthetic dyes is extremely

difficult. One must (!) use other motives then. The traditional ones do not

"work" as the examples show.

Cultural perspective: always welcome! But

this one would like to see in a way that can be checked and discussed, not as

an empty claim. Sounds nice: but then you should not just show or mention the

piece. You must add the background story. Because, on its own, the piece does

not deserve attention.

Filiberto is right: in these +/- 4000 years

weavers learned that it is a kind of hard fight to release pure, shiny dyes

from natural sources. The more pure the harder it was - and therefore more

expensive. As people always fight (or prefer) what they do not have such a dye

in pre-industrial times were most likely visual status symbols. But when their

cheap substitute became plenty the uncontrolled use of it killed the aesthetics

...

But again: a striking pink made in a special way, let us assume from

Cochenille, is light years away from these cheap pinks, visually and in its

performance! So to use it would give a different result. Of course how to use

it needs certain self-discipline. But this one needs in each art. Who cannot

master it ... from the distance I must say what I have said when living and

working at the spot: "authentic" is not automatically the same as "splendid" or

"successful". Gashgai women are not the only ones that produce Kitsch although

they are, technically, master weavers. In Karaman I saw shocking examples of

that as well. In case such people lose against an alien culture, accept its

predominance and try to copy elements of it - why should we admire the results

of that attitude? To admire the physical beauty of those girls seems to be a

better alternative - for me at least.

I do not dare to comment on the

fuchsine problem from this picture. The bag looks like a typical "semi-antique"

piece: 20-80 years old, done with synthetic dyes, faded in use ... it does not

smell that one would find fuchsine in it. Nevertheless: if the situation when

you got it was such that you would like to remember it - fine.

Yes, and

here is the problem. In my opinion we discuss such things here in order to

develop standards, measures, etc. Pieces with synthetic dyes do not contribute

to that - unless they are embedded in a "cultural perspective". But again: this

must be displayed then!

2 years ago there was a well announced

exhibition of yastiks in Northern Germany. Some 20 or so pieces. Only 2-3 were

natural dyes, but they were not top pieces. All pieces had been bought in the

trade, in Turkey in most cases. Their real origin, everything else .... was

unclear. Except some that were, with precautions, defined by some of the

viewers. Where, please , is the "cultural perspective" here?

The

synthetic dyes made the pieces aesthetically uninteresting. Such things might

be valuable - together with a proper, well documented background story. But by

occasional buying in touristic carpet shops one cannot accumulate it. What is

left then?

By the way: it was no idea to drive 400 km to see it. If I

would have known ... or, better, if the unlucky collector would have followed

the advice of Michael Franses (like: study the subject as well as you can and

then buy the best that you can afford) - then I would have in my brain 2-3

great yastiks that since then I wouldn't have forgotten.

If Rick Paine

would use his free time while being there, learn the local language, group some

co-workers (some ladies must be in the group! Turkologists as well, for the

important details of local language) and would start field studies - yes, then

there would be a "cultural perspective". But the measures should not be lower!

In this way one could well collect material for articles, for an exhibition.

But this would not be related to art. A proper title would rather be "Status of

the local cottage industry of ..... at the end of the 20th century". The bulk

of Caucasian weaves from the second half of the 19th century, by the way, would

fall into this category as well.

"And, every collector sets their own

standards." What someone chooses to collect is, of course, his own choice. What

he claims it to be is not his choice - it can be discussed and, well, be

rejected.

Michael Bischof

Posted by Michael Bischof on

10-02-2002 12:31 PM:

Hi Chuck,

sorry, I did not put enough attention on your first

sentence

quote:

Your comments don't address the ugly rugs made with

natural dyes, (and there are LOTS of them) and how it is that they can be made

with natural dyes and STILL be ugly.

as I see now.

Postponed, not forgotten!

Please be more specific: what "natural dyes" do

you mean ?

Do you mean

"natural dyes" as to be seen in todays commercial fashion of Near

Eastern carpet producers?

- Or do you mean "natural dyes" (sensu strictu) in truely antique

pieces or done today with methods equivalent or even superior to those ?

This makes a big difference. Let me start with what one can learn

from old pieces. All early Turcomans, for example, have ultimate saturated dyes

of varying degrees of "purity". In addition the very early ones display a more

free ( but still very disciplined ) use of them. Same with Balouch. The latter

prefer such dark combinations that they should be viewed in bright sunlight !

Otherwise they do not "work".

If you compare now late pieces you will see,

I guess, that these in most cases have less saturated, but often ( with the

help of azo-topping) more "pure" dyes. As the synthetics fade what is left is -

I speak of truely antique, but late pieces here ! - a disappointing "flat"

appearance.

Now imagine you take a little thing, e.g. an 18th century

Salor or Arabatchi cuval, to a carpet shop and put it on top of

modern "Turcomans" or "Caucasians" from Pakistan

- modern kilims from Iran or Turkey

- late 19th century Turcomans or Caucasians (the usual auction stuff,

to sum it up)

I think you will immediately get my point. With the cottage

industry of today we have another problem. Tradition is the source for boring

repetitions - but at the same time, as people tend to repeat "successful"

combinations, a source of protection against "wrong", ugly combinations. This

idea works only as long as one does not change the material basis.

A

lady that is accustomed in her habits of placing colours to saturated dyes, but

the enterprising firm gives to her flat dyes for price reasons (and for

contemporenous Western taste that mistakes harmony with "pastel"= flat dyes),

then a successful combination changes to an ugly one. And now imagine what

happens if you leave the authentic weaving areas and move to the big successful

field of modern "uprooted" carpeting (Pakistan,India, China - but similar

concepts in Turkey or Iran as well). The aesthetical fiasco that comes up then

has nothing to do with natural dyes - any saturatedly dyed silk shawl or fabric

will prove that!

Michael Bischof

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 10-03-2002 03:14 AM:

Hi Michael,

So, you agree with Chuck on that one,

right?

Frankly, there are some examples of modern and expensive high quality

production with hand spun wool and natural dyes that make me SCREAM of horror.

Three of them are here:

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00070/salon.html

For

our policy, I’m not going to indicate which ones, though.

But to go

back on your opposition to artificial dyes:

1 - If you speak from the

point of view of ethnology, their presence is irrelevant, as Rick already

pointed out.

2 - The same if you speak from the artistic point of view.

Otherwise, with a similar logic we should discard - say - impressionist

paintings or modern music, because the firsts were made with new synthetic

colors and the second uses electronic instruments.

Then there are things

I’d like to clarify.

To be perfectly sure about the "syntheticity"

of dyes one has to perform a chemical analysis i.e. appearance cannot be

trusted. This was discussed on Turkotek some time ago. I remember someone spoke

about artificially looking dyes (perhaps on a Kaitag embroidery) that a test

shoved to be natural.

I also remember that synthetic madder and indigo are

more or less the same than the natural ones - (chemically they have the same

composition only purer). So, it’s difficult to discern natural from

artificial.

Ultimately, my opinion is that all depends by the way the dyes

are applied on the wool and by the quality of the wool itself.

Also,

when you write "The synthetic dyes made the pieces aesthetically

uninteresting." I would like to understand how much of synthetic dye makes a

rug unappealing for you.

I mean, in old textiles natural colors can be

found along with artificial ones. How much of the latter bothers you? A few

knots, like in some Baluchi rugs? Some specific colors? 5%, 10% of the whole?

Or isn’t it better to judge case by case?

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Michael Bischof on 10-03-2002 08:52 AM:

Dear all, dear Filiberto Boncompagni,

first of all: I have no

opposition against synthetic dyes. I do not put them on the same level with

first class natural dyes, that is all. Like I do not place "slow food" and

"fast food" equal. I do not exclude, however, that artistically great solution

might be found with synthetic dyes - but not using the traditional imagery of

Oriental rugs and kilims.

One example that comes to my mind are Bauhaus

carpets, done with machine spun wool and synthetic dyes in the twenties in last

century. They had a modern designs that fitted well to the colours they used -

not exciting, but pleasant, I would guess. Their estimation in the market needs

a kind of prove what they are - in other terms: they are not overwhelmingly

"self-explanating".

How weavers get their dyes is one not unimportant

part of the material life and therefore not unsignificant for ethnographers.

For its evaluation of its "ethnographic value" it would be insignificant. I

agree.

That you, Rick Paint, did not discuss the economical impact of

synthetical dyes on weaving communities I excuse with the fact that you are an

archaeologist and not, in first line, a textile researcher. In old days, before

synthetics were introduced, weavers could occasionally sell their goods. It was

similar to have some money on a bank account. The amount of labour spent for

weaving was not lost. After the synthetic fiasco this chance has been lost.

First the aesthetical value dropped, then the economical value followed. Today

textile items with synthetic dyes are meaningless as a kind of "depot". The

dealers just sit and wait. In the "dry period", before the harvesting period

starts and fresh money comes, villagers are forced to sell for absolutely

ridiculous prices - otherwise they cannot sell. This makes them stop to weave.

The woven items are therefore (inside such a community - not for the touristic

retail customer, of course) a kind of a waste business. How often did we guide

Westerners to Anatolian villages and always run into the same old problem:

women want occasionally to sell some of their goods (canta, heybe, cuval,

sometimes bigger items) and are absolutely disappointed that the customers do

not want to offer fair prices. Why? Because the same goods are so cheap on the

market (plus the idiotic expectation of "buying at the source"). This

combination kills, at the end, the skills... and which private firm, who would

need to safe-guard talented weavers at the end, would dare to give to them

naturally dyed yarns? Let us assume Mr. Miller would come across such a new

heybe, splendid as he ever ever saw any antique one (most of these are

extremely faded by use). What would happen ? He would reject it for being

new.

Your example with impressionists painting therefore lacks one very

important aspect: these people did not copy traditional painting styles with

new materials - they developed a new style together with these materials. And

this did not yet happen with synthetic dyes in the carpet environment. So your

argument nolens volens emphasizes mine: that changing the visual basis (dye

technology) without changing motives and colour combination killed the

aesthetical values. No wonder that the unhappy corpses of such enterprise must

be further tortured by sun tanning on the mountains .... which hurts the

integrity of the wool in addition to the chemical wash attack.

I have

not enough understanding of modern music to be able to comment whether your

comparison is suitable or not. But isn't it a bit fresh for evaluations ? I

mean such things are established some time later - looking back one is most

often amused about the measurements done at a certain time. I am for sure not a

"tradionalist" - but we discuss a defined topic. And there I still wait for the

advocates of synthetical dyes to come up with something convincing,

aesthetically ... and when it comes to "ethnographical perspectives" I simply

want to see them.

Of course natural dyes in a piece can result in

a fiasco. If you would read my text again you will see that I had mentioned

exactly that. Simply because I had some of the examples in my mind to which you

refer in R. John Howe's excellent salon of last year. But the examples that you

cite deviate from the assumption that I had in mind:

* there is

not one piece there where the weavers did decide how to use the colours. These

are cottage industry products ...

* there is one (half) exception: the

Ersari piece where traditional motives and colour combinations have been used -

and it is does not hurt your policy if I state that this is not a fiasco piece,

is it? In my opinion the only visible deficiency (but notice, please: on the

basis of a digital photo I do not base such a statement!) seems to be that the

colour saturation is not high enough, as compared to 2nd half of the 19th

century Ersari pieces. Especially the pale orange in the end kilim looks a bit

"flat" for me.

What I had in mind is the case when Oriental weavers have

the chance to combine saturated natural dyes (not those of todays cottage

industry!) in the way they like when they create weaves which must not copy

traditional designs, but that are based on these design schemes. There is so

much space for creative evolutions within this frame !

Michael

Bischof

Posted by Michael Bischof on 10-03-2002 09:56 AM:

Hi everybody,

here comes part II ( I still need to practice vB-Code,

forgive me).

quote:

So, it's difficult to discern natural from

artificial.

No, but it needs "training". To compare

synthetic alizarine with madder is kind of misinformed, as well as to compare

natural Indigo and synthetic Indigo. But, as Filiberto writes:

quote:

Ultimately, my opinion is that all depends by the

way the dyes are applied on the wool and by the quality of the wool itself.

That is the point - and a trained eye can immediately

visualize this difference ! For a court trial we would need an expensive

analysis. In the market reality things are different: because there is a

big difference between natural Indigo, knowledgedly vatted using organic

auxilliaries, and synthetic Indigo the repair people in the Orient, who did

never learn how to make dyes, are forced into extreme dangerous and

toxic manipulations to obtain a nuance that looks closer to the "old"

Indigo hues than the modern synthetic Indigo/caustic soda/hydrosulphite process

would yield. They heat synthetic Indigo dyed yarns in potassium bichromate

solutions ( the ultimate co-allergenic and co-cancerogenic

substance ! Nanograms should be avoided, at least in daily exposure till

this strong oxidizing agent kills the Indigo and, unavoidably, a part of the

wool as well. But the resulting shade is more greenish, kind of broken, closer

to an "old dye".

The simple fact that these professional people expose

themselves to such a danger shows what the market thinks of the aesthetical

values of synthetic dyes (even if they have the same formula like their natural

idol ).

Of course I did not have in mind a percentage up to which a

synthetic dye would not bother. I have seen once a Lenkoran carpet, with

splendid real (!) Cochenille as a ground colour, superb saturated flavon

yellows ( may be from weld ,or from local sources), and reported at the ICOC in

San Francisco about this piece ( as a part of a technical review about HPLC

application for researching natural dyes). There were tiny spots of "shocking"

reddish-orange spots in the border - in analysis it came out that it was very,

very early azo, many different fractions, not pure, at the very beginning of

this business). I loved the rug! Outcompeted most of early Caucasians that I

have seen (for the colour impact).

In general "late" pieces have less

saturated (natural) dyes. This reduces the aesthetical value of the piece - if

we have 1% or 5% synthetic dyes does not matter. And, to be frank: the late

19th century products of the Caucasian cottage industry ( the majority of our

"collector's pieces" !) have reds that share the brownish-matt shade with

todays "imalat kirmizi" - if these are topped with a bit azo they look better,

more "original". If there would not be this damned washing problem

...

But with these experiences, measures - and demands - you might

understand why I find any thought of treating the 20-80 years old, mixed

material as "collector's pieces" to be grotesque. They might be "affordable" -

yes, what does this mean then ? The advice of Franses for me seems not to be

snobistic. "Honest" I would call it ...

Regards,

Michael Bischof

Posted by Tracy Davis on 10-03-2002 10:50 AM:

Chuck's salt bag - fuchsine?

I looked back at the photo, Chuck, and although the magenta dye appears

synthetic, I doubt it's fuchsine (which usually fades to a beigy-gray color) -

there's still too much color left. I would guess it to be a second- or

third-generation synthetic (1910-1930ish), but I'm open to argument.

Posted by David R. E. Hunt on 10-04-2002 01:10 AM:

Further Elaboration

Chuck, Michaels , All- First off , Chuck, I like the bag, no weaving

masterpiece but interesting, as long as you bought it at the right price. While

of course it is all well and good to concentrate one's efforts, when assembling

any collection, upon only the best and most valued, rare, expensive,ect., this

does not hold true when assembling a collection intended to reflect the range

of variation exhibited by any order or class of thing or object, be they

insects or carpets, or aves or automobiles. As such with ethnographic textiles.

While it would indeed represent a beautiful assemblage of rugs, a collection of

only those specimens demonstrating the clearest colors and the best delineated

markings would demonstrate all the scientific value, in the least from the

perspective of representing a range of variation, of a coleopteran collection

assembled of specimens chosen for inclusion by those same criteria of clearest

color and best delineation of marking.It might make a beautiful beetle

collection, but it would fail miserably at being anything but the most cursory

and superficial representation of the natural range of variation demonstrated

by beetles.Take it to the Smithsonian and they would laugh. Or perhaps a

collection of Ferrari and Rolle Royce. Much more representative of the tastes

and wallet of the collector than a true representative sampling of the values

and varieties of automobiles manufactured and driven by the populi of America

and Northern Europe in the twentieth century. Rare and beautiful rugs are both

but they are not an all inclusive survey of weaving culture, more at art than

science, and for myself the intellectual compenents of collecting are most half

the attraction. In as far as preference in choice of color is concerned, I

think this best demonstrates a basic quality of human nature as opposed to

color preference, for most anyone would choose, given the option, the Ferrari

over the Volkswagon.-Dave

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on

10-04-2002 03:16 AM:

Hi, Michael,

Thank you for your answer(s).

It seems we might

be able to reach a lowest common denominator here if we do not reject a

priori a rug for the presence of synthetic dye on it.

One has to

decide on the single case, like the Lenkoran rug you speak

about.

Regards,

Filiberto

Dave made a good point too.

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 10-04-2002 07:50 AM:

Get The RayBans Out

Hi Michael,

Sorry it took me so long to get this posted, I’m

coming in about two days later than I wanted to. One thing this particular

exercise has taught me is that Microsoft software developers are overpaid.

I’m going to ruminate a little about the synthetic/natural dye issue. I

note, up front, that my initial impression of your position on the issue has

evolved as you have explained more fully how you feel.

As I am one of

those “A Picture Is Worth A Thousand Words” people, I’m going to

try to get a few thoughts in and then reinforce them with commentary on some

images.

I see that you have stated that you are not rigidly opposed to

synthetic dyes, per se. It is clear though, that because your collecting focus

area is antique carpets, synthetics hold little interest for several reasons,

not simply aesthetics (more on that later).

So first, regarding your

question:

“ Please be more specific: what "natural dyes" do you

mean ?

Do you mean

• "natural dyes" as to be seen in

todays commercial fashion of Near Eastern carpet producers?

• Or do you

mean "natural dyes" (sensu strictu) in truely antique pieces or done today with

methods equivalent or even superior to those ? “

When I say natural

dye, I mean natural dye. A product of minimally processed vegetable or mineral

origin. In other words, not an industrial chemical. Whether the dye was cooked

over an open fire or prepared in a city dyeworks makes no difference to me. Nor

does it matter whether the piece is ancient or brand new. As I stated in an

earlier post, I am not put off by synthetic dyes. But when I can find a

naturally dyed piece, and it’s attractive to me, I’ll buy it over a

synthetically dyed equivalent if it doesn’t leak (a badly fixed natural

dye will run just as badly as a synthetic). But that’s it. My collecting

tastes are quite eclectic and our collection reflects that.

But, I AM

put off by a BADLY DONE synthetic dye job, especially in newer pieces because I

don’t think there’s much of an excuse these days for doing a lousy

job. The chemicals are high quality now, and so are the results when used

correctly. I’m willing to make an exception now and then when dealing with

nomadic or CERTAIN refugee goods, because I know that the conditions under

which the dye was prepared may have been so primitive that quality control was

not on the preparers “important things to think about” list. And,

lack of funds limits some weavers to the cheapest materials that they can find,

which does not bode well for the collector.

What surprises me is the

frequency with which one encounters leaky dyes in new city carpets today.

Twenty years ago, you’d have to look at several hundred Tabriz rugs before

you could find one with leaky dyes. Today, that number is more like thirty. It

seems that the pressure from emerging city carpet look-alike industries in

India, Pakistan, and China, are causing shortcuts to be taken in Iran and

Turkey that were unacceptable not long ago. I’m sure that collapsing

currencies are major contributors to this problem as well. It’s certainly

not because the emerging carpets are higher quality than the older ones from

the traditional weaving areas. They’re less costly. But inexpensive

mediocrity seems to satisfy enough people to squeeze the entire industry. Too

much supply, not enough demand, etc.

Very high quality city goods ARE

still produced. I’ll show you a couple. You just pay more for them now.

I’m not sure we’ll ever be able to say the same for nomadic goods. As

we all know, natural dyes are more expensive and take more time to use than

synthetics. What nomad would vote for losing time out of the day without

adequate compensation ? The economics of competition force the use of

inexpensive methods when the woven product is intended for the marketplace.

When the weaver is also the customer, there IS no compensation. It’s a

harbinger of bad things to come for traditional weavings collectors, because

there aren’t that many people on the planet who would choose poverty over

prosperity. The nomadic lifestyle may continue but I think it’s unlikely

that truly traditional weaving goods are going to be produced in any meaningful

quantity any more. Of course, what that all REALLY means is that the definition

of “traditional weaving” seems to be changing.

Which brings me

to my next point: Time Marches On. As those few REALLY old pieces become

increasingly scarce and prohibitively expensive, the collecting population will

direct more attention to more recently antique pieces. Most of those pieces

will contain some, if not all, synthetically dyed material. So the proper

question to ask is: how do we judge quality, or more importantly: value,

whatever that is, in newer carpets ?

The old measures, to a large

extent, still hold: No leaky dyes, color palette in harmony, lies flat, same

width at both ends, no obvious repairs (if they’re obvious they’re

either badly done or so big you should worry about them, right ?), structure

and materials compatible with the proposed origin, etc.

But for most

20th century pieces, color palettes in particular and materials to a lesser

degree have departed strongly from the old “traditional” ones

associated with weaving groups in ALL the “authentic weaving areas”.

The Baluchi in particular seem to have had their fill of dark colors and have

gone off into new and uncharted levels of intense (and occassionaly absurd)

color combinations (see below). The modern Turkish kilim weavers seem to favor

ghastly combinations of a weird pinkish-gray, olive drab, dull magenta, and

brownish- yellow (and they don’t seem to scour their wool very well. A lot

of it smells as bad as Bedouin weavings). Trends through time do exist however.

One familiar with Nain & Esfahan rugs can, at a glance, determine which 30

year period of the 20th century is the most likely period for a piece. The same

is largely true for Baluchi goods.

Historical events since the mid 19th

century provide us with several identifiable populations of woven goods, which

by virtue of their cultural connections will drive collectors interests. These

events have often had negative impact on the weaving societies, however, and as

a result the products often contain features usually shunned by collectors.

Example: Afghan war rugs. From a historical perspective, a point source event

almost unique in the weaving world. Result: rugs with poor dye jobs. And, a

unique marker in the weaving world tied to a specific event in time. Maybe

Filiberto can comment on this: Here in Saudi Arabia, war rugs are now very

scarce. The Afghanis have moved on to decorative carpets and interesting

mixtures of natural and synthetic dyes. The refugee situation has actually

created a new production area that generates new versions of old Caucasian

designs, and designs & colors similar to those produced by vegetable dyed

rug producers in Egypt and India. And the quality is coming up quickly. Six

years ago the dyes ran and the finish work was shoddy. Now the dyes are stable

and the finish work is excellent. I should point out that the Afghanis in the

rug trade over here have relatives back home who are really looking forward to

getting back to the traditional designs & color palettes of Afghan rugs.

Many lost all their looms and goods during the late unpleasantness and as a

result there has been a dearth of well made “red rugs” over the last

20 years. So there is a “cultural driver” that at least partially

motivates these folks to continue traditional methods.

Which remindes

me: I would like to point out that I do not equate the notion of a collecting

with a “cultural perspective” or rather, a focus on a specific

culture, with the notion of developing a rigorously researched and documented

provenance. This is not required unless the end owner is a museum, a person

with highly specific collecting criteria, or someone whose net worth has been

materially reduced by the acquisition in question. Thus, I do not agree with

your statement:

“Cultural perspective: always welcome! But this one

would like to see in a way that can be checked and discussed, not as an empty

claim. Sounds nice: but then you should not just show or mention the piece. You

must add the background story. Because, on its own, the piece does not deserve

attention”

Clearly, whenever a background story is available and in

particular, verified, there is added value. But most stories are part fact and

part conjecture. Much of the carpet collection world is partially submerged in

conjecture. The idea, for example, that old Turkoman pieces were not made for

commercial purposes and are thus more valuable than those made after the

mid-19th century is notable for ignoring the fact that Central Asian cultures

have been trading textiles for centuries. The Scyths, Sogdians, Greeks, and

Persians traded a variety of goods commercially more than 2000 years ago. Is it

REALLY reasonable to assert that Turkoman textiles of the 17th and 18th century

were made solely for personal use, and thus are more ethnographically valuable

than those of the late 19th century ?. Who knows how many weavings were

ACTUALLY made for the purpose of barter or sale ? It APPEARS to be less likely,

statistically, but only because we have knowledge of the scale of the

commercial weaving environment of the late 19th century. The Turkoman traded in

horses and wool. Why not weavings, even amongst themselves ? I don’t

believe that EVERY Turkoman woman was a great weaver. Those that weren’t

may have had to barter with those who were in order to outfit the oy properly.

If so, then those weavings were done with commerce in mind.

If we are

uncertain about personal vs. commercial motivation, how certain (or inflexible)

can we be about what is “true art” and what is transplanted art ?

Does commercial motivation negate the possibility of “true art” in a

piece. It’s a question obliquely related to Filibertos point about the

impressionists. Not only did the impressionists use new materials, they used

them to pay their rent. You reject this analogy thusly:

“Your

example with impressionists painting therefore lacks one very important aspect:

these people did not copy traditional painting styles with new materials - they

developed a new style together with these materials. And this did not yet

happen with synthetic dyes in the carpet environment.”

This comment

serves to deflect Filibertos actual point. The impressionists were not the ONLY

painters on the planet. Others who continued in the classis design motifs ALSO

switched to the new materials because THEY were starving artists as well. The

new materials made inroads because they were considered acceptable by their

user. It was their choice, as the artist, to make the change and that does not

make them lesser artists.

But it does mark yet another turning point in

time that is unlikely to be reversed; the same is true in the dye industry.

Remember that the reason this happened to begin with is greed. The persons who

cultivated the madder, weld, indigo, etc., put themselves out of business by

squeezing the market to such a point that alternatives were developed. Oil

producers should take note.

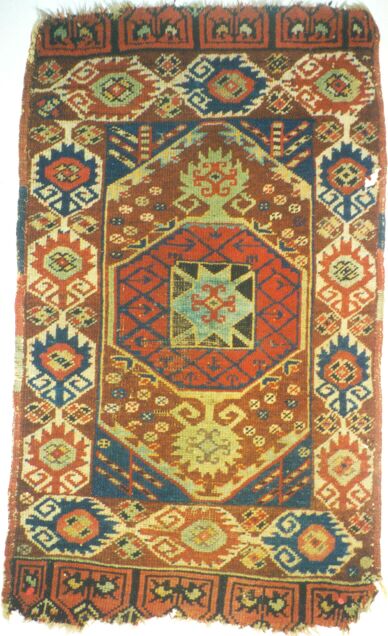

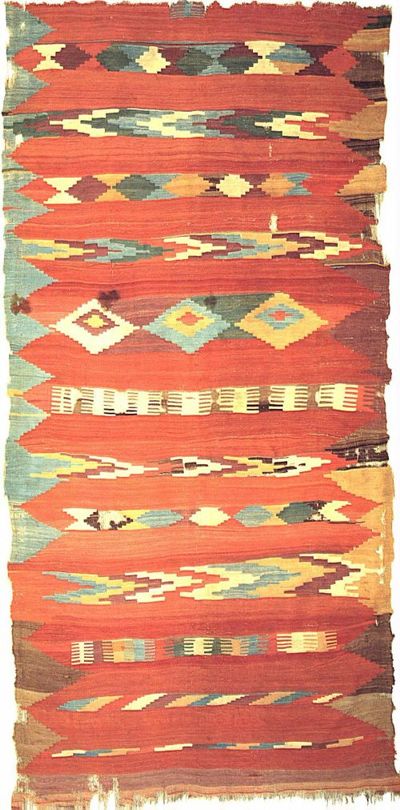

So, enough diatribe. On to the images.

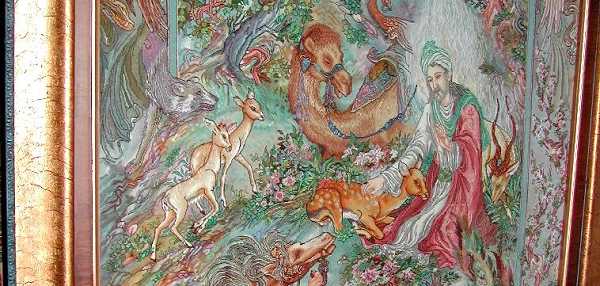

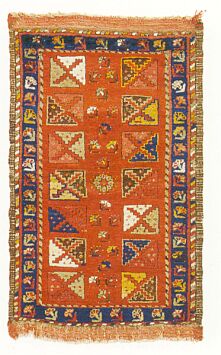

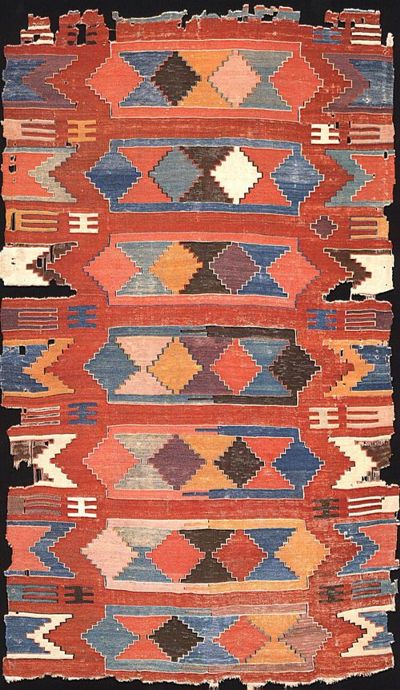

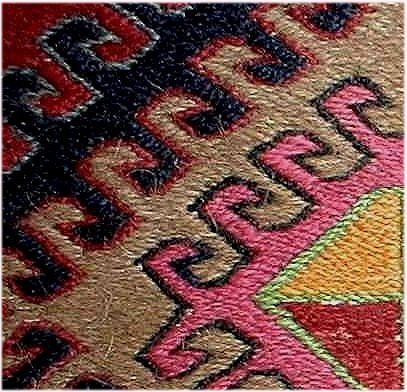

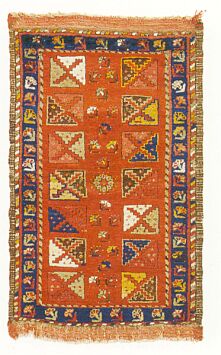

First, a classic example of how synthetic dyes can be used to brutalize the eye

in a woven good, and, an excellent reason to carp about synthetic dyes (plus,

this looks like it’s just WAITING to bleed all over the place when it

finally gets wet):

OUCH !, say my eyes !! But wait. Before we throw the baby

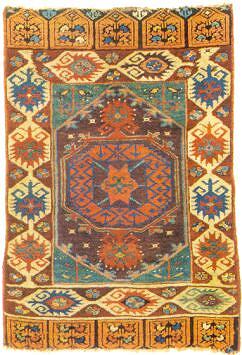

out with the bath water, lets look at the following examples, also produced

with synthetic dyes. But this time, in the hands of someone interested in

visual harmony:

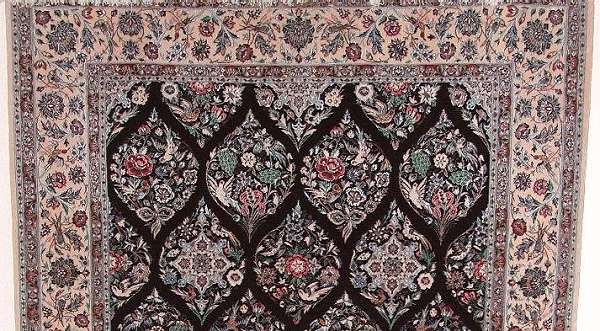

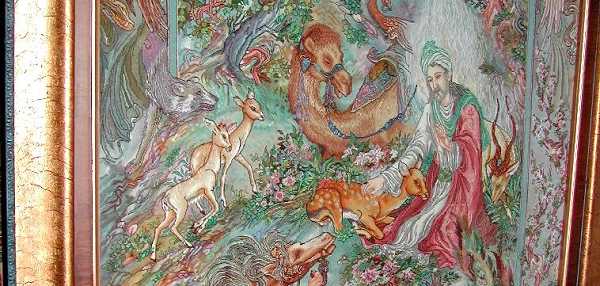

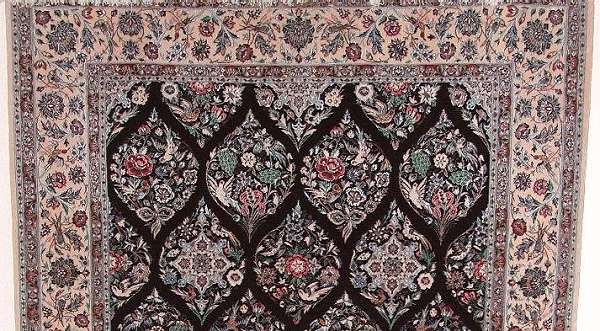

A framed Tabriz pictorial rug:

A border element from a Tabriz rug (there are more

shades in this little bit than there are in most carpets):

A modern Nain rug:

Note that none of the usual complaints about synthetic

dyes hold here. All have been exposed to light, none show any hint of bleeding,

and none exhibit the electric colors on the first image. So what do we say now

? Here is clear evidence that in the right hands, synthetic dyes perform as

well, or better, than the best natural dyes.

But wait Chuck: why, then,

don’t we see such delicate shades in tribal goods ? Economics. I think.

The number of shanks of yarn a weaver would have to keep in inventory in order

to produce colors like these is enormous. Few tribal weavers could afford to

buy and hold that much wool. And producing so many subtly different shades in a

rustic environment is not practical.

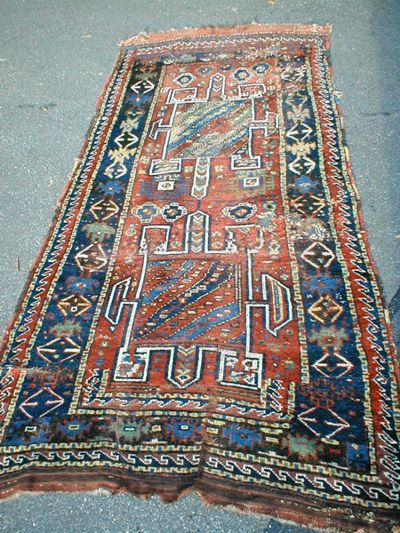

So, we see the transition from the

old to the new manifest itself in pretty unmistakeable ways. For starters,

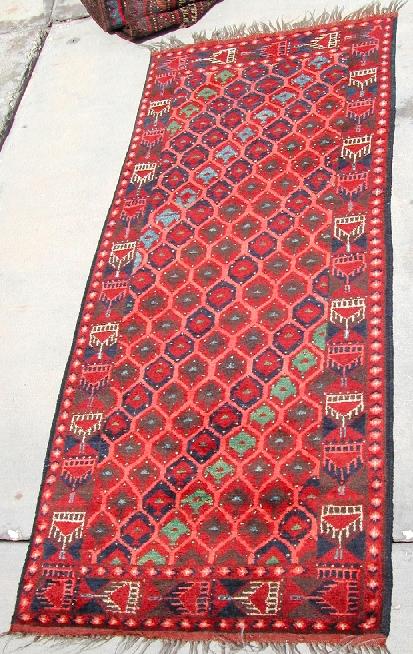

we’ll look at an old Baluchi bag, the type Ferrier described as being

capable of holding liquids without leaking. This thing is like a board, very

tightly constructed, and with traditional colors: