Posted by Steve Price on 05-22-2005 01:30 PM:

Why do we care whether dyes are natural?

Hi Vincent

You raise a number of interesting questions, but I'd like

to raise yet another: Why do we care whether colors come from natural dyes?

I think the most common answer from ruggies would be that natural dyes

are more beautiful than synthetics, and many believe that this is an intrinsic

(as opposed to a learned) preference. I think it is very unlikely to be

intrinsic. In fact, in most weaving cultures synthetic dyes are used

preferentially with items made for use within their community. Much of what they

prefer is what many of us call garish. How could that be, if natural colors are

intrinsically preferable?

I think the answer is fairly straightforward:

ruggies collect antique rugs because they are antique. They don't want

reproductions or copies, no matter how well done. One fairly easy way to

identify an antique rug is by the colors. So, we have learned to identify colors

derived from natural dyes with a reasonable level of certainty, and have learned

to consider such colors beautiful simply because they are associated with

age.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-22-2005 07:04 PM:

Hi Steve,

Right on target.

I don't agree with you. I think it's an

intrinsic, distinguishing quality and maybe this salon will learn us how to

differentiate on a more solid basis.

We'll see where it leads us.

Why

do most weaving cultures prefer "garish" colors?

If garish colors are the

result of synthetic dyes it could be a learned preference as well.

The

chemical industry teached them: "Why bother? These dyes are easy, cheap and red

is red, pink is pink etc.!"

So I don't know if we can be sure the weaving

cultures liked the garish colors better.

If we look at the Tabriz

(pink/purple/turqoise) production......the answer is all there?

The old dye

recipes are quickly forgotten and that's the end of it.

You say:

"One

fairly easy way to identify an antique rug is by the colors. So, we have learned

to identify colors derived

from natural dyes with a reasonable level of

certainty, and have learned to consider such colors beautiful simply because

they are associated with age."

I would like to find out how other ruggies

do that.......... with a reasonable level of certainty and no chemical

testing.

What do these ruggies think they see?

Best

regards,

Vincent

Posted by Richard Farber on 05-22-2005 07:16 PM:

dear all

i think that the "impurities" inherent in natural dyeing are

what we find appealing. in natural dyeing there are constant fluxuations in the

intensity of the color AND constant changes in the frequency -- that is in the

color itself . . which are often not seen as abrash but as the natural in the

natural color.

early synthetic colors tended to be too constant -- that

is lacking the minute changes of intensity and frequency

early

synthesized sound was too pure and easily recognized . this has changed

considerably in the last years and i image also in the dying industry.

it

is after midnight here . . i will think about this and try again

tomorrow

r

Posted by Steve Price on 05-22-2005 10:04 PM:

Hi Vincent

To return to the matter of whether preference for natural

dyes is learned or innate, let me offer an observation:

I prefer rugs and

related textiles with colors derived from natural dyes, but for most other

things, I'm perfectly happy with colors that are made with synthetics. My

clothing, household furnishings, personal accessories, automobile - you name it.

Not only that, I see the same thing in every other collector of antique textiles

that I know. The only things for which they prefer colors made from natural dyes

is in their antique textiles.

The hypothesis that preference for natural

dye colors is innate seems to me to encounter real difficulty here. The

preference applies to antique rugs and collectible textiles, but only to those

things. For everything else, synthetic colors are not only acceptable, they're

preferred. I would take this as pretty compelling evidence that the preference

for natural dyes is a learned condition, and that the learning isn't even

generalized beyond a particular class of items. The simplest explanation seems

to me to be not that we like antique textiles because they use natural dyes or

that such dyes are instinctively appealing, but that we like natural dyes

because they are in antique textiles.

Make no mistake - I much prefer

palettes of natural dyes in my rugs and textiles, and could run off a list of

the things that I like about them. But I think I learned to like them, and would

have found them of little interest if they were not associated with antique

textiles.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Michael_Wendorf on 05-22-2005 10:56 PM:

Why do I Care? Tradition.

Dear Readers:

A certain fiddler I know of, summed up why I care about

and prefer natural dyes - tradition. The use of natural dyes/colors is older

than the rugs we collect and far older than the industrial age and the advent of

I.G. Farben and Bayer, it is most likely the result of an evolution that began

with the inherent variation and range of color found naturally in goat hair and

then wool and the slow experimentation with roots and plants and even bugs found

locally in cold and warm dye baths. Natural dyes represent and possibly reflect

a tradition, like weaving, with its roots in antiquity. I look for the same

tradition in the rugs and textiles I try to collect.

Regards,

Michael

Posted by James Blanchard on 05-23-2005 12:46 AM:

Dye stuff, or wool?

Hi all,

I am no expert in distinguishing between natural and synthetic

dyes, especially in many of the red shades. But I know what I like. For me, it

is not only the colours, but also the quality of the wool that makes the

difference in the "look" of a rug. Some rugs just have a "glow" to them, which I

think derives not just from the type of dye, but also the way in which the wool

takes the dye. For example, I have a few rugs that make my other rugs pale in

comparison, even if they look pretty good by themselves. Some of these "glowing"

rugs almost certainly have natural dyes (like an old Tekke and a not-so-old

Ersari). But I also have a not-so-old Yomut (Dyrnak gul) in the same "league"

when it comes to wool quality and glow, but which I think has a few synthetic

colours as well. All of them put the "shiny" new products from Pakistan and

India to shame, so "glow" is different than "shine".

I also have an old

Jaf Kurd bag that almost certainly has all natural dyes, but it is a bit

"lifeless" due to less lustrous wool, so not as aesthetically pleasing to

me.

Cheers,

James.

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-23-2005 06:25 AM:

What Michael indicates as “tradition” was more often identified as the

“ethnographic” aspect in similar discussions on Turkotek. I guess the word

“ethnographic” must be a little out of fashion nowadays…  In any case the meaning is still the

same: the assumption that a rug was made without any intervention and material

from our industrialized world – like synthetic colors and machine-spun wool.

In any case the meaning is still the

same: the assumption that a rug was made without any intervention and material

from our industrialized world – like synthetic colors and machine-spun wool.

Without disagreeing, I would say that “tradition” and also the

“antiqueness” mentioned by Steve are intellectual factors.

Now, if I

understand well, Vincent’s aim is more on the physiological - NOT intellectual -

qualities that make us appreciate certain colors and make us think they are

natural… And the “basic standards by which you try to distinguish chemical from

natural dyes.”

I think we like colors when they are “alive” and

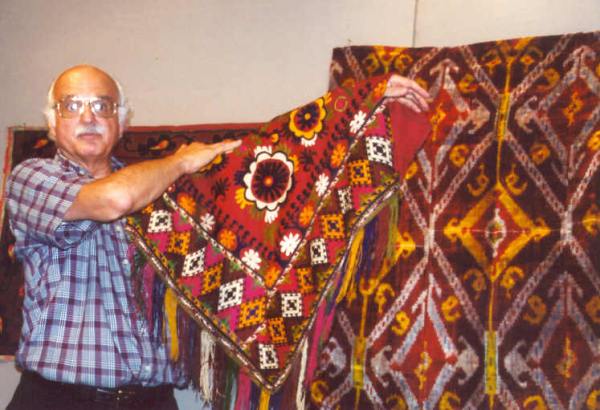

vibrating. Like these:

Photos posted by Chuck Wagner in the discussion Dyes and

Ethnographic Value http://www.turkotek.com/misc_00004/discussion.htm

Do

you like those dyes? I do. Fact is, we don’t know for sure if they are natural

or synthetic. The rugs depicted are modern, so they should be more likely

synthetic.

Of course, a very important factor in dyeing, besides the kind

of dyes, is the ability of the dyer in using them and the quality of the wool.

Good quality hand-spun (hence lanolin rich) wool takes the color in a more

lively, non-uniform way and tends to develop a lovely patina with the time.

Machine-spun wool has less lanoline, is more uniform in the yarn diameter, and

takes the dye more “flatly”.

On the other hand a bad synthetic dye looks

awful even in old rugs with good wool…

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Steve Price on 05-23-2005 07:42 AM:

Hi Folks

There are at least two questions that have become intertwined

in this thread. I'd like to just spend a moment listing them before we get

tangled any further:

1. How did our (us = rug collectors) preference for

colors derived from natural dyes arise? Is it innate or learned? This is the

question with which I initiated this thread and to which Vincent and Michael

replied.

2. What is it about natural dye colors that we find more attractive

than synthetic colors? This question is addressed, for example, in Filiberto's

post immediately before this one and in James' post. It's a very different

question, and probably ought to have a thread devoted to it (maybe more than

one).

Michael's point - that the natural dyes are a connection to

ethnographic traditions and appeal for that reason - seems to me to be pretty

similar (but not identical) to my belief that they appeal to us because they are

associated with antiques. I think his is closer to being correct: it accounts

for the fact that the natural color palettes that we prefer are

tradition-specific. For instance, we find the natural palette used by the

Qashqa'i very attractive on Qashqa'i textiles. The same palette on, say, a Tekke

piece would be unattractive to most of us.

Regards,

Steve

Price

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-23-2005 08:43 AM:

Dear folks -

There are several things in this thread to which I'm

tempted to respond but here let me just do so with regard to Steve's initial

question "Why do we care if the dyes in the pieces we collect are

natural?"

My list of answers to this question includes:

Because

we've socialized into believing that the colors produced by natural dyes are in

some sense more attractive than those produced by synthetic ones (a point Steve

has made). I'm going to make a separate post about something that seems to me a

permutation of this aspect of this subject.

Because they can serve as

markers in attempts at attribution (for example the Saryks produced some

wonderful oranges that seem distinctive to them).

Because (since we tend

to think also that "older" is "better") many of us want to say about our pieces

"possibly before 1850," a sentence that can't be said about something that has a

synthetic dye in it.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by George Potter on 05-23-2005 09:24 AM:

Dear all,

I think the word ‘natural’ is used too often to mean ‘good’

in all sorts of circumstances, probably also when it comes to dyes. I cannot

tell natural and synthetic dyes apart if it is not obvious, like a screaming

pink or green. As some natural dyes are molecularly identical to synthetic ones,

it is the dyeing technique that makes a difference. I am sure the results can be

reversed, so that natural dyes can be made to look synthetic and vice versa. To

me, antique rugs look and feel better because the quality of the workmanship is

superior, no matter what dyes were used.

Regards,

George

Potter

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-23-2005 11:21 AM:

Hi Steve,

1. How did our (us = rug collectors) preference for

colors derived from natural dyes arise? Is it innate or learned?

I

think it’s learned. Or, to put it in a different way, taste for colors is

culture-related and subject to fashion and changes.

Example: a century

ago Europeans used a much more restricted palette in their clothing than

nowadays. And modern Europeans do not use the same range of colors as, say,

Nigerians or Indonesians do in their traditional garments.

Ruggies are

more conservative when it comes to colors on rugs, but the people producing them

quickly adapted to new palettes offered by synthetic dyes.

Then, the

criterion used by rugs collectors seems to change when we go to textiles like

Turkmen chyrpys or Uzbek Embroideries.

I remember a Show and Tell thread

where Steve showed Western and central Asian embroideries (I still have the

pictures).

Most of them had very bright colors and some sported glowing hot

pinks. Nobody objected to them.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-23-2005 11:28 AM:

Hi Steve,

1. How did our (us = rug collectors) preference for

colors derived from natural dyes arise? Is it innate or learned?

I

think it’s learned. Or, to put it in a different way, taste for colors is

culture-related and subject to fashion and changes.

Example: a century

ago Europeans used a much more restricted palette in their clothing than

nowadays. And modern Europeans do not use the same range of colors as, say,

Nigerians or Indonesians do in their traditional garments.

Ruggies are

more conservative when it comes to colors on rugs, but the people producing rugs

quickly adapted to new palettes offered by synthetic dyes.

Then, the

criterion used by rugs collectors seems to change when we go to textiles like

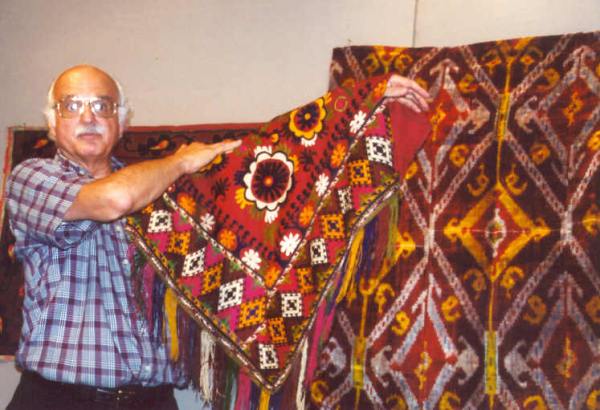

Turkmen chyrpys or Uzbek Embroideries.

I remember a Show and Tell thread

where you showed Western and central Asian embroideries.

Most of them had

very bright colors and some sported glowing hot pinks.

Like this

one:

Nobody

objected to them.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Patricia Jansma on 05-23-2005 07:29 PM:

Dear All,

When I look at an hand made piece of art or applied art I

search for art, originality / character, beauty, and something that touches me.

The question of synthetic or natural is quite unimportant, as I agree with what

mr. John Howe says - some natural colors can be dull and synthetic colors very

goodlooking.

I think that often 'natural' is associated with antique,

authentic, 'used' - full of the emotions / traditions / life of a culture. A

used 'authentic' piece can sometimes be like a time (and place) machine to a

life different from ours but with a great sense of beauty that we recognize.

I think authenticity and art are not a question of color (nor necesarily

antiquity), and that those who discard a piece because the color might be

synthetic are doing themselves short A bit like fixating on the paint instead of

the painting.

Something else, as a trainee in the field of appraising

art and antiques I see a lot of disagreeing among appraisers and antique dealers

about age, authenticity etc. People with a lot of experience in a field (old

specialists) obviously have an advantage over younger generalists. But I think

there is no such thing as 'without error', even for specialists. Maybe just less

mistakes.

I am very interested to see the outcome of a test such as

Steve proposed, testing the 'experienced eye test'.

Kind regards,

Patricia Jansma

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-23-2005 10:14 PM:

The child in us

Steve,

Maybe our eyes pass on more info than our brains can handle at

first sight. I noticed that

most of the time I need a little time to absorb

colors, combinations of colors and only

when I let it rest for a while and

remember the impression the colors gave me,

I'm able to form an opinion.

Never at first sight.

Sometimes a rug gets better, sometimes a rug gets

worse.

A read that children see a color, but the overwhelming impression is

the opposite color in the color spectrum.

So a red color makes a child more

at ease?

Different with modern art. All synthetic dyes.

First

impression is the impression. I like it at first sight and I like it the next

morning.

Think synthetic dyes do not tickle the opposite colors in my

brain?

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Marvin Amstey on 05-24-2005 05:04 PM:

Ms Jansma makes a good point: the experts can be wrong. I recall reading the

intro to a large tome about the British Museum's jade collection at a time when

I thought it would be interesting to collect this hardstone. The author made it

very clear that only 11 pieces in the collection had ever been tested as jade.

He was also convinced that some of the pieces probably were not jade. However,

the beauty and antiquity still was present. So, if the British museum experts

err, I'm sure that we do frequently when it comes to colors and ages of rugs.

And as has been said time after time: it's all in the eye of the beholder. Each

of us simply has to develop the confidence to acquire a rug because of what

he/she thinks, not what someone else thinks.

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-24-2005 09:40 PM:

Hi all,

Yes the experts can be wrong.

Never mind the

experts.

It's all about you and me. If a rug's up for sale, and it has some

age, in 99% of the cases we hear: "All natural dyes".

Nowadays, every kilim

from Iran is all natural dyes.

All Pakistan Zieglers are all natural

dyes.

So, my question remains!

In what rug do you see natural

dyes.

How do you see that. What brings you to this conclusion?

All

that has been said on this board, up to this moment looks a lot like the

everyday bla, bla, bla I hear everyday. But I know, that the moment an old piece

is put in front of a "specialist" by the person who says "Never mind", that

person will be very disappointed in THE SPECIALIST if he/she says all the colors

could be synthetic and even the corroded parts. The result can be: The

specialist is foolish.

It's a simple question!

What do you see? How

does your brain work?

Is a green natural because you see blue and yellow? Is

a plain green never natural?

Can a faded dye be natural?

Is a corrosive

dye natural? etc.etc.etc.

Every color must have its story for each of

us.

So let's make a start

Orange is already on air. Blue is already on

air. (Never mind the images I posted. I just like playing with details and the

images keep it airy?)

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-25-2005 04:12 AM:

Hi Vincent,

Is a green natural because you see blue and

yellow?

Most likely. Which doesn’t mean always. Let’s say probably. But I

am no expert, so I must add "IMHO".

Is a plain green never

natural?

Ditto.

Can a faded dye be natural?

Yes. A badly

applied or bad quality natural dye can fade.

Is a corrosive dye

natural?

Not necessarily. See “Use of Certain Rug Dyes as Markers of Age

of Oriental Rugs” by Paul Mushak (www.rugreview.com/5dyes.htm):

“For one thing, synthetic

blacks and dark browns are not without their own corrosion potential for wool.

The presence of corrosion is therefore not necessarily diagnostic, per se, in

the absence of laboratory testing. In my last article in ORR on identifying

synthetic dyes in Istanbuli pieces ca. 1900 (15/1, pp. 27-33), I noted

blue-black and black areas that were all comprised of acid dyes on brown wool.

These areas in the main rug under discussion (Rug 1) showed obvious and

selective wearing away due to the combinations of harsh synthetic dyes and acid

treatment of yarn prior to dyeing. Purely on the basis of differential pile

loss, one might erroneously conclude that these black areas had natural

iron-mordanted tannin dyes.”

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by James Blanchard on 05-26-2005 01:54 AM:

It seems that age assessment is at least one significant factor that makes

determining whether dyes are natural or synthetic consequential. So here is a

novice (if not novel) question....

What are some clear examples of types

of rugs or textiles where age assessment hinges on knowing whether or not the

dyes are natural? In other words, how often does "knowing the dye" add to the

assessment of age beyond materials, structure, design, etc. Can we also specify

those types of pieces for which knowing the dye is most crucial for assessing

age?

James

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-26-2005 08:43 AM:

James -

I fear it's not that easy since both the character of the dyes

and the approximate age of a given piece are both difficult to determine and

most estimates are made on the basis of clusters of indicators.

Still

experts sometimes seem to work in the way your question suggests. I own a six

gul Tekke torba and a 12 gul Ersari chuval both of which the late Turkmen

expert, Robert Pinner estimated to have been made "before 1850."

When I

asked why he thought that he said "Because of the dyes." I think he may have

been saying mostly that he didn't see any colors that looked suspicious to him

and that pieces with all natural dyes were more likely to have been woven before

1850 than after.

Some might argue that my two pieces might well have been

woven in the third quarter of the 19th century, since synthetic dyes would need

some time (but not much) to reach weavers in Turkmen country after the

German/Swiss discovery of them in approximately 1860.

But I think that's

how some experts use their evaluations of dyes in their estimates of

age.

There is, though, an article at the back of the Mackie-Thompson

catalog "Turkmen" in which Mark Whiting discussed dyes in Turkmen weavings.

Whiting says that the early aniline dyes were used by Persians and in

the Caucasus but are "almost absent" from Turkmen pieces tested. But the "azo"

dyes invented in 1875-78 and probably on the Euopean market by 1880 are found

far more frequently in Turkmen weavings. Whiting says that Ponceau 2R has been

found in the weavings of every Turkmen tribe. Whiting proposes a dating scheme

for Turkmen weaving base on dyes. He says his dates are "guesses.'

Period 1 Ends 1840-60 Natural dyes including some lac and

cochineal

Period 2 Begins 1840-60 and ends 1875-85 Dyes still

natural

Period 3 Begins 1875-85 and ends 1890-95 Small amounts of

fuschine are found occasinally

Period 4 Begins 1890-95 and ends 1900-10

Azo dyes used usually in less than one third of area of weaving

Period 5

Begins 1900-10 and ends 1918-1925 Azo dyes used extensively

Period 6

Begins 1918-1925 Natural dyes disappear.

Whiting also referred to a

gradual deterioration in the use of traditional tribal designs during these

various periods.

Pinner could also have been thinking of Whiting's work,

since they were friends.

Pinner, by the way, characterized most of our

estimates of age as based on "conventions" rather than pinned down by real

knowledge. He used such conventions in his own estimates, but would not have

claimed that they were very solidly basis on real

evidence.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 05-26-2005 08:48 AM:

Hi James

Attributing an age to a piece is hardly ever anything more

than a statement of the probability that it was woven during a certain window in

time. Knowing about the dyes is one of the factors in determining what that

window is.

If a rug contains at least one synthetic dye (and if we can be

sure that it is original, not part of a restored area), it cannot have

been made prior to 1858 and is very unlikely to have been made prior to 1880.

If the dyes are all natural, unless it's Belouch, it's very likely to

have been made before 1900.

If it contains all natural dyes except a

violet faded to white or gray, it's very likely to have been made between 1890

and 1925.

If it contains many tip-faded synthetic dyes, it probably

dates to some time between about 1920 and 1940.

None of this allows a

highly specific date attribution to be made with near certainty, but it includes

some pretty good head starts and can narrow things down quite a bit even in the

absence of other information.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 05-26-2005 09:26 AM:

Hi James,

The assessment of age through, as you put it, only “knowing

the dye” is on its own without any sense. There are some exceptions to it as

there is sulfonic-green, a grayish green made from indigo and sulfonic-acid,

which use started early 19th. cent. in Turkey or an aubergine color which, will

never be found in Caucasian rugs after ± 1900.

However, in general, it is

the whole context of the other parameters ( design, structure, material, size,

quality of wool/colors, origin ) which will give the colors its final weight in

the process of assessment. Each of these other qualities are even important to

it and they are also interacted which each other.

Of course one can value

each parameter on its own merits, but for a final assessment of age, you have to

look always at the complete picture.

One parameter I didn’t mention yet is

“rarity”. This is the one where the “experienced eye” comes in.

If one has

seen for years and years all kind of rugs, there will automaticly grow an

understanding of scarcity of certain types, and consequently also of the

parameters making it a rare type.

This is a very important factor in the

learning process, but it takes time and a curious mind.

Best

regards,

Rob

Posted by James Blanchard on 05-26-2005 01:41 PM:

Hi all,

Thanks for the additional information regarding dyes and age

attribution, but I still think that more clarity is still necessary for those of

us who are novice rug buyers.

First, I am intrigued by John's account.

The assessment of "all natural dyes" conferred a date estimate of "pre-1850",

yet as I understand the "dye period" construct, natural dyes were widely used

much beyond that, and even exclusively during "Period 2" which extends to 1885.

So how confident can one be in dating to pre-1850 based almost exclusively on

the presence of all natural dyes?

So what is the message for a novice

rug buyer? If I am considering a 6 gul Tekke torba that I am persuaded has all

natural dyes, can I assume that it is pre-1850? Not based on the "dye period"

guide, so I must look for other clues, as I must assume Pinner and John have

done.

If the "dye criterion" applies mostly to several "inflection

points" or "windows" as described by Steve, and these tend to be in the late

part of the 19th century and thereafter, then how important is the presumed

presence of all natural dyes in adjudicating whether or not a piece is

"antique"? Presumably pieces woven within 15-20 years around the dye inflection

points cannot be reliably dated on that basis alone. A naive question from me is

"how much difference does it make to a rug's value based on dating of 1885 vs

1870 or 1865 vs. 1850?" It seems likely that two very similar pieces made at

exactly the same time (e.g. 1885) would be valued very differently if one had a

synthetic dye and the other was all natural, regardless of their overall

aesthetic quality and construction. Furthermore, it seems very likely that

experts would date the one with a synthetic dye as being "later" than the other,

without much evidence to support the theory.

Later inflection points

(early to mid 20th century) might be important for some pieces, but I doubt that

they very often factor much into the issue of paying an "antique

premium".

So I still think that if it has not already been done, then it

would be useful to novice rug buyers for someone to compile a "dating chart" or

"rules of thumb" that were specific to weaving type (e.g. Tekke torbas, chuvals,

main carpets; various Caucasian rug types, etc.), and included synthetic vs.

natural dyes as one of the criteria. That might also clarify when and how dye

assessments have a distinguishing value.

Rob's observation about rarity

is an interesting, if somewhat divergent issue. I suppose that a particular

premium is deserved for a unique beautiful rug, since a beautiful rug is likely

to be emulated by others. I suppose that there are many more unique "ugly" rugs

which are "one-of-a-kind", and for good reason! A former professor of mine

reminded me that "rare things happen all the

time"....

Cheers,

James.

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 05-26-2005 02:54 PM:

Hi James,

I forgot to mention that rarity ( which indeed isn't the

same as beautiness ) is most likely a clue for a rug with more age, as there are

just less remaining of them.

When studying the parameters ( e.g. the colors

) in such pieces, it gives insight in how a piece with more age will have

different parameters compared to the more usual ones, and in this thread : what

the colors look like in the pieces with more age, compared to pieces with lesser

age.

Best regards,

Rob.

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-26-2005 03:29 PM:

James -

Several points, although I think most of them have been made

above and you're not "hearing them."

First you say towards the end of you

most recent post:

"...So I still think that if it has not already been

done, then it would be useful to novice rug buyers for someone to compile a

"dating chart" or "rules of thumb" that were specific to weaving type (e.g.

Tekke torbas, chuvals, main carpets; various Caucasian rug types, etc.), and

included synthetic vs. natural dyes as one of the criteria. That might also

clarify when and how dye assessments have a distinguishing

value..."

Me:

The fact that something might useful to have does

not mean that it can be constructed. We've said repeatedly that estimates of

both age and dye character are made on the basis of multple criteria and

perspectives and that most of these judgments are conventional rather than

rooted on hard data.

Second you question Pinner's estimate of "possibly

before 1850... because of the dyes" because the data clearly suggest that

natural dyes were used to some extent in the third and fourth quarter of the

19th century and perhaps after that.

Such statements alway need to be

read primarily as indicating how old a given piece might be at the maximum. They

do not take on at all the possibility that rugs woven entirely with natural dyes

might well have been woven after the dates on which synthetics were initially

used. There are natural dye rugs with Sarouk designs and structure being woven

today in India (and other places as well) that will in one hundred years will be

very difficult to distinguish from those woven in NW Iran before the

1930s.

Now Pinner might well have been pointing to some additional

aspects of color with his indication. My torba has a distinctive apricot orange

in its guls. Pinner might well have known (by convention again) that this color

is associated with earlier Tekke weavings, but is not found in later ones (he

didn't say this, but it could have been part of what he meant; rug people, I

agree, tend to be a shade elliptical in their evaluative

indications).

Third, one reason that it might not be possible to build a

dye-age table, of the sort you would like, is that the move from natural dyes to

synthetic ones did not happen in a "cliff-like" mode.

Even where it

happened pretty quickly (Turkey, Central Asia, Tibet seemed to have gotten them

fast) there was likely a staggering of adoption. Many seem to feel that the dyes

in decorative rugs made in Iran were largely natural until about 1930, and in

some parts of SW Iran and among "Balouch" weavers it appears their nearly

exclusive use may have persisted even longer.

Someone may someday chart

the trade records that show when particular synthetic dyes were first marketed

in certain places (there are some such researches of various early colonial and

Ottoman records) but I know of no such studies relevant to your

question.

There is something oddly plaintive about your question of

what's the novice collector to do with regard to such things. It's a question we

all have about many aspects of life. It all seems more opaque and less

understandable than we might wish. It is, I agree, downright unfair.

But

that's the way it is.

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Steve Price on 05-26-2005 03:42 PM:

Hi James

I'd add to John's comments that not only didn't the adoption

of various synthetic dyes occur in synchrony, it was not even monotonic in

direction. A woman might very well have alternately woven with wool dyed with

all natural dyes and wool dyed with some synthetic dyes at various periods over

her weaving lifetime. It is completely plausible, even highly likely, that a

young woman in, say, 1865, wove a few pieces with a palette that included an

early synthetic dye and, 50 years later, wove some using only natural

dyes.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 05-26-2005 07:51 PM:

Hi all,

It seems to me that the question James is asking is quite

reasonable, basically: To what extent can knowledge of vegetal and synthetic

dyes contribute to the process of how a serious but novice collector makes good

judgements about the pieces under consideration for purchase ? And, how does one

acquire such knowledge ?

Unfortunately, as the varied responses show,

that is a fractal question: the answer has very similar characteristics at

various scales. The most detailed scale is that of the genre-specific collector,

for example: One who only collects pre-1865 Central Asian nomadic weavings and

whose reasons are tied to an interest in pre-Islamic shamanistic symbolism and

the manner in which it was still represented in woven tradition in the

post-Islamic, pre-commercialization era.

At that level of detail (or

rather, focus), dye specifics are tightly coupled to a few other well documented

features that help one classify what should be added to a collection and what

shouldn't. The knowledge and appreciation required to draw such conclusions is

acquired through a lot of study and over a considerable period of time. The age

of the piece, and its rarity, sets the price. The dyes just help get the age

pinned down.

But when applied to a broader area (for example) the

totality of Turkoman pile weavings, dye specifics are of less use because there

were some pieces produced with only vegetal dyes well into the early 20th

century. So the presence of vegetal dye, by itself, is insufficient to prove a

pre-1880 age. So someone interested in Turkoman goods in general, but less

concerned about age specifics, might be interested in judging vegetal dyes more

because they will be a component of the pricing "equation" for Turkoman goods

than because of academic collecting constraints.

And, finally, at my

own level of collecting, interest in the presence of vegetal dyes is largely

due to the recognition that their presence in 20th century items is the

exception rather than the rule (except for those vegetal dyed items made

expressly for commercial purposes like the Zollanvari gabbehs, DOBAG rugs, etc).

It's also a part of the pricing "equation". For one thing, I'm no expert on

dyes. I think I can spot vegetal dyes, but I'm certainly not egotistical

about it. And I look for them when selecting. But from a visual standpoint, I'm

more interested in the total "look" of the piece: anomalous attention to detail

on the part of the weaver, an attractive combination of colors and/or textures,

designs that are either visually pleasing or related to ancient motifs, an

ethnographic piece, etc. In short, an eclectic collector who has taken the time

to learn the specifics of a few genres, but who is not going to chair a

professorship as a result of the widespread appreciation of his

knowledge.

So, I guess that a message for the novice rug buyer is,

if you intend to drop big money on the table for a focused collection, restrain

yourself until you have taken the time to really understand the materials you're

interested in. Read a lot of books, visit a lot of dealers, handle a lot of

pieces. Then buy.

The utility of judging dyes is a highly contextual

issue. In certain genres, dye specifics can be extremely helpful. In others, dye

specifics have no value beyond adding a certain novelty to the piece, for

example: It was done with vegetal dyes well after the onset of the use of

synthetic dyes.

Here's an example, a Lakai Uzbek tent band. The dealer

bought it, while on a field trip in southern Uzbekistan, from a family of

nomads. He has given me the location of the yurt, the name of the family, and

the name of the woman (the man's mother) who made it in the mid-1920's. He was

told that she used vegetal dyes for the band. It has an additional strip with

tassles that is clearly an add-on and is embroidered with wool dyed with some

very bright synthetic dyes. The dyes are clear and fast. The Nikon Corporation

has generously contributed to the warmth of the red; I've done my best to get it

closer to what my eye sees.

The band (just a couple detail pics):

So, there you have it. If

he's right (and without a wet chemical test, who can prove anything ?) a lot of

nay-sayers have some crow to eat: it's a true Central Asian ethnographic nomadic

piece with vegetal dyes from the 20th century.

Vegetal or not, I like it.

And I like to keep in mind that, in these days of gaudy synthetic dyes, it is

still possible for the nomads of Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Central Asia to find,

buy, and wear clothes made of dull greens, liver reds, pale yellows, gray,

brown, and black. And they would if that was in their nature.

'nuff

said...

Regards,

(...I sure wish this thing had a spell check

function. HINT)

Chuck Wagner

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-26-2005 09:25 PM:

Hi Chuck,

Qashqaï women?

Yep, one can be lucky sometimes. I

trust you and I trust the dealer. But.....that man...I have my doubts. On the

other hand, the green shows up on my (newly calibrated) screen as a natural

green. But some synthetics can do the same trick. Even textile felt-tips can

deliver the same result.

But you're right.

It's a treat for our eyes and

that's what counts.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by James Blanchard on 05-27-2005 12:30 AM:

Thanks all.

I apologize if I am not "hearing" what is being said, but

I think that this thread confirms what I have sensed for a while. Steve's

proposal was that determining whether a rug has all natural dyes is important

because it contributes to the "dating" of a rug since an antique rug commands a

premium price. But it seems that beyond some basic guidelines about when and

where synthetic dyes were or were not used (which seem to be still in dispute),

the presence of natural or synthetic dyes basically adds to the "gestalt" of an

assessment, even for very experienced rug people.

I am sorry to sound

plaintive... I don't mean to. If I do it is not because I am a frustrated novice

collector (having never paid more than $1500, even for an "antique"), but

because I am a puzzled scientist. So as I learn more about rugs, I like to

understand how pieces of evidence about date and attribution cluster together in

a systematic way. I think that Chuck's point that stratifying by type of weaving

is a good start to a better understanding of how the evidence fits together, and

under what circumstances the types of dye should weigh most heavily in the

assessment of age. That was what I was trying to convey in my recent

posts.

Still, as with most pleasurable pursuits in life, I am perfectly

content to leave it mostly up to experience and "gestalt". After all, I am a

pretty "experienced" fly fisherman who couldn't tell you the Latin name for a

bug if you paid me.....

Cheers,

James.

Posted by David R.E. Hunt on 05-27-2005 01:40 AM:

Highly Specific,Hence Specialized Criteria

Hi James

You may not have noticed, but I have refrained from chiming

in on this discussion up untill now. For someone as color attribution challenged

as myself, not a bad idea, but now that the scope of the discussion has

broadened a bit maybe I should hazard an opinion or two

It seems to me that this

collecting and attribution stuff consists of a rather highly specific and

specialized body of knowledge, much of which is rather more at the arts than

science, and hence cannot be reduced to any simplified formula or set of

criteria.

Those criteria which might distinguish a natural Turkmen red

might not apply to a Turkish weaving or similar age or period, nor those of a

Caucasian weaving. Hence, attribution criteria are highly specialized, owning to

a list of factors the enumeration of which could constitute an entire salon in

itself, but just to mention a few could include types of dyestuffs available,

mordants, access to professionally dyed yarn, history of usage among a given

people along a given time frame, ect.. And this is just the

beginning.

Not to forget that the above criteria, in conjunction with a

knowledeg of and personal experience with both natural and artificial

dyes, will vary from tribe to tribe, from weaving group to country, among the

gamut of weavers. Highly specific and hence highly specialized. There are no

shortcuts, aside from hiring the reputable dealer to aid you in your selections.

But even then you can't understand them without this requisit background. Not to

suggest that there is anything wrong with just wanting a couple of cool looking

things to hang on the wall in the den

My suggestion is to pick a carpet, any carpet, and concentrate

upon learning as much about this type of weaving as you can. This Tekke torba is

as good an example as any, I guess. Determine the When, Where and Why of the

pieces described in the literature. If memory serves, one distinguishing

characteristic of the early torba is that of seeing the motive contained in the

guls repeated as the main element in the border, with emphasis upon the

singular. Some are wary of disclosing what they evidently regard as their

"proprietary" knowledge concerning the distinguishing characteristics of early

pieces. The internet is a great start, but books, aside from eyes on experience,

seem the way to get to rug connisseurship. And of course reading Turkotek

Dave

Posted by James Blanchard on 05-27-2005 02:40 AM:

Thanks, Dave.

I know I am out of my depth when it comes to antique rug

studies. My interest in this topic stems more from my feeling that rug

specialists can do better at documenting, summarizing and communicating their

knowledge. I appreciate that assessing and collecting old rugs is a highly

specialized field, and there are libraries full of books on the topic. Still it

seems that even experienced experts often disagree on attribution and age for a

particular piece. Is this because the field is so arcane and complex that it

defies better specification, or that there is a somewhat intractable mix of art,

science and commerce that conspires to muddy the waters? That is why I support

previous suggestions from Steve and others that we systematically assess the

reliability (i.e. reproducibility) of expert opinion on age and attribution. At

the very least, we could see how much consistency there is, and then further

examine the areas of inconsistency since those are likely the areas of greatest

interest.

Regarding the topic at hand.... It is evident that "natural

dyes" are usually considered as a broad proxy for greater age (even by

experienced and reputable dealers) when it seems obvious that this is an

over-simplification for the vast majority of rugs that were made more than

90-100 years ago.

So there is a definite price premium for natural dyes,

but how firm is the foundation for such a premium for most of the old rugs sold

these days?

I am still blissfully in the dark, in the den, enjoying my

rugs.

James.

Posted by Rob van Wieringen on 05-27-2005 07:05 AM:

Hi James,

You are quite right : commerce and muddy waters!

Two

befriended rugdealers are looking at the newest purchase of one of them. "How

old you think it is?" one asked to the other. "Well", he replied ," if you have

it its 19th. cent., but when I have it its 18th cent."

Considering

"natural colors" with ergo "greater age" is obvious an over-simplification.

I

think more important in this is what Michael Wendorf pointed to, earlier this

thread: Collecting traditional made items is also about collecting traditional

made colors. And I very agree with that.

Regards,

Rob

Posted by Steve Price on 05-27-2005 01:48 PM:

Hi Chuck

You expressed an aching for a spell checker in our software.

The software package we use is vBulletin. It doesn't include a spell

checker, but there are a couple of hacks that their user forum has for making

one. I have made a few hacks in our software, so the process itself doesn't

intimidate. We haven't made the spell check hack, though, for a couple of

reasons:

1. The vBulletin forum reports lots of problems with the spell check

hacks. I know enough to back up files before editing them, so I can reverse any

damage that a hack does, so this is only a minor issue.

2. Our forums are on

pretty unusual topics, and the vocabulary includes words that we use often, but

that won't be in a spell check's dictionary. Words like torba, juval, kilim,

cicim, Shahsevan, Yuruk, Karabagh, Shirvan, etc., etc., etc. will make the spell

check routine stop and ask what you want to do about it every time it gets to

one. I think this will be more of a nuisance than a

convenience.

Regards

Steve Price

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-27-2005 02:10 PM:

Hi Chuck

Isn’t simpler to write first your text in MS Word – or any

other word-processor with a spell-checker – then copy and paste it in Turkotek?

That’s what I do.

Regards,

Filiberto

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 05-27-2005 02:53 PM:

Hi all,

First: No, Vincent, not Qashqai although they also dress in

equally colorful clothing. These folks are Kurds from west Azerbaijian province

in Iran. Also, photo credit to N. Kasrain in "Our Homeland Iran", not me. I have

two books with dozens of images of contemporary Persian nomads. My wife bought

them in Esfahan. If you like, I can scan a few more photos & post

them.

As for using MS Word, yes, that's probably what I should do. But

first I have to develop the self discipline required to REMEMBER to use MS Word

(or WordPad). It's so much easier to be impulsive...

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by Filiberto Boncompagni on 05-27-2005 03:15 PM:

Hi Chuck,

Third girl from left looked familiar  : same as Jon Thompson's “Carpets from the

Tents, etc….” page 86. There she has the same dress, but she wears the purple

apron of the second woman on your scan.

: same as Jon Thompson's “Carpets from the

Tents, etc….” page 86. There she has the same dress, but she wears the purple

apron of the second woman on your scan.

Regards,

Filberto

(if

someone doesn’t believe it, I can post a scan  )

)

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-27-2005 09:08 PM:

Ah,

Yes, she looks familiar.

If I ever have a painting to restore,

your my kind of guy......eyes for detail.

"They" all visit the same "nomadic"

group!

It's like tourists asking who wears those darn wooden shoes in the

Netherlands........... "Nobody ......but if you pay, we'll dress up for the

picture"! And...all wooden shoes are handmade.

Best

regards.

Vincent

Posted by Chuck Wagner on 05-28-2005 10:42 AM:

Ah Vincent.. always the skeptic.

So, here's a URL with quite a few

images that you will enjoy browsing. For what it's worth, it is my understanding

that it is rather common for the nomads to "dress up" a little while they are

actually migrating. Once they settle in, the work clothes come out.

But

note that in these images, relatively few women are not wearing some sort

of colorful clothing:

http://www.irib.ir/Ouriran/CULTURE/nomads/htmls/en/Index.htm

How sad, no more wooden shoes in ethnographic use. So much for my wooden

clothing collection...

Regards,

Chuck

__________________

Chuck

Wagner

Posted by R. John Howe on 05-28-2005 08:47 PM:

Dear folks -

I just typed "hand carved Dutch wooden shoes" into an

eBay search and here is what comes up.

http://search.ebay.com/Hand-carved-Dutch-wooden-shoes_W0QQfkrZ1QQfromZR8

Maybe

Vincent can speculate about whether any of them look "real."

I do

encounter quite frequently in antique malls here wooden shoes labelled as Dutch

and claimed to have been hand carved.

Is there a movement to keep Dutch

"culture" alive in this way?

Regards,

R. John Howe

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-28-2005 09:45 PM:

Hi John,

I can't tell because I don't know.

Maybe there are

handmade wooden shoes. But most are being cranked out in mass production for our

Japanese and American guests . But...all are handpainted!

And yes, there

maybe some Batavians in the Dutch wilderness that keep this culture

alive.

But wooden shoes with holes in them for display and to tie them

together? No, my wooden shoes didn't have any holes, I could walk through mud,

cow- and horse manure etc. No problem.

But mine came from Sweden! No

holes.

Best regards,

Vincent

Posted by Patrick Weiler on 05-29-2005 09:24 PM:

New technique?

Chuck,

The photographs in the link you provided are great.

As

for determining natural dyes, a new technique has recently been developed.

An article in Science News describes a way to determine the source plants

from which the dyes were made. The article does not say what results would be

found if synthetic dyes were used in a weaving, but they would probably be

different than the results from naturally dyed materials.

Here is a copy of

the article:

Color Trails: Natural dyes in historic textiles get a closer

look

Alexandra Goho

Chemists have developed a way to extract

natural dyes from ancient textiles while preserving the unique chemical

characteristics of each dye. The technique enables the researchers to then

identify the plant species from which the colorants came.

Determining

the source of dyes could open a new window on how ancient people used natural

resources, says chemist Richard Laursen of Boston University. What's more, since

plants grow within set geographic ranges, characterizing natural dyes could help

archaeologists trace the movements of tribes or determine trade relations

between distant communities.

Laursen and his colleague Xian Zhang, also

of Boston University, used their new chemical method to analyze yellow plant

dyes called flavonoids. Many dye flavonoids have attached sugar molecules that

are specific to each plant.

Traditionally, textile manufacturers have

used a substance known as a mordant to bind dye compounds to fibers. "It's a

practice that's been used for thousands of years," says Laursen. First, the

textile is soaked in a solution containing the mordant, which, in most cases, is

an aluminum salt. Aluminum ions penetrate the fabric's fibers, and then, in a

second bath, dye molecules bind to the ions. The result is a colored textile

that holds on to its dye.

To extract the natural dyes from historical

textiles for analysis, researchers have typically relied on harsh chemicals,

such as hydrochloric acid, to separate the dye from the mordant. However, this

process also strips away the flavonoids' plant-identifying sugar molecules. "You

lose a lot of the information this way," says Laursen.

As they report in

the April 1 Analytical Chemistry, he and Zhang extracted yellow dyes from test

fabrics using different, milder reagents: ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA)

and formic acid. The Boston researchers tested their method on silk fibers that

they had dyed with flavonoids from different natural sources, such as

pagoda-tree buds from a local arboretum and onions from a supermarket.

Laursen and Zhang soaked their dyed silk samples in hydrochloric acid,

EDTA, or formic acid, extracted the flavonoids, and chemically characterized the

compounds. They found that the treatment in strong acid stripped away the

distinguishing sugars of the flavonoid dyes, making all of the dyes appear

chemically the same. The milder reagents, however, preserved the sugar

signatures of the flavonoids' sources.

The researchers also tested their

method on textile fibers from a 1,000-year-old mummy in Peru. They found a new

type of yellow dye, a flavonoid sulfate, that was previously unknown to

archaeologists. "You wouldn't see it using the traditional methods," says

Laursen. It turns out, he adds, that a certain group of plants in Peru and

Argentina are rich in flavonoid sulfates and that there's a long tradition of

using these plants for dyeing textiles.

Irene Good, a specialist in

ancient textiles at Harvard University, says the new dye-identifying technique

"is extremely important and very promising." In addition to pegging the specific

plants used to make dyes, the method could reveal how natural dyes were

processed by ancient peopleÑfor example, whether they dried plants or used them

fresh, she says.

References:

Zhang, X., and R. A. Laursen. 2005.

Development of mild extraction methods for the analysis of natural dyes in

textiles of historical interest using LC-diode array detector-MS. Analytical

Chemistry 77(April 1):2022-2025. Abstract available at http://pubs.acs.org/cgi-bin/abstract.cgi/ancham/

2005/77/i07/abs/ac048380k.html.

Further Readings:

Parsell, D. 2004. Remnants of the past. Science

News 166(Dec. 11):376-377. Available at http://www.sciencenews.org/articles/20041211/bob8.asp.

Sources:

Richard Laursen

Department of Chemistry

Boston

University

Boston, MA 02215

Irene Good

Peabody Museum

Harvard

University

11 Divinity Avenue

Cambridge, MA 02138

From Science

News,ÊVol. 167, No. 15,ÊAprilÊ9,Ê2005, p. 230.

Patrick Weiler

Posted by Vincent Keers on 05-30-2005 12:08 PM:

Hi,

The researchers also tested their method on

textile fibers from a 1,000-year-old mummy in Peru. They found a new type of

yellow dye, a flavonoid sulfate, that was previously unknown to archaeologists.

"You wouldn't see it using the traditional methods," says Laursen. It turns out,

he adds, that a certain group of plants in Peru and Argentina are rich in

flavonoid sulfates and that there's a long tradition of using these plants for

dyeing textiles.

But this doesn't mean the sugars are from a plant

directly. I can't see how the Indians extracted the alum from the earth. Maybe

they buried the fibers in the earth (bauxite) or washed the fibers in the rivers

and lakes (red) and the earth and water contained all kinds of different plant

spores and remains?

whether they dried plants or used

them fresh, she says.

I don't understand this. Do the sugar molecules

disappear if the plants are dried?

And, if I eat onions, do the onions

leaf traces of sugar molecules in my urine! If so, urine is an old mordant

and....yellow!

But Patrick, I'll start right away, eating onions. And

I'll send in my urine for urinalysis.

Thanks for the address

Best regards,

Vincent

In any case the meaning is still the

same: the assumption that a rug was made without any intervention and material

from our industrialized world – like synthetic colors and machine-spun wool.

In any case the meaning is still the

same: the assumption that a rug was made without any intervention and material

from our industrialized world – like synthetic colors and machine-spun wool.

: same as Jon Thompson's “Carpets from the

Tents, etc….” page 86. There she has the same dress, but she wears the purple

apron of the second woman on your scan.

: same as Jon Thompson's “Carpets from the

Tents, etc….” page 86. There she has the same dress, but she wears the purple

apron of the second woman on your scan.  )

)