Posted by Chuck Wagner on 07-16-2005 03:20 PM:

Clothing & Items of Personal Adornment

Hi all,

To help get things started, and organized, I'll start this

thread with an embroidered belt from southeast Uzbekistan. It was represented to

me as a Tajik piece, but I have no way to verify that. It's very thoroughly

covered with a dense silk chain stitch.

This is obviously not for

day-to-day use; this must have been made for ceremonial purposes, possibly

wedding attire. It has several cute little bugs incorporated into the design;

the back is a piece of abr-dyed ikat silk. The attached pieces are a knife

sheath and a tobacco bag. The belt is 44 in. long; the sheath is 11 in.

long.

Regards,

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 07-16-2005 04:48 PM:

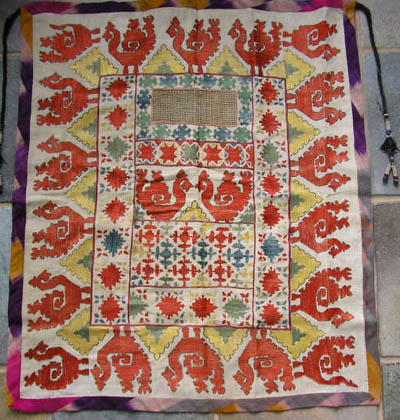

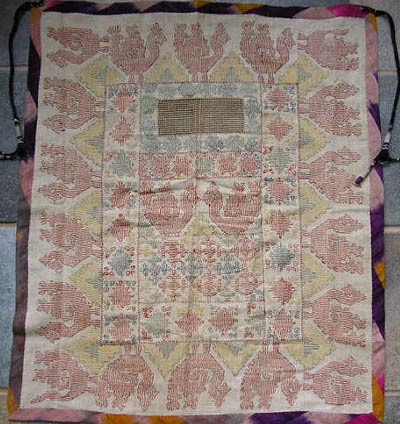

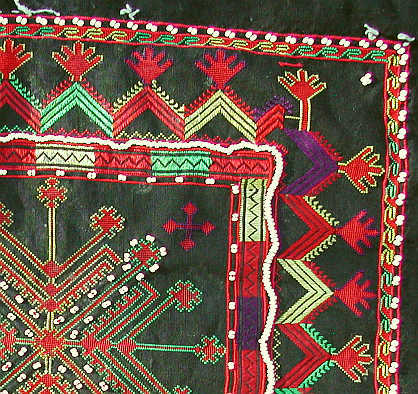

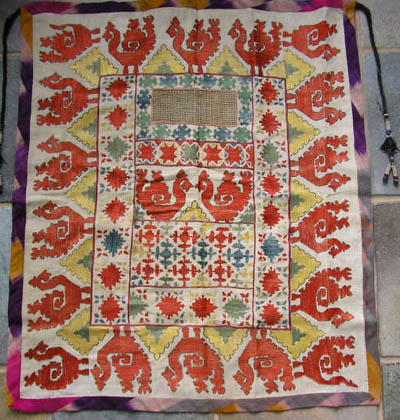

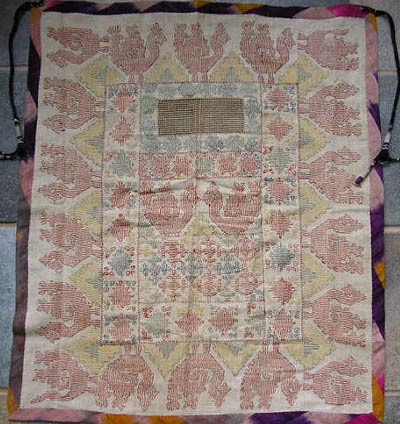

Rooband (Ruband)

Hi all,

In his opening salon, Steve showed us a Tajik wedding veil.

These are called roobands (sometimes: rubands). They were in use by the Tajiks

inhabiting the mountainous area called the Pamirs; if what I read is correct,

these fell out of use in the early 1900's.

Here are some images of

another piece. Note that the base cloth is handspun cotton. The stitch that is

used for this design is quite sparse, and appears to be designed to conserve the

embroidery material. Look at the tedious work that was required to silk-wrap the

cotton to build the mesh for the veil:

All I know about them is

what I have read, and references are not easy to find. To date, these pieces

have been uncommon in western markets. I'll put the text of a writeup from

another site here, and a link to the page if you want to see more of the site;

it's interesting.

The link:

http://www.naison.tj/EN/PRIKL_ISSK/vishivka/the_pamirs.shtml

The

text:

------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Ruband.

Embroidery of the Pamirs and the foothill districts is characterized by a

remarkable diversity of forms. Here it is mainly made on clothes: on shirts and

chemises (along the collar and the vertical cut), women's frontlets-sarban-daks,

the bride's iace-coverlng-ruband, men's and women's belts-kamarbands and

takbands.

Local embroidery has its special individual style with

predominantly geometrical pattern.

Particularly noteworthy are women's

embroidered face - coverings, rubands, used during the wedding ceremony. Their

remarkable coloring and interesting ornaments have attracted attention of

different scholars. Ruband is an ancient nuptial garment of Tajik women living

in the mountains. In our days it is no longer used and can be found only in a

few museums. It is a square or rectangular piece of cotton fabric (75x75 or

90x75 centimeters) covered by embroidered ornaments. In the upper part there is

a small rectangular opening for the eyes with a net made from white silk

threads. The two upper corners have long colored strings with tassels for

fastening ruband on the head (usually it is worn over the head-dress). The edges

are trimmed with a dark plaited braid. The cloth is embroidered with silk

threads in a compact flat stitch, so that the smooth lustrous surface of the

ornament makes its flatness still more evident. It may be noted that this

technique is very economical, as threads are not used on the reverse side of the

cloth. The scheme of ornament is determined by the rectangular form of ruband.

It consists of a number of rectangles inscribed into one another. The one in the

centre, having a more elongated form than the others, is divided into several

horizontal strips, with the netted opening for the eyes in the upper strip. The

ornamental motifs of rubands are not particularly diverse. They include stylized

trees, triangles, rhombs, geo-metrically outlined flowers, birds, rosettes,

etc.

The ornamentation of ruband is an interesting product of the popular

art. N. A. Kislyakov appraised it as follows: "As far as we know, neither

nomadic or semi nomadic peoples nor the settled population of Central Asia, Iran

and Afghanistan which used the woman's face-covering - parandja or chadra, have

possessed or possess now so richly ornamented wedding face-covering as ruband of

the mountain Tajik. Modern Tajik embroidery adheres to the traditions of the

late 19-th and the early 20-th centuries. The handicraftsmen continue to produce

things which are still used in everyday life or connected with the living

national customs. On the other hand, many types of embroidery, as, for instance,

zardevor and ruband, have gradually gone out of use. The high artistic and

aesthetic standards of popular embroidery make it possible to use it for

decoration of the modern interior and ornamentation of clothes. The traditional

methods and techniques of popular embroidery are successfully used by many

factories working in the Republic.

The bulk of the material published in

the album is based on the museum funds. A certain part of it was gathered by the

author during expeditions in Tajikistan and the Tajik-populated districts of

Uzbekistan. The drawings of embroideries were made from life, that is, directly

in the interior where each embroidery has its definite place and is set off by

the national decor of the room. In our opinion, this method has some advantages,

because an embroidered piece in its natural environment enables you to grasp

better the subtleties of this specific art, to feel its nuances and reproduce

all this with greater accuracy. In gathering the "field" material attention was

paid not only to big decorative works but also to very small pieces ornamenting

clothes and things of domestic use. An analysis of the collected material,

showed that small embroidery preserves the local features of the place where it

was produced much better than embroideries of a bigger size. A considerable body

of material was gathered in the main centres of the industry and their environs.

Some other districts, however, are represented by a comparatively small amount

of material, and there are some localities which have not yet been surveyed. The

samples reproduced in the album give a rather comprehensive picture of the Tajik

art of embroidery and illustrate its main peculiarities. A greater part of this

material has not been published before. The author is greatly indebted to Doctor

of Arts N. A. Nurdjanov, Master of Arts N. A. Belinskaya and Master of Arts N.

N. Ershov whose advice and cooperation were most valuable in the preparation of

this

volume.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Regards,

Chuck

Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by R. John_Howe on 07-17-2005 02:35 AM:

Hi Chuck -

Good stuff in your post above.

I quite like the

belt, knife sheath, tobacco pouch set. Nice greens. Do I see evidence of Chinese

influence? Cloud bands, etc. Don't think I've noticed such usage in things

attributed to Tajiks.

I really know nothing about the real tribal

distinctions in this area but have run into "national character" type

descriptions of some of these ethnic groups. As I recall, Tajiks are often

described as, urban, Persian speaking. Tajiks are often in such literature

compared rather unfavorably to Uzbeks. Do we know if these pieces were woven by

more rural Tajiks?

I have also sometimes wondered about the border design

in this veil. Could it be representational? Perhaps some kind of ornamented

rooster?

Such veils seem rather frequent in recent years but are

admittedly attractive.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 07-24-2005 08:32 AM:

Hi John,

A problem with many of these pieces is lack of provenance, so

we can only rarely "know" much about them. As you have pointed out, most

attributions seem to be regional rather than tribal. I don't think the Kirghiz

& Tajik tribes have had nearly the studious attention that the Turkomen

tribes have received. Only a few westerners have put much effort into the Uzbek

tribes, largely the Lakai & Kungrad, although Kungrad is a regional term as

well as a tribal term.

And, I suppose that with the large amount of older

textile materials available in the former Soviet Union, there may be a certain

amount of "reproduction" going on that might be hard to identify, particularly

the assembly of a single piece from fragments of several older pieces.

In

the particular case of the rooband, I have been told by one person that

reproductions are being made in Tashkent. There is no way for me to verify this.

Such an operation would have to have access to handspun and hand woven cotton

cloth (karbos), and I have doubts regarding much recent production of such

material.

Roobands are said to come from the Tajik Pamirs region, which

holds both urban and rural population centers, which is not really very

diagnostic. It's like saying something comes from Appalachia. It's probably

rural or rustic, but could easily have come from a large town.

Regarding

the designs, it's my understanding that the bird figures are a "male potency"

thing and the florals are a "female fertility" thing. However, other than a few

Russian ethnographers, I doubt that there is anyone alive today that has a valid

explanation for the designs.

I am very fond of the belt. Janet Harvey (in

Traditional Textiles of Central Asia) notes that it is common for a bride to

make very special items for the groom, and she mentions belts specifically. So,

given the high quality of work and festive appearance, I would guess it's

probably a dowry item.

It wouldn't surprise me to find Chinese design

elements in Tajik or Kyrgyz items. They, like eastern Uzbekistan, are regions

that were conquered and held by the Mongols for centuries, and are in such close

proximity to China that trade inspired design influence must certainly have

found its way into region. You'll see that in a suzani I'll be posting a little

later.

Regards,

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 07-24-2005 09:13 AM:

Hi Chuck,

I love your belt. But you’ll need a knife for that

sheath.

Something like the ones shown in this thread:

http://www.iranian.com/Arts/2001/March/Tajik/knife.html

or,

better like one of these:

http://www.vikingsword.com/vb/showthread.php?t=34&highlight=Indo-Persian+knife+comment

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 08-10-2005 11:58 AM:

Hi all,

First, Filiberto, those are some business-oriented knives

behind that Tajik knifesmith. Very utilitarian, and with a shape that is just

unusual enough so that I wonder if it is notable as a regional marker.

I

had an opportunity (which is different from having the money) to buy a gorgeous

ceremonial Uzbek knife several years ago: calligraphy cut into the blade,

engraved, very nice. But too expensive.

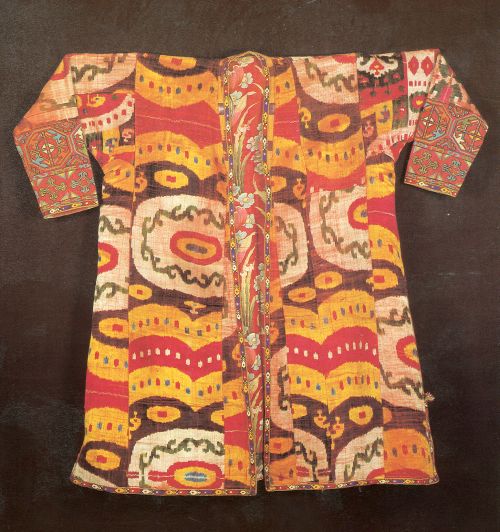

Now, still undaunted, I'll move

on to a topic that must be included in any presentation of Central Asian silk

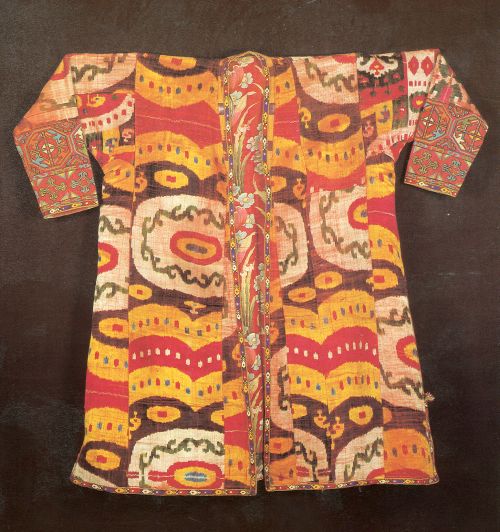

textiles: baghmal, or, silk velvet ikat.

While not exactly rare in the

market, it is uncommon and generally pricey. The most expensive, and most

beautiful, baghmal pieces are the intact 19th century overcoats (or better,

mantles) like the one shown in a journal writeup by Wendel from a while

back:

or this

one, from Kalter's "Arts and Crafts of Turkestan", which also has some great

embroidery on the sleeves:

Probably the next most common manifestation is the mounted

rectangular panel, most likely cut from older overcoats that were otherwise

unsalvageable. Again, an example from Wendel's journal piece:

The other way baghmal shows up is

as smaller articles of clothing either purpose-made, or made from scraps of

larger items, such as hats and caps. Like this one, with a long tail that hangs

down the back of the wearer:

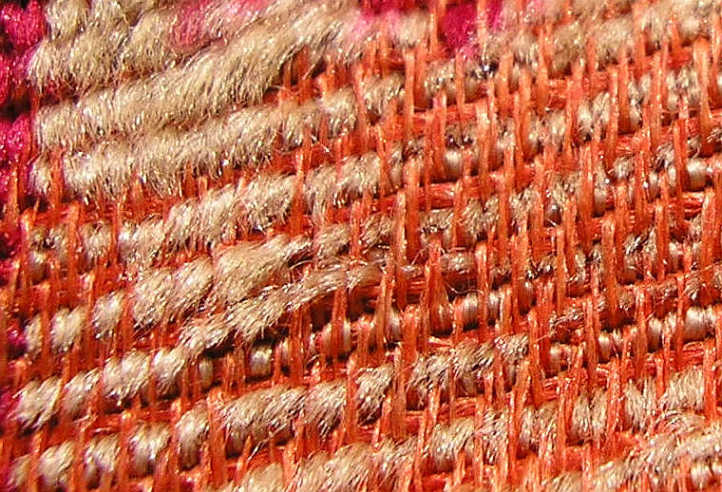

Before looking more

closely, I think it would be useful to have a quick review of how baghmal is

made (which is easy, because there's very little documentation). The best

writeup I've been able to find is in Janice Harvey's "Traditional Textiles of

Central Asia". She writes "For the manufacture a complex threading of a double

warp was necessary. A foundation warp of plain orange or pink silk threads was

threaded alternately with an ikat-dyed warp several times the length of the

plain warp and set on a separate beam. As the weaving with a cotton weft

progressed, the ikat-dyed warp was raised separately over grooved wires inserted

on alternate picks. After a section was woven, a sharp blade was run down the

grooves, leaving the velvet pile with its clear ikat pattern held by the

alternate pick of cotton weft."

I haven't been able to find any images of

Uzbek baghmal production facilities. However, in Italy, there is a facility in

Firenze called the Fondazione Arte della Seta Lisio, which seeks to "ensure the

survival of the finest hand-weaving techniques, especially of the velvets and

brocades of the Italian Renaissance". This includes the manufacture of handmade

silk velvet. While not quite the same as silk ikat, the process is similar. The

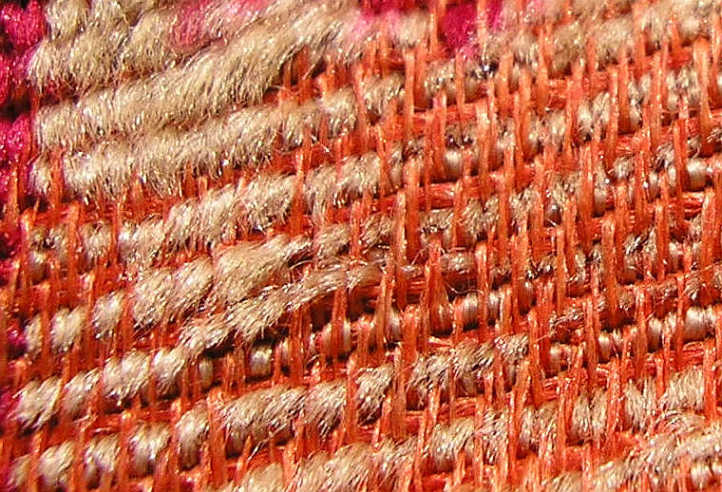

following diagram and image, of a worker slitting the velvet pile, are from

their website (http://www.fondazionelisio.org/in00e.htm ):

Now, we can look

a little closer at the cap, and enjoy this sumptuous and complicated bit of

textile:

In these last two images we can see the structure up close,

and in the worn areas, see both the cut and uncut loops of the ikat silk

warp:

It

is my understanding that there is now an effort underway in Uzbekistan to

resurrect the production of baghmal, the old fashioned way. If this effort is

successful, collectors will have to find a way to discriminate between new and

old pieces. Here's some evidence; as part of UNESCOs worldwide cultural

activities, it awarded the following Crafts prize:

Second Prize of US

3,000 dollars to Mr Rasuljon Mirzaakhmedov of Uzbekistan for reviving the art of

weaving chenille – “Bakhmal”, a traditional octahedron ornament using the ikat

technique.

Regards,

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Mishra Jaina on 08-24-2005 10:58 AM:

Hi

Here is a pair of shoes / booties that appears to be from the same

area.

They are the size of my palm. Found them in an old shop in

Beijing.

Any comments about its origins.

Regards

Jaina

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 08-24-2005 07:54 PM:

Kaffiristan

Hi all,

First, Jaina, those look like Western China/East Turkestan or

Mongol work to me. Very fine work on such small pieces.

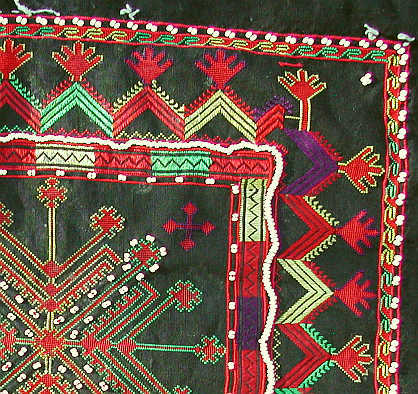

Also, to fill out

the Central Asian pieces a little more, I'll show you an embroidered womans

cloak from what is now called Nuristan (Land of The Enlightened) or sometimes,

Kohistan. It's a region that encompasses portions of far northeast Afghanistan

and far northwest Pakistan. This area was previously referred to as Kaffiristan

(Land of the Infidels), and may well represent the last conquest in the

expansion of the Islamic world; it was forcibly converted from animism to Islam

in the mid-1890s by AbdurRahman Khan.

This is a modern piece, probably

from the 1960's or so. It's about 8 feet long and 5 feet high. All the

embroidery work is done by hand.

There is a metal zipper

along the bottom edge that serves no functional purpose; such decoration is

common in Afghan and Pakistani work:

Some of the work is

exceptionally fine; this area measures about 8 x 8 inches:

And for the unbelievers out

there  , here's an image of the

back of the piece, showing that it is hand work:

, here's an image of the

back of the piece, showing that it is hand work:

;

;

I have several images of a

tunic from the same region somewhere in the Turkotek archives; if I can't find

the reference I'll repost them. It's also got some very nice

handiwork.

Regards,

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

, here's an image of the

back of the piece, showing that it is hand work:

, here's an image of the

back of the piece, showing that it is hand work: ;

;