|

|

|

|

#1 |

|

Members

Join Date: Oct 2009

Posts: 153

|

Hi all,

The simplicity of its motifs has made this small square rug (*) one of my favorites among Renaissance studio props. A single 8-branches « Rub el Hizb» star hovering over a beautiful red background and a forceful & original border. No «horror vacui» here! Pity that della Francesca did not show a little bit more of it. FIG 1 & 2   P. della Francesca. Virgin and Child with Federigo de Montefeltro. 1472. Brera. Milano. The knot density seems quite high despite the simple pattern. The «Rub el Hizb» motif makes an Islamic origin of the rug highly likely. The analogy with the square nineteenth-century Moroccan flag below is quite interesting. FIG 3.  (*) The picture definition does not allow to be sure that this is indeed a rug, rather than another type of textile, a velvet for example. However, it is generally assumed to be a rug in the literature. Regards Pierre |

|

|

|

|

|

#2 |

|

Administrator

Join Date: May 2008

Location: Cyprus

Posts: 194

|

Well, Pierre, there is a good commentary about this painting and its rug in the book of Luca Emilio Brancati “I tappeti dei pittori”. Here it is, with related scans:

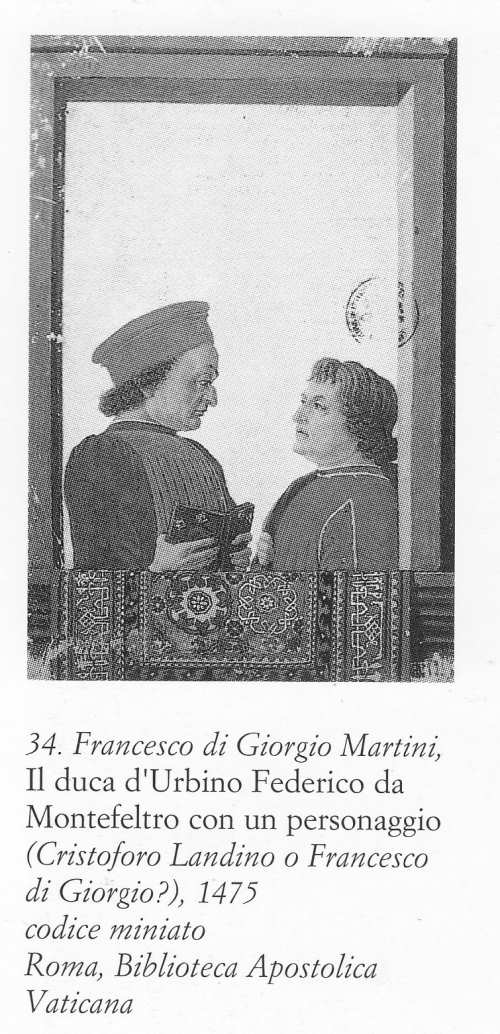

“The balanced composition and iconography present in this painting, which has led to numerous questions on its interpretation, leads one to believe that the presence of the rug is not casual but is the direct wish of either the artist or the client. Leaving aside possible comparisons for which there is no longer any trace, the main purpose of the rug here is to frame and raise the sacred space occupied by the Madonna and Child. This space is different and more privileged to that occupied by the angels, the saints standing barefoot on the stone floor, and by the kneeling offerer. It seems to capture an echo between the geometric rigour of the carpet and the figure of the monumental, aloof and indecipherable Madonna, similar in many respects to Oriental statuary. As with the smallest details of the scene, the finest details of the rug are also clearly depicted. The folds and undulations of the border provide depth to the material. The pile is represented with a 'salt and pepper' effect to portray typical colour variations in the wool. Other small technical details convince the viewer of the nature of this textile: the presence of a fringe made of thin white yarn that comes from the red ends to the left, the thin line that defines the selvage, and the criss-cross painted on the back of the rug to convey the idea of a warp and weft weave. A digital reconstruction of the rug (fig.32) has  (Fig.32) shown that it is almost square and that, despite being covered by the Virginis mantle, the star medallion at the centre consists of the typical star and bar design format which is common on the so-called 'large pattern Holbeins' or 'wheel' carpets (fig. 35). In addition, Piero della Francesca's scrupulous perspective of the rug can now be seen clearly: after having used computer graphics to eliminate any effects of perspective on the visible part of the rug, no deformations as such were registered other than a logical loss in the definition of the drawing. This highlights a quality that is in fact Piero's stylistic signature, and which leaves no doubt about the careful rendition of a real carpet for which there are none in existence today that might conceivably be used for comparison. Critics have not always agreed on the attribution of the rug. First, Julius Lessing, talking about the border motif noted that the representation "does not show the material clearly and its oriental provenance is uncertain" (Venetian school: 1879, p. 21 ,Pl. 28 E). Wilhelm von Bode and Ernst Kühnel believed this rug to be of Anatolian provenance, but together with Foppa's fresco (Pl. no. 5) he quoted them as being examples that were altered by artists for figurative requirements (1914, p.138); a consideration which remained unchallenged in Charles Grant Ellis's translation of the same work (Bode- Kühnel, 1984, p. l6). More generically, Gustave Soulier included it among carpets of "geometric combination" (1924, p.208), whereas Michele Campana, in the list published for his 1945 work, involuntarily provides us with two conflicting attibutions: on the one hand, quoting Bode, he listed the Brera altarpiece, correctly attibuted to Piero, as a rug from Asia Minor (1945, p. 172) whereas a few pages previously, with the old attribution to Fra' Carnevale da Urbino, he talks of a "superb Damascene or Syrian rug" with an emphasis sug- gesting that this was to be considered his opinion (ibidem, p.167). Finally, more recently, Ian Bennett placed this carpet among the so-called 'large pattern Holbeins', thus suggesting Anatolian provenance (1977 , p.99). Although there are clearly features that are common to rugs from the eastern Mediterranean basin, mainly Mamluks and Anatolians, we also find various aspects which distance us from that area: a single star and cross border, an uncommon format, a yellow lily with little stylisation (unusual for middle-eastern rugs) that can be found in the triangular points of the star medallion. Surviving examples of 'large pattern Holbein' rugs do not provide us with satisfactory comparisons. But some originals of the thirteenth century and various examples featured in oriental miniatures of the Timurid epoch suggest something different. Comparing the border motifs with rugs from the Seljukid period (thirteenth century) found in mosques at Konya and Beyshir (Istanbul, Türk ve Islam Eserleri Müzesi, inv. nos. 655, fig.37, 688, 1034; Vakiflar, inv. n. A-344, fig. 36)  (Fig. 35, 36 and 37) we find there are several common denominators: the succession of eight-pointed stars, the rhythmic feel, the simple composition, and the deep saturated colours. Furthermore, a comparison with decorative motifs from carpets in Timurid miniatures shows a perfect adherence to the star and cross sequence in the border of our rug, with the grid defined by Amy Briggs as being of type II (Briggs, 1940,p.23;here fig.22). One might even suggest that Piero's rug represents an evolutionary mid-way point between the Seljukid and Ottoman 'Holbein', or possibly Timurid, carpets. It was certainly a precious piece in Montefeltro's time which is why it was so highly regarded. With documents to confirm that Piero was in Urbino during these years, and assuming that Federico de Montefeltro was the client as shown by the painting, one might suppose that the artist had a chance to see the carpet at his court. Perhaps the duke had a penchant for rugs. In the almost coeval miniature on parchment by Francesco di Giorgio Martini for the Disputationem Camaldulensium by Cristoforo Landino (1475; Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, doc. Urb. Zat. 508) the duke is shown in profile as usual, talking with a person (Landino) at a window for which the only decoration is a 'small pattern Holbein' or 'wheel' rug (fig. 34).”  (Fig. 34) Regards, Filiberto |

|

|

|

|

|

#3 |

|

Members

Join Date: Oct 2009

Posts: 153

|

Hi Filiberto,

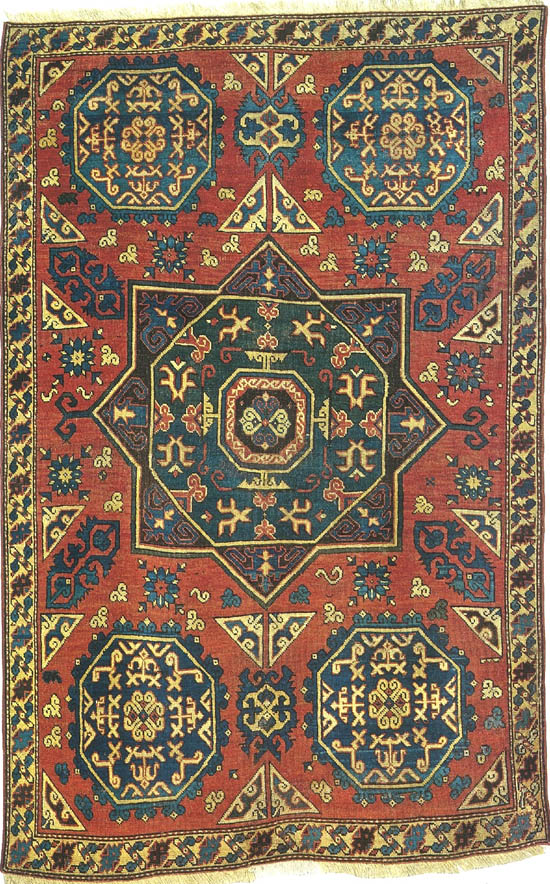

Thanks a lot for sharing with us Brancati’s informations and the highly interesting computer reconstruction of the rug. I like the little stylized lilies included in the eight Rub el Hizb points. There is a, probably fortuitous, analogy with the «kochak» motif of Salor rugs. The following sixteenth century extant anatolian rug is the closest thing to della Francesca’s carpet which I could dig out so far. Sure, the red field is more crowded, but it features the bold eight-pointed star with the eight lilies (?) and also the large octagon inside the star.  FIG. Western Anatolia, sixteenth century, 212x135, Heinrich Kirchheim, Orient Stars, page 237. Oh, and several extant fifteenth- and sixteenth century Mamluk rugs also feature a large Rub el Hizb medallion. However, the esthetics of della Francesca’s rug and of Mamluk carpets (very low contrast, overcrowded field etc..) are really as far apart as can be. IMHO a common origin is not credible. Best regards Pierre |

|

|

|

|

| Thread Tools | |

| Display Modes | |

|

|