The Turkmen Engsi:

Doorway to Paradise

The Turkmen engsi served a complicated collection of purposes. They were physical accoutrement for the purposes of prayer or invocations, to support the spirit's connection between the spheres, as well as a protection against harmful influences. The various bird images on the engsi assisted in leading the spirits to the upper world. It was also the responsibility of the engsi to accompany the souls of the deceased ancestors on the journey from the world of the living to the world of the dead. For that reason we have entitled this exhibition:

Engsi - Doorway to Paradise

We can also assume that they were placed on the doors of yurts on important occasions, such as weddings, deaths, or receptions for important visitors, and at other times, hung inside the tent as icons.

Peter Hoffmeister, from the catalog introduction

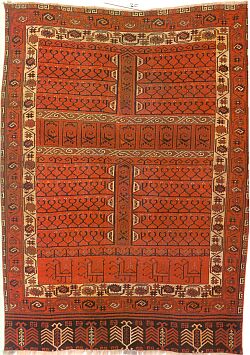

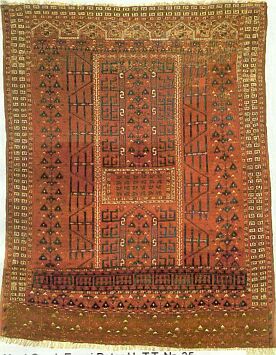

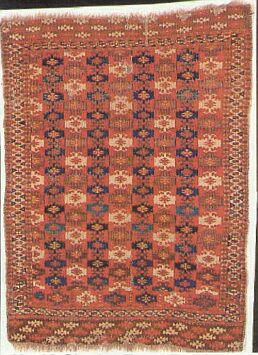

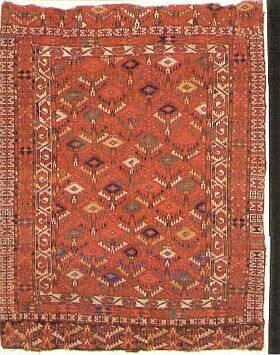

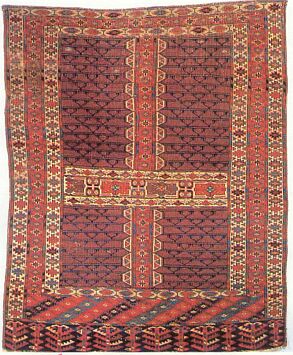

1. Salor Engsi, Type A

(Note: This is not an image of the Salor, Type A piece that will appear in the exhibition. That image went directly to Murray Eiland without my obtaining a copy. This is simply a marker image for convenience.)

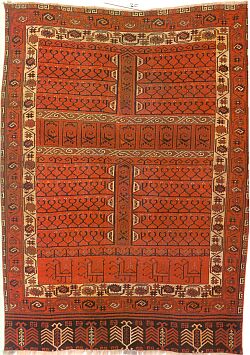

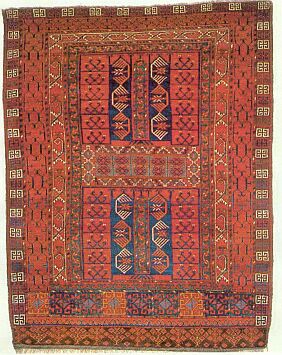

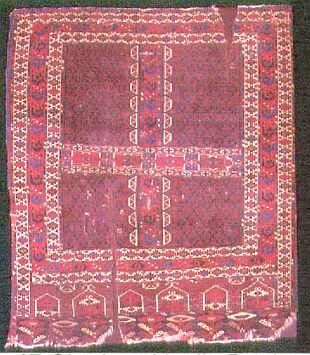

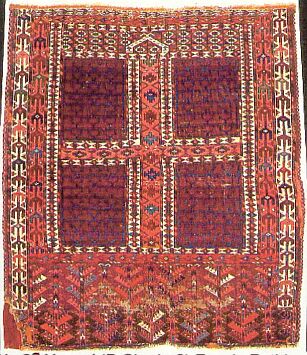

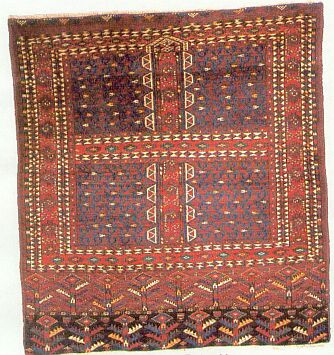

2. Salor Engsi, Type B

"Everybody is intrigued to know what all the different designs and motifs found in oriental carpets mean and it would be a pleasure for me to be able to give some examples of different designs together with a statement of their meaning - a sort of A equals B explanation. Unfortunately, symbolism is no amenable to this kind of treatment.

"The idea of the symbolic is not easy to grasp, especially for the western mentality, which favors the formal and literal approach and finds difficulty with the metaphorical and allegorical. The literal approach can demolish the metaphorical, make it look ridiculous and at the same time miss its message entirely. It reduces the symbol to a sign. If the motif has a single generally accpeted 'meaning,' then in common parlance it becomes a sign - this stands for that in a one to one relationship, as in musical and mathematical notation, traffic lights, road signs, the printed word and so on. The symbol, in the sense we wish to use it, cannot be substituted for by a word; rather it addresses in a language peculiar to itself a part of the mind which does not use words. Were it not so there would be no value in using any form of communication other than words... "

The information can be a feeling, an inspiration, or a evocation, a reminder, a wish, a prayer, a longing, an offering or any or none of these things…"

Jon Thompson, quoted by Peter Hoffmeister in the catalog introduction

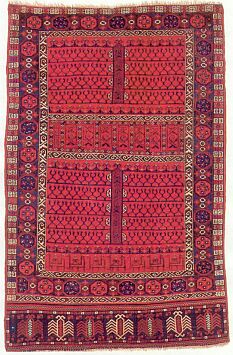

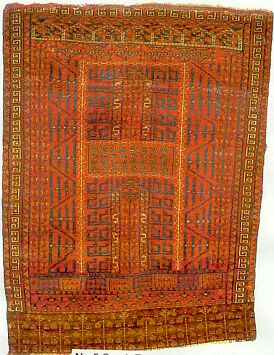

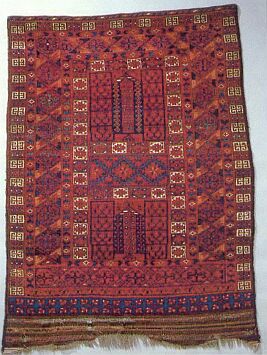

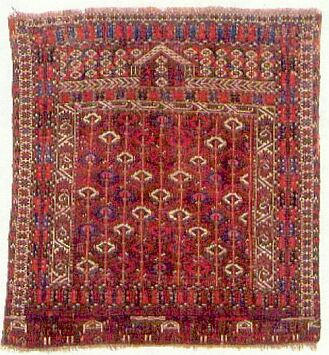

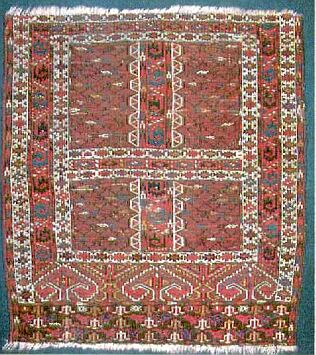

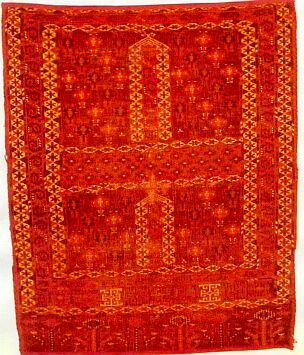

3. Saryk Engsi

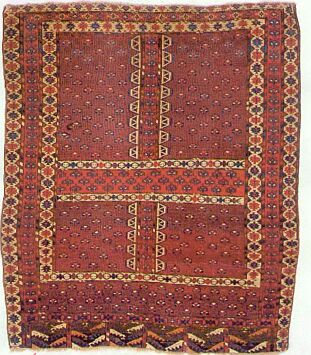

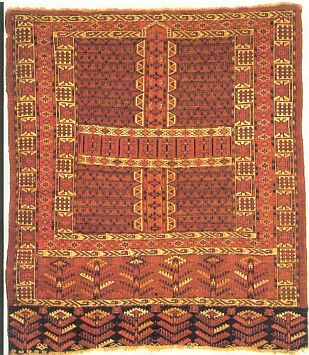

4. Saryk Engsi

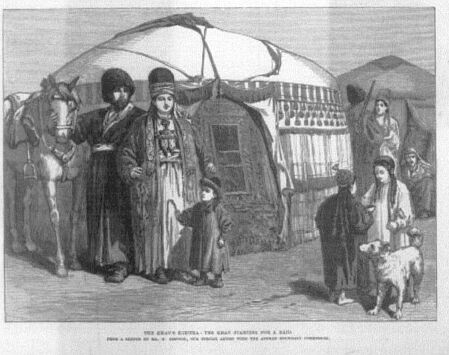

Despite the frequent indication in the recent rug literature that the engsi was a door rug, there is surprisingly little evidence of such use.

Here is one item discovered by Neil Moran. For some time this has been seen as the only picture we have of an engsi in use. It is a drawing of a Saryk engsi on the door opening of a trellis tent, made near Pende, in 1885, by an artist for The London Illustrated News who was covering the Afghan Boundary Commission.

This is a drawing, not a photo, and is in some respects an instance of "orientalism" in that the scene is acknowledged by the artist to be to some extent "composed" of human images seen elsewhere, but the picture is seen by rug scholars as authentic in its depiction of the engsi "in use"on a Saryk tent door opening. Here is the text that referred to this drawing:

"…We have already described the felt tents of the Turkomans, called by the Russian's 'kibitkas.' At Penjeh, where the Sarik Turkomans form a large community, our Artist saw an ornamental residence of that kind. The roof of the kibitka in this case, it will be seen, is a dome; in this particular the form varies in the different localities. The sides here are ornamented on the outside with drapery, as well as color fringes and tassels. These are very tastefully arranged around the door, the door itself being formed by a beautiful carpet. 'I managed,' he says, 'to get sketches at Penjdeh of some of the women and children, which I have introduced, and have made into the subject of 'Departing for a Raid.' The Khan, or chief, has his horse ready to mount; one arm caresses the horse on which his life may depend during the raid, while the other fondly embraces his wife. She, in the anxiety of the moment, turns to her child, who, with whip in hand, evidently wishes to ride his father's horse. At a kibitka behind, another Turkoman is bidding goodbye to someone dear to him. The dog looks as if even he knows what is going on, and is ready to start. The woman's dress is peculiar; she wears a high hat, in shape like a Papal tiara, and her person is covered with large silver ornaments. The one on her breast is for holding charms."

Robert Putnam has argued that the proportions of the carpet in this drawing are different from the engsis we have. He notes "…The width to length ratio is roughly 1:3.5 while a typical Saryk engsi is much squarer, with a width to length ratio of no more than 1:1.5 (1:1.3 in the later pieces).

Hali, 94, p. 59

A year earlier, an officer with the Afghan Boundary Commission reported.

"Everyone here has been busy, and I regret to report that the officers, without an exception, have by their conduct during the last day or so, rendered themselves liable to be called 'carpet knaves.' The Turkomen young ladies have a deft way of working a particularly fine kind of carpet and some of the finest of these serve as doors of the kibitkas; they are hung like a curtain. There has been quite a run on these carpets or 'doors' here. Prices have gone up to fabulous sums. Our winter quarters are to be kibitkas, and everyone wants a carpet or two and a 'door' as well. It looks as if some of our party are going to have very large kibitkas, a kibitka say with a half a dozen doors at least. The largest and finest kibitka I have yet seen in Penjdeh had only one door. This was a very handsome residence. It was hung round with fringes and tassels and the door was covered with a very beautiful carpet. It had a bloom on it like a peach. Some suggested that it would be the Lord Mayor's residence, and it was at once christened The Mansion House.

"At first new carpets were brought for sale but someone brought an old one beautifully toned down from the time it had hung on a door.

"This was bought up at a high figure and soon as the value of old rugs was discovered there was a rush on the kibitkas, and every ragged old article was brought to market. This led to some amusing scenes. One of our people bought a carpet from an old man, and had paid the money, when the wife appeared. She seemed angry, and seizing the piece of carpet carried it off triumphantly and hung it up in its place over the door of the kibitka. The old man looked rather forlorn, for he had to hand back the silver coins."

Hali, 92, p. 71

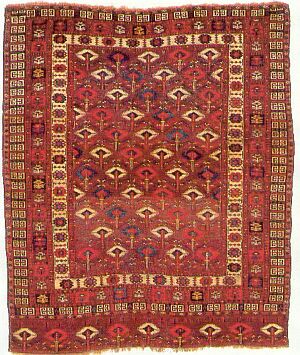

5. Saryk Engsi

6. Tekke Engsi

"Traditional folk culture has an intriguing universal feature: whatever is produced has to be decorated; and if there is an ornament it usually has some magic meaning of this or that kind. In other words, function-ornament and magic are melted together in traditional culture and it is impossible to understand one without the other."

Elena Tzareva, from the catalog introduction

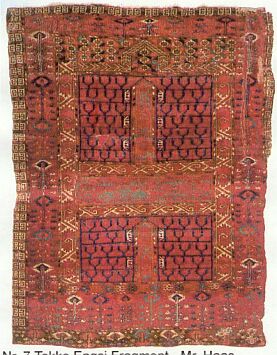

7. Tekke Engsi Fragment

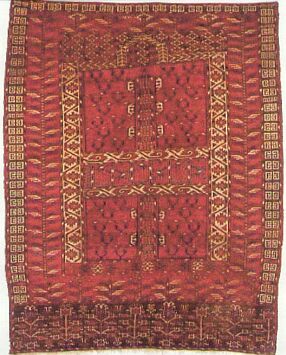

8. Tekke Engsi

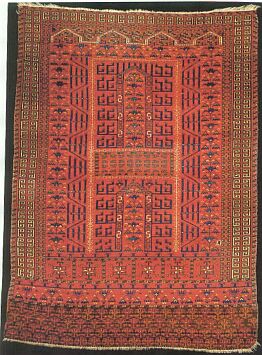

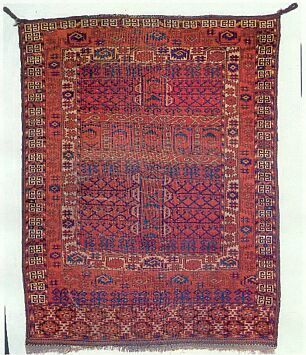

9. Ersari Engsi

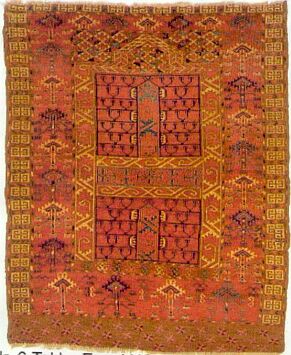

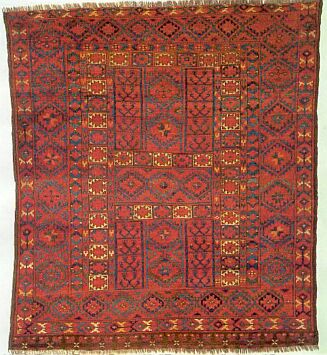

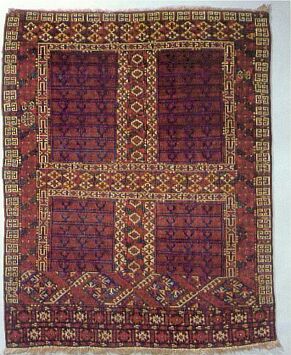

The key to understanding the engsi lies in its composition. This is clearly observed in exhibition number 10. The bottom panel - elem - is darkly colored, as they are in almost all engsis. The main field contains the typical cross design. This design can also be found on the wooden doors of the yurts of almost all Central Asian nomads. It can be hypothesized that it that it represents the four points of the compass. The vertical axis of the midfield sometimes contains a design of the Tree of Life, the outer sections continuing the tree motif with branches and birds. Similar designs can be found in nearly all engsis, although rarely with such clarity. The Tree of Life stands in the world of the living and connects it with a heaven, which we can only imagine. In many engsis we find gable forms on the upper part with kotchaks or small cottages with kotchaks on the gables. Since the dawn of Man, these have been a symbol of the "Upper World." The kotchak design developed from the symbol for the moon and stands for the process of regeneration, for the continual renewal of life.

Peter Hoffmeister, from the catalog introduction

10. Ersari Engsi

11. Ersari Engsi

12. Ersari Engsi

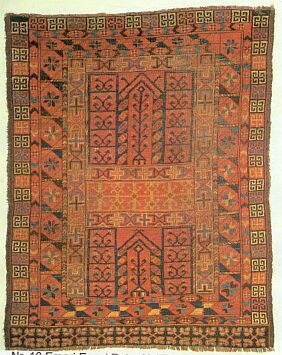

13. Ersari Engsi

14. Ersari Engsi

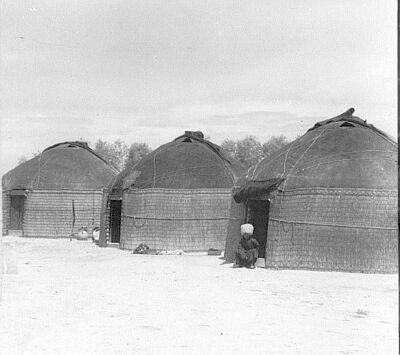

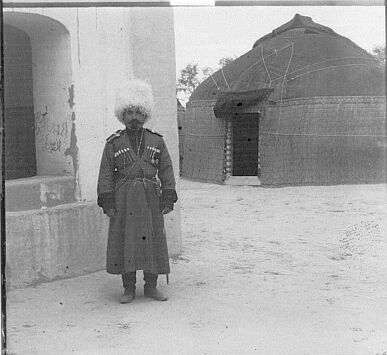

In a recent Turkotek discussion on the internet, Robert Alimi, of the New England Rug Society, called attention to some photos in the Prokudin-Gorskii Collection from the Library of Congress. These photos, many of which are in color, where taken by a Russian nobleman in the early 1900s. Some of us had seen these photos, but not with Mr. Alimi's sharp eyes.

It seems possible that the rug on this trellis tent door is pile and that it may have a "hatchli" design. It may be the only known photograph of a Turkmen engsi in use.

15. Kysyl Ayak Engsi

16. Chodor Engsi

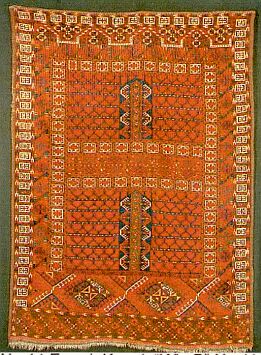

17. Yomut Group Engsi

18. Arabachi Engsi

19. Yomut Tribes (P-Chodor?) Engsi

20. Yomut (P-Chodor?) Engsi

21. Yomut (P-Chodor?) Engsi

22. Yomut Engsi

23. Yomut Tribes Engsi

24. Yomut Tribes Engsi

25. Yomut Tribes Engsi

26. Chodor? Engsi

27. Yomut Engsi

"…how are we to approach such objects? Well, I suggest you look at them with just two questions in mind: which are the ones which convey their maker's passion most obviously, with relative ease? And which are those that seem most packed full of meaning? - never mind just what the meaning might have been. Have an unusual experience.

Simon Crosby, UK, from the catalog introduction