by R. John Howe

On September 22, 2007, John

Wertime conducted a rug morning program at The Textile Museum on the

subject “Sumak: the Very Collectible Bags from Northwest Iran and

the Transcaucasus.”

Here is an older photo of John, taken in 1997. It gives you a

more sober view, more appropriate to his scholarly identity and persona,

And provides a useful corrective and counterpoint to the jocular one

below that I took one recent Christmas at a party of ruggies.

John and I talked a bit beforehand about whether photography could be

permitted. He said that some of the pieces he would show were not

his and so that probably we should not take photos. So what

follows is doubly “virtual.” You are participating in

this rug morning via the internet and, although some of the pieces I

will show below are those shown by Wertime this morning, most are

not. What I can manage for you is to include published pieces of

all the geographic areas he treated.

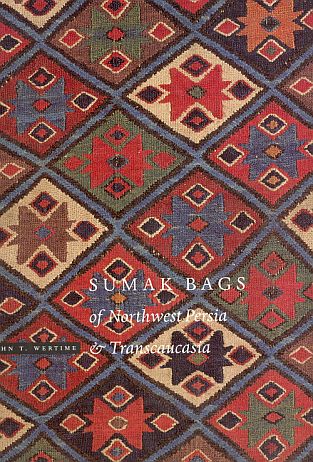

Wertime is an authority in this area. He lived nine years in Iran

as a young person, speaks Farsi and was a member of in early group of

rug scholars in Iran what included Parviz Tanavoli and, I think, Jenny

Housego. Wertime was in the Persian studies program at Princeton,

and has published several works in the area of his rug morning

topic. He authored an early article on flatwoven structures,

co-authored “Caucasian Covers and Carpets” with Richard

Wright, and more recently, published “Sumak Bags of Northwest

Persia and Transcaucasia,” a volume on which this rug morning was

explicitly based.

Wertime began with some general remarks.

He said that

we are disadvantaged in rug and textile studies by a paucity of

evidence. There are few instances in which we have direct

knowledge, for example, of where a piece was woven, or of who wove it;

what he and Wright called an “anchor piece.” For this

reason, he indicated, we are driven back to more indirect methods of

establishing such things as attribution and provenance.

Information from travelers, those who deal in textiles, and various

features of the weavings themselves, are the bases for what we, rather

insecurely, “know.” As a result, he said, smiling,

nearly everyone is “expert.”

Wertime said that the industrial revolution had an enormous impact on

the traditional production of textiles. He said that no activity

occupied more time in traditional society than did the production of

textiles. In traditional society most people, excepting the upper

levels of society, often had maybe one change of clothing. The

industrial revolution made the production of textiles much less

expensive and as a result, reduced their prestige markedly

.

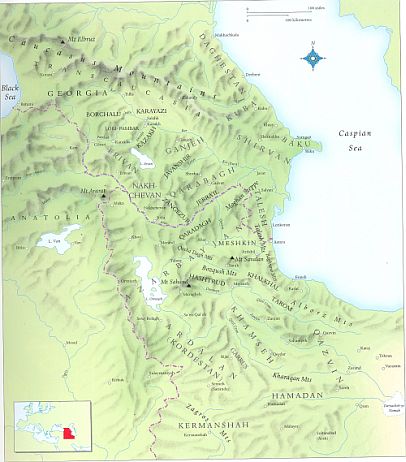

He said that the weavings of his subject were made by women in a

geographic area approximately reflected in this map. He would

move south to north.

He said that the southernmost region in which the weavings on which his

talk would focus, were made is defined by the areas of NW Iran named

Kamseh (not the South Persian Kamseh), Garrus, Qazvin, Saveh and

Kharaquan. On the west it bounded roughly by Anatolia and moving

north, encompasses the transCaucasus, including Georgia and Armenia.

Wertime noted that the weavings of interest in his session were woven

by women who husbanded both the animals from which the fibers (cotton

aside as plant-sourced), were taken and the plants used to make the

dyes. They also did the dyeing, the carding, the spinning, and

the weaving themselves. These bags were the result of what we

would today describe as a “vertically integrated”

production. There was little “division of labor.”

Next he talked about the character of “sumak.” He

said that “sumak” is a shorthand term for a weave in which the warps are wrapped with wefts. He distinguished it from

“tapestry” in which the warp and weft are

“inter-laced.” He held up a side panel of a cargo bag

from the Shirvan area made using slit tapestry and asked the audience

to note the holes visible in it.

Then he held up another panel made using “sumak” and asked

the audience to notice that there were no holes visible in the

resulting material. He said that tapestry weaving had been

mechanized but that “weft-wrapping” has, so far, not

been. Sumak is by its nature tied to and requires the use of a

more traditional mode of production and is, in that sense, likely more

closely reflective of that tradition.

He said that more sumak is woven in NW Persia and the transCaucasus

than anywhere else. He acknowledged that some is woven in eastern

and western Anatolia and in southern Iran but that it was rare in

Central Asia. He asked Kelly Webb and me whether either of us

knew of Central Asian uses of sumak. (The closest thing I could

think of quickly is the Turkmen palas, which have extra weft patterning

but not, I think, of the wrapped sort. I have also seen some

flatwoven Ersari khorjin, but don’t know what weave was used,

perhaps some sort of brocade. As I wrote today I found a

published item of Turkmen sumak, but I think it is a rarer thing.)

Wertime said that, in his view, the fact that more sumak was woven in

the NW Persia-transCaucasia area than anywhere else suggested that this

structure likely originated there. He said that he was following

a principle analogous to one in biology and botany under which species

are usually found to have originated near the area in which they occur

most frequently.

He next noted that the groups who wove these sumak bags moved

geographically. Some were nomads and moved following their herds

from season to season. Sometimes whole tribes were moved

considerable distances by government fiat. Third, Wertime said,

there seems to have been considerable intermarriage between groups in

this area, and often women moved from tribe to tribe, or sometimes some

distance, to marry. He said these various movements of people

helped explain both why and how different designs and techniques might

appear in different geographic areas. (The situation he described

seems contrasted with what is generally seen to be the predominant

pattern of marriage among, say, the Turkmen. The latter seem to

have tended to marry closely within tribal, even kinship groups.)

Wertime noted that flatwoven structures vary far more than do those

associated with pile weaving. And the color palette often

associated with flatweave, especially Shahsavan sumak, is considerably

wider than that of the most studied textile group, the Turkmen, where

there is rejoicing if more than five colors are found in a piece.

This variety makes textiles woven with sumak especially interesting

objects of textile collecting and research.

With these introductory remarks Wertime moved to the pieces he had

brought as well as to some others had. He said that he would

organize his progression geographically moving south to north.

The “southern region” as defined by Wertime, includes sumak bags woven in the Qazvin, Saveh and Kamseh areas.

Wertime said the southern-most Shahsavan in NW Persian in the

Qazin and Saveh areas are the Inallou and the Baghdadi. This end

panel below is from one of the oldest Baghdadi bags known and was shown

in this rug morning program. It is attributed to the Saveh

–Kharaqan area and estimated to have been woven in the 2nd or 3rd

quarter of the 19th century.

This example shares the heavy, stiff handle of some other Baghdadi

bags, as the result of wrapping two warps rather than one. They

are sometimes wrapped so that one warp is on top of the other.

The line of weft twining countered to form a chevron design at the top

of this piece, and the minor “connected buds” border, are

also characteristic of Baghadidi weaving.

Wertime said that as wefts are wrapped around warps they

“angle” in various degrees. Sometimes the wrapping in

each subsequent row continues so that the angle of the wrapping in a

given row parallels that of the row(s) next to it. But the

wrapping can also be made in a subsequent row so that it slants in an

opposite or “countering” angle. When the slant of the

wrapping alternates row to row, the sumac produced is described as of

the “countered” variety. This countering affects the

texture of the fabric, but is not reflected in its design.

Baghadadi sumak, Wertime said, is characteristically of the countered

sort.

In his book Wertime includes only one piece from the Saveh-Kharaqan

area, but the next 40 pieces are from the Kamseh area. So I am

going to have to be very selective about the latter. I’ll

show you four.

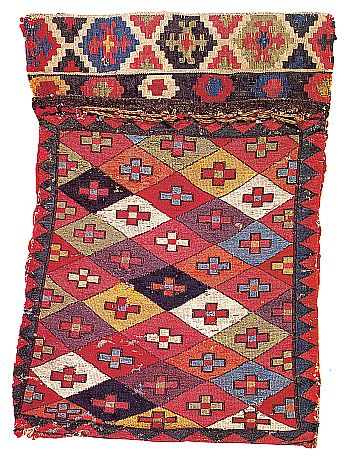

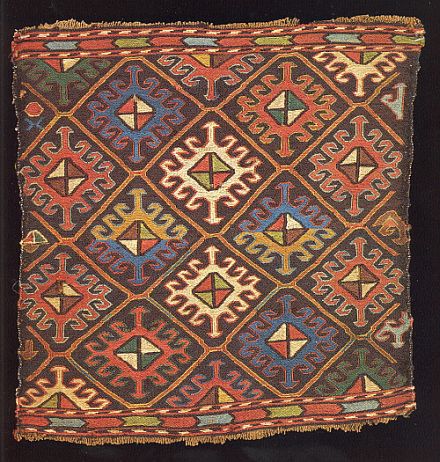

This is Plate 14 in Wertime’s “Sumak” volume and was not shown in this rug morning.

It is a side panel of a bedding bag from the Kamseh area.

Estimated to the 1st half of the 19th century. Notice that it has

a border all round. We’ll talk about that later.

I find its graphics and colors to be exceptional. Wertime says

this is a masterful use of this field design on a large scale.

Note the “bird-on-a-pole” main border is a version of one

that we see elsewhere, often on Yomut Turkmen “envelope”

style bags in pile.

The piece below is a second Kamseh area piece that is Plate 26 in

Wertime’s “Sumak” volume. It was not one of

those shown in this rug morning.

Wertime describes this as a “masterpiece of design and

color”…with its “…five complete and two half

Lesghi stars…” He notes that in some pieces the

stars are arranged are aligned vertically with one another. I

think the dark outlining around them is especially effective.

The piece below is a third Kamseh area piece.

As you can see, it is a complete khorjin set, estimated to have been

woven during the 3rd quarter of the 19th century. Wertime says

that it displays a distinctive Kamseh palette. He also says that

the border above the closure panel is “infrequent.”

I find it a little crowded and busy, but agree that its colors are glorious.

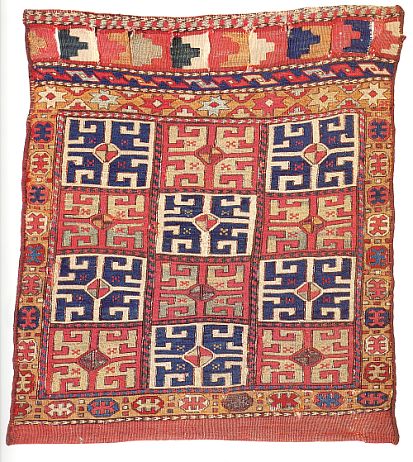

The saddle bag face below is a fourth Kamseh example (Plate 39 in his

book) and was not among those shown in Wertime’s rug

morning.

He says that use of the device in the field compartments of this piece

is “widespread and ancient,” and quotes sources suggesting

similar usages in 14th and 15th century Anatolian fragments.

Wertime notes this design also occurs in Uzbek weaving. He

estimates that this piece was woven in the 1st quarter of the 19th

century.

I am a sucker for compartmented designs and am very attracted to the

large scale of the field motif. I also like the fact that the

border does not compete with the field, nor does the larger scale

design on the closure panel, the latter, perhaps because it is still

somewhat smaller and different from the device used in the field.

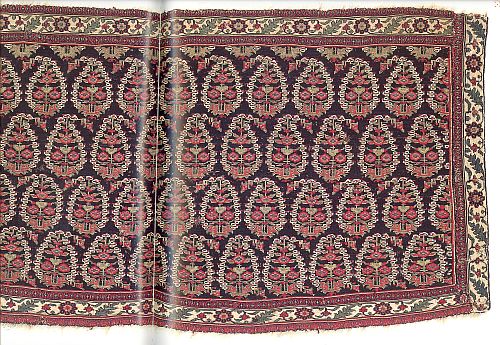

The third geographic area Wertime treated in this rug morning was

“Garrus” (most of us think “Bidjar” when we

hear “Garrus”) and his Garrus example is a repeatedly

published and widely praised one. Wertime included it among his

rug morning pieces and it is Plate 42 in his book. It is a side

panel of a bedding bag with a border all round. It is treated

there in a two-facing-page spread so I can’t scan it all

successfully, but here is the detail of it that I can manage.

Wertime describes it as very fine and very old, estimating it to the

1st half of the 19th century. He also notes that the border on

the right side is not original and was “most likely) taken from a

similar panel on the other side.

At this point Wertime talked a little about the seeming use of design

in complete bedding bags of this type. In general, it seems that

if the side panel design does not have borders all around it, the

design on the side panel is carried all the way around in the other

side panel and both end panels.

Here, below, is an image of a complete bag of this sort from the

Azadi-Andrews volume “Mafrash” that shows the side panel

design continuing all round the other four panels.

But, in the case of a side panel with a border all round, usually, the

other three panels will be different from it. The way in which

this difference can occur can apparently vary, but here below is

another complete bedding bag from the Azadi-Andrews book that shows one

side panel with borders all round it and the other three sides in a

zigzag design.

If the right side border on the Garrus piece above comes from a

matching side panel on its opposite side that would seem to be a rare

occurrence, although the right side border is so similar to that on the

rest of this panel that that explanation seems plausible.

The next next geographic area that Wertime treated in his rug morning

program was that of Hashtrud-Miyaneh. The piece below is Plate 52

in Wertime’s “Sumak” book but was not one of those

shown in this rug morning.

On the other hand several pieces from this area and with this design were shown.

Wertime indicated that this is another form of sumak in which there is

90 percent displacement of every other warp in the wrapping.

Another, even more unusual feature, he said, was that this piece is

made with an “extra-weft wrapping” structure in which

“a true knot if formed in the wrapping process.”

Wertime used the example of the knot one uses to tie one’s shoes,

but I think what he intends is that a lot of “knots” in the

world of textiles are not “true knots” in the sense that

they are not “firm on the basis of their own

construction.”

(Both symmetric and especially asymmetric knots in pile weaving do not

meet this test fully and require “pinching” by the wefts

between knot rows in order to remain firm. The asymmetric knot is

in fact closer to what might be better described as an “in

lay” in this respect. The symmetric knot is

“firm” as long as tension it maintained on its cut pile

ends. Otherwise, it too, is dependent on the pinching wefts to

retain its firmness.)

I think Wertime is suggesting that this extra-weft version of sumak is

one in which the knots are firm on the basis of their own

construction. That is, I think, a fairly unusual occurrence in

the weaving world.

Wertime also used this khorjin set to reinforce the point that in

general designs seem to move from techniques that are more restrictive

to those that are less so. Sumak, like pile weaving, is one of

the less restrictive techniques. Nearly any design can be

executed on it since its minimum requirement is only that one

patterning weft must circle one structural warp. Wertime brought

out the example of zili shown below, a species of brocade and a more

restrictive technique.

Notice that this zili has this same design.

Wertime said that he felt that this design likely flowed from pieces

made in more restrictive techniques, like the zili, to those made with

less restrictive ones like the sumak.

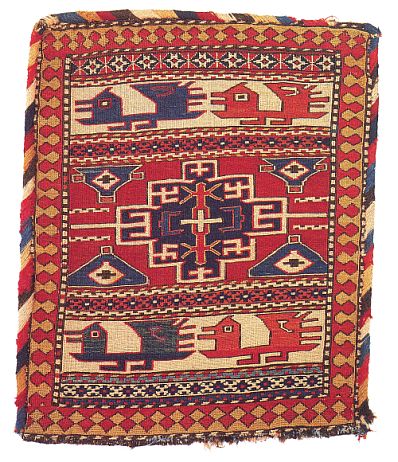

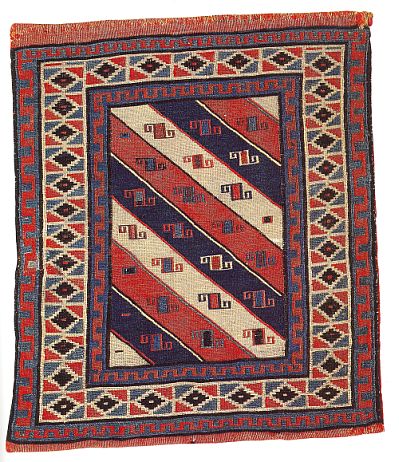

A second piece from the Hashtrud-Miyaneh area is the saddle bag half below.

It was in the room for this rug morning and is dated 2nd quarter 19th century.

Wertime said that the provenance of this piece is

“problematical” and that its attribution is based in part

of the fact that it has warps on two levels. He says that the

central medallion is “rare” and that the birds are drawn

somewhat differently than most in this area. It is Plate 55 in

Wertime’s book. Plate 56 is a very similar piece.

The next geographic area Wertime illustrated was Moghan-Savalan.

He had the piece below in the room (it is Plate 73 in his book) and

explained why he had included it rather than the more striking piece

(Plate 74) that Wendel Swan owns.

He said that he estimates that this piece is older than Wendel’s

piece (he says 1st quarter, 19th century and estimates Wendel’s

piece as 3rd quarter) and says that it has a lighter purple or violet

in its corners that is derived from madder. He says that dye is

common in Anatolian pieces, but rare in those made by the

Shahsavan. The piece shown lacks the exquisite condition and the

saturated colors of the Swan piece, but its fragmentary dark-ground

border with stars and cruciform devices still effectively frames the

milder field this old weaving.

A second piece from the Moghan-Savalan area is the one immediately below.

This piece was not in the room on this rug morning, but is one of the

most beautiful weavings of which I know, so I’m giving it to you

from Plate 87 in Wertime’s book.

There he says that it is “a marvel of colour and elegant

simplicity.” He attributes this to use of a somewhat larger

scale and a spaciousness created by refraining from making the

cruciform devices larger. He sees it as a “stunning display

of the dyer’s art” and especially admires its purple.

Wertime also explicitly admires the simple borders and the

“elaborately decorated bridge in slit tapestry.”

It is estimated to have been woven in the 1st quarter of the 19th century.

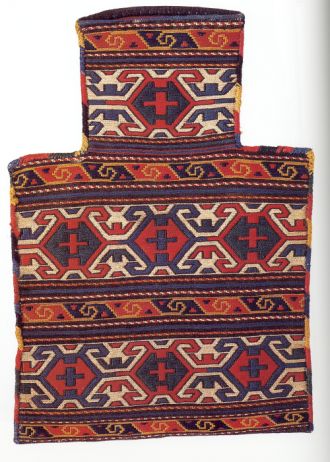

Wertime showed several smaller bags and the one immediately below,

about 10 inches square, may not have been among those shown, but is

similar in coloration and design to one that was.

Wertime also attributes this piece to the Moghan-Savalan area,

describes it as a “small saddlebag” and estimates that it

was woven in the 2nd half of the 19th century. He notes that the

ground weave of this piece is warp-faced. He noted that these are

often seen as children’s items but said that they are made at a

level of quality that makes this doubtful.

Wertime next moved to items from the Kuba area. The piece below

is a saddlebag “half” and is estimated to the 1st half of

the 19th century.

Face to face this piece draws immediate attention as an older and likely sophisticated piece of work.

Wertime’s next example, below, comes from Qarabagh.

It is a salt bag, estimated to have been woven in the last quarter of the 19th century.

Wertime calls it “beautiful” and cites its wonderful

graphics. It was not in the room for his rug morning, but appears

as Plate 117 in his book.

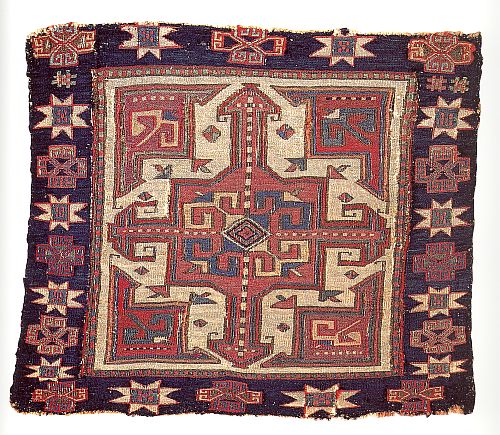

Wertime describes the next saddlebag half, below, also from Qarabagh as

“one of the greatest sumak bags known.”

He says that is proportions are “optimal” and praises its

“simplicity” and “grandeur.” It has the

sort of spacious drawing that might draw even a determined Turkmen

collector to a Caucasian weaving. We were not fortunate enough to

have it in the room. You need to go to his volume and read more of his

fulsome praise for this piece.

In Wertime’s book, his next geographic area is Kazkh and he offers the salt bag below (Plate 133) as one such example.

The good, strong colors of this piece are appealing and its graphics

are striking. Here is a little of what Wertime says about it in

his book.

“An attractive feature of this bag is the three-dimensional

effect created by the device that fills the hexagonal centres of the

repeating motif of the ivory bands. The middle of this device

appears as a negative cruciform that pulls the viewer into another

realm.”

Another piece from the Kazakh area was in the room. It is a side

panel of a bedding bag and is Plate 134 in Wertime’s sumak book,

estimated to have been woven 3rd quarter 19th century.

The field design is very unusual and one of the owners of the piece

said that they especially like the “ducks” swimming about

in the lower half of the field devices, something that Wertime notes

specifically in his description of it. Wertime says that this

treatment of the blue-ground border is rare because it occurs on the

sides not just top and bottom.

This is a piece that draws the eye face to face. I think the use of white especially effective.

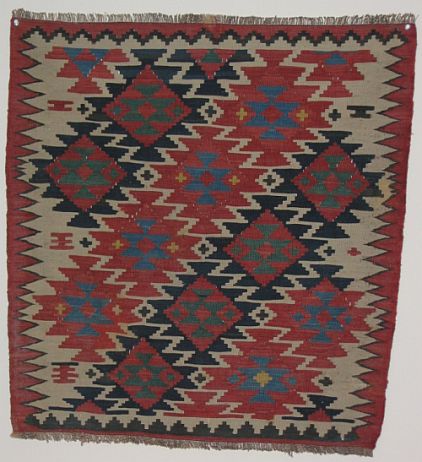

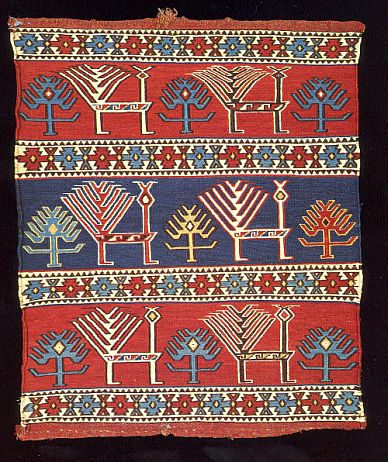

At the end of his book, Wertime treats Kurdish pieces separately.

The piece below is Plate 136 and is a complete Kurdish khorjin

set. It is attributed to Northwest Persia and is estimated to

have been woven in the last quarter of the 19th century. We did

not have this piece in the room in this rug morning but did have a

Kurdish chuval that was quite similar.

Wertime says that the field design is a Turkic one used by weavers in a

number of locations. He says that it is similar to weavings in

the Kamseh confederacy excepting that it has “a different

palette, its pile bottom (I had forgotten in our recent discussion here

that pile bottoms can occur on Kurdish pieces), its use of two ground

wefts after each row of wrappings and its frame, particularly the guard

stripes. He makes comparisons with a piece that Housego discusses,

her Plate 40, and that Wertime examined directly years ago.

Wertime’s discussion of this piece focuses largely on it

attribution.

I want also to show you two pieces from the area of Wertime’s rug

morning, but from the Azadi-Andrews book “Mafrash.”

Both of these pieces are end panels from the sort of bedding bags we

have been treating.

The first is this powerfully graphic piece below.

It is on page 121 and is described as Shahsavan “North of the River Aras, third quarter.

I find its graphics breathtaking. We had a similar piece in the room in Wertime’s session.

A second end panel is more sober.

It is on page 123 and is described as “Shahsavan” from “Northwest Iran, mid-XIXth century.”

I like the use of a dark ground and of the color choices and outlining

on the hooked lozenges that let them stand out from it.

Azadi-Andrews also draw attention to the simplicity of the

“triple horizontal border.”

That is what I have to show you of sumac bags from northwest Persian and the transCaucasus.

This was an excellent rug morning of the more authoritative type.

Our thanks to John Wertime for conducting it.

Regards,

R. John Howe