Salon du Tapis d'Orient

The Salon du Tapis d'Orient is a moderated discussion group in the manner of the 19th century salon devoted to oriental rugs and textiles and all aspects of their appreciation. Please include your full name and e-mail address in your posting.

Philadelphia Exhibition of Anatolian Carpets

by R. John Howe

Dear folks –

Dennis Dodds, the Philadelphia collector and architect who is an alumnus of the University of Pennsylvania's graduate urban design program, has curated an exhibition of Anatolian rugs, entitled “Antique Anatolian Carpets: Masterpieces from Philadelphia Area Collections. The exhibition opened recently at Arthur Ross Gallery on the campus of the University of Pennsylvania.

On February 1, 2006, Walter Denny, Professor of Art History at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, gave an associated lecture, “From the Prayer Rug to the Medallion Carpet: Architectural Themes and Functions in Islamic Carpets.” Dilys Winegrad, the director and curator of the Gallery was also instrumental in making this exhibition possible.

I have detailed notes from Denny’s lecture, but will mention only two points he made. First, he questioned whether most Turkish rugs with niches have reference to the place in the mosque toward which worshippers face to prayer (some with stepped arches like some Ladiks may be mirhab references). And he denied that the niche designs in any Persian rugs make such reference. Instead most niche designs refer mostly, he thinks, to the openings into the Islamic Paradise. Secondly, and likely much less importantly, he said (as a gallery note does below) that many octagonal devices in Islamic weavings are references to pools of water. He showed images of some that had waves and in some instances also fish.

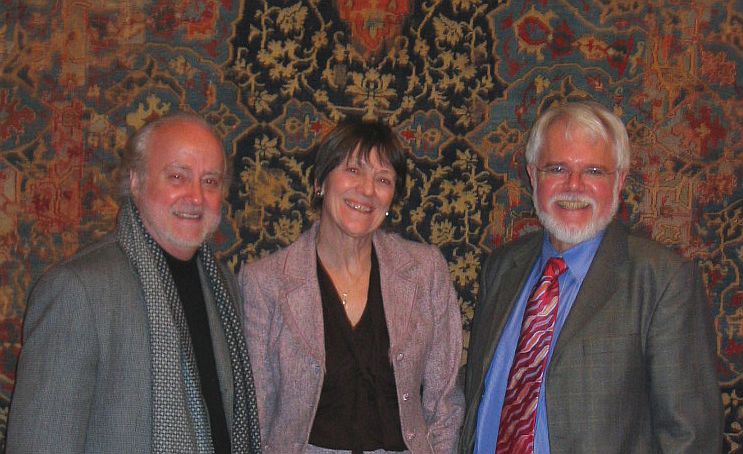

Below, left to right in the photo below are Dennis, Ms. Winegard and Professor Denny in front of an exhibition rug that we will see in full further down.

My wife and I attended this lecture and visited the gallery to see this exhibition. Dennis arranged with the Gallery folks for me to take photos of the rugs in this exhibition. Sara Stewart, a member of the Gallery staff who handles promotion, has provided me with an electronic copy of the gallery labels of the rugs in the exhibition. Dennis wrote the text for these labels.

With Dennis’ permission we are going to show you eight pieces in this exhibition. The pieces below were selected by myself and three of our Turkotek colleagues. There are four pieces about which at least two of the four of us agreed. I also awarded each of us one selection not selected by any of the other three. So we have “consensus” and “utter solitude” reflected in the rugs below.

The pieces are presented in the order of the number of their gallery label. In each case, the rug will be encountered first and the gallery label will be placed beneath it.

Here is a statement that appears at the beginning of this exhibition.

The Use of Water in Islamic Architecture and Garden Design

Gardens, palaces, and mosques incorporated water features in a highly visible way. One such example is the large octagonal basin in the Seljuk Great Mosque and Hospital complex at Divrigi completed in 1229. Islamic beliefs interacted with and defined the architecture of the time and place.

Octagonal water basins drawn on some 13th-century Seljuk and Ayyubid

scrolls indicate the importance of these medieval architectural features in

Islamic cultural history, ritual, and the art related to it. Several of these

paper and parchment certificates in the Turkish and Islamic Art Museum depict

pictorially certain holy

places along the pilgrimage to Mecca, the hajj.* It is reasonable that

these basin-pool images with such strong symbolic value would have entered the

figural vocabulary of artists creating carpet patterns. In some carpets with

this design, the angular outline carries patterns suggestive of water.

Other articles of material culture in carpet design depict the ritualistic association of water as well. Images of water ewers, or ibrik, are frequently woven into the design of rugs that contain architectural arches. These motifs, which provide a graphic reference to ablutions during the prayer ritual, appear in rugs on display in this exhibition.

*See Aksoy, Sule and Millstein, Rachel, “A Collection of Thirteenth-century Illustrated Hajj Certificates,” M. Ugur Derman Festschrift, Istanbul: Sabanci University, 2000 (pp.101-134).

And here are the carpets.

Pile Cushion Cover, yastik, 18th Century; Central Anatolia,

Karapinar

Collection of Ted Mast (ARG 17)

The quatre fleurs design of tulips, roses, hyacinths and

carnations identifies a particular 16th-century development in the creation of

an Ottoman style.

Many of these design elements remained well into the 19th century in

western and central Anatolia, village weaving traditions.

This exemplary yastik joins other weavings in this exhibition thought to have been made in the region. Certain structural and aesthetic characteristics of these pieces are consistent. Here, four large blue tulips are seen in the red spandrels; they appear again inside the aubergine medallion along the vertical axis. Along the horizontal axis are two red rosebuds attached to a red central boss.

The rows of detached arches along the top and bottom of this cushion cover are often seen in yastik design. The side borders carry a series of crescents on a pale blue-green ground. The handsome composition is balanced and the skillful drawing stylized yet refined, indicating an accomplished weaver at work and signifying that this yastik was made with a special purpose or owner in mind.

Pile Rug, ca 1875;

Southwestern Anatolia, Makri

Collection of Leigh A. Marsh (ARG 4)

The best rugs from this region are distinguished by a broad and playful palette. The weaver of this carpet evidently employed an expert dyer to prepare her wool.

Two vertical panels dominate the field, each with small brackets above. Small hyacinth buds attached to the sides of these red and blue reserves express vestiges of an earlier Ottoman heritage. Three outer borders display a series of small serrated leaves and floral blossom attached to a stem, while the lower border shows a rank of well-drawn stars. The weaver began the carpet at this end; after completing the bottom border with one motif, she changed to the leaf design for the two side and upper borders to finish her work.

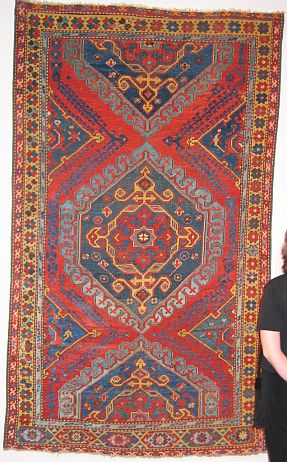

Pile Rug, 18th centuryWestern

Anatolia, Ushak

Collection of Ted Mast (ARG 31)

Court carpets from the Ushak region influenced the design of provincial weavings in many areas of Anatolia. Thus, the weaver of this example took her inspiration from an earlier, large-medallian carpet (e.g. ARG 14). The stylization and simplification of the prototype in this later example typically occurs over time, influenced by the particular circumstances of production.

This carpet, formerly in the historic Deerfield Collection, displays a palette similar to that of the earlier example with its saturated dyes and extensive use of yellow. The central medallion, with its deeply scalloped edges, shows a schematic understanding of the original model. The differences have, however, become pronounced: the graceful round medallion in the 16th-century carpet is rendered as a hexagon, straight faces being more easily woven than curvilinear outlines in unsupervised village conditions. Where the ground of the earlier large-medallion carpet is covered by an intricate network of floral vines, leaves, and flower heads, the red ground here contains an angular string of blue latch hooks and a few detached blossoms.

The central hexagon centers a handsomely drawn octagon filled by a floral device with eight radiating branches-a motif found in 16th-century Turkish models as well as Persian design. The same element survives in a stylized way in the red-ground Dazgir yastik in the exhibition (ARG 3). Gracefully drawn arabesques in yellow append the central octagon. Along the sides of the field, four indented half-medallions are truncated by the border. These diamond medallions are seen as secondary ornaments in the “Star Ushak” carpets of Ottoman weavings dating to the 16th and 17th centuries.

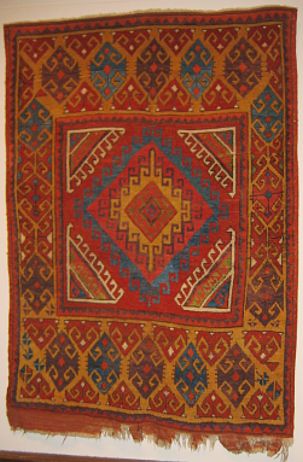

Pile Rug, 1800-50; Central

Anatolia, Cappadocia

Collection of Samy and Sara Rabinovic (ARG 7)

An expression of the Anatolian geometric style is found in this colorful carpet where a square red panel is framed by boldly scaled yellow borders composed of elements found more frequently in flatwoven kilim design. The scale of the wider border at the bottom brings a sense of solidity and proportion to the carpet.

The central panel features a series of concentric diamonds, each elaborately ornamented by reciprocal hooks and dyed in hues typical of the region. The colors—including aubergine, yellow-green, medium blue, and two shades of madder—are similar in range and saturation to those seen in the long rug on the right, which is from the same area (ARG 8). Rather large knots contribute to the angularity and simplicity of the pattern and are typical of many weavings from the region.

Pile Main Carpet, 16th

century; Western Anatolia, Ushak

Collection of John and Ellen Kurtz (ARG 14)

The dominant center medallion of this monumental carpet is filled by an intricate system of split-leaf arabesques that appear in different forms. The edges of the medallion are sharply articulated and two drop pendants are attached. A smaller medallion inside the large ornament is rendered in light blue, a distinction seen in only a few examples of this group.

The design structure of the primary medallion is stylistically linked to the front covers of Ottoman manuscripts dedicated to Sultan Mehmet II in 1465. This and the specific design of the yellow “oak-leaf” motifs that fill the dark indigo background suggest that large medallion Ushaks of this type were woven under the aegis of the Ottoman court in the late 15th century.

The oak-leaf element possibly entered the Ottoman tradition by way of the International Timurid style; it is found in the Baba Nakkash album—a pattern book used prolifically by artists working under royal directives. In 1473, Mehmet II Fatih defeated the Akkoyunlu—White Sheep—a confederation of Turkmen tribes in the Tabriz region of Persia. He afterwards transported several local artists who had worked there to Istanbul.

Carpets of this type, such as several in the al-Sabah Collection in Kuwait, show the primary medallion in a slightly elongated form, a design that is similar to that found on book covers. Here, however, the outline of the central medallion is more rounded.

Here is a little closer look at part of this large piece.

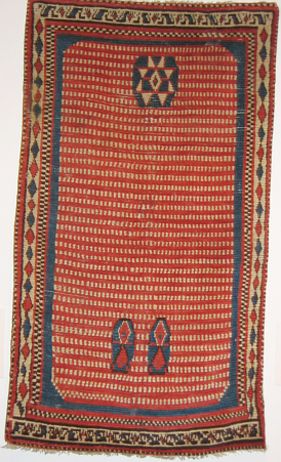

Pile Prayer Rug, 18th Century;

Central Anatolia

Collection of Dr. and Mrs. Charles Beard (ARG 19)

Certain structural and design characteristics found in this unusual rug are consistent with a particular type of weaving from central Anatolia. There are 5-6 wefts between each row of symmetric knots. The spotted pattern is found in several early rugs, including the two well-known “animal pelt” carpets in the Turkish and Islamic Art Museum in Istanbul. It has been suggested that these spots are stylized and reduced versions of the popular chintamani motif that is usually depicted with three spots. A carpet in the Mevlana Museum in Konya, which also displays single spots, shows connected diagonal leaves in the guard borders. This design appears to have influenced—albeit in abstracted form—the upper and lower borders of this enigmatic prayer rug, whose spotted pattern these examples may have inspired. A large eight-pointed star inside a solitary octagon marks the head of the prayer niche.

Other examples showing outlines of two feet at the bottom of the central panel appear in a 17th-century silk embroidered textile in the Topkapi Saray Museum and in two white ground prayer rugs in the TIEM in Istanbul.

Pile Prayer Rug, 18th

century; Central Anatolia

Collection of Ted Mast (ARG 24)

Many rugs in the exhibition display design motifs that traveled freely from court to the countryside, from palaces to the provinces. This village prayer rug expresses many features found in 17th-century Ottoman ateliers operating under royal patronage, yet interprets them in a creative and stylized manner that retains the spirit and inspiration of the earlier, aristocratic prototype.

The border of palmettes, rosettes, serrated leaves, carnations, and hyacinths—all requisite elements in the Ottoman design vocabulary—reflects the convention found in the white ground Ushak prayer rug on display (ARG 23). A broad, madder red niche contains rudimentary columns with a fanciful spray of carnations along it central axis. The graphic stepped arch is surmounted by a crescent form. Two tulips in the white spandrels stand out against sundry spots, carnations, and other miniaturized devices. Tulips appear again in the upper panel issuing from the crenellated parapet—a combination of motifs seen in the Ladik prayer rug (ARG 18) as well as in the distinctive group of “coupled-column” rugs. A nearly identical rug in the Van Ardenne Collection was exhibited at the Rijksmuseum in 1977.

The structure, design, and selection of sparkling dyes suggest that this prayer rug was made in a region of west central Anatolia and was influenced by weavings from Gordes, Ushak, Ladik, and Dazgir.

Slit-weave Tapestry, kilim,

ca 1850; Eastern Anatolia, Erzurum

Collection of Myrna Bloom Marcus (ARG 27)

The central panel of this dramatic kilim is shaped by a steeply sloping arch that terminates at its apex in two appended diamonds. An archaic, branching tree is aligned along the central axis, its angular stems tipped by flower heads. Two large, spiky forms within the niche evoke cypress motifs and are repeated in each spandrel above the arch. A graphic border in golden yellow displays a design frequently found in this group of weavings: a single stiff stem supporting a series of blossoms arranged in pairs. These exhibit a rudimentary segmented style typically used to depict carnations, one of the favored Ottoman flowers.

Woven in the slit-tapestry technique, this piece demonstrates how a slit is created where there is a color change. Many kilims from the region use green as the field color; this is usually achieved by double-dyeing blue and yellow. In this example, areas of yellow-green dye appear at the bottom and at the top of the niche. Most yellow dyes are light-fugitive and fade easily. Over time, dye lots with weaker yellow dyes fade more than others, leaving the indigo blue. It is thus conceivable that the entire field was originally yellow-green.

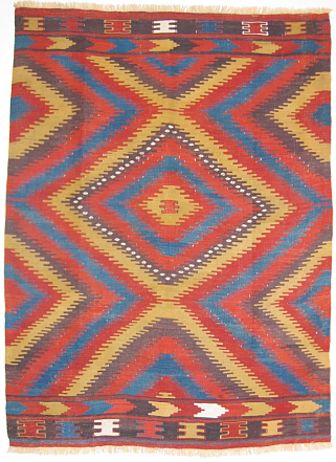

Slit-weave Tapestry, kilim,

ca 1800; Central Anatolia, Konya/Afyon

Private Collection (ARG 29)

The design of this small kilim is composed of concentric diamond medallions, each with serrated edges that elicit attention. This rare design type is known to have come from Afyon, northwest of Konya. Early examples such as this use clear dyes made from the madder root to create three different colors: red, orange, and aubergine purple. The stable yellow dye is particularly glowing and the indigo blue changes from lighter to deeper tones. This abrash, the slight variations in tone that result when the weaver uses different dye batches, lends additional character to the piece. Details of white cotton—the small central ones are brocaded—add a playful punctuation. The design of later weavings remains true to this configuration, but the dyes become somber and dull.

Each end panel displays one band of directional chevrons and one of indented medallions. Because the kilim has a well-proportioned square shape, the absence of side borders allows the design to extend perceptually beyond the edge of the textile, which imparts an extra sense of breadth and movement.

Our thanks again to Dennis, to Ms. Winegrad, and to the staff of the Arthur Ross gallery for making it possible for us to share part of this exhibition with you.

Comments on, and discussion of, the pieces is invited.

Regards,

R. John Howe