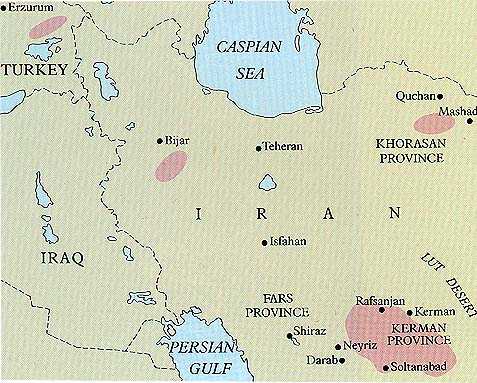

Map

Showing Primary Afshar Territories From J. Opie, Tribal

Rugs 212 (1992)

Map

Showing Primary Afshar Territories From J. Opie, Tribal

Rugs 212 (1992)Editor's Note: The following article is an account of Parvis Tanavoli's presentation to the New England Rug Society. The article appeared in the November issue of The New England Rug Society Newsletter. Thanks to Jim Adelson and Yon Bard for permission to publish it here.

On November 7th, Parviz Tanavoli explored Afshar weaving, one of his many areas of expertise, for the benefit of the New England Rug Society members in attendance. For those who don't know his work, his knowledge extends to other types of art, particularly sculpture, and many areas of Iranian weaving.

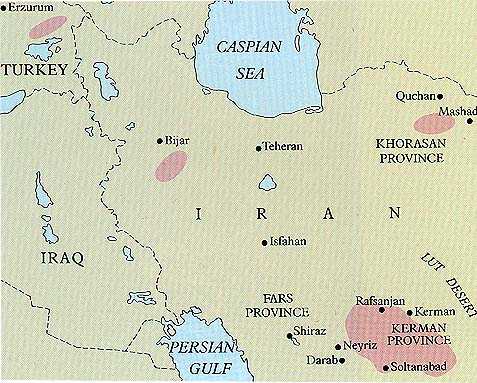

According to Tanavoli, the Afshar are perhaps the oldest of the Turkic tribes. They are scattered now into most areas around Iran, with the largest concentration in western Kerman province. Their lifestyle has remained largely the same for 1000 years and still includes nomadic migration complete with traveling teachers for the children. Tanavolia observed that "women do all the work; men sit around and smoke." Unfortunately, the Afshar, who as a people were once the elite of the Kerman province, have been becoming poorer and poorer over the past century.

Map

Showing Primary Afshar Territories From J. Opie, Tribal

Rugs 212 (1992)

Map

Showing Primary Afshar Territories From J. Opie, Tribal

Rugs 212 (1992)

Study of the group has proved frustrating. Distinguishing some of the sub-groups is difficult, and there has been much intermarriage between the Afshar and other adjacent people. This may be one of the reasons that so many designs can be found.

Tanavoli started his examination of Afshar designs with tree carpets, pointing out that the design may have been copied from Kerman carpets or tiles. The tree design was very popular, and Parviz showed examples of its use in housing and even in a coffin. Some of the other popular designs were drawn from more distant sources, including medallion carpets with a possible Northwestern Iranian origin, Turkmen-influenced designs, and the 'cabbage' or European rose design. All the women weave either flatweave or pile pieces from memory - no cartoons.

center>4'1"x5'8" Afshar Rug: Opie, Plate 12.8

center>4'1"x5'8" Afshar Rug: Opie, Plate 12.8

The structure of Afshar weaving similarly shows variety. Most pieces use semi-depressed warps, symmetrical knotting, and double wefting. Other pieces are single-wefted, and some also use a special knot that is neither the standard symmetric nor asymmetric knot. There are pieces with warp and weft of either wool or cotton. Contrary to claims for some weaving groups (e.g., Bijars), there is no evidence that either wool or cotton is always older. In fact, some of the oldest examples have cotton foundations. There are certain structural characteristics that are related to age: as a general rule, 19th-century carpets have flatwoven ends, while 20th-century pieces do not. The presence of other neighboring groups and intermarriage complicates the structural analysis, since these adjacent or intermixed groups make different products, with much denser weave, heavily depressed warps, and thicker, greasier wool. [Click here for editor's note on structure]

The slides that accompanied the presentation illustrated a wide range of objects. In addition to more typical types of rugs, which frequently have a squarish format, Tanavoli showed small 'throne' carpets, designed to be laid on top of other carpets, for Shahs to sit on. The Afshar are well-known for their sofreh, a flat-woven cloth for making, eating, and storing bread. They also weave large and small bags, including khorjin, salt bags, and tobacco bags.

center>Afshar Bagface or Sofreh, Plate 273, Atlantic

CollectionsCollection of J. A. Smith

center>Afshar Bagface or Sofreh, Plate 273, Atlantic

CollectionsCollection of J. A. Smith

The group wove primarily for internal consumption, but during the short period from the late 1920s to the second World War, merchants descended upon them and both production and export expanded dramatically. Weavings of that period exhibit chemical dyes, alien wools, and a general hurriedness of production. Other than those two decades, Afshar weaving has been somewhat less influenced by commercial interests than those of other groups.

In addition to slides, Tanavoli brought examples (fresh from the walls of his NERS hosts!). A number of NERS members brought their own pieces, too, adding to the live inventory. Many thanks to Parviz Tanavoli for his first-hand observations and research insights into the Afshar!

According to Opie, "Woolen warps and wefts predominate in Afshar work until cotton was adopted in the 1930s. Wool warps are almost invariably ivory in color, though minor admixtures of darker wool or goat hair are occasionally found. . . . Wefts are commonly dyed red, sometimes with a decidedly orange tinge which distinguishes them from Khamseh work."

To return to the text, click here.

To comment on this article e-mail Steve Price.

![]()