Posted by Wendel Swan on 04-26-2006 03:46 PM:

The Anatolian-Scandinavian connection

Dear all,

Bob Mann and Paul Ramsey both identified this rug (correctly) as coming from

the Ushak area, with its large knots and distinctive color palette. The others

all agreed.

The inscription (if it is really writing) was unknown. Everyone agreed it was

highly unusual to see human and animal figures on a rug from that area.

The Ushak rug had a central medallion somewhat similar to the three found in

the next showing:

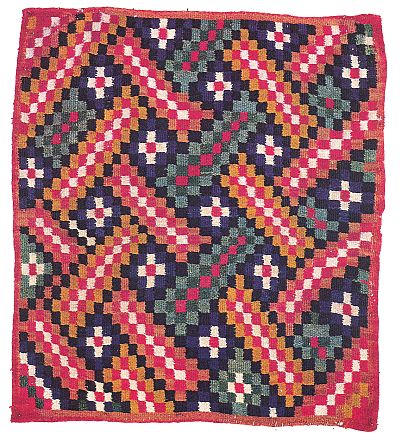

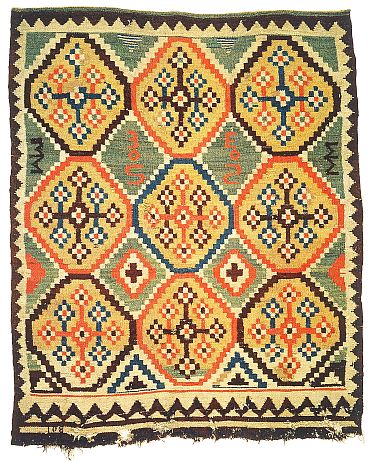

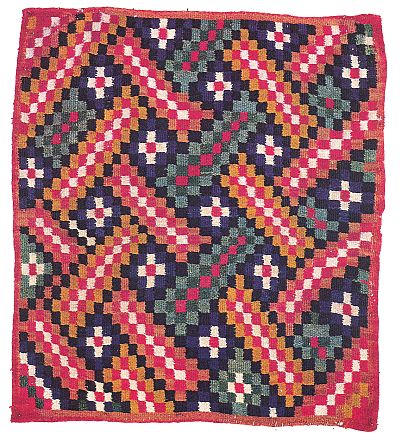

The medallions in this predominantly green Swedish cushion cover are Lottoesque.

Its Scandinavian origin didn’t fool any of the panelists, but I chose it because

this type had fooled someone in the past. This one and the other shown below

are both done in a type of petit point. At least I think that is what the structure

is called.

Many years ago at The Textile Museum, a prominent author and dealer in South

Persian rugs identified a complete flat-woven khorjin (with interlocking wefts)

as coming from a specific Qashqai tribe, to the astonishment of the collector

who brought it in. It was also Swedish. Few people know of the connection between

the Silk Route and Sweden.

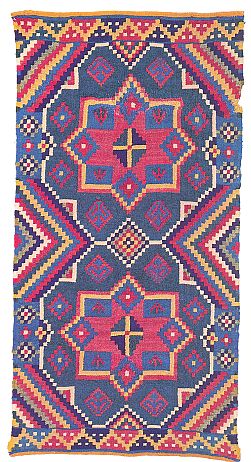

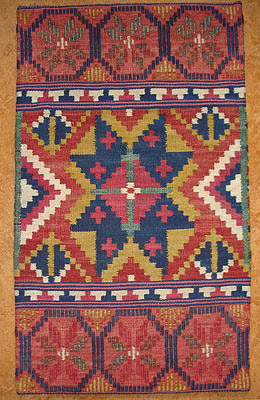

At ACOR 7, in his hands on session, Lawrence Kearny showed this Swedish cushion

cover, with graphics that are bolder. I inquired about buying it (mainly because

of my own Swedish heritage) but it wasn’t for sale.

The cushion cover in the Mystery Rug session was for sale and I took it home.

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 04-26-2006 05:55 PM:

Hi Wendel -

Coming home I bought two books on Scandinavian textiles. One of them, "The Woven

Coverlets of Norway" by Katherine Larson, was issued to accompany an exhibit

that traveled in the U.S. and Canada in 2001.

Her treatment indicates that such textiles were produced not just in southern

Sweden, but also in southern Norway.

"Rutevev" is Norwegian for the Swedish "rolakan. And "billedev" is Norwegian

for the Swedish "flamskvav" all of these terms, as you know referring to weaves.

Larson's book offers nice historical treatment of the Norwegian weavings of

this sort and nice color images of the items in the exhibition. She doesn't

refer to any formats other than the "coverlets," but it seems unlikely that

a range similar to that produced in Sweden was not also produced in Norway.

I mention this book because the literature seems often to move from "rolakan"

to a "Swedish" attribution and perhaps there are good bases for this move, but

apparently a distinction from similar Norwegian weavings needs to be made.

Thanks for the superior images of all of these mystery pieces. Either my camera

or its operator did not function particularly well. Are they Fred Mushkat's?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Lars_Jurell on 04-27-2006 12:38 PM:

Hello all

Here is a link to another Swedish cushion cover

http://www.akrep.se/akrepny/18E%20Skane%202.htm

and you can also look at number 16 in our Gallery on the site.

If you want some more information from Sweden about our textiles, just let us

know. But maybe it will take a week before we can reply.

Regards

Lars Jurell

Akrep Oriental Rug Society, Gothenburg, Sweden

Posted by R. John Howe on 04-29-2006 08:35 AM:

Mr. Jurell -

As I said somewhere else here, earlier this week I bought a book on Norwegian

coverlets. It seemed to suggest that most of the weaves (possibly most of the

formats) of these flatweaves were woven in southern Norway as well as southern

Sweden.

What's you understanding of the situation in this regard? Do folks in you area

distinguish such Swedish textiles from those made in Norway and if so what are

the bases for doing so? I notice that some attributions are quite precise (e.g.

Skane).

Thanks for anything further you can say here.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Sonny_Berntsson on 05-19-2006 11:24 AM:

Hello

Lars Jurell asked me for comments about Swedish textiles and here is a Swedish

"agedyna" ( cusion ) from Skane, Sweden.

Probably from the area between Ystad and Malmo.

Age: Around 1800.

You can clearly see the similarity to kilims from Central Anatolia and Cappadocia.

Here is also a Norwegian pillow for a chair, age 16th century.

It is very difficult to distinguish this types of textiles from Sweden and Norway.

Like to distinguish textiles from West and Central Anatolia.

How many experts can distinguish the two textiles above from 18th century Central

Anatolian textiles?

In my opinion Norwegian textiles show the oldest pattern and some of them are

probably from 9th - 14th centuries.

In Skane ( Sweden ) they started later with the weavings we call

"Skane-weavings". They used many different technics and pattern and some of

them are similar to them from the Byzantin period.

As usual one have to see a lot of them before having a theory.

We had an exhibition in Ystad some years ago to show similarity between Sweden

and Anatolia.

Regards

Sonny Berntsson

Akrep Oriental Rug Society in Gothenburg, Sweden

Posted by Wendel Swan on 05-19-2006 12:40 PM:

Hello Sonny,

Thank you for posting the two images, both of which are quite interesting.

In the first one, the section with the 8-pointed star seems to have been done

in interlocking tapestry, but the ends look like zili (over 3, under 1) brocading

that we see primarily in Anatolian weavings and some from NWP. I have not noticed

it in Scandinavian textiles.

The second image looks just like an Anatolian kilim. I am very curious about

the 16th Century date. Do you know how such an early attribution was determined?

It's not that I'm questioning that it could be that old, but I have to ask the

basis for such a date.

If you are aware of other structures comparable to those in Anatolia, please

post more images. I think the topic is fascinating.

Best regards,

Wendel

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-20-2006 07:47 AM:

Wendel -

You may want to borrow these two books I recently picked up. The one, on Norwegian

textiles, I have described above. The second one is "Flatweaves from Fjord and

Forest" with a text by Peter Willborg and edited by Black and Loveless.

From these sources it seems that "rolakan" is a term used to refer to a variety

of "tapestry" weaves that include the "slit weave" variety. Oddly, Willborg,

Black and Loveless give drawings of these different varieties of tapestry and

seem to say that although the Swedish weavers of rolakan use "slit weave" tapestry,

they use it only in diagonal applications in which the slits are only one weft

high. The Swedes seem not to see this as "slit weave" tapestry (the "slits"

are in fact hard to find) and call it "diagonal" tapestry.

These two books also suggest reasons for the "corded" appearance you have noticed

that can be seen as likely "zili."

Tapestry weaving can be done by varying the number of warps (or wefts) interlaced

in any one shoot of weaving. And, of course, the size of the warps and wefts

can be varied. One result of this is there are both warp-faced and weft-faced

tapestry weaves some of which have a corded looking surface that can be corded

either horizontally or vertically. But I see no indication that they actually

weave zili per se (one could argue that one possible variation in the number

of warps interlaced would produce a fabric identical to zili and that may occur).

But "corded" effects seem visible to me in a number of these pieces.

A third thing to which these books allude but do not really explain fully, is

that there are apparently some weaves that are the result of the insertion of

extra wefts. And some that exhibit cross-stitch on a tapestry surface.

The colors of some pieces in these two books is spectacular and some of the

palettes encourage me about the rolakan I own (which regardless may still have

been woven in Minnesota  )

)

Anyway, you are welcome to borrow these two books and to pursue them at your

leisure.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-20-2006 04:17 PM:

Dear folks –

I thought it might be useful to give everyone a few samples of the rollakans

presented in the two books I have mentioned above.

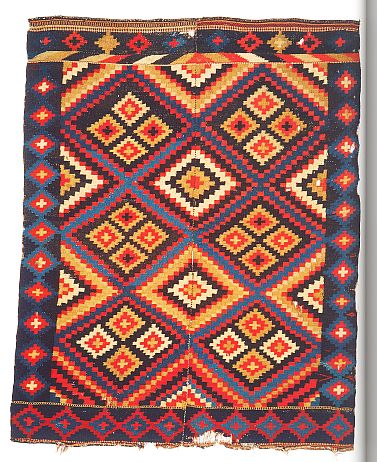

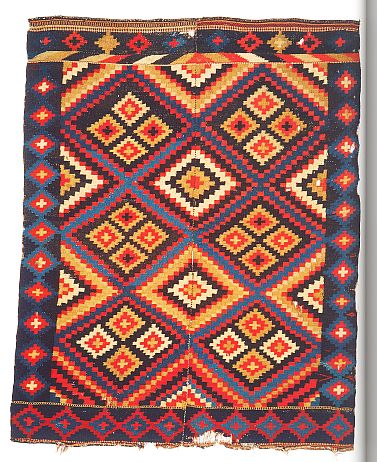

First, are the Swedish pieces from the Willborg, Black and Loveless volume.

The piece above is Plate 2 in this volume. The warp is linen and the weft is

wool It is considered a rare design. It is estimated to have been woven in 1800

or earlier.

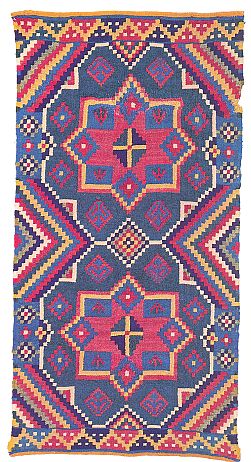

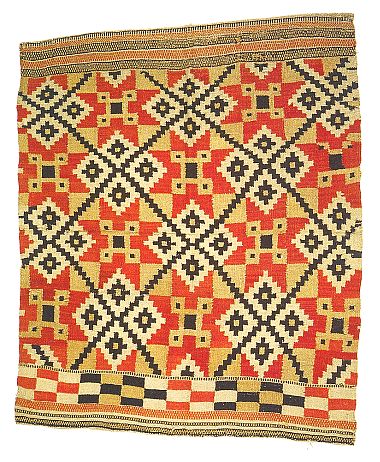

The weaving above is in the fashion of the Skytts and Oxie districts in south-western

Skane. Its larger size (107 X 56 cm) is an indicator used in this attribution.

Estimated to have been woven in the 18th century.

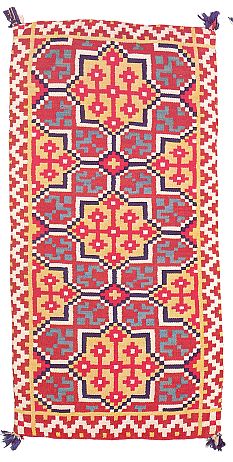

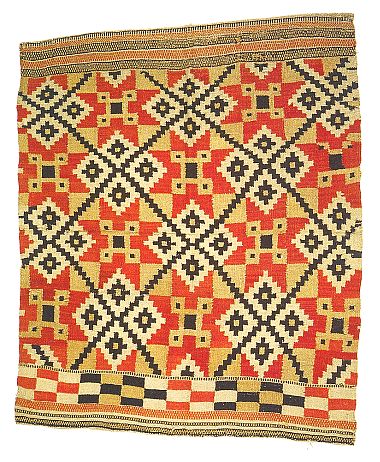

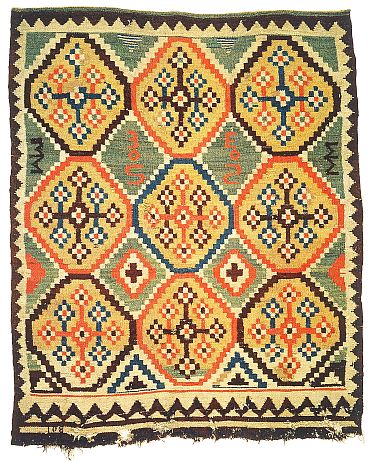

The attribution on the piece above is very precise. It was purchased in the

village of Veherod, the district of Tama, part of Skane. The design is found

throughout Skane. Around 1800.

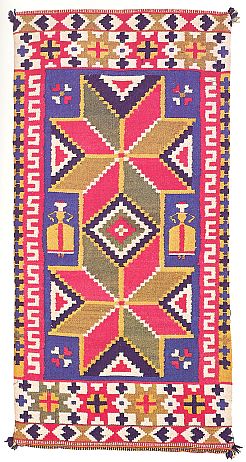

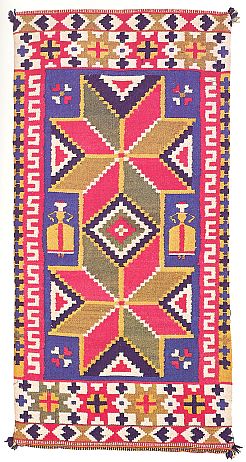

One commentator says that extreme stylization of the human figures in the rollakan

above occurs only in pieces from Jarrestads district in south-eastern Skane.

It's owner claims it came from the Oxie district. Early 19th century.

(By the way, that last two pieces have interesting backs which I have not shown

here.)

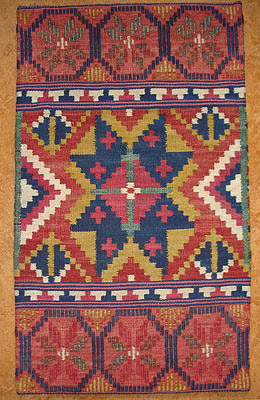

The author/editors say that this is one the most important pieces they have

found. Only one other instance of this design has been published. Both dated

1771. A vivid green on the front has faded to an indigo blue. Skytts district,

south-west Skane.

The three pieces below come from Katherine Larson's book on woven Norwegian

coverlets. They are all larger pieces, although Larson does not give measurements.

The coverlet below is done in a tapestry (Swedish: rollakan) weave that is called

"rutevev" or square-weave in Norway. The piece is attributed to Vest-Agder,

the southernmost district in Norway, on the basis of its design of rings composed

of concentric diamonds. Its darker colors are characteristic of coverlets of

southern Norway more generally.

The coverlet below is attributed to the Sogn and Fjordane district on the west

coast of southern Norway. No date is given but the pieces in the Larson book

seem more recent and some have 19th century dates. This is a piece that can

be read differently depending on whether one's eyes go more quickly to the knot,

diamond or eight-petaled star motifs that it contains.

The piece below, described as in the "nine-cross" pattern is attributed to Gudbrandsdal,

a norther sub-part of the Oppland district in interior southern Norway.

Willborg and company agree with Sonny Berntsson's indication above that it is

difficult to distinguish Swedish varieties of rollakan from those woven in Norway

but say that they do have somewhat distinctive features.

I wonder if it could be (at least for coverlets) that at least some of such

differences might not be the result of the fact that rollakan in Norway was

originally woven on upright warp-weighted looms that could accommodate the greater

widths of items like coverlets.

When horizontal looms appeared in Norway, the items woven on them had to be

narrower because of their structure. One feature of most (not all) warp-weighted

weaving was that the weaving started at the top and the wefts were beaten upward.

Might it be possible that retention of warp-weighted looms in Norway (there

seems evidence of such retention) may have produced somewhat distinctive weaves

over those (especially small items like cushion covers) that were made on horizontal

looms?

Just a speculation. I think Sonny's suspicion is that the sources are much deeper

and in truth there are suggestions in these descriptions of complex weave variations

not really explained in these two volumes.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 05-21-2006 12:57 PM:

Turko Scandinavian Connection

Hi Folks

Jahannes Khalter, in his Arts and Crafts of Turkestan, notes that

As documented by tens of thousands of Samanid coins found in Scandanavia, but

also a few scattered ones in Central Europe, Samanid trade, passing via the

Volga basin, reached nearly the whole of europe. The list of export goods made

up by the Arab geographer Mukadasi in the 10th century (Brentjes 1976), is long

and impressive. His (incomplete) list comprises: rugs and prayer rugs from Bukhara

and Samarkand, fine cloths and weavings made from wool, cotton, and silk, soap,

makeup, consecration oil, bows that could only be bent by the strongest men,

swords, armour, stirrups,fittings, saddles,quivers, tents, rasins, sesame, nuts,

honey, sheep, cattle, horses and hawks, iron, sulfer, copper.

Sorry, haven't access to the book at present, so no page #.

Dave

Posted by Sonny_Berntsson on 05-28-2006 09:53 AM:

Hello Mr Hunt

The connections between Scandinavia and The Orient, incl. east Mediterraenan

Sea, were very active between 800 – 1050 . There were both robery and trading

and the Northmen ( the Vikings ) took their ships through the rivers Volga and

Dnjepr for to reach Caspian Sea and Black Sea.

The road through Volga was in control by the Khazars who were leading the trading

between the Islamic countries and East Rome. The area south from the Khazars

“custom-border” was called Serkland by the Vikings. Serkland means “Silk-land”

and the Vikings valued silk the same way as gold.

Clothes of silk had a very high value and to wear them were important. Even

chiefs were burialed with clothes of silk.

By natural there were also ordinary folklore textiles brought back to the North,

and from them the women captured new weaving technics and pattern.

Several tousand Nordic people were in service at the East Rome emperor in Konstantinopel

( Byzans ) during 900 – 1050 . Many soldiers returned to the North after 10

years in duty and they were very rich. We can only guess what they brought back

for their whifes. And we must have in mind that textiles were very high valued

at that time.

In a grave for queen Asa 734 A.D. were found a number of textile fragments,

today the greatest textile treasure in Norway. For example a fragment showing

horses, wagons and humans in a process. All in different weaving technics.

Also other weavings with birds, swasticas and geomitric borders.

Unfortunatuly many textiles were lost as sacrifices in graves until circa 1000

A.D.

Regards

Sonny Berntsson

Akrep Oriental Rug Society, Sweden

Posted by Sonny_Berntsson on 05-28-2006 03:56 PM:

Hello Mr Swan

The technic called “düz zili” (straight zili) in Anatolia has also been common

in Skane

(Sweden) during 18-19th centuries and there it is called “dukagang”.

Another common technic in Anatolia is “cicim”, in Skane called “krabbasnar”.

To tell the age of textiles are allways difficult. The pillow from Norway, showed

in my other reply, is photographed in Historical Museum in Trondheim, Norway.

And the stool (chair) has been in the Jorsala Chathedral, a place for pilgrims

since 1200 A.D.

The stool is dated from 16th century and it is written that the pillow belong

to the stool. And I have no reason not to believe it.

There are several textiles in churches in Scandinavia with the same age but,

as far as I know, not one more example with the typical hooks around the eight-pointed

star.

The colours and pattern gives a more old look than any of the textiles from

18-19th centuries.

But this is more a feeling than an proof.

An image from the Museum in Trondheim......

...showing “rutevav”, a typical pattern from Trondheim-area with eight-pointed

stars, cross, squares and triangles built with steps.

Age: 1800 – 1830.

Where the pattern origins from is impossible to tell but they were common in

Norway during 18-19th centuries.

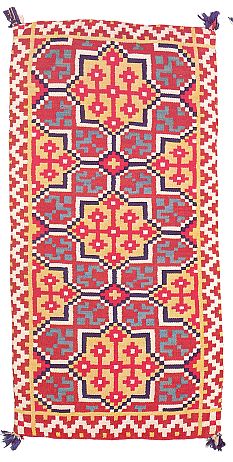

An image from Skane....

...a “jynne” or “agedyna” in rolakan technic.

Age: 1800 – 1850.

Agedyna looks like yastiks in kilim technic from Anatolia. The main pattern

is common in old textiles from Anatolia, weaved in the same technic. Rhombs

with eight-pointed stars linked together with an axle.

Regards

Sonny Berntsson

Akrep Oriental Rug Society, Sweden

)

)