by R. John Howe

On October 7, 2007, Jerry Thompson presented a Textile Museum rug morning program on Persian city rugs, in modest congruence with the current Pieces of a Puzzle exhibition treated here in an earlier show and tell thread.

Jerry is a long-time collector-dealer in the Washington, DC area. He joked that he has been handling such rugs for over 30 years and is beginning to “catch on” a bit about them.

The Pieces of a Puzzle fragments are mostly from 16th and 17th century carpets attributed to Khurosan, nowadays seen at northeast Iran, but in that time, defined much more broadly. What we now describe as Persian city rugs are most usually rugs and carpets woven in the late 19th to the early twentieth centuries in such cities as Kerman, Kashan, the Sarouk area, Tabriz, Ishfahan, etc. Persian city rugs are usually curvilinear, woven following a set design of some sort, and are frankly commercial products, some woven under the auspices of western rug weaving operations (like Ziegler) in Iran.

Most Persian city rugs would not attract the attention of collectors much, but some instances of them rise above the ordinary and Jerry is a collector who does collect some city rugs. Wendel Swan is also, I believe, attracted to them, and I would expect that Harold Keshishian could produce more than a few if asked.

It is difficult to find interesting pieces for a session on Persian city rugs because many of them are room size and too heavy and awkward to bring into the TM and to display on the board in the Myers room. Pieces need to be about 4 x 6 or 5 x 7; 6 x 9 begins to approach unmanageable. So Jerry did not pretend to have examples from all the cities that produced them, but offered a nice, informative sample in his program.

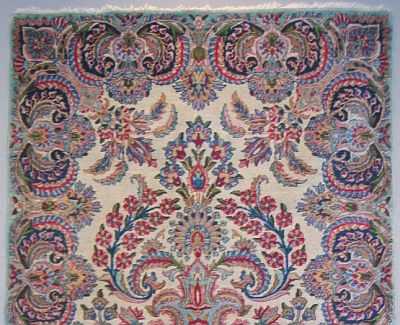

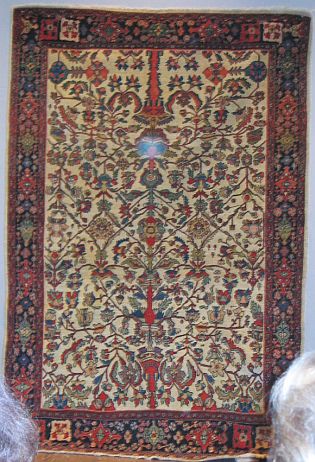

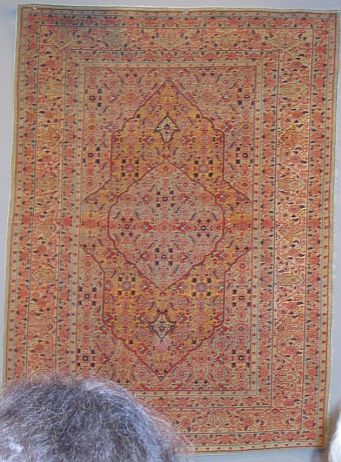

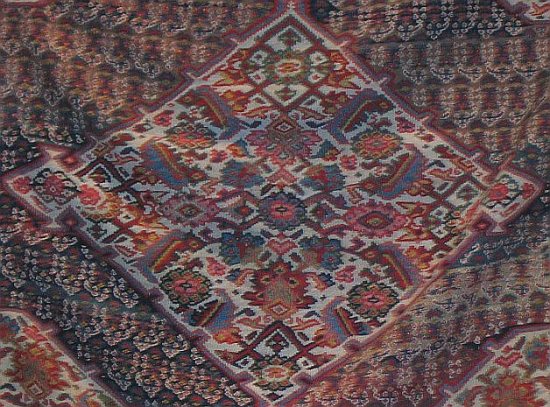

He began with a piece woven in Kerman.

He said that this is a good beginning example of a Persian city rug. It displays some of their frequent characteristics. First, it seems very likely to have been woven following a design (perhaps a graph paper cartoon) that indicated, knot for knot, what this design in what specific colors should look like.

The indicator for this is that the drawing on it is nearly perfect. That is, no irregularities are displayed. The design is one that could have been woven from a cartoon that contained only one quarter of this whole. The weavers could mentally reflect the cartoon to produce the full top half and then reflect that half on a horizontal axis to produce the lower half.

Another sign that this Kerman piece was woven from a precise, predetermined design, Jerry said, is that it has perfectly resolved corners on its borders.

That is, the borders approach each corner and then move around it smoothly with elements of the border drawn at a 45 degree angle in each corner. Such resolved corners are also sometimes described as mitered, a reference to the shape of some ecclesiastical hats.

Jerry said that this rug does not achieve the excellence of the old Kermans that so enthralled Edwards in his classic The Persian Carpet, but it does have (not counting shades) about 13 colors, about twice what one encounters in most rugs.

He estimated that this piece was likely woven about 1920. He said turn of the century Kermans would have been thinner than this one is and that, about World War II, Kermans took on washed-out colors and medallion designs with large areas of open field.

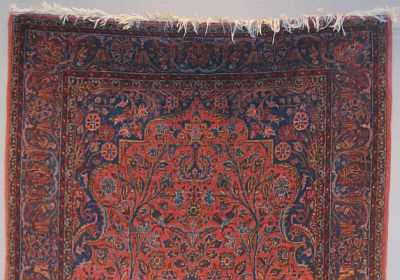

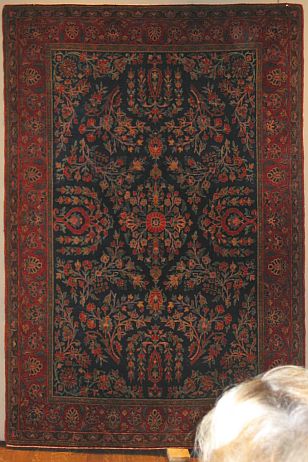

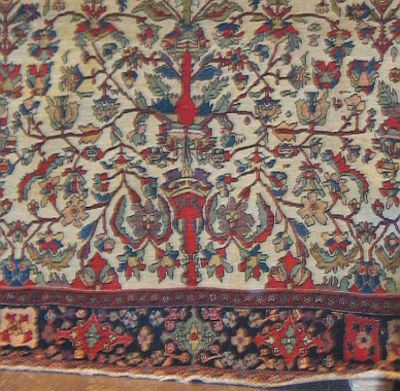

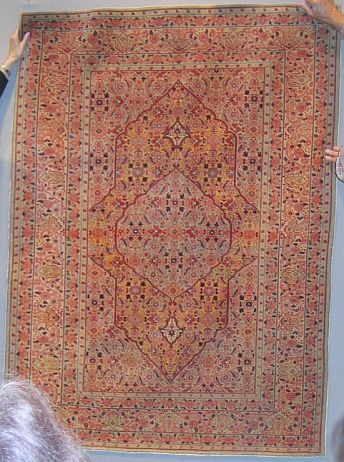

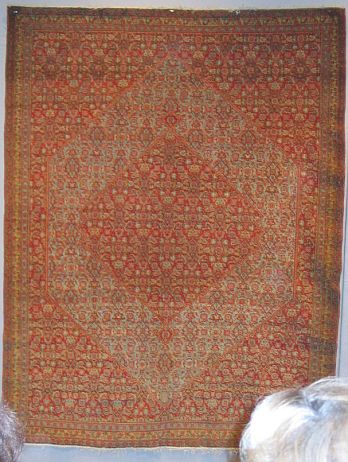

Jerry describe the next piece as a Manchester Kashan.

He said that the story about such rugs is that in the late 19th century the Kashan shawl industry collapsed. There were, though, large amounts of high quality wool about that had been processed in Manchester, England. In some way or other, weavers began to weave carpets with this wool. Jerry said the production seems to have lasted only about 20 years but today Manchester Kashans are a type of city rug to which many collectors pay serious attention.

This example has wonderfully soft wool, with pile longer than needed, and a niche design. Again, very precise drawing, likely following a cartoon. Nice birds are featured.

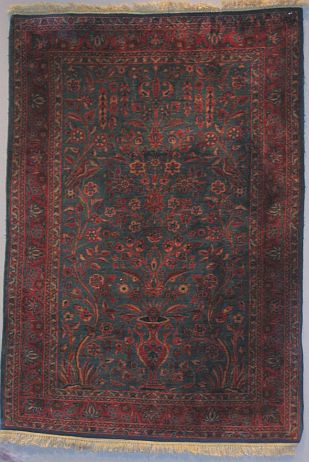

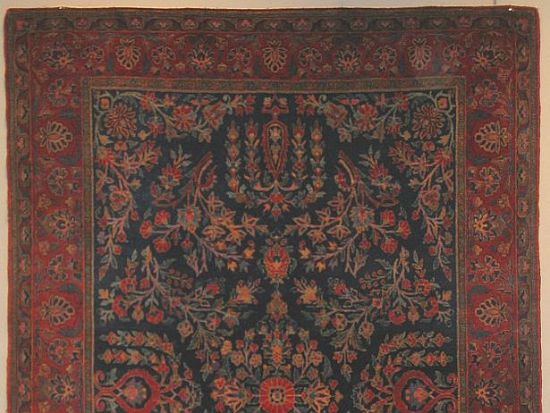

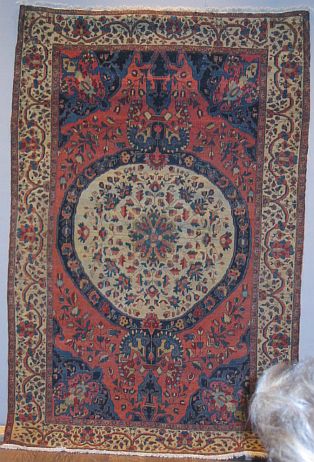

Jerry next offered another Kashan, the wool of which was

likely produced locally in Iran but which is again of a very high

quality.

He said that in the trade the wool of this rug would be described as kurk wool and is reputedly that taken from the necks of young sheep during the spring shearing.

Birds and vases are common in such Kashan designs. He

estimated that this piece was woven in the early 1920s. Jerry said that

the ends of this piece have been restored.

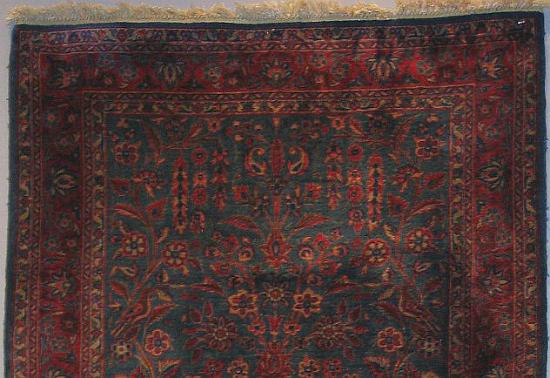

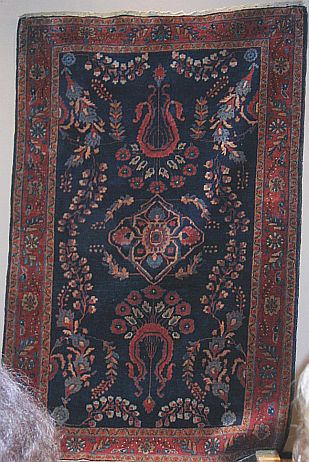

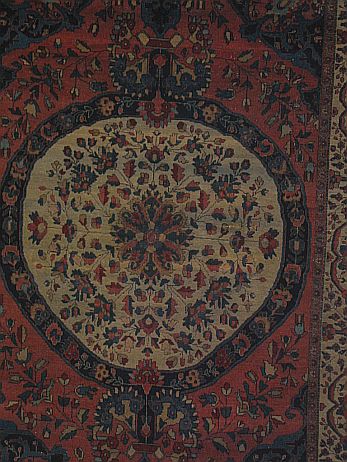

The rug below is also a Kashan, estimated to have been woven in the early 20th century. Jerry said this rug is noticeably fine and thin.

He said (I not sure he was referencing this piece in doing so) that there were some identifiable workshops in such cities as Kashan and Tabriz and that some feel that they can identify rugs woven in them. Perhaps the most famous workshop in Kashan is described as Motasham.

There are questions about whether rugs woven in this precise workshop can be identified. Some say that more pieces are claimed to be Motasham than could conceivably have been woven in a single workshop from the later 19th century into the early years of the 20th and that the term is now likely an article of dealer hype and to be avoided. But others (I have heard Harold Keshishian make this argument) say that Motasham pieces often have technical features that permit at least probably identification (one is that they are claimed usually to have pink silk selveges).

Jerry said (and he may, now, have been referencing his rug

above) that some claim to be able to recognize “son of

Motasham” pieces.

As we were discussing the piece above, Richard Isaacson, asked from the audience, “How do you know that it is a Kashan?” This is a good question, since although Kashans have technical features (i.e., asymmetric open left knots and blue wefts) that clearly distinguish them from rugs woven in Tabriz (the latter have symmetric knots very uniform looking because they were woven with a hook), the former could be difficult to distinguish from some Sarouks that use the same knot and also have blue wefts.

Jerry’s response, I think, ultimately suggested that he personally uses a species of what Neff and Maggs call weave pattern, that is the overall appearance of the weave on the back. Neff and Maggs, in their description of Kashan vs “old” Sarouk weave patterns say that in Kashans the “weft is sometimes barely perceptible” while with Sarouks “each weft line is visible along its complete transverse and varies in thickness". They also say that there is something distinctive about the shape of the knot nodes of both Kashans and Sarouks, but don’t describe these shapes concretely.

My guess is that having handled many Kashans and Sarouks over the years Jerry has developed an ability to “read” the differences in their respective weave patterns in a gestalt way that he does not necessarily fully articulate to himself. But the difference in weft appearance alone would seem to be a pretty reliable basis for making this distinction. Interesting stuff.

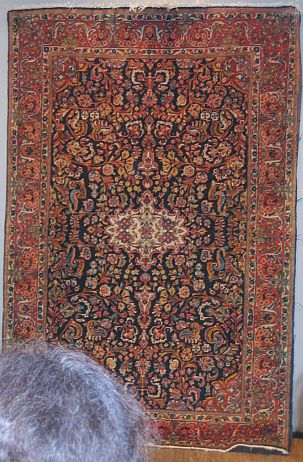

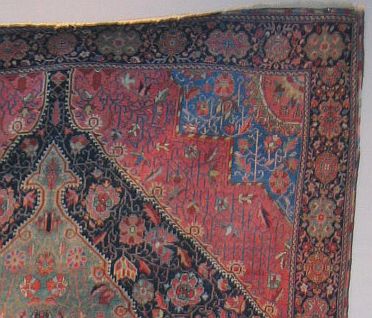

The next rug was the first of the Sarouks presented.

Jerry said that although this piece has asymmetric open left knots and blue wefts, like the Kashans, it has a coarser weave and more open design and is seen likely to be what is described as a Mahasuran Sarouk (that is, one woven in a particular Sarouk workshop). The blue background of its open field is somewhat rare for a Sarouk. It is carefully drawn but has detectible variations in its drawing that suggest that while weavers were likely consulting a cartoon, they were not following it on a knot-for-knot basis. Jon Thompson has analyzed the Ardebil carpets, found similar variations and has suggested this conclusion.

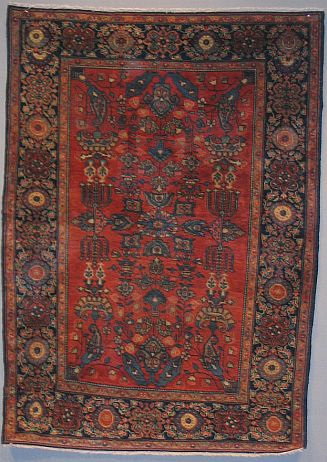

Jerry described the rug below as “more or less” a Sarouk.

He said it has nice wool and at least ten nice colors. It has

what western eyes might read as a German Maltese cross, but this device

may have had difference meanings for the weavers. It is estimated to

have been woven in the first quarter of the 20th century.

Jerry hung the piece presented so that the pile points down. Some of the audience asked that some of the piece also be turned 180 degrees on the board (same side out) so see what difference that made in the way the colors looked. This is the first one on which that was done. The image of this rug above is with its pile pointing down. The image below is how its colors look with the pile pointing up.

Just a word of explanation for readers who may not be familiar with what we’re talking about here. The pile on an oriental rug does not usually stick out at a perpendicular from the foundation. The weaver ties each knot around two warps, pulls it down and cuts the two projecting strands off at some give approximate length. So the knots of a finished rug “point” down. Because of this light is reflected differently of the pile when viewed from one end or the other. When viewed from the end toward which the pile points, light tends to hit the ends of the pile, more of it is absorbed and the piece appears darker. When viewed from the other end (pile now pointing away) the colors in the rug will seem lighter or milder. This works a little differently when we are looking at rugs on the board in the Myers Room at the TM. There are lights directly over the board and so when the pile points down there, it mostly reflects of the sides of the knots and the colors are milder. But if the rug is reversed so that the pile points up toward the lights, the colors on the rug appear darker.

Jerry joked that when he is showing this phenomenon to a potential customer he avoids the terms lighter and darker as potentially pejorative, and says instead that this is the richer end of the rug and that is the more subtle end.

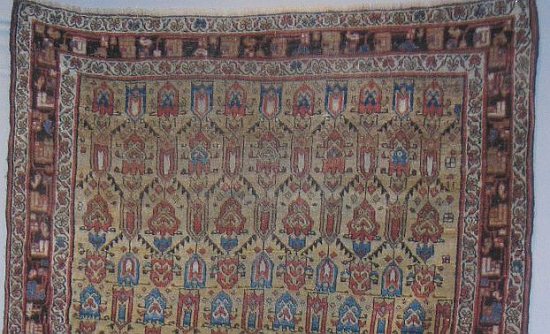

The next piece, below, is a Farahan Sarouk. Jerry said that the Farahan distinction is usually applied to a Sarouk when it has a noticeable amount of green in it.

Jerry said that the drawing in this rug might be described as a little "wacky,” that is it has places where the design seems eccentric. The irregularities in this piece indicate that is was likely not drawn with much reference to a cartoon.

It has an ivory field, the corners of its borders are

“butted” rather than “resolved”

or “mitered,” and it has a synthetic red dye used

in its field. Still it has considerable age and is estimated to have

been woven about 1890

Jerry described the next piece, below, as a Sarouk variant. It has lots of green and so might well be a Farahan Sarouk, but also may not be.

Jerry drew attention to the rather rectilinear lattice in the field of this piece and asked, “Where do they do this?”

His own answer is “Jozan.” He suspects that this is a Jozan Sarouk. Jerry said this piece shows a lot of mistakes and failures in drawing but it is fairly old, perhaps 1890-1910.

Jerry said his next Sarouk was an early one.

He noted its unusual design. He felt it possible that it is a Mahajorm (sp?) workshop Sarouk.

The rug below is the only Tabriz that Jerry showed.

He drew attention to its totally different palette (in truth Tabriz rugs are known for their wide variation in both design and coloration). Jerry said that this piece was made for market, but that he thought that it might be defensibly seen to have been woven by the Haji Jalili workshop in Tabriz.

He described it as “more subtle than dynamic,” and said that he loves the yellow. He said that the selvages are original and unusual in that they were two-cord rather than the expected single-cord. He said this rug hangs in his office.

Folks in the audience asked to see it reversed on the board.

Viewed in that orientation the colors are, as Jerry would say, richer.

Jerry said that this was the end of the strictly defined “city rugs” that he wanted to treat but that he’d left himself a little “wiggle” room in his title in order to license his showing us some pieces woven in Bijar and Senneh.

The piece below is a Bijar but not a typical one in some respects.

It has a loose handle, a yellow field and an unusual design.

Jerry said its drawing has a “country boy copies city boy” feel.

A second Bijar was a more recent piece with chemical dyes.

It was brought, I think, primarily to have an example of a more typical Bijar structure and handle. This one was of the “iron rug” variety. Among its other non-city features are the fact that it is not straight, its proportions are visibly off, there are mistakes to be seen and the corners of its borders are not resolved.

Jerry finished with pieces from Senneh: two kilims and a pile rug. The first of the Senneh kilims was a horse cover.

These kilims are in slit weave tapestry. They have small holes all over

them wherever there are vertical changes in color. Like many Senneh

kilims it has a tan and mild yellow palette with bits of black, dark

brown and/or white used as contrasts. Herati designs are very frequent.

This horse cover seems likely to have been used. It has diagonal areas

of repair on both front corners. Jerry said that Senneh kilim

horsecovers are fairly rare but at the most recent ACOR Jim Burns

suggested that Senneh horsecovers and saddle pieces are more

frequent.

But note that Burns’ Senneh example is pile and his only kilim example was not a Senneh, so maybe Jerry’s rarity estimate holds.

A second Senneh kilim was awkward but, to me, interesting.

Although full of quirky signs of uncontrolled or unplanned

weaving,

it had a greater range of color, variations in design, and changes in scale that made it appealing to me despite its obvious imperfections.

The third Senneh was a pile rug and probably the Senneh I should have liked best.

Carefully planned and precisely executed, it projected a nice serenity that might be something very good to look at at the end of a bad day. Jerry said that it has fine wool and pink silk selvages.

Jerry had said earlier that Schurmann claimed somewhere that there were folks who could identify rugs blindfolded on the basis of their handle. Senneh pile pieces are plausible candidates for such identification because their backs have a very distinctive sandpapery feel. Someone asked why that was and Jerry suggested that it was likely the character of the wool. Someone else in the room suggested that it might be the distinctive Senneh weave. The issue was left unresolved.

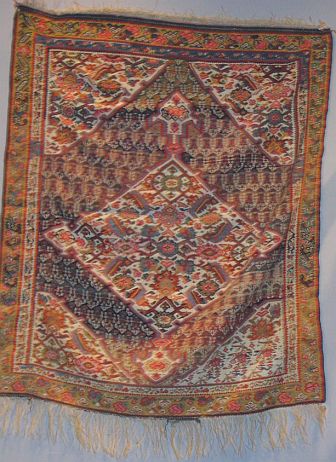

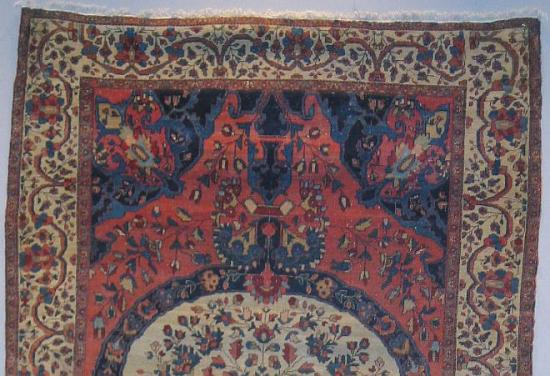

Only one rug was brought into this session by someone in the audience. It was this Sarouk with an unusual and striking design.

The drawing is full of awkward variations.

The circular medallion not quite regular.

But it has attractive colors (the red was questioned but the back suggested madder to Jerry), nice variations in design and scale that give the piece considerable visual impact. It was a nice rug with which to end a good and interesting TM rug morning.

Thanks, Jerry.

Persian city rugs populate the books that many of us have. So it might be interesting to attempt to fill gaps or offer other examples of given types. You are invited to do so.

Regards,

R. John Howe