Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-17-2006 08:06 AM:

A Splendid Rug

Hi all,

Before we are completely wrapped up in Christmas preparations,

would you like to take a closer look at Cat. 4 with me?

This is the

unique 16th century triple medallion rug from Anatolia in the Black Church,

Brashov, 148 x 202 cm, 1300 kpsdm, on which Christine Klose focussed in her

presentation, and which Alberto Boralevi ‘looking mainly to the colours’

attributed to the Karapinar area in Central Anatolia. Also, as it said in the

handout to his presentation, this is probably the ‘most intriguing and most

interesting piece in the whole collection.’

Apparently, the rug

has in the past been widely discussed by several authors (Jon Thompson 1980,

Christine Klose and Ali Riza Tuna at 6th ICOC Hamburg). ‘All of them have

noticed the resemblance between the pattern of this piece and that of classical

Turkmen carpets.’ This is how Christine Klose acquainted us with this

perspective:

The image shows an endless repeat pattern familiar from

classical Turkoman rugs; varying the field-sector allows for design alternatives

that look astonishingly different:

In the case of ‘our’

rug three cruciforms on the same axis appear to have sintered into one body,

flanked by two half-göls and two quarter-göls on either side. What appears as

being unique to us, actually may have been not quite as much out of the ordinary

in the 16th century.

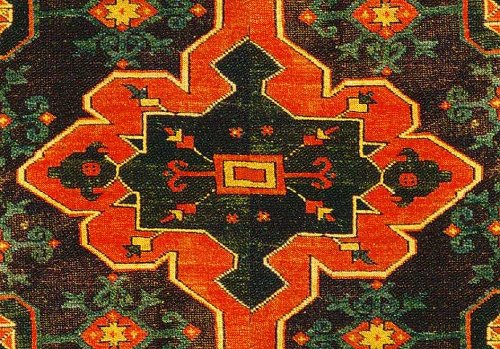

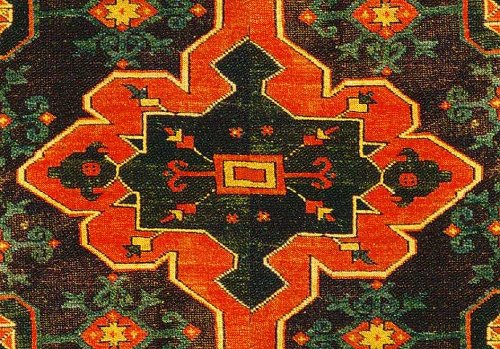

I am indebted to Christine Klose for providing the

following image in the course of the preparation of this essay. It shows rug

A-28 of the Vakiflar Museum Istanbul; judged by its appearance, from

east-central or eastern Anatolia and perhaps a contemporary of CAT. 4 – with a

size of 380 x 210 cm a rather large rug. Especially noteworthy is the similarity

of the cruciforms in the two rugs, an observation on which Christine Klose built

her Timurid tradition hypothesis.

A number of other

interesting thoughts and images in this context provides Dennis Dodds (1986 ?)

Truly Classical. Hali 39, pp 17-22, when he discusses the connection between

East Mediterranean designs of the Classical period and early Anatolian rugs with

reference to a fragment of a Sivas area weaving in the Bertram Frauenknecht New

York exhibition:

‘While much is known about the westward migrations of

Turkic peoples and their contributions to the design vocabulary of the weaving

cultures that they influenced, the role of the entrenched, resident cultures who

were dominated by the Turks and by Islamic people in general is less frequently

discussed. When observing form and style in the art of this region, it is

particularly important to understand that Islam borrowed frequently and

enthusiastically from the decorative conventions of existing local cultures.’

This about hits the nail on the head is the background against which

CAT. 4 should be evaluated.

Whilst the triple medallion forms a rather

imposing figure, there is another more elusive cruciform contained in the border

of the rug, under what appears to be gables forming an integrated part of

reciprocal trefoils, perhaps an early and sophisticated medachyl form. The

repeated cruciform in the border is tiny, only a few knots and one weaving line

wide on both axes:

It is difficult to say, what its significance is. At first

sight I thought of anchors, what doesn’t seem to make much sense – perhaps an

anther with petal and calyx? A similar motive appears on the 16th century Sivas

area pile rug fragment discussed in the Dennis Dodds article, and maybe does so

as part of various renditions of the tauk noshka and other Tukoman göls (as a

border design see plate 201, a Tekke torba, in Eiland and Eiland (1998) Oriental

Carpets. Page 230. In the same book, also highly interesting in this context,

plate 186, an early Turkoman rug with design features that link it to north-west

Persia, according to the authors.

The following image is derived at by

processing the half-göl forms of Cat. 4. The result looks all the more like the

central göl in Vakiflar A-28:

Until the

middle of the 20th century rugs with large central medallions that can be

regarded as being related to ‘our’ göl have been produced in an area described

as the ‘Yörük Triangle’ – Yohe R S (1979) Rugs of the Yörük Triangle. Hali II/2,

pp 113-120; Görgünay N (1971) Doguyöresi Halelari. Türkiye Is Bankasi Kültür

Yayinlari, Sanat Dizisi23, Ankara.

This is how Ralph Yohe defines the

‘Yörük Triangle’: Look at a map of Turkey. Draw a line from somewhere north of

Tokat (northeast of Sivas (more precisely, Tokat is situated north-northwest of

Sivas, H.N.)) eastward just north of Erzurum to somewhere between Agri and Kars.

Then trace it southwesterly to Diyarbakir, Gaziantep and Adana. Extend the line

northward, just missing Kayseri to the west, back to the spot where you

begun.”

The population, now mainly sedentary and assimilated to various

degrees, has origins in a variety of ethnic groups, Kurds, Turkomans, Tatars,

Afshari, Circassians, Armenians etc.

Could it be possible to link Cat. 4 to

any of them?

(To be continued)

Regards,

Horst Nitz

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 12-17-2006 12:48 PM:

More splendid still?

Thank you, Horst, for your closer look. Here's another one.

Please

look at the "quarter-gols" in the splendid rug's field corners. In each corner

is the silhouette of a red-eyed fetal dragon, isn't there? Has anyone spoken to

that? Sue

Posted by Richard Larkin on 12-17-2006 01:16 PM:

Hi Horst,

This is wondersul stuff. More! More!

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 12-17-2006 10:01 PM:

Cousins?

Horst,

The rug you show as A-28 from the Vakiflar Museum has a very

familiar gul in the center. It is quite a lot like a common Khamseh Basiri

design. A version of it can be seen on a bag face in this early Salon, just

below the Baluch balishts, picture number 7:

http://www.turkotek.com/salon_00045/salon.html

A-28 has

a quartered center, but this Khamseh type is found with a plethora of central

designs, from the ubiquitous "endless knot" in the pictured Khamseh bag to a

variety of floral and geometric motifs.

The Khamseh Basiri are a mixed tribe

with some Turkic origins.

If I were to see a rug like this from the 19th

century, though, I would say it looks more like Afshar weaving, with the rather

wider size and particularly the diagonal border. I wonder if A-28 has depressed

warps like Afshars?

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 12-18-2006 12:28 PM:

Sorry, Horst,

The thing is is that this splendid rug has so many past

and future relatives that it's almost an overwhelming temptation to resist going

into comparison mode. The rug really deserves better, I think, on second

thought.

For one thing does pinpointing it's designation as being woven

anywhere, based only on it's color, pass for anything these days on a rug such

as this? If it does I think the party is over before it begins. If it doesn't,

and there is good structural analysis which has been done on it, that is the

real place to start analysis from if things are to be put into perspective

anytime soon -- as in any of our lifetimes. Has that been done? Is it available

to the public? Can you put it out here?

In the meantime, and this is only

a by the way type question, what the heck is this A-28 Vakiflar museum rug with

the Spanish looking gol? Is it a wargireh or something? Sue

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-18-2006 03:57 PM:

Richard, Patrick, Sue,

I am glad you enjoy it. Patrick, this is

excellent visual memory you are demonstrating, as well as an introduction to my

next post. Sue, as to the dragons' red eyes blinking from the rug, even the

specs I put on were to no avail - I'll try again later with the help of a glass

of port.

As to structural analysis, I could try to find out with the help

of Stefano and the museum staff. However, when it comes to a 300 years plus time

gap between Cat. 4 and 19th century rugs available to us for comparison, the

often stressed rule of 'designs wander - structure stays' may not be strictly

applicable. I agree, the Karapinar attribution might not be the ultimative

answer.

Yes, Vakiflar A-28 looks rather experimental. Perhaps it can be

put down to the never ending East meets West experiment that had already been

played on rug stage for 500 years at the time of its creation.

Bye for

now,

Horst

Posted by Richard Larkin on 12-18-2006 05:01 PM:

Hi Sue:

With oodles of trepidation, I say: Dragon? What dragon?

Patrick:

I'm a life member of the South Persian rug fan club, but

I'm not so convinced of the connection between that Basiri motif and the #28

from the Vakiflar. On the other hand, the redolence of latter day Turkoman gols

in that thing really gets one's attention. No doubt, the connection has been

noted elsewhere. By the way, thanks for the opportunity to look in on that

excellent salon you put together on those Balishts. I'll go back to

that.

Horst:

"Splendid" is just the word for that piece. It's the

kind of rug that makes one want to forget about most of the others. The analysis

by Kristine Klose is most intriguing. I often find discussions of design

evolution and migration a bit tedious, but discerning the connection between

early anatolian weavings and later, disciplined Turkoman weaving is usually

interesting. Thanks again for the excellent salon.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Wendel Swan on 12-18-2006 05:21 PM:

Hello Horst and all,

I agree that the Brasov rug is splendid, but I’m

having difficulty understanding the relationship between it and the drawings of

the classical “stars and crosses” pattern. The Brasov carpet does not have

either 8-pointed stars or conventional cross forms and I cannot find any

juxtaposition of even the most imaginative variation of them in that

rug.

At each end of the field in the Vakiflar carpet, there is what one

could construe as ornately stylized variance of the stars and crosses

pattern.

Indeed, there is a relationship between Turkmen weavings and the

stars and crosses pattern. I made reference to it in a lecture I recently

delivered to the New England Rug Society. Their newsletter reproduced some of

the images I showed in that lecture, one of which compares a well-known Chaudor

engsi and tilework from a 14th Century tomb in Samarkand. You can see that

comparison here:

http://www.ne-rugsociety.org/newsletter/rugl142a.pdf

In

that newsletter you can clearly see that Islamic art patterns can be seen in

various media.

Perhaps I’ve missed the point of including drawing of the

stars and crosses pattern.

Wendel

Posted by Steve Price on 12-18-2006 05:29 PM:

Hi Folks

I'm never sure, but I think this is the motif that Sue sees

as a red-eyed dragon.

I'm reluctant to read too much into it, since my first reaction

is that it's a cartoon locomotive coming straight at me. Note the cross on its

apex. Hmmm.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 12-18-2006 05:48 PM:

Hi Steve:

Thanks, I was looking in the wrong "corner within a corner."

The red-eyed dragon and the runaway locomotive interpretations are about equally

compelling, I would say. How about a salon on "Messianic symbolism and Wily

Coyote in the weavings of Eastern Anatolia?"

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 12-18-2006 07:29 PM:

Pesky dragons!

At the very top of the field, just above the red outline of the uppermost of

the three main medallions, is a thick, blue "spandrel" on either side.

Note

that these spandrels contain several red spots and where the dark spandrels

notch into the red, towards the middle of the upper medallion at the very top of

the field, the dark blue appears to look like the head of a bird (or dragon -

because of the spots) with a red eye and a hooked beak, facing

down.

Caucasian Dragon rugs have dragons with spots in their bodies and this

may be what Sue is seeing.

These "dragons" are 1/4 of the half-guls

bordering the field, a composite of which is shown by Horst at the bottom of his

first post. This composite, though, does not contain dual dragon-heads, but

instead "anchors" at either side of the gul.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Steve Price on 12-18-2006 08:10 PM:

Hi Pat

Perhaps Sue will pop in to clarify before too much time gets

spent trying to decide what she was talking about.

Steve Price

Posted by Richard Larkin on 12-18-2006 08:57 PM:

Patrick,

Of course. That's the fetal dragon, upside down. Fetuses,

like rugs, don't care whether they're right side up or upside down. Now, if we

can pin down Steve's locomotive, we're golden.

__________________

Rich

Larkin

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 12-19-2006 12:24 PM:

HALLELUJAH!!!

Patrick, God love you, thank you, and hallelujah!!!

You not only

found the fetal dragons but explained them better than I was trying to figure

out how to! Sue

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-19-2006 05:31 PM:

Hi all,

I love the funny cartoon locomotive. To me it is a promise of

things to come, playing the electric railway with the children after

Christmas.

Those dragons on the other hand are weird, as if the weaver or

designer has intended to play on our reflexes. There seems to be nothing in the

shape of the black composite medallion urging the shape he or she has given to

the figure. The very small red corners add to it, they make the difference

between an ordinary (a solid) corner solution and the sleek shape of what you

are suggesting. I've looked at the picture a hundred times and did not see it,

well scouted, Sue, Patrick. Three of the four red dots are actually small

Holbein knots, tells the better resolution image in the

catalogue.

Wendel, those black medallions are the same cruciforms as

those in A-24, only somewhat misshapen and sintered together. If you go down the

vertical axis there are nine eight-pointed stars within octagones; and six more,

that is three on either side of the axis within those individual medallion. In

other words, five within each of the individual medallions. All

clear?

Thanks for the interesting link to the New England Journal ( I

only new the medical one so far); I had a look in between patients today, and

will take a deeper one as soon as time allows.

Bye for

now,

Horst

Posted by Wendel Swan on 12-20-2006 03:52 PM:

Hello Horst,

I now understand why you made the comparison. I was

looking at the drawing as a tessellation comprised of two forms (the 8-pointed

star and the cross) so as to completely fill the plane without gaps or

overlaps.

The stars and crosses pattern is widely used in tiles, with one

example from Samarkand being in the NERS newsletter. Others have larger fields

similar in concept to the first drawing. Examples from one well-known set are

found in the V+A and in the David Collection that is at Boston College through

year-end.

While I understand the point, the principles of tessellation

aren’t really necessary to string together three or more medallions via

translation.

More interesting to me is the tessellation in the Vakiflar

rug formed by the blue outline at either end of the rug. That tessellation has a

relationship to the stars and crosses pattern, but one must look beyond the

decoration found within them.

Wendel

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-22-2006 10:25 AM:

Hello Wendel, Hi all,

It took me some time trying to work out what is

meant with ‘tesselated’, as this turned out to be beyond the scope of my Concise

Oxford Dictionary; even the ‘Advanced’ version did not make it much clearer:

‘tesselated (adj) formed of small, flat pieces of stone of various colours (as

used in mosaic): a ~ pavement.’ I imagine it to be something like a

‘Terrazo-floor’, made up of small stones of various greys and browns etc., the

kind of suggesting funny figures which you have difficulty finding again on

second look.

Unfortunately, I got caught up it all sorts of competing

activities and it will now take until after Christmas, that I can introduce you

to ‘inductive-deductive’ research method and invite you on a reconnaissance

tour, that will lead us outside Ottoman Turkey, because that is where I expect

the key to the understanding of Cat. 4 can be found.

Best Wishes for a

Merry Christmas,

Horst

Posted by Wendel Swan on 12-27-2006 09:21 AM:

Hello Horst and all,

Some images for you to ponder:

On the left is a classic

example of the crosses and stars tessellation (2 forms) in tilework, with this

example being at the V+A. Another section is in the David Collection.

I

created the middle image from portions of the Vakiflar rug, joined so as to

create a variation of the stars and crosses pattern.

The last image

relates to the second drawing, but is far less interesting, at least in my

opinion, than the tesselllation.

Happy New Year,

Wendel

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 12-27-2006 01:42 PM:

Hi Wendel, and Everyone,

These are nice to ponder but it is important

to remember that the mathematics behind the tiles' and the rugs' formatting

mostly preceded Islam's work in the field and so one expression of them need not

be derivative of the other.

On closer examination the Vakifar rug

formatting is different from that used in the tiles. An additional invisible

design formatting devise enters the equation in the rug that was not utilized in

the tiles. To understand this additional "third factor" one must look beyond the

"decorations" found within it, too, as both the "star" and "cross" motifs

intrude on it, making comprehension of it difficult.

This "third factor"

used in the rug, but not the tiles, is adjoining hexagons. The hexagon

formatting can be seen by temporarily ignoring the "crosses" as motifs so as to

see that the blue rectangles within the "crosses" share an outer border with the

"star's" guls to form the hexagons' diagonal outlines.

The vertical side

lines of the hexagon's outlines touch the vertical axis lines that run

vertically through, and beyond, the "cross" centers.

The horizontal

outlines of the hexagons are formed by the horizontal axis lines that run

horizontally through, and beyond, the "cross" centers.

In other words,

the math behind these compared ponderables differs in important ways.

Now

I'll just patiently wait for Horst to continue in hopes he intends to go on

about the splendid rug's gable birds so I don't have to. Sue

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-28-2006 04:51 PM:

Hi all and thanks for your patience,

tesselation is clear to me now,

thanks, Wendel, for ‘untesseling’ (?) it. While both patterns seem to follow the

same ‘mathematics’, Sue, I agree, the rug looks wilder, less integrated. In the

case of the tile pattern assimilation of designs seems to have reached a stable

level, probably the result of skilled workshop practise; the rug design seems to

have not ‘arrived’ yet.

Back to Cat. 4 - what follows first is an

ultra-brief summary of ‘inductive-deductive’ method (the term in this context

being as experimental as is the method): confronted with a (rug-research)

question, a given structure (knowledge, individual brain, work-group knowledge)

is formulating a position (deduction), which may not be satisfactory (dilemma)

and requiring the assimilation of additional knowledge; the landscape of

potential information is sounded out or tested (induction), the echo or

resonance or answers are subjected to assessment and if satisfactory are

assimilated to the given structure (knowledge, individual brain, work-group

knowledge) which itself accommodates to the new evidence or

findings.

Process on the interface of known and unknown: define (as many)

occurrence (-s) as specific as possible, test or ‘sound out’, record and

compare; the more resonance on as many variables / occurrences as possible, the

more reliable the newly gained information.

In practice:

We have a

rug of typical village produce size (occurrence 1) with broad kilim ends

(occurrence 2), containing a triple-medallion-form (occurrence 3) with halo

(occurrence 4), made up from cruciforms like on some early Central Asian rugs

(occurrence 5) and göl-like shapes (occurrence 6) of a particular kind

(occurrence 7). We also have a meandering main border of a leafy kind

(occurrence 8), forming reciprocal gables (occurrence 9) under which locomotives

with a cross-shaped funnel are waiting to be let loose (occurrence 10). This is

for demonstration; we could include colour constellation, symmetry, the blue on

black ornaments being half göl, half star, the central stars within octagons

etc.

This is the resonance we get (pre-selected cluster):

Afshar

and other South Persian village rugs (occurrence 1, 2 - Tanavoli P (1988, 1991)

The Afshar Part 1 and 2, Hali 37, 57);

Wide variety of North-, West- and

South Persian village and nomadic rugs (occurrence 3):

South Persian

Afshar rug from Kerman province (occurrences 4, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 – see

images):

Vakiflar A-28 and another East Anatolian parallel rug,

apparently differing only with regard to the damage to the sides (occurrence 5,

6 – Ellis C G (1978) The Rugs from the Great Mosque of Divrigi; plate 28 Rug

with ‘Turkoman-gül’ design);

West or Northwest Persian Afshari rug

with a related, stylised border of same type (occurrences 8, 9,

10):

Considering a 300 - 350 years time gap between Cat. 4

and the late 19th / early 20th century reference rugs, the ‘echo’ is remarkably

stable. The South Persian Afshar rug with ‘Turkoman Göls’ from Kerman province

resembles at least one rug closely, that is depicted in the Ralph Yohe article

on the Yörük triangle (fig. 7). Divrigi with its Ulu Cami, one of the reference

locations, is a few hours east by railway from Sivas towards Erzincan, deep in

the Yörük triangle.

Of the ethnic groups mentioned by Ralph Yohe, one

more than any other it seems can be associated with Cat. 4, the Afshari, one of

the original invading Oghuzs, who for centuries had settled in East Anatolia and

Azerbaidjan, before the Azerbaidjani factions were resettled south in recurrent

waves, taking designs with them, that went on being woven by their Anatolian kin

for a long time, possibly until the middle of the 20th century.

This does

not per se exclude the possibility that the loom on which the rug was made was

set up somewhere in West or Central Anatolia. We know from earlier discussions

here how the eventual realisation of influences due to past tribal movements

have played havoc with neat attribution ideas, i.e. East Anatolian or Caucasian

designs in the Aegean region (Kazak-Kosak) - but here it works for us and makes

an East Anatolian or Azerbaidjanian attribution much more likely (some rugs may

have been made far west, whilst the design’s origin is in the east).

I am

aware, that the attribution put forward here, may lead to other question, i.e.

the validity of a Karapinar label and, possibly, the attribution to West

Anatolia of a number of other rugs of the ensemble. This may be for future

consideration.

Regards,

Horst Nitz

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 12-29-2006 12:11 PM:

Horst,

The overlay of an invisible hexagonal formatting was not

utilized, nor necessary, in the tile work's design. The problems within the rug

Wendel compares the tile work to are a whole different, and very interesting,

story.

I was trying to explain why a comparison between the tile's and

rug's design formatting was an apples and oranges comparison. So that point was

missed.

The comparisons you are now making resonate only with Wendel's

comparison, to me. I don't see any application that can be made with these

comparisons in understanding the splendid rug. Nor do I know what to do about

such misunderstandings other than to point them out. Sue

Posted by Horst Nitz on 12-31-2006 02:19 PM:

Hello Sue,

I've tried more than once but seem to be unable to get the

knack of it: 'invisible hexagonal formatting was not utilized, nor necessary, in

the tile work's design ...'. I don't know whether it is my limited command of

English or eye-sight or something else. I may have to let this one pass this

year.

Wishing all

of you a Happy New Year,

Horst

Posted by Sue Zimmerman on 01-06-2007 02:57 PM:

As an interesting aside, the real "experimental" Vakifar rug, as seen without

computer manipulation, reveals an attempt to reconcile it's mathematically

derived differing hexagonal formats, (as shown visually expressed in it's

differing motif areas), unsuccessfully.

This clash of hexagon formats

can be most clearly seen in the area of the four central horizontal motifs of

the rug. The "invisible" differently formatted hexagon's outlines being found in

the surrounding red field between the motifs. The Vakifar rug looks, to me, like

a failed math problem made visual.

I find this "experimental" rug rich

in lessons. For one thing understanding what went wrong bypasses, for observers,

having to actually know the math equations which would have led to a successful

resolution of it's rather simple "story problem". That something of a more

abstract nature was lacking is undeniably visually apparent in this rug. It

points out that the weavers of this rug did not have access to what would have

allowed smooth resolution of the sizing disparity of it's two hexagonal "3rD

factor", (as I'll now call it,) formatting, (amoungst other things I'll not

touch on here).

"Traditional" methods of formatting, even within

traditions where this 3rD factor formatting tradition was used, as it apparently

was for these weavers, whether learned by counting knots, other forms of rote

memorization, or knowledgeable "over the shoulder" guidance, etc., when

presented with merging and/or reorganizing motifs, from even equally

knowledgeable parallel traditions, or even from within one unparted tradition,

the abstract basics behind the designs are necessary to call upon, sometimes, as

they were for this rug, and clearly here, the call was unanswered.

There

are implications far and wide in this rug, in other words, as worthy of further

exploration in rug studies as any other pursuit, as I see it, because it is of a

fundamental and overarching nature. That is why I am attempting to share it here

despite it's off topicness.

For those who would like to give it a try but

don't understand what I'm trying to say, here's what you can do, on the cheap.

Print out a copy of the "experimental" rug. Tape tracing paper over it and

connect up the "3rD" factor of the formatting, the hexagons, with a pencil and a

ruler for further contemplation.

For those who cannot see any reason to

try to understanding this concept, or dismiss it entirely, here's something easy

to contemplate. A two dimensional drawing of a hexagon can be thought of as the

silhouette of a three dimensional cube. Draw a hexagram and then add the lines

necessary to make it a cube. Now open a rug book and compare your drawing to,

say, what appears within a good old Salor Kejebe motif, for instance. Some will

get it, I think. A few, those who like old Turkmen chuvals, for instance,

already have caught on, but maybe I'm wrong. Sue

Posted by Horst Nitz on 01-15-2007 03:51 PM:

Hello Sue,

the hexagon as the projected silhouette of a cube, an

interesting idea and something I have never thought of, or have forgotten of

since school days. However, what is the significance of it in this context? I am

sorry, I can't make head or tail of what you are

saying.

Regards,

Horst Nitz

Posted by Horst Nitz on 01-28-2007 12:35 PM:

Dear all,

I am very grateful for having received structural data on

the 3-medallion rug cat. 4. from the Black Church in Brashov. This I would like

to contrast with data on the Vakiflar A-28 rug from Balpinar B & Hirsch U

(1988) Carpets of the Vakiflar Museum Istanbul, that we have been discussing; to

make this threesome complete, I shall use data on one of the not too many

published Afshari rugs that come with such: plate 10 from Tanvoli P (1991) The

Afshar, Part 2. HALI no 57, June 1991, pp 96-105 (below):

Structural data is

given as presented by the authors.

Cat 4:

Warps Z2 ivory wool

moderate compression

Wefts wool Z red-brown, two shoots, one straight, one

sinuous

Knots Gjordes (Sy) wool Z, 2-5 mm, 28-30 x 35-38, partly corroded

dark-brown

A-28:

Warps Z2S ivory wool

Wefts wool Z light red,

2-3 shoots, sinuous

Knots 2Z Sy1, 23 H x 32 V, 736 kpsdm

Plate

10:

Warps ivory wool Z2S

Wefts wool Z red two shoots, one straight,

one sinous

Pile Sy wool Z 4-5 mm, 40 H x 36 V, 1440 kpsdm

As you

can see there is not much in the way of contrasting structural data. It is all

rather similar. The ivory grounded Afshari rug with Göls and a sort of

Chintamani and lattice-ground design presented further up, shares these

structural features.

This suggests that the rugs discussed here share

much of their ancestry, which appears to have its starting point - as far as age

attribution is concerned and, taking into account what was said further up - in

East-Turkey and West Azerbaidjan.

Regards,

Horst Nitz

Posted by Steve Price on 01-30-2007 01:31 PM:

Hi Horst

That's a great demonstration of chasing down substantial

evidence and applying it to test a position. Rugdom would benefit from lots more

of this kind of analytical thinking.

Regards

Steve Price