Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-10-2007 02:52 PM:

Warps on two levels

Hello John and all,

Part of John Wertime’s Rug and Textile

Appreciation Morning program at the TM explored the question of whether

structures in certain rare sumak weavings can assist in identifying provenance.

In particular, Wertime focused on several bags with “warps on two levels” (his

term) or “fully depressed warps” (another term sometimes used by

others).

We’re all familiar with fully depressed (i. e., 90 degrees)

warps in many pile Persian city rugs such as Saruks and Kashans, but the

phenomenon in flat weaves has not been much discussed.

As with pile rugs,

having warps on two levels in sumak bags produces a thick, heavy, leather-like,

firm handle that would be very durable. The thicker the warps themselves, the

“thicker” the handle.

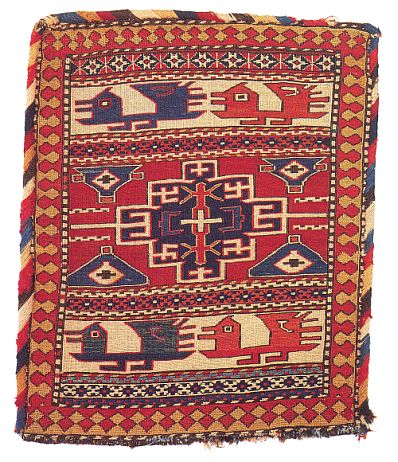

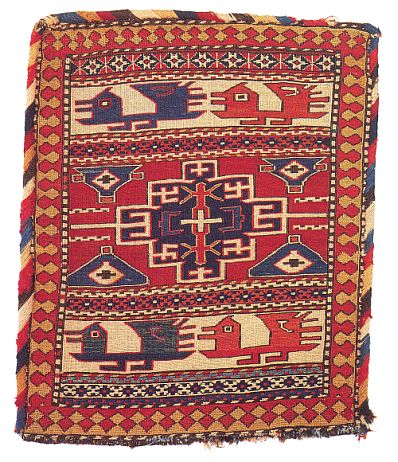

This Baghdadi Shahsavan (southernmost of the

Shahsavan groups) mafrash end panel was plate #1 in Wertime’s Sumak book and has

the characteristic “thick” handle. This panel has warps of brown and ivory yarns

twisted together, some cotton in the warps and the wrapping wefts, some

countering of the weft wrapping and twining at the top and bottom.

Although in Sumak he

attributed this mafrash side panel to the Kazak area of the Caucasus, Wertime

now wonders whether it should be grouped with the Baghdadi end panel on the

basis of the thick handle and the presence of twining – something not normally

encountered with sumak.

Several other sumak weavings with thick handles and depressed warps

were brought in to the program. This is one of mine that Wertime also believes

may be Baghdadi:

This well-known khorjin half also has depressed warps and a thick

handle.

The use of

warps on two levels must have been developed in order to make very durable

utilitarian weavings.

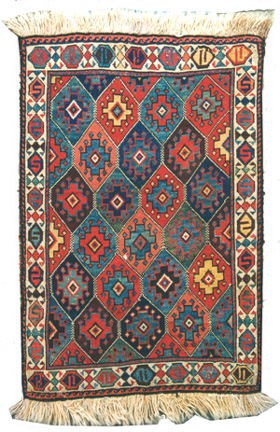

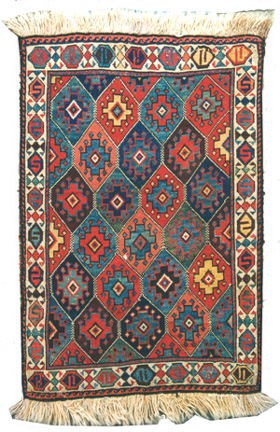

The audience must have brought in seven or more

reverse sumak pieces with Zili designs such as this one of mine:

Because of different colors,

materials and designs, we could easily believe that putting warps on two levels

is a relatively widespread practice in NWP. However, Wertime is currently

exploring whether there is a primary connection to the Baghdadi

Shahsavan.

All of the pieces shown above were shown at the program and

there were many, many more excellent examples of sumak weaving. These RTAMs at

The Textile Museum provide an outstanding learning experience.

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-10-2007 05:23 PM:

Wendel -

Say a little about how the depression of alternative warps in

these sumak pieces is accomplished.

In pile weaving, it seems to be

accomplished by making at least one set of structural wefts taut and/or by

"crowding" the number of warps in a given width.

Is it the same in sumak?

I assume that any sumak with deeply depressed alternate warps has a structural

set of warps and wefts and that the patterning wefts (the ones that wrap) are

separate from them. Correct?

Thanks,

R. John Howe

Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-11-2007 11:29 AM:

Hi John,

You posted:

quote:

Wendel -

Say a little about how the depression of alternative warps

in these sumak pieces is accomplished.

What I could say of my own knowledge and experience would be

very little indeed.

In her book, Marla Mallett says: “This warp

depression is made possible and orderly solely by the way weft yarns are

inserted. Alternating wefts are allowed different amounts of ease.”

I

don’t know the hand movements in weaving either sumak or pile with depressed

warps, but it may be that the weave pulls harder on one end of the yarn when

either creating the “knot” or performing the wrapping when depressed warps are

planned. In any event, as Marla indicates, the wefts alternate between being

sinuous and straight.

You also posted:

quote:

In pile weaving, it seems to be accomplished by making at least one set of

structural wefts taut and/or by "crowding" the number of warps in a given

width.

It seems obvious that a weaver must set up the loom and the

warps specifically for the degree, if any, of depression of the warps. When the

warps are on two levels (90 degrees of depression), there are twice as many

warps per linear inch horizontally as when there is no depression. The warps

would have to be as close to one another as possible. The weaving cannot pinch

or “crowd” the warps; the weaving comes off the loom the same width as the warps

were set up initially.

You also posted:

quote:

Is it the same in sumak? I assume that any sumak with deeply depressed

alternate warps has a structural set of warps and wefts and that the

patterning wefts (the ones that wrap) are separate from them. Correct?

I brought in to the session an example of what can be called

simple sumak wrapping or weftless sumak, a weave not found very much outside

Eastern Anatolia. Here, there are no structural or ground wefts, only patterning

wefts. The result is a very supple weaving where gaps between colors can be

readily seen. In terms of handle and durability, it is the polar opposite of

sumak wrapping with depressed warps.

Otherwise, sumak wrapping has

structural or ground wefts, just as does pile weaving. John Wertime would

contend that conceptually there is not a great deal of difference between pile

and sumak wrapping except that the wrapping wefts are cut in the case of

pile.

There was a reference to "knotted reverse sumak", which is a

somewhat sturdier weave than reverse sumak. We know that the “knots” in pile

carpets are not true knots. One could engage in a broad discussion of knot

theory, but Marla Mallett illustrates knotted reverse sumak (illustration 5.25

is a khorjin face of mine) as being like a clove hitch.

What is a knot?

Some would argue that to create a knot the yarn must encircle itself or not

collapse when the object to which it is tied (in our case the warp) is removed.

The simplest knot is an overhand knot. If you want to see a clove hitch, go here

and ponder where a clove hitch is a true knot:

http://www.realknots.com/knots/hitches.htm

There are

many, many variations of sumak wrapping. In John Wertime's session alone, we

probably saw four variations of sumak wrapping on depressed warps. Depending on

how finely we draw distinctions, there are surely many more.

Sumak

wrapping is a sophisticated and versatile technique.

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2007 01:16 PM:

Hi Wendel -

What you have written above is useful.

First you

confirm my understanding that sumak with fully depressed warps cannot be

"weft-less sumak."

You wrote in this context:

"...sumak wrapping

has structural or ground wefts, just as does pile weaving. John Wertime would

contend that conceptually there is not a great deal of difference between pile

and sumak wrapping except that the wrapping wefts are cut in the case of

pile."

Me: So I think your answer to my question is "yes."

You

also talk about depressed warps and how that is accomplished. Here you say in

part:

"...It seems obvious that a weaver must set up the loom and the

warps specifically for the degree, if any, of depression of the warps. When the

warps are on two levels (90 degrees of depression), there are twice as many

warps per linear inch horizontally as when there is no depression. The warps

would have to be as close to one another as possible. The weaving cannot pinch

or “crowd” the warps; the weaving comes off the loom the same width as the warps

were set up initially..."

Me: It is true that the number of warps

included in the orginal set up of a given weaving on a loom contributes to

whether warps will be depressed or not. The word "crowded" actually comes from

Marla and refers to a situation in which the combined width of warps planned to

be included is higher than the available horizontal distance in the planned

width of the weaving. Such crowding makes it necessary that all the warps to be

included cannot be on the same level.

So there will be some depression

occasioned by this "crowding," but there is another variable of concern, namely

the "order" of depression.

Since what is desired, usually, is that only

alternate warps be depressed, the weft also plays a role in this depression by

defining the order and frequency of warp depression. And, of course, if this

"depression-defining" weft is also taut, it can contribute to the depression

itself as well.

(Note: I would not argue that there are not sometimes

instances of full depression of alternative warps that are mostly a function of

taunt wefts, only that if there is "crowding" the crowding contributes to the

depression.)

Third, you raise the issue of "What qualifies as a knot?"

This is an arena in which my macrame experience, and my related contact with

nautical knotting, applies. It is not importantly germane to our consideration

of sumak structures, but may still be useful to review.

First, the word

"knot" is ambiguous in the various literatures in which it is used. Some usages

are not demanding at all. Referring to the useful link you provide a "simple

hitch" is not very firm at all.

http://www.realknots.com/knots/hitches.htm

But at the

other end of the continuum of knot structures that some argue the term "knot"

should be restricted to, we have knots that are "firm on the basis of their own

construction."

A "square knot": two overhand knot tied one on top of the

other in the manner shown in the drawing in this link is one of the simpler

knots that is firm on the basis of its own construction.

http://www.inquiry.net/outdoor/skills/b-p/knots.htm

In

pile weaving, the asymmetric knot does not meet this latter requirement at all

since it is composed of a "simple hitch" around one warp and an "inlay" on an

adjoining one. The firmness of asymmetric knot is entirely dependent on the

pinching action of the wefts above and below it.

The symmetric knot is

closer to a knot that is firm on the basis of its own construction but still

requires constant tension on its "pile" ends (which are cut off as the weaving

proceeds) for its firmness. For this reason, it too is dependent to an extent on

the pinching actions of the wefts above and below it for its firmness.

I

got a small credit from Marla Mallett in her first edition for raising and

arguing this issue with her before publication. He husband asked to be

introduced to the person who had made so much trouble about the word "knot."

I'm a bit off topic

with this latter dissertation on "What is a knot?", but I think your comments

clarify most of the issues in my previous question.

Regards,

R.

John Howe

Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-11-2007 03:00 PM:

Hi John,

I also don't want to deviate too much on the topic of knots,

but the subject is interesting. You said:

quote:

The symmetric knot is closer to a knot that is firm on the basis of its own

construction but still requires constant tension on its "pile" ends (which are

cut off as the weaving proceeds) for its firmness.

Is "closer to a knot" something like being closer to

pregnant?

Anyone who would consider a half hitch to be a knot would also

consider a symmetric "knot" to be a knot. I don't. I prefer the more restrictive

definition you cited that knots must be "firm on the basis of their own

construction."

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2007 03:47 PM:

Wendel -

As I said, the word "knot" is ambiguous, in part because it

has been used historically to refer to different structures.

And there is

an associated debate about what range of structures should be referred to with

the word "knot."

So it's not (sorry) a question of being a little bit

"pregnant" since what counts as a "knot" is not an "either-or" thing, but rather

a continuum about which folks disagree about the applicable portion.

To

show how stern some "knotters" can be, some naval knotters do not consider the

"square knot" example I offered to be a "firm" knot since under sufficient

tension it can change structure and slip. Here's link that makes this

argument.

http://www.42brghtn.mistral.co.uk/knots/42ktreef.html

You

need to be careful getting interested in "knotting." It's a field like rug

collection that can consume you. Here are a few links in warning:

Here

are some serious "knotters."

http://www.igkt.net/

But if you're not (again, sorry)

careful you can find youself in a field of mathematics.

http://www.ccs3.lanl.gov/mega-math/workbk/knot/knot.html

http://www.popmath.org.uk/exhib/knotexhib.html

http://mathforum.org/library/topics/knot_theory/

If you

venture into any of the mathematical knot theory sites you'll find that neither

the symmetric nor the asymmetric knots can qualify as mathematical knots because

the latter are restricted to structures that have no loose or dangling

ends.

Aren't you sorry you went on about this?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-11-2007 04:54 PM:

Hi John,

Perhaps I will regret the foray into knots, but I was the one

who first something that I really don’t know very well: knot theory. I’ve

already spent entirely too much time browsing through some of your fascinating

links.

Some of the sites are relevant to rug studies. One site has

several versions of the Celtic knot, which is essentially the same creature as

the Holbein interlace. There is a relationship between knot theory, principles

of symmetry and that considerable portion of Islamic art that is based upon

mathematics.

I have no training in mathematics myself. I’m generally much

more concerned with aesthetics than ethnographic significance. Viewing textiles

in a mathematical context may seem cold and distant, but I think doing so is far

more productive to rug and textile appreciation that pondering the “meaning” in

them.

Now, isn't anyone intrigued by the fact that sumak wrapping is

sometimes done with warps on two levels? Or is that just too

arcane?

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2007 05:46 PM:

Wendel -

There was one place where Wertime was talking about sumak

with warps on two levels where he said that this "extra weft wrapping" structure

was on in which actual knots were formed.

The pieces in question, I

think, were those from the Hashtrud-Miyaneh area.

In my virtual treatment

of this part of his presentation I used the piece below.

As I indicated in my reporting

this piece was not in the room but there were maybe five of this type brought

in.

Here is what I reported about them in my virtual telling of Wertime's

lecture.

"...Wertime indicated that this is another form of sumak in

which there is 90 percent displacement of every other warp in the wrapping.

Another, even more unusual feature, he said, was that this piece is made with

an “extra-weft wrapping” structure in which “a true knot if formed in the

wrapping process.” Wertime used the example of the knot one uses to tie

one’s shoes, but I think what he intends is that a lot of “knots” in the world

of textiles are not “true knots” in the sense that they are not “firm on the

basis of their own construction.”

(Ed.: My italics added here)

I

am not sure what this "true knot" structure looks like.

Wendel, maybe you

could ask him whether there is a drawing of it anywhere. Or do you know

yourself?

This is a place where our discussion of "knots" intersects

precisely with Wertime's session.

I think the occurence of what we might

call a "true knot," that is, one that is "firm on the basis of its own

construction" is a relatively rare thing in the weaving

world.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Wendel Swan on 10-11-2007 06:16 PM:

John,

The Chapman bags have truly glorious colors. Too bad we didn't

see them that day.

I posted a discussion of knotted reverse sumak earlier

in this thread, wherein I said that this kind of wrapping is like a clove hitch,

based upon Marla Mallett's illustrations. I would not call a clove hitch a true

knot in that it would collapse if the warps were removed. It is not firm in its

own construction.

See illustration 5.25 in Marla's book for an image of

the reverse side of one of these. That one is mine.

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 10-11-2007 08:17 PM:

Wendel -

"Clove hitch" is good. I missed it somehow in your previous

post.

I have only Marla's first edition which does not have a 5.25

illustration. That must be one of the changes made in her second

edition.

Here is another image of a "clove hitch" for others who might

have missed it above.

http://www.instructables.com/id/Tieing-a-Clove-Hitch/

If

you rotated this image 90 degrees so that the wooden rod becomes the warp, that

is the structure that Wertime is apparently referring

to.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Richard Larkin on 10-12-2007 07:45 AM:

Hi John and Wendel,

I agree with John that the question, "to be or

knot to be" is properly answered in the context of a continuum. One can argue

about where on the continuum the answer is found. It is precisely not analogous

to the question of pregnancy. I also agree that as to pile weaving, the

symmetrical "knot" is fundamentally "firmer" than the asymmetrical knot. I

wonder whether this makes the symmetrically knotted fabric appreciably more

stable or durable than the other. It may be a question for physicists.

I

find the following comment attributed to Marla Mallett to be very

interesting:

“This warp depression is made possible and orderly solely by

the way weft yarns are inserted. Alternating wefts are allowed different amounts

of ease.”

If I understand this correctly, she means that the weaver

chooses and controls the phenomenon by application of technique. It seems

remarkable that such uniform and stable fabrics can be produced in this manner.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Steve Price on 10-12-2007 07:58 AM:

Hi Rich

That's exactly how warp depression is done in pile weavings as

well. One weft shoot is a little slack ("sinuous") so it more or less

half-encircles each warp, the next weft is taut, putting alternate warps into

different planes.

Clever people, these

weavers.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Marty Grove on 10-12-2007 08:27 AM:

Bi level

G'day John and Wendel,

Assuredly there are some of us who are

interested in these soumac weaving structures made on two levels - though I must

admit to knot (sri) not having the faintest clue just how it is done.

If

the design is created by wrapping threads around warps/1/2 or more, and the

structure is stiffened by having one warp below the level of that beside it, and

around these warps threads are wrapped, not individually on each warp

separately, but threads which are wrapped around one, then around the next etc

etc, and after all this, one of the warps in sequence must be below the other to

be able to call the structure 'depressed warps', well then I find it extemely

difficulty to visualise...

About the description 'knot' in rug weaving - Mumford refers to

them as 'stitches', and he is not the only old writer who does - any idea just

when stitches became knots?

Mumford also refers to Soumack, and an early

mistake in 'Soumack' supposedly being a khanate in Northern Iran/Caucasus rather

than a weaving 'type', which incorrect identification/provenance he made, and

which in books by others thereafter, the mistake was perpetuated until he

corrected it.

Apparently, in the earliest days of commercialism in rugs,

the soumac type of rug was given the appelation of 'Kashmir', this being a tick

of super quality, as the Kashmir shawls were considered the finest woven product

of the time - so sayeth Mumford.

Regards,

Marty.

Posted by Richard Larkin on 10-12-2007 06:12 PM:

Oops!

Hi Steve,

Once again, you've set me straight. In reading Marla's

comment, I was considering that the wefts dictating the depressed/two level

structure were individual supplementary wefts that also formed the surface,

giving the piece color and pattern. To apply these in a manner to dictate as

well the character of the fabric as a whole would be truly astonishing. I

realize, however, that it is the continuous wefts that are alternately slack and

taut, thereby setting up the two level situation. As that funny lady used to say

on TV, "Nevermind!"

__________________

Rich

Larkin